Oscar-Nominated Docs: Writing With Fire

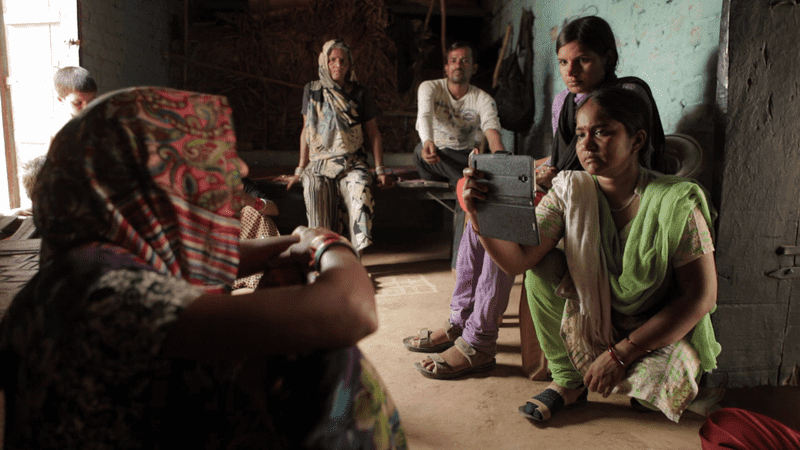

( Black Ticket Films / PBS )

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, again, everyone. Now, we continue our yearly look at the feature-length documentaries up for an Oscar in that category. We kicked off the series last week with filmmaker Stanley Nelson on his film, Attica, about the prison uprising there. Today, we're joined by the directors of Writing With Fire about a news organization in India run by Dalit women, Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas are with us from New Deli, where, I believe, it's in the 9:00 PM hour over there. Congratulations on your nominations, and thank you for staying up. Welcome to WNYC. Hello from New York.

Rintu Thomas: Hi, very, very big hello from Deli. That's so nice to be with you on air, Brian.

Sushmit Ghosh: Hi Brian, Sushmit here, looking forward to this chat.

Brian: Rintu, let me start with you. Why did you make a documentary about a news organization?

Rintu: I wanted to make a firm about feisty women and they just sort of happened to be journalists, so it worked out beautifully. I think the first time we met women of the news organization Khabar Lahariya, we realized that here is a group of people who have been usually written off from every story and yet were pulling a chair to the table and saying, “I'm here to tell my story.” A lot of things resonated, and we went off on a journey with them, took us five years to make the film, and here we are.

Brian: Here you are. Sushmit, the film follows three women in particular working at this newspaper, which is also in the film developing a digital online presence, like a lot of newspapers all around the world. Khabar Lahariya is the name of the paper, and it's in the state of Uttar Pradesh, but as you told someone in another interview, it's really about gender, cast, democracy, journalism, and technology. That's a lot so let's talk about some of those threads you've woven together. Tell us a little about the paper and the role it plays in Indian journalism as the only all women organization.

Sushmit: Yes, it's interesting. Most of the newsroom in India are literally manned by folks from privilege casts and usually more often than not, they'd be men. Khabar Lahariya essentially is a great template for what happens when you really diversify the editorial room. We discovered this news organization quite by chance in their 14th year. They invited us over when they were making a pitch from print to digital to the team.

What we then witnessed was women from the Dalit community, most of them who had not completed their school, many of them who had never experienced what social media was or technology, learning how to use cheap Chinese mobile phones, figuring out what Twitter is, Instagram is, how do you make videos, how do you edit videos to put it together to essentially translate 14 years of hard news into this new phase of digital news.

It was a big risk for them to pivot to digital. When we look back now, what had started off as just a couple of thousand views on new YouTube in 2014, 2015, is now a channel that's robust and running 170 million views. A lot of the news is consumed by folks from within the region, the state of Uttar Pradesh. Just for context Uttar Pradesh is the most populous state of India, if it were a country, it'll be the fifth largest in the world, and that's where Khabar Lahariya operates.

Brian: Gender, cast, democracy, journalism, technology, Rintu, most of the women who work at Khabar Lahariya are Dalit, what used to be called untouchable. The cast system is officially outlawed but still very much a part of these women's lives. What does it mean for the work that they do, that they are from a marginalized social strata?

Rintu: I think that's like central part to who they are and the rewriting of the story that they're doing for themselves and people from their community in Uttar Pradesh, the region that they function in. Being a journalist is typically meant that you'd be a man, and you'd belong to a dominant cast.

When women journalists who are covering crime, covering corruption, covering rights of the disenfranchised, in comparison to the mainstream media who would hire women to do softest bits like fashion, or food, or entertainment, I think the entire society sort of came face to face with the intelligence, intellect, and the force of the Dalit woman with a pen and who could now tell her stories in her own language and truly build a news organization from bottoms up.

That's where you see the beautiful intersection of gender cast happening in the film. The fact that with the power of an unfettered technology like the Internet, they were completely able to gallop faster and news [unintelligible 00:05:56] force and really hone in all that they represent as women from the Dalit community, who have never really had themselves even represented positively on screen.

Mostly, popular cinema would represent Dalit women as victims, someone who needs to be rescued. Or this superheroine, patronizing lens that happen where you characterize a woman as she can do pretty much everything, and yet she becomes somebody who's unrelatable, if you know what I mean. Here, we have the opportunity to really meet ordinary women with an extraordinary spirit and who are really scripting their own stories.

We just wanted to walk this journey with them, see them make this transition, and also represent them as colleagues, as bosses, as sisters, as friends. We don't see those kind of women's friendships or stories about organizations that are run by women in positions of leadership. Here was an opportunity to do everything and more, I think, and we just went like straight in, it was a running train, and we just hopped on.

Brian: A running train and we just hopped on, on their way to an Oscar nomination. Because if you're just joining us, listeners, we're in episode two of our annual series. Talking to all the filmmakers of the feature-length documentaries that have been nominated for Oscars in that category, the Oscar Award Ceremony, coming up on March 27th. We're hoping to get all of the nominees in on the show before then. If you heard last week, we kicked off the series with filmmaker Stanley Nelson on his film, Attica, about the prison uprising there.

Today, we're talking to the directors of Writing With Fire about a news organ in India run by Dalit women. Sushmit Ghosh and Rintu Thomas are our guests. I wonder if anybody happens to be listening in India, or from India, who's ever read Khabar Lahariya, that newspaper-- or now it's more of a YouTube-based news channel. 212-433-WNYC, or if you have any questions for our filmmaker guests, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer.

We'll hear a clip in a minute, but let me tell everybody, you follow three women in particular. Mira, a seasoned reporter, and two younger reporters she's mentoring, up-and-coming reporters Sunita and new to journalism and smartphones, Shamkali. Mira struggles to balance her work reporting and training others against the demands of her husband and child. While Sunita, despite her talent and ambition, knows her family pays a price, if she doesn't marry and “settle down”. Shamkali, who needs guidance on operating the smartphone with their English letters and on basic journalism, nevertheless, Rintu, they persisted.

Rintu: Oh, they did. I think that has resonance with each one of us. A lot of people who watch the firm come out of it and tell us that they're inspired. That's very strong, because the firm at the heart of it, through these three women with very distinct personalities and personal histories, is about courage and the different contours of courage. The courage it takes to speak up and sometimes the courage it takes to sort of stay quiet and weather the storm, and re-strategize. The courage it takes to ask uncomfortable questions, but sometimes you need to find the courage to sit in uncomfortable answers and, again, find a way to re-strategize.

We wanted to exist in these very, very complex spaces, and the women, each of them with their distinct background stories, or where they're coming from, and their distinct ambition of where they wanted to go as people, and yet together as an organization, gave us a lot of, I would say, space to explore these different aspects of their lives. That's what resonates mostly with people around the world. The film is a very specific story about a particular organization in a small part of India, but it's traveled to over 120 festivals, won awards and most importantly has been an audience favorite.

I think there's something there, when strangers meet across the screen and yet, there's a beautiful relationship on the basis of basic human, I think, feelings. People get a lot of courage from these women, when they watch it.

Brian: Looks like we have a couple of good callers lined up, but first, Sushmit, I want you to act as a translator for us, because the film is entirely in Hindi, not in English. Just to give folks a snippet, here's a clip of Sunita explaining her role and what's what to a group of men and their very patronizing leader, as she covers their demonstration, trying to get a road paved. This is 20 seconds.

[clip from the movie plays]

Brian: You get a little sense of the texture of that scene, just from listening to the sound, even if people who don't speak Hindi can't understand the words. Sushmit, will you do the honors of a translation?

Sushmit: Absolutely. Sunita is the feisty one in the lot, she's a maverick. She, I think, can stand up to anyone in the room without actually thinking twice about it. This was a moment where we were going towards an illegal mining village and stopped by the side of the road, and Sunita was surrounded by a huge group of men, I would say, about 50 to 60. Karen and Rintu were filming this scene. Basically, there was a man who challenged Sunita about her credentials as a journalist, and he questioned everything about her integrity and essentially reflected on how people perceive mainstream journalists in these region, corrupt journalists who basically take money to file stories, et cetera.

Sunita, being who she is, was able to sort of walk herself out of this very tense situation. Essentially, by the end of the scene, people came up to us saying, “Oh, please do this story for us, because no one's really covering it. This broken road is leading to like a lot of accessibility issues for ambulances, our kids going to school,” so on and so forth. It sits fairly early on in the film to set context up to the kind of spaces and geographies that the journalists are working in.

Brian: Since it's early in the film, I guess it's not too much of a spoiler to say that though she has to explain that she's not there to be bribed to put the story on the front page, the guy in the scene is so dismissive, but after her coverage, the road actually gets fixed.

Sushmit: It does.

Brian: The journalism gets results. You can go answer the door if you need to answer the door [crosstalk] Meanwhile, we take Rita in Somerset who's calling in. Hi, Rita, you’re on WNYC with the filmmakers of Writing With Fire. Hi.

Rita: Hi, Brian. I'm actually of Indian origin, and though I've been here for many years, I have an nephew who is in photo journalism. He expresses his dismay at how many of his colleagues are leaving India because of the fact that the Modi government has been kind of clamping down on people who write things, which are favorable to their point of view. There has been threats, there’s been death threats as well. I was wondering how these people are able to navigate that kind of landmine, where they have to tread carefully not to anger the government, the local governments, and how they manage that.

Brian: Sushmit, you want to take that?

Sushmit: Yes, sure. I think there is a certain nuance and sophistication with which the journalists at Khabar Lahariya are working. They've been around for 20 years now, they're celebrating their 20th year, and they have often worked in highly oppressive and media-dark spaces. When we were on the ground filming with them, they were able to manage their way through spaces that are conflict-ridden, spaces that are patriarchal. Spaces that are oppressive, with a certain kind of panache, but also a level of sophistication that is really a masterclass in what journalism is.

I think it's sort of like [unintelligible 00:15:41] to what they've been doing as journalists and really something, a template that more mainstream journalists should really follow.

Rita: Thank you.

Brian: Thank you. Patty in Princeton Junction you're on WNYC. Hi, Patty.

Patty: Hi, Brian. Thanks for taking my call. Very hearty congratulations to the filmmakers for the great reviews they are getting from international press and other media. Thanks again for telling this great story of courage from these women. The question I was trying to ask was just answered by Sushmit and asked by Rita, so I won't revisit the question. But is there a plan to subtitle this film in all the regional languages of India so that everyone can understand in all states of India.

Brian: Rintu, are you back? Do you want to take that?

Rintu: Yes. That would be a dream, really. I think this is a film that India needs to watch and Indians need to watch, and there's a lot of interest within the country. A lot of our earlier films-- we've been making films for 13 years now-- this is our first feature documentary, but we made a lot of shots, and we've made sure that these have been translated as much as possible for people across the country to watch. I guess once the euphoria and the dust settles down around the Oscar, we would make the film more accessible, and that would be the dream.

Brian: Patty, thank you very much. It's not just the Oscar nomination. You've already won two awards at Sundance, I see. The film will be shown on PBS next month. I'm curious what that's been like for you. If you think all the acclaim and maybe even an actual Oscar would help with any of the causes that the film deals with, from equality to democracy and beyond, Rintu?

Rintu: I sometimes go back into the edit room when the pandemic had just struck. Everything was shutting down, and festivals were sort of collapsing. Sushmit and I were just like, “Will this film ever get made? Will we ever have an audience? Will any festival ever take it?” I think fast forwarding it a year and a half, it's extremely satisfying to have had the opportunity to present the film across different countries in the world, different kind of audiences, especially in a virtual year.

In many ways the film has brought together a community of journalists, of audiences who typically usually don't go to film festivals but are now able to access films because of the virtual nature. It's been a huge galvanizing, I'd say, up until this point, and we want that to continue. We want the firm to have greater spotlight on the actual conversations that we should be having.

Sushmit: Just chiming in also over here, two things have happened. One is the work of Khabar Lahariya has now been amplified globally. They've been written about in The Atlantic, The New York Times, The Washington post, The Guardian, so the world knows of them now. The other conversation that's also now happening is how far can an independently-produced documentary from the global south come? Because when you think about the Oscars, you're always thinking about the big films and the flashy titles, and all the money that goes behind it, but independently-produced films that are coming from an international audience for Americans, can they do well?

I think this film has actually started a new conversation within the industry itself. I think these are two important things that we've been able to sort of hit as milestones. I hope it’s able to pave the way for new conversations.

Brian: Really interesting. We're going to be out of time in a minute, but Sushmit, the final thread that you've woven into the film, and maybe it even relates to the answer you were just giving about the film industry, is what's happening in India and Uttar Pradesh specifically as this is all going on, the rise of the Hindu nationalist party, the BJP, and Prime Minister Modi. I'm just curious if there is any government pressure against distribution of the film, or how that impacts the rise of this alternative news organization that the film is about, women-run and Dalit-run?

Sushmit: Not really. I think there's been a lot of love in the country. There's a lot of excitement in the country because this is not an anti-anybody film. This is a pro-justice and pro-democracy film which people are celebrating. I think that's the lens with which we've also presented the film to the world. Here is a modern template for a modern journalistic institution that is meant to essentially ensure systems of justice are available to everybody, democracies are transparent.

I think that anyone who believes in the idea of India, or a vision of democracy would essentially-- I shouldn't be saying this, but I can’t but fall in love with the characters of the film and the film itself. That's essentially been our approach, and we're looking forward to bring the film back home. There's massive anticipation around it.

Brian: We leave it there with Rintu Thomas and Sushmit Ghosh. Their film Writing With Fire is one of the nominees for the best feature-length documentary at this year’s Oscar ceremony. That will be on Sunday, March 27th. Then the next night, it makes its television debut on PBS's Independent Lens. That will be 10 o'clock PM-- mark your TV calendars-- on Monday, March 28th. Rintu and Sushmit, thank you so much for sharing your film and your process with us.

Rintu: Thanks for having us Brian.

Sushmit: Thanks so much.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.