[music]

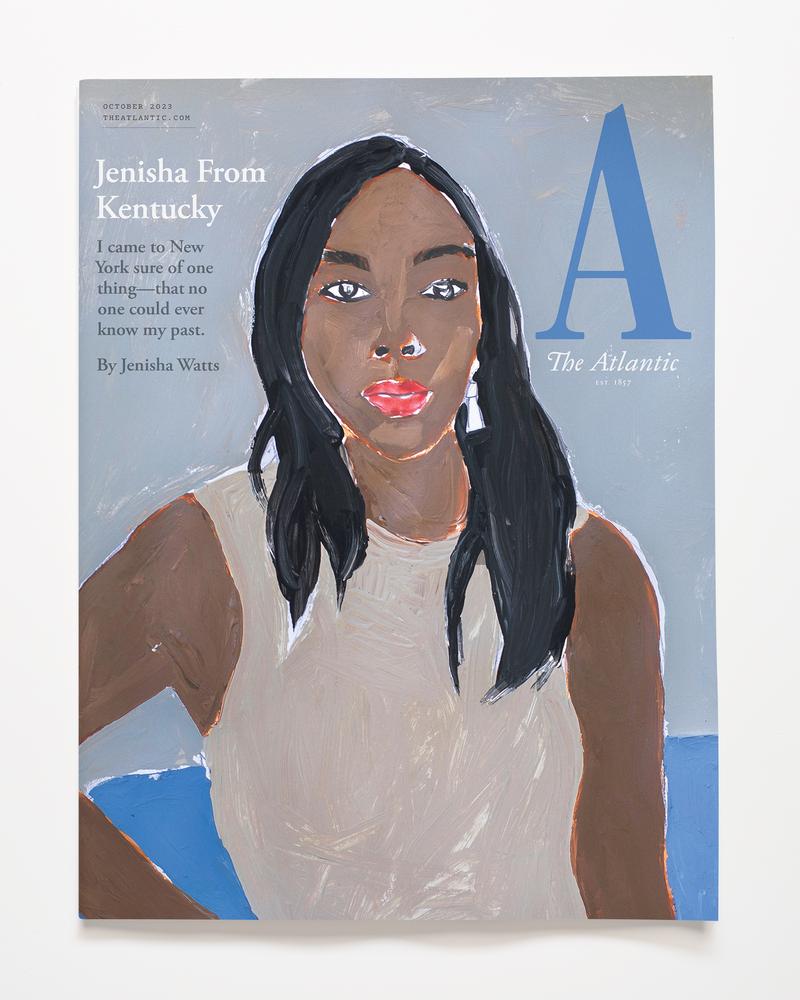

Arun Venugopal: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Arun Venugopal from the WNYC and Gothamist Newsroom. Now, we're going to wrap up today's show with a story of perseverance. Our guest joining us in a moment is Jenisha Watts. She's a senior editor for The Atlantic, but her background is quite different from others in her field. In her latest piece titled I Never Called Her Momma, Jenisha Watts shares a story of her childhood for the first time as well as her journey to her current life, and now, she brings her story to us. Jenisha, welcome to WNYC.

Jenisha Watts: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Arun Venugopal: Listeners, we want to invite you in as well. Perhaps if you grew up in poverty, experienced trauma as a kid, maybe you're working in ritzy professional spaces amongst those who grew up in some amount of privilege, tell us how you adjust. Do you hide the truth of your childhood? Do you mingle comfortably with your colleagues? Call us or text us at 212-433-WNYC. That's 433-9692. Jenisha, I know it's a long and complicated story, but tell us a little bit about how you grew up.

Jenisha Watts: I was born and raised in Lexington, Kentucky. My early childhood I lived in the Charlotte Court projects, and it was especially an area where a lot of low-income Black families lived with maybe single mothers. From there, I moved to the suburbs with my grandmother when I was probably in sixth-grade.

Arun Venugopal: I guess a lot of the story, your essay has to do with your mother whom you call Trina. Tell us a little about Trina.

Jenisha Watts: Trina-- my mom, yes, she was addicted to crack cocaine since I was in elementary school. The piece talks a lot about me navigating my life having a mom that's an addict and being the oldest of five siblings. I was the oldest and taking care of my brothers and sisters as my mom struggled with her addictions throughout our childhood.

Arun Venugopal: At the same time, you're growing up in this environment, it's very difficult for you and your siblings, as often you're the one who's helping raise them, but you have, I guess, this one thing that gives you some amount of hope and happiness, which has to do with your reading habits, correct?

Jenisha Watts: Yes, correct. Yes, reading. The books were a big part of me imagining a world outside of the world that I was living. Books was able to expand my mind, expand the opportunities, and has given me other things that felt tangible, other things that were in reach for me in my life outside of Kentucky, outside of my situation. It's [crosstalk]--

Arun Venugopal: Tell me some of the books-- Sorry, I didn't mean to cut you off, but were there some books that really you feel a special kinship with from that era?

Jenisha Watts: Yes. One book that my mom would always read was Curious George. It's interesting now, when, as an adult, I think about how that was the early-- That was the seeds of her planting into me how important it was to just be curious and to have a curiosity and to question things and to wonder. I do remember listening to her read Curious George a lot and just being able to just imagine, just thinking about things outside of where I was living. Then, the other books as a young child was The Baby-Sitters Club. I remember reading about Claudia in her friendship and also being adopted.

Arun Venugopal: Take us to the point in time when you're all together as siblings, but at some point, things start fraying, don't they, and you're separated, how old were you when that happened?

Jenisha Watts: I think we was probably separated when I was probably nine, and I think that's when I ended up moving to Florida with my aunt who had just graduated from the University of Florida State. The question is, what was it like?

Arun Venugopal: Sure.

Jenisha Watts: I think what it was like, I think, then, I was like any other child, I missed my mom and my siblings, but then I think as I meditate on it as I write about it now, as an older adult, it was pretty traumatic.

Arun Venugopal: Sure. One thing you note what about your mom is that addiction aside, you didn't have a confrontational relationship, as I understand it, with her directly.

Jenisha Watts: Yes, no. I think that's the thing that-- I think [unintelligible 00:06:15] fortunate about when I think about my mom. She's always been addicted, but one thing I've never doubted was her love. She's always shown that she loves her kids. Even when I have memories that didn't make it to the essay that she would be in our bathroom sobbing, and she would just be praying to God, just saying, "God, please just protect my kids." She's always been-- she's always-- If I went to the Tupac's song, when he's like, "Dear Mama," he's like, "Even as a crack fiend, mama, you always was a Black queen," and my mom, she was always loving. Even up until now, I was talking to her earlier, and I'm just like, "The world knows all the badness about you, and they can look at you and judge you," and she's okay with it. I think her allowing me to tell our story and to tell all the ugliness a bit, I think that's the ultimate act of love and unconditional love.

Arun Venugopal: At some point, you start clearly, well before you actually make it to New York and you work at People Magazine, and eventually you work at The Atlantic, where you are currently, was there a point where you started thinking that maybe you could, that there was a bigger world out there, one that you could claim a piece of?

Jenisha Watts: Yes, most definitely. I think when I moved to New York is when a world of possibility really opened, and I realized that-- Of course, I realized I had to work hard and it would be extremely difficult to get into that world, but I felt like it was within reach because I was working in media, I was working at some of the most prestigious publications. Yes, it made it more attainable. It made it something where I could touch. It was close.

Arun Venugopal: We're talking to Jenisha Watts who wrote about her story of escaping a childhood, a very fraught one witch her mother was addicted to crack, and a lot of deprivation, growing up in poverty and eventually making it to New York, where she is now a senior editor at The Atlantic. Listeners, if you have a story that you can relate to what Jenisha has written about or what she's speaking about, feel free to call us or text us at 212-433-WNYC. That's 212-433-9692. Jenisha, I'm curious, what gave you the confidence to leave your hometown and come to New York in the first place?

Jenisha Watts: Well, I had an opportunity to freelance at Essence Magazine for a month, and I always knew that I wanted to work with words and be in journalism. I think, at that time, I was in my 20s, and when you're in your 20s, you don't necessarily think of-- you're just fearless. I think at that moment, I was just acting on just the adrenaline of just being able to have this one-month temporary freelance opportunity, and I just decided to just take it. I didn't really think it through, except now when I'm looking back on it and I'm writing about it, I'm just like, "Oh my God, that was terrifying," but in the moment, it was just more of me having the opportunity and being able to just do it, just to pack up my suitcase and just move to New York.

Arun Venugopal: You open your piece with this lovely scene when I guess a mentor of sorts takes you to a brownstone in Harlem, if I remember correctly, and you're at a party at Maya Angelou’s, which I guess for almost any writer is going to be like a life event. Who was the person who took you there and I suppose opened up doors for you in this world?

Jenisha Watts: She was a literary agent herself. Her name is Marie Brown. She's actually still a literary agent. She knew this world. She worked in books, I think, around the '70s. She was an editor of Eugene Redmond, who was being celebrated at the event. I think she edited his book. She introduced me, or she surprised me, I didn't know where we were going, but I knew it was somewhere important. Yes, she introduced me to a lot of different writers at the event and just opened up this world for me.

Arun Venugopal: One of the I guess most extraordinary parts, I think of this of your powerful essay has to do with your decision to actually write about some of these very painful things, including sexual abuse in the family, things that a lot of families do not want to air, and the pushback you got, and the one person who really told you, "Yes, please tell your story," is your mother, Trina. Tell me about that because it seems like Trina is one person who otherwise I might think doesn't want these things to be known.

Jenisha Watts: Yes. Like I said earlier, her being able to allow me to tell the story is the ultimate form of unconditional love. I think writing about anything that is revealing or shows people's flaws I think is hard for anyone to digest. I think to the question about sexual abuse, it was difficult to write, but I felt that as a writer, as an editor, someone that works in media, I thought it was also my responsibility to also tell the hard stories, to tell the hard truths, to tell the stories that is easy for people to look away, especially when the characters in the story are Black and Brown people involved. I thought that was important.

Arun Venugopal: Absolutely. Well, we're going to have to leave it there for today. Jenisha, thank you so much for joining us today.

Jenisha Watts: Thank you. Thank you for having me.

Arun Venugopal: Jenisha Watts, senior editor at The Atlantic. She wrote this month's cover story in The Atlantic. Thank you so much. I'm Arun Venugopal, and this is The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Thanks to all you for listening.

[music]

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.