An Ode to The Core Curriculum

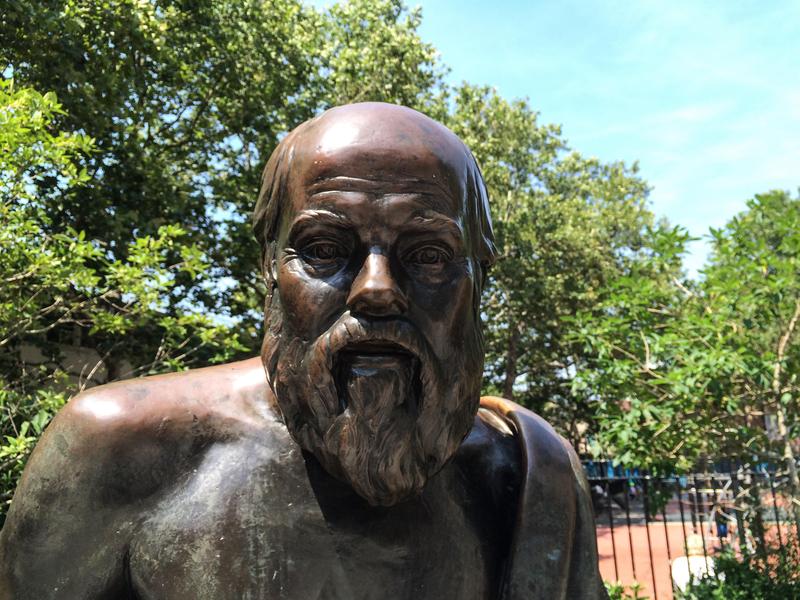

( Stephen Nessen / WNYC )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Is liberal education dying in our colleges and universities? Are college degrees now just a requirement for a better job, and graduate programs in place for more and more specific research?

Our next guest Columbia University, Professor Roosevelt Montás argues that colleges and universities are going in the wrong direction and that they should be, "cultivating whole persons" through transformative texts. Montás is the senior lecturer at Columbia Center for Latin American Studies, and director of the university's Freedom Citizenship Program, which introduces low-income high school students to Western thought through foundational texts. He's the former director of Columbia Center for the Core Curriculum. He did that from 2008 to 2018.

Montás was also an immigrant to this country from the Dominican Republic in the 1970s, a lived experience that informs his perspective. Professor Montás' new book is called Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation. Hi, professor. Welcome to WNYC. Thank you so much for coming on.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Thank you, Brian. It's a real privilege to be here with you.

Brian Lehrer: Why write a book on the importance of Western classics in 2022? What contexts over 200 or 2,000 years old tell us about the issues we have today?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: The issues that we have today have a past, they have a history. Understanding that history, understanding the evolution of the institutions, of the categories, of the norms that we have, allows us insight into how they work, into how we can intervene in them, into why they matter. It contextualizes the significance of the problems of the present, it puts them in a big picture.

This awareness of the past can really provide the flexibility and provide the openness so that we don't go into a tunnel vision about our own ideas and the significance of our own positions.

Brian Lehrer: We'll get into the core curriculum and whether it should be in 2022 what it was in 1982 if it should exist at all. To go to your personal story a little bit, which you certainly tell in the book, I see you were born and the DR in 1973 and came to what everyone called the-- Why don't you say it because I'm going to mangle it? It's that Nueva York, right?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: It's [unintelligible 00:02:58]. [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: In 1985.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Yes. We refer in Dominican Republic to all of the United States as [unintelligible 00:03:09].

Brian Lehrer: [laughs] So do everybody else that lives in New York, which could be a problem sometimes. Then in 1989, as a sophomore in high school, you found two books in the garbage that you say, "changed your life." You write, "In ways I could not have understood. Before me, was the treasure I had come to America to find." What were those books?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: It was a collection by Plato recording the last days of Socrates. The other was a collection of plays by Shakespeare and Marlowe. It was actually that first one that I started reading, and that really opened up an entire new way of thinking for me and that gave me a taste for what some people call the life of the mind. Gave me a taste for a way of living, a way of approaching your social reality, a way of positioning yourself before your society that proved to be transformative and to really shape the rest of my life.

Brian Lehrer: You came to the United States with your older brother to live with your mother who had been living here in Queens for two years. You write that you landed at JFK International Airport with a head full of lice and a belly full of tropical parasites. "In many respects, I was an unlikely candidate for the Ivy League." How'd you make it to Columbia?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: I had the great fortune to have important mentors and teachers. This is something whose importance I think is especially evident in the lives of low-income traditionally marginalized, often immigrants the way I was. It is people along the way that transmit the education. Education is something that happens between people from one person to another. It is not simply the books or is not simply the school, it is individual.

I had the good fortune of meeting people in my high school, John Bond High School in Queens, who took an interest in me, who encouraged me. The same thing happened when I got to college, I found professors and administrators that took an interest in me. It's why today, I am so committed to liberal education, which is always a personal kind of education. An education that takes the individual in his or her specificity, and subjective experience, and works on that, concert itself with that, not simply with equipping the student with particular skills or particular competencies.

Brian Lehrer: Now, your book on one level is a defense, not just of liberal education, in the sense of educating the whole person like you were just referring to not just career crap, but a liberal education founded on Western classical texts, especially for students who say who come from minority and/or low-income backgrounds. You write that you don't have to tell these "disadvantaged" students, about the value of a liberal education, they know.

You say, "We condescend to them when we assume that only works in which they find their ethnic or cultural identities affirmed, can really illuminate their human experience," from your book. Where do you find that argument most? The argument that only certain culturally relevant texts resonate with, "disadvantaged students," and not also the Western classics.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: It's part of a whole movement. Sometimes it's identified with politics or with the academic left or with social justice, but it's part of our whole intellectual awakening that happens in the '60s '70s into the '80s, where suddenly, people began to question the received pieties and verities and paradigms. A culturally triumphalist celebration of the West that has been traditional in the academy and which had often been implicated in white supremacism and exclusion.

That impulse to bring down the idols, I think, also generated this unhelpful attitude that actually these texts are somehow inappropriate, not useful, oppressive, as instruments of education for people of color, for minorities, for people that are have been historically underrepresented in universities. It's an easy argument to see, but it's also extraordinarily damaging to precisely the people for whom these are tools of empowerment, for whom this text, this tradition opens door both of action, but also of insight into the very structures that had kept them marginalized.

Brian Lehrer: Would it be accurate to say you're not making an either-or argument or a case against including more contemporary works by authors from historically underrepresented backgrounds in the academy, it's just a matter of not throwing Socrates and Plato and other more recent Western classics overboard entirely?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Absolutely. Sometimes, there are two arguments that get conflated. One is an argument for a diverse set of texts, let's call it a diverse canon, and an argument for a contemporary canon. Because those, in some sense, the forms of diversity that we tend to highlights today, ethnic diversity, religious diversity, socio-economic diversity, that kind of diversity is represented in the canon in the 20th century, especially after the Second World War. It's notably not represented in antiquity.

If you think of diversity as including chronological diversity, so that we want an education that not only represents the wide population variety that we have say, in the United States, but you want a curriculum that represents the whole span of learning, and expression and philosophical inquiry, that has led us to where we are.

When you take that meaning of diversity, then we're talking about a lot of ancient texts, and there you're not going to have many women, you're not going to have what today we call people of color, you, in fact, not even going to have anybody who wasn't an absolute cultural elite. That status is no reason for us to reject those texts. In fact, they are just as important despite the fact that they do not represent our ethnic, religious, socio-economic diversity today.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we open up the phones, what is your experience with the classics? Did any Plato dialogue or Shakespeare play, change your life and especially if let's say you don't come from white western European heritage? If so, give us a call at 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, as we talk with Columbia Professor, Roosevelt Montás, senior lecturer at Columbia Center for Latin American Studies and director of the university's Freedom Citizenship Program, which introduces low-income high school students to Western thought through foundational texts.

His new book is called Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation or maybe you want to push back on what he's arguing here. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer. You go further than we've even discussed so far. You write that today's academic criticism bends toward moral reprimand. It doesn't just illuminate, it burns. It doesn't just judge, it condemns. It doesn't just reject, it cancels.

I think you were talking about criticism of the Western canon but I wonder what your take is on the recent trend of book bannings we're seeing in schools more coming from the right. Is this intolerance of popular ideas on both sides of the aisle in your view?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Indeed. I think that we are in a what you might call this corrosive environment that is becoming increasingly illiberal and it's being driven to closeness, narrowness, kind of ideological homogeneity from both ends. From the left, you have what is sometimes and always derisively called cancel culture. That is the idea that certain forms of speech, certain speakers, or certain forms of expression are not allowed.

That they pose such a threat and such harm to listeners so they should simply be banned. On the right, you have a kind of hysteria over things like critical race theory, which for one thing, nobody can say what it actually is, or any kind of liberal reassessment of American history, anything but a triumphalist presentation of America as kind of the God-given providential blessing to the world.

On that side, on the right, you have this impulse to censor. There's an effort, at least, to homogenize the discourse, an effort to police thought, to police expression. It's lamentable that it comes from both sides and both extremes of the political discourse have gone into a kind of frenzy into a kind of hysteria that is doing a lot of damage to the possibility that we have to rationally work through very serious problems and disagreements that we do have.

Brian Lehrer: Could that be a false equivalency though? Because on the one hand, banning critical race theory when it's not even being taught, supporting a triumphalist, as you called it, Western view of history is just wrong and it's not history based on fact, and based on broad enough perspective to be historically meaningful. Whereas saying things that are racist or sexist or otherwise hurtful to people who are trying to live as equal as on campus, when they may be in the numerical majority on campus. That whole conversation has more of a foundation in reality and on real harm to people trying to make it in the world.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: I think that there is an asymmetry in the historical power structures where speech or actions that pick on marginalized, hurt groups that have already been historically the victims of oppression, exploitation, as opposed to censorship that comes from the places of traditional power. Certainly, there is an asymmetry in that and it's something that we should be alert to in the way that we metabolize and think about specific instances.

It's hard to generalize but that we need to be committed to an open dialogue and to permitting, tolerating ideas that are racist, ideas that are misogynist, ideas that are hurtful to people. The way to address those ideas is to counter them with better arguments, to insist on our rights, to insist on equality, to insist on human dignity.

Shutting down the argument never works. Shutting down the argument doesn't, in fact, address or educate or transform the opinions that you're battling against. I think we need to return to a sense of we can tolerate, we can handle, we can do discursive battle against bad opinions, rather than the easier impulse to say is this is hurtful, this is threatening, this is echoes, forms of speech that have been used to keep me down, therefore, I need to shut it down.

Brian Lehrer: As we continue with Columbia University, Professor Roosevelt Montás, senior lecturer at their Latin American Studies Center and author of--

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Not Latin American actually,-

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: -Brian. It's American studies. I don't want to-

Brian Lehrer: Oh, American studies.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: -take over the turf of my Latin American professor and colleagues. I do American studies, which is largely US.

Brian Lehrer: I apologize. I was given that title and so I'm happy to collect it, the Columbia Center for American Studies.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: For American Studies.

Brian Lehrer: You do direct the university's Freedom Citizenship Program, which introduces low-income high school students to Western thought foundational texts?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Indeed. I am the director of the Freedom and Citizenship program.

Brian Lehrer: You used to be director of the Core Curriculum Program?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Yes, that is all right.

Brian Lehrer: Just making sure I have all this right as we go to a few phone calls. Did I see correctly that you teach or have taught moral philosophy?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Yes, that's right. I teach in the Columbia Core curriculum. The program I directed, one of the courses, of course, that I've been teaching in recent years, is roughly speaking a survey of important works in moral and political thought. In the roughly speaking Western traditional, all these terms are kind of problematic, but European, Mediterranean cultural heritage and into the new world once you get into the 17th, 18th, 19th centuries.

Brian Lehrer: Patty in Princeton Junction, you're on WNYC with Professor Montás. Hi, Patty. Oh, I need to actually click her onto the air. Now, we have you, Patty. Hi, there.

Patty: Hi, Brian. I teach physics to college students and I see all around me this professionalization of college education, where skills rather than knowledge, are emphasized. I'm not saying that skills should not be emphasized but what has also been forgotten is how to integrate ideas from the humanities into the sciences and engineering and other professional education.

In my class, just two days ago, because it was Valentine's Day, I gave a physics problem to students incorporating the story of Romeo and Juliet. I asked students to calculate something when Romeo ties a Valentine to his rock and throws towards the balcony. I was able to talk something about Romeo and Juliet and Shakespeare, but I'm not sure I was able to reach students. I also feel tremendous inequality in high school education.

I know that my daughter, she went to one of the higher-performing schools, where in middle school, an English teacher taught them Julius Caesar. I feel that we are all worshipping at the altar of technology and we forget that technology is a way of doing but science is a way of knowing and arts and humanities are ways of feeling. I just wanted to share that with you. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. Even for you as a physics professor, you want to make sure the arts and humanities aren't dropped.

Patty: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: From a whole-person education. Patty--

Patty: I feel that's what we need to make sense of our lives today.

Brian Lehrer: Patty, thank you much. Professor Montás, do you want to react just to that?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Yes, I absolutely agree. This is quite critical because, while it is true that college education should equip our students for jobs, it should equip our students to be productive, successful in the economic marketplace out there.

There's another dimension of college. We meet students who come into our classrooms, I'm speaking as a college instructor now, who are questioning very deeply the whole cultural ethos in which they're in, the value system that says that making money, accumulating power, accumulating prestige is the point of life. They are in a condition, that I call a condition of freedom. Every one of these individuals has to organize their lives and develop a value system that's going to give meaning to the activities in which they engage the professional activities.

We do them a tremendous disservice if we don't take that condition seriously. If we don't organize a portion of the education, not all of the education, but a portion of the education that takes that condition of freedom seriously, that takes this existential moment in which they are, in which they have to organize a notion of their own good, a notion of the human good into which they're going to articulate their own life activity.

We need to give them tools to do that. We need to give them tools to fulfill this function of a free individual in a free society. That's not technical knowledge.

Brian Lehrer: This diminution of the core curriculum or even abolition of the core curriculum on so many college campuses, Columbia where you teach not included, do you see that more as coming from the progressive left that you were describing before that sees the core curriculum as patriarchal and hierarchical into Western philosophy oriented? Or do you see it more as from what Patty was decrying, which is college becoming just a glorified trade school, and not being about educating a whole person anymore?

Professor Roosevelt Montás: I think both pressures are at work. There is outside pressures that have to do with the fact that college, in a way, if you think of college as liberal education, it is countercultural. It swims against the prevailing current, the prevailing sensibility where we want something that's practical, we want something that's pragmatic. We want to equip our students to go out and be successful by which we usually mean, wealthy, productive. That's the culture.

You can see that reflected in the fact that throughout the country, state legislatures are reducing funding for public higher education, especially public higher education that is focused on liberal arts because those things are in the public mind seen increasingly as frivolous and not essential to an education. Those are outside pressures that come from the general culture.

Then there are inside pressures that are often ideological, and often, frankly, budgetary. Universities have found themselves under market pressures to offer a product to a consumer that they can vouch for, that they can say this is worth your investment. Those pressures, as they come inside the university, have found a convenient ideological justification in these criticisms of the canon, and these criticisms for liberal education.

I think universities have often been eager to dismantle serious liberal arts program. One of the ways that they tell themselves, one of the ways that they justify that is to say, this tradition is too contest, that this tradition is too problematic. This tradition doesn't really fit. There's no consensus even within the faculty about the value of this tradition.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a tweet that just came in that I think you'll find entertaining. Listener writes, "We named our seven-week-old son Odysseus after Homer. It's quite surprising how many people ask how we came up with a name, never heard it before, and don't know how to pronounce or spell it, makes me sad the lack of education of the classics." Writes that listener who just named their kid Odysseus.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Odysseus, wow. Ulysses which is the Roman version of that name, that is more common and everybody will know the odyssey just as a word in English. It's remarkable to me how names survive.

I have two children, one is named Arjuna and the other one a four-month-old is named Artemis. Something about these names to imagine that people have been saying these names, these words and referring to people by that name for thousands and thousands of years, that you link yourself to a depth of human experience, a link of human experience that goes back so deep, even beyond any records that we have. It's quite an extraordinary thing.

I love ancient names, whether they are from the western classical tradition, like Odysseus and Artemis, or from any other tradition like Arjuna from obviously an Indian tradition. There's something powerful about that. It's one of the values of the classic that it links you into this long chain of other human beings that have experienced the essentially similar existential condition of being human.

Brian Lehrer: Let me go through a couple of more calls real quick before we run out of time. Nora, in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Nora. I'm going to have to ask you to keep it to about a soundbite at about half a minute for time. Thank you so much for calling.

Nora: Hi. This is more as a comment. I came to this country in 1984 from Nicaragua. I did two years of high school here. The counselor that I had, basically told me to forget about college and just find a job anywhere else, but not a higher degree. Thanks to my sister, I do have a master's degree in science from the New York [unintelligible 00:26:46] School, and I have a good job. Have I follow that counselor advice, who knows what I will be there right now.

Brian Lehrer: That might have low expectations for you as an immigrant from Nicaragua, or that might have been dismissing of the value of a college education for its own benefits, as opposed to just technical training, probably a combination. Nora, thank you for that story. One more, Desiree in Park Slope. Hi, Desiree. You're on WNYC with Professor Montás. We've got about 30 seconds for you today.

Desiree: Hello, professor. Thank you so much for speaking.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Hi.

Desiree: I grew up in a very rural southern town in the '70s, and reading is what saved me, learning how to read. My grandmother threw all kinds of books at me even though she was not literate, Tolkien, Shakespeare, any kind of books she could put in front of me. I'm the first person in my family to have a college degree and to go on to have a graduate degree and to be a librarian. I was a university librarian for 10 years.

I know the value of understanding where the people you read were influenced. Anything you're reading, Toni Morrison is influenced by those classes. It helps you to understand the continuity of thought and whether it's rebelling the thought or being inspired by the thought. It's really important that poor working-class kids get the experience of living the life of the mind, even if it's just for four years.

Brian Lehrer: Desiree, thank you so much. Let me read one more tweet from a listener, and I'll give you one minute to say the last thing. I'm sorry. Now, as these tweets go by, this blanked off my screen but here it is. What does the professor think about his fellow Dominican immigrant Dan-el Padilla Peralta's mission to "save the classics from whiteness."

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Dan-el is a good friend. We teach together in the Freedom and Citizenship program where we work with low-income, first-generation college aspirants and we teach them some of these books Plato and Aristotle. You had Shaun Abreu on your show earlier this week, who is an alumnus of our class. Dan-el has battled, as a person of color in the classics discipline, has battled a traditional atmosphere of exclusivism, elitism, even racism within the classics discipline. He has done some really extraordinary work in challenging those paradigms and in trying to move that discipline towards a more open, a more inclusive, a more racially conscious posture. I absolutely support that.

That is different than the idea which is often pinned on Dan-el and of the people who share his views that the classics are not worth our time. That the classics are somehow not fitting tools to educate contemporary young people of color or people from marginalized communities who are not represented in the very old classics. It's a bit of a complicated argument, but Dan-el I think is doing really important work challenging some very entrenched and noxious attitudes within the discipline of classics.

Brian Lehrer: There we leave it with Columbia Professor, Roosevelt Montás. His new book is Rescuing Socrates: How the Great Books Changed My Life and Why They Matter for a New Generation. Thanks so much for coming on.

Professor Roosevelt Montás: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.