NYC’s Involuntary Hospitalization Policy, One Year Later

[music]

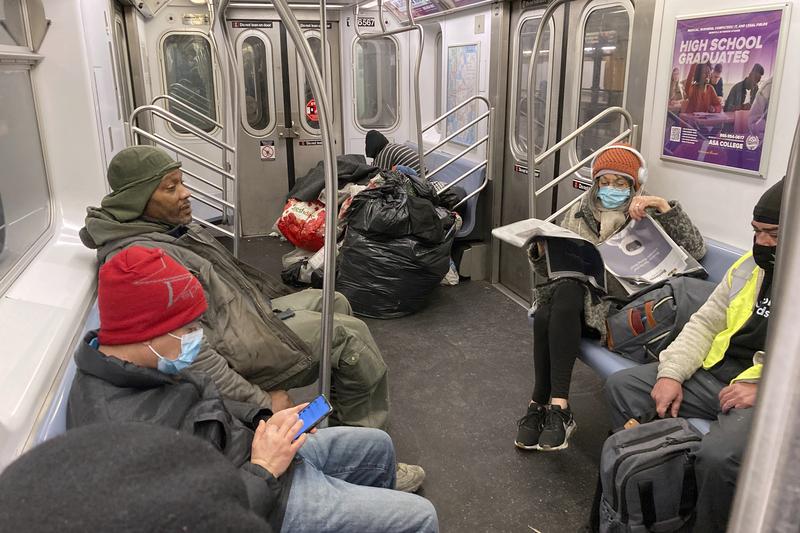

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. It's been a year this week since Mayor Eric Adams unveiled his controversial plan to involuntarily hospitalize some people experiencing severe mental illness on the streets of New York City. Under this initiative, first responders including the NYPD, are tasked with assessing if an individual can "meet their basic needs". If not, they might be transported to a hospital regardless of whether or not they want help. The goal of the administration was to meet the needs of our expanding unhoused population, those like Jordan Neely, the 30-year-old Black man who was killed in a chokehold by a fellow subway rider during what appeared to many to be a mental health crisis.

More often than not, people in situations like Neely's don't receive attention until they are harmed or they've caused harm. In this vein, the goal was also to help New Yorkers feel safer by lessening encounters with those who are clearly suffering and potentially volatile. Let's look at the results of this policy over year one and revisit some of the questions around it from when it was announced. Has the mayor met his goals? Have the concerns brought up by opponents of the plan come to unfortunate fruition? Joining us now to recap the first year of involuntary hospitalizations is Maya Kaufman, healthcare reporter for Politico. Maya, thanks for coming on WNYC today. Hi.

Maya Kaufman: Thanks so much for having me, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Mayor Adams' office has announced that more than half the hardest-to-reach New Yorkers. That's an official list. I believe that they maintain the hardest-to-reach New Yorkers have moved from street into care, their words, in the year since this mental health plan was unveiled. What's the fine print there? Who are these hardest-to-reach New Yorkers and how many of them have been helped?

Maya Kaufman: Yes. There are two top 50 lists, as they're called by providers, and these are these hardest-to-reach New Yorkers who often have been known for years to the types of nonprofit organizations and city agencies that do outreach to homeless New Yorkers. They're known for having more severe needs. It might be severe mental illness or substance use concerns, a variety of things. There's a list for people who are on the streets and parks, and then one for folks who are often found in the subway system. City Hall says that 54 of those 100 people in the last year are now in hospitals, or in supportive housing.

They credit the policy that Adams unveiled one year ago, as you described it with basically having led to those results,

Brian Lehrer: What does helping these individuals look like? That's the language that they use, helping these individuals. Where do they end up? What happens once they're actually removed from the street involuntarily?

Maya Kaufman: I'll answer that with an example that was described to me by a provider that works for the organization Bronx Works in the Bronx. They do street outreach to homeless New Yorkers. One example, it was actually on Christmas of last year, they came across a woman who the providers had known for quite some time. She was on an outdoor subway platform in the freezing cold and had bugs on her feet. She was having trouble walking because her feet were so swollen, and they invoked this directive basically that brought her to a hospital where they were able to give a psychiatric evaluation, attend to her medical needs.

Then eventually move her into supportive housing where she has her own placement today. Of course, that's a very rough summary of what happens. It takes a lot more time than that, but the idea that providers say is behind all of this is to attend to those acute needs by bringing people into hospitals who might be out in the freezing cold and not properly dressed for that because of perhaps their lack of insight into their condition. The hospital treats them for those mental health concerns and for medical concerns that they're currently experiencing, and then help them find a housing placement.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we invite you to help us report this story. Are you perhaps a person who has been removed from the streets involuntarily by the NYPD or any other first responders? If so, how did that go for you? Did it help you in any way? Or are you a first responder yourself or at all involved with helping those living on our streets? If so, how have you seen this plan take shape over the last year for good, for bad, or mixed? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or with any questions for our guest journalist Maya Kaufman, who reports on healthcare for Politico. 212-433-WNYC, call or text 212-433-9692.

The numbers of people they're saying have been placed into some kind of supportive housing compared to the numbers that they're saying have been removed from the street involuntarily in any way over the last year, seemed to be widely disparate. I wonder if you could get into these numbers a little bit more for us. It seemed, and I don't know how precisely they've released anything, but the impression that I got was maybe a few dozen have gotten in some supportive housing solution, but hundreds or thousands have been removed at some point. How much of that can you clarify?

Maya Kaufman: I would love to dig into the data, and unfortunately, we only have a really limited snapshot from City Hall to date about what exactly happened here. When we're talking about the 100 people on these two top 50 lists, we know that 40 of them now are in supportive housing. Again, the administration credits the involuntary removals directive with having led to that. It's important to remember that that's not the entire universe of people who are being subjected to this policy. What else we know is that at least since May, which is when the city feels confident about the accuracy of their data.

About 137 people per week have been involuntarily removed, meaning brought to hospitals for evaluation and potentially admission into a hospital due to apparent mental illness. Or there's a whole universe of reasons why someone could be "involuntarily" removed. This includes people who are brought into hospitals by police. It includes people who are brought in by clinicians and street outreach teams. There's a lot wrapped up in that, but at least for that 137 per week figure which is a weekly average, as we've been told, we don't really have a sense of the outcomes of if those people were admitted to hospitals or they were just released because it was determined that maybe they were brought in wrongfully.

We really have no sense right now what happened to those folks, who they are of certain populations have been disproportionately impacted. How many of that 137 is specifically under this criteria of unable to meet basic needs versus what the criteria was before the imminent risk of harm to self or others? There's still a lot of numbers that we're waiting on and that we've asked for and we think that City Hall has some of this information internally. We know that they're tracking it at least for the 100 on the two top 50 lists, which was the priority population that they wanted this directive to target. We don't really know what exactly is being tracked for everyone else. It's really an open question. That could be a lot of people.

Brian Lehrer: Maya, when Mayor Adams first announced the policy, he talked about the revolving door that there had been previously. People would be removed for these reasons of not being able to meet their basic needs or appearing to be a potential threat to themselves or others, but they wouldn't be kept in the hospital very long. Part of this program was to actually keep people hospitalized against their will longer until professional staff made some kind of determination based on, I'm not exactly sure what criteria that they were safe to release. Do you know anything about that aspect? Did the criteria for release change, and people have been held for much longer than in the past?

Maya Kaufman: We don't know how the length of hospitalization has changed. That's, again, another number that we haven't gotten from the City, but the law remains the same, and there's pretty strict standards about when someone can be admitted to a hospital against their will.

The first step is to take someone to the emergency room, and they can be held there for a limited amount of time for observation and for evaluation, and then a psychiatrist has to attest to the need for involuntary treatment, like administration of medication or for admitting that person against their will. There still are those guardrails, and there's courts and judges that have to approve these types of measures, so that hasn't changed.

What the city says has changed is that at least in the city's public hospital system, NYC Health and Hospitals, where a lot of these people are often brought to ERs, they've set up a new system of communication with the teams that are often bringing people in these street outreach teams that are generally run by non-profit agencies that contract with the city, and they have these dedicated emails and phone lines where providers can say, "Hey, I have someone who I'm bringing in involuntarily. This is what happened when we encountered them. This is why we're bringing them in. Here's what we know about this person's case or history, and here's what we would like to see happen. We want them to get this medical care. We want them to get a psychiatric evaluation."

All of that kind of communication as City Hall and providers have said it has really helped for people to actually stay in the hospitals a little bit longer, which as they know, in their words, is beneficial because what we were seeing a lot before all of this was that people might get some medication that temporarily stabilizes whatever's going on with them, whether it's medical issues, mental health concerns, things like that, and then being released basically back onto the street, and that's basically just putting a band-aid on what's going on.

As the providers say it, now that we have more communication with the hospital, they're actually attending to a wider universe of the person's needs and keeping them for longer so that they're actually really able to stabilize. We're able to actually help them more in the long term, get referrals to services, housing, other things that they might need, rather than just put them back into the situation that they were in to begin with.

Again, that's only public hospitals. The private hospitals is still, I think, a work in progress in city halls, trying to meet with them to establish the same kind of setup.

Brian Lehrer: Karen in Brooklyn has a story to tell. Karen, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Karen: Hi. Thank you. I have a situation where a gentleman who used to work for me stopped taking his medication and slowly sank into total insanity. He's now homeless. He sleeps in the pit by my cellar door. He refuses to leave my property. He does the small bits of vandalism. He's been arrested numerous times. He's been picked up by Department of Mental Health numerous times.

Sometimes he's back within an hour, sometimes he's back within two weeks. Two weeks is the longest he's been gone, but he's always back, and there's absolutely no change in his demeanor or anything like that, so a change of revolving door has not happened. I have been to the police department, had a long conversation with them, and they felt that there was nothing that they could do until he harmed somebody, and his vandalism peaks a bit, but absolutely, it just keeps going on. It's over a year.

Brian Lehrer: Karen, thank you for your call. What a sad story. Maya, can you put it into any kind of context? Obviously, that's one story. It doesn't tell us the pattern of what's going on, but it appears to that person that the revolving door is revolving away.

Maya Kaufman: Yes, I've heard a number of stories like this, and there's been not necessarily a lot of willingness always on the NYPD's part to undertake these kinds of involuntary removals. It's not primarily what they do, and for a lot of advocates, they say, "Yes, we don't want police to handle these cases." That's where the outreach teams come in, who often have mental health experts going around the city, and oftentimes when you see people who are homeless again and again, there are outreach teams who know them often for a long time and have made repeated contact with them, and offered services.

The idea as the administration puts it behind something like this directive, is that they would potentially be able to bring someone like this individual to a hospital without any sign of imminent violence or an imminent risk of harm to someone else, which historically had been when the NYPD and others would bring someone to a hospital. We've been told that first responders have all been trained on this criteria, the unable to meet basic needs criteria, but that story certainly suggests that NYPD officers are still not well versed in the different criteria, even though City Hall says 95% now of first responders have been trained.

Brian Lehrer: Last question for now, because we do have breaking news that we're going to get to, and this would've been the end of the segment anyway, but there's a tease, big breaking news about our local congressional delegation in just one second. When the policy was announced a year ago, involuntary removal of people on the street considered unable to meet their basic needs, critics were concerned that the NYPD was tasked with responding to these kinds of mental health crisis calls too much without the proper training that mental health professionals would have.

I'm curious how they've rolled that out, and also whether the NYPD or the mayor would say that the streets are safer now because they may not have wanted to admit that a year ago, but I think one of the main reasons they did it was because a lot of other people were feeling unsafe on the streets after some high profile attacks by people in mental health crises.

Maya Kaufman: The mayor does say more people are off the streets, but it's really important to note that we don't actually have data as of yet on how many of these "involuntary removals" have been done by police versus other people who have authority under the law to do them. These street outreach teams of mental health workers and other types of outreach workers who go around the city, social workers, that kind of thing.

We don't know how much the NYPD is using this. The NYPD didn't really even track this before this directive got issued. They had data on how many people they would bring to hospitals, but not whether it was voluntary or involuntary. They didn't have that breakdown. We don't actually really know. We do have a sense of what the training is like, though on Politico, actually published those materials, which we obtained, and it's basically a brief video and a PowerPoint presentation that the officers are given.

Of course, critics say that's entirely not enough for the kind of cultural shift that they want to see among, especially NYPD officers, and making sure that this is implemented appropriately and that people's constitutional rights aren't violated, and there are cases that that has happened, which City Hall has basically said NYPD officers have been trained and they are accountable, and they have great instructions now from us and it's clear. The story that we just heard from that caller indicates that that's not necessarily the case universally.

Brian Lehrer: Maya Kaufman, healthcare reporter for Politico. I know you'll keep tracking this during year two, to see how it proceeds in the interest of everybody or not. We will, of course, as well. Maya, thank you for coming on today.

Maya Kaufman: Absolutely. Thanks so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.