New York's Unfulfilled Legal Cannabis Rollout

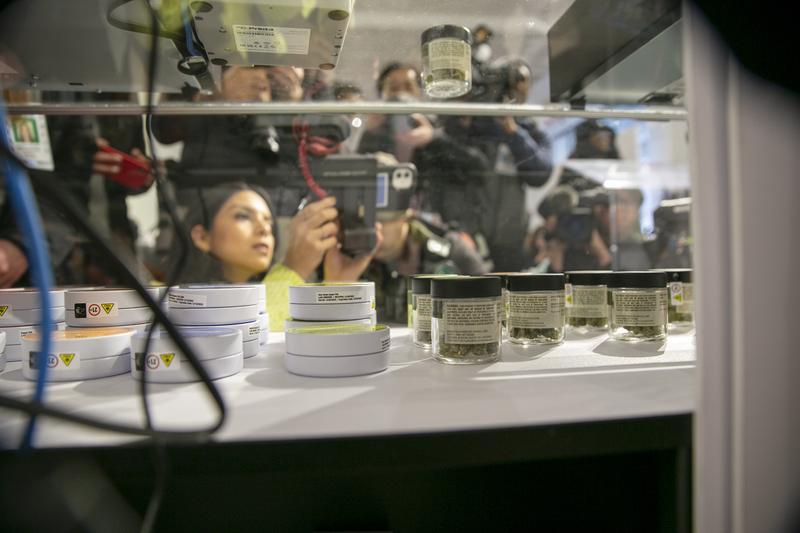

( AP Photo/Ted Shaffrey )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. The latest article by New Yorker staff writer Jia Tolentino begins with a hilarious moment in a certain way in which a convicted marijuana dealer named Howell Miller gets a tip from another person incarcerated with him, who happens to be Anthony Wiener. Yes, that Anthony Wiener, the disgraced former Congressman.

Wiener tells Miller in prison that New York state's new legal cannabis law includes first priority for dispensary licenses for people with marijuana convictions. Jia calls it legal weed as reparations program. That encounter with Anthony Wiener was years ago, but as you may have noticed, New York still has very few legal dispensaries open.

The heart of the article is about why, including some of the difficulties of doing legal cannabis in a more social justice-oriented way than any other state. There are some successes, which he also names, some broken dreams of people who are promised better. Some hope for the future, yes, and even a dispute of whether New York weed is of lower quality than that in other legal states because of certain growing rules. The article is called In the Weeds. Jia, always good to have you. Welcome back to WNYC.

Jia Tolentino: It's great to be here, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Anything more to say about that encounter in prison between Howell Miller and Anthony Wiener? Maybe it changed Miller's thinking about his future or anything else.

Jia Tolentino: Well, Howell Miller, like so many people, frankly, Black and brown people who were incarcerated over marijuana, he was having this experience where he was in jail watching people and mostly white people with considerable amounts of capital behind them get quite rich doing the same thing that he was in prison for. He was like, "Just why am I still in jail?" Then Wiener told him about this program called the Card Program. He ended up applying, and I just want to say Howie Miller did get his license. Hopefully, there'll be a store, Two Buds in the Bronx, hopefully, open this spring.

Brian Lehrer: All right, look for Two Buds in the Bronx, weed users in the Bronx, open by Howell Miller, who leads off Jia Tolentino's article in the New Yorker. The idea of legal weed as reparations, it has several components. Can you lay some of those out for us?

Jia Tolentino: Right. New York with its legal weed rollout, as you said, tried to do something that no state has even really tried to do with anything near this level of commitment. Certainly, no state has succeeded in achieving anything like social and economic equity in its legal weed industry because this is a product that was used as a cudgel against minority communities and poor communities.

As it has been legalized in more and more states across the country, it has succeeded in mostly making white people with financial backing rich. There's this big problem hovering over weed legalization and New York past this fantastically progressive law in 2021, the MRTA, that laid out these provisions that 50% of licenses would be given out to social and economic equity applicants who included women, people of color, service disabled veterans, distressed farmers, and crucially people who had lived in zip codes where police had made disproportionate arrests.

It expunged hundreds of thousands of convictions and it allocates 40% of weed tax revenue to community initiatives in those overpoliced communities. It's this fantastic law, no other state has ever done anything like it. Then it's where this meets the reality of highly advanced capitalism that things get complicated.

Brian Lehrer: Right. Listeners help Jia Tolentino report what might someday be the follow-up to this article. Are you in the legal cannabis business now in New York State, or are you trying to get into it? Talk about some of the bureaucratic hurdles, legal hurdles, financial hurdles, or if this is going well for you, report that too. First priority on the phone will go to anybody who is in or trying to get in the legal cannabis business in New York state.

The rollout being as slow as it has been, 212-433-WNYC. Other people may call with comments or questions, but if anybody happens to be listening who's in the business or trying to get into the business in New York State, in particular, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Call or text, and you'll get first priority. Further to what you were just describing, Jia, part of the idea as you write is to stave off corporate capture of this new sector of the economy. Has that happened in earlier legal states?

Jia Tolentino: I would say in almost every legal state, what often happens is that there's a medical marijuana industry that predates the adult use or recreational one. Those tend to be dominated by a handful of corporations called Multi-State Operators, MSOs, that again, are highly capitalized, tend to have zero minority ownership, but they're fully vertically integrated. They do everything from growing to the point of retail.

They have a lot of lobbying money and they successfully pressure legislators state by state to say, "Wow, weed is a mess. Let's get it out of the hands of the grubby people who were in the illegal industry and let's have nice clean corporate--" It can be a daunting thing to think about taking this industry legal and corporations have a playbook to capture it before and do what corporations are doing right now, which is corner the market with extremely low prices, and once everyone's priced out, raise them.

New York also designed its industry to stave off that capture. Vertical integration is mostly prohibited except for a very small license category called the micro business that's intended to give people many, many entry points into the supply chain, rather than give its 10 or 11 medical marijuana companies first access to the recreational market, which would've made things much quicker and more efficient, but then would've resulted in a pretty near immediate corporate capture.

They initially had a waiting period that required them to stay out at the retail point for three years. That has since changed since there has been this need to get stores open quicker because as I'm sure everyone listening to this knows there are illegal stores on basically every block of the city. New York also really admirably, commendably designed its law to try to give small business operators, farmers in upstate New York, all these people who are normally instantly shut out of the incredibly expensive, risky, high capital demands industry of legal marijuana, New York really tried to give them first shot.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, and one of the obstacles, as I understand it from your article and elsewhere, is that the state was sued by other people on the priorities list, on the social justice list, but who came in below, people with past marijuana convictions for dispensary licenses and also by others without any social justice components. They went to court too with their hopes of getting into the business. What was their claim? Why was this considered legally out of bounds to what seems like such a kind of good cause and where does that stand?

Jia Tolentino: Well, so the card program, this flagship program, where the first several hundred retail dispensary licenses would be given to people with marijuana convictions, this was not originally written in the 2021 law. It was a creation of the Office of Cannabis Management, which was created by that law. There was a little or a lot of legal room to lodge suits like this. One of them was by a group of service-disabled veterans who said, "We in the lot were supposed to get first priority. Why have you invented this new category?"

What immediately happened after that was a group of corporations were allowed to join as plaintiffs on that lawsuit. Overarchingly, what you have is a lot of interests, many of them corporate, most of them corporate, saying, "You're not allowed to shut me out, basically." New York is trying to do things differently than has ever been done, and to hold off these interests. These corporations, they have a lot of money to tie up equity programs in litigation.

This has happened elsewhere in other states. Ohio, for its medical program, designated 15% of licenses to minority-owned businesses, and that was ruled unconstitutional after a series of lawsuits. The status quo is the status quo because of things like this. Right? Anytime you try to disempower corporate money, that corporate money has a way of clawing its way back in.

Brian Lehrer: Where does this stand? You mentioned that, that person incarcerated with Anthony Weiner after a lot of frustration, a lot of obstacles that you lay out in the article. Did get his dispensary licenses. You have a great stat in there about some crazy high percentage of all the Black-owned dispensaries in America now being in New York state with even as few dispensaries are open in the state. Where does this stand?

Jia Tolentino: I think it's still early. Where it stands is that New York has more than doubled the number of Black-owned dispensaries in all of America, basically this first year of legal stores being open and still barely any stores have been opened relative to what is coming. The New York just issued its first licenses in the general round of applications. A large proportion of the licenses did go to people and social and economic equity categories.

The industry is still opening up. We're just seeing the first bloom of the legal industry, and we'll see whether or not this competition starts to put any of these illegal stores out of business. What has happened in New York is, it has been a slow rollout due to the fact that New York has just steadfastly prioritized equity. That has resulted in the industry being much slower to get on its feet than if the corporations had just come right in as quickly and efficiently as possible.

I see it as it is kind of an inevitable trade-off. If you're going to prioritize social equity in this industry, you can't have corporate efficiency. There was going to be a lag time that was going to get messy. There's going to be these lawsuits and New York is-- for now, Kathy Hochul has started to signal discontent and disapproval. There's talk about revisiting certain aspects of the 2021 law but New York is still-- the train is still running to try to do things differently than it's ever been done.

Brian Lehrer: It is a funny contradiction to think that the first priority would go to people who both had marijuana convictions and had successful business backgrounds, legal business backgrounds. How many people like that are they? As it happens, Howell Miller, who you profiled in that article, who met Anthony Weiner used to run a construction business and he had a weed conviction. He was perfectly placed at that intersection. Has that been an obstacle? Because if they want to do this sort of social justice rollout for people who've been incarcerated or otherwise convicted of marijuana offenses, not a lot of them have the business background.

Jia Tolentino: I think the CARD program is emblematic of something that I thought about a lot while I was writing this piece. Which is, it's impossible to address the harms that the war on drugs and marijuana's illegality wrought on Black and brown and poor communities with any program. Legal marijuana can't undo what decades of incarceration did. Even something as I think thoughtfully designed as the CARD program.

Like you said, how many people come out of prison with a weed conviction with all of the things that that does in terms of your housing prospects, your employment prospects, all these things? How many people are able to then mount a successful small business? The people who do, the thinking I think on OCMs part was that these people are clearly, they're scrappy, they're hustlers, they can do it.

They're utterly deserving of this first shot but of course, there are so many people who were never able to do that. There's a guy in my article who really wanted to apply for a CARD license, realized he wasn't eligible because basically he dealt weed, got convicted and that's just remained his job and so he doesn't have proof of that. I think there are even certain things because stop-and-frisk policing was so heavily directed towards men that the CARD program inevitably in trying to make up for that, effectively gave priority to men again. It's an example of how just crafting legislation to try to undo or repair even a little bit of the vast ravages of policing, it's complicated. It can never be complete.

Brian Lehrer: This is WNYC-FM HDNAM New York, WNJT-FM 88.1 FM Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcom, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are a New York and New Jersey Public Radio at 11:01 on the New York side right now as we talk with Jia Tolentino from The New Yorker about New York State's bumpy legal cannabis rolled out 212-433-WNYC. Tom in Clinton Hill, you're on WNYC. Hello, Tom.

Tom: Hey, Brian. Second time on, listen every day. I was really excited to hear y'all take up this topic today. It's a little tangential, but I'm opening a bar and last September, I went to a community board meeting in Brooklyn CB2 to get approved for my liquor license. Before they did all the liquor licenses, they handled marijuana permits and pretty much all of them got approved, but similar to what they do liquor licenses, community members can come in and protest the location.

One of them was in Prime Fort Greene just a few blocks east of the park. Someone got up to protest it and they said, "What about the schools around here, blah, blah, blah." One of the community board members, she raised her hand and said, "Hold up, hold up. There's five liquor stores within that block. If we want to talk about what the real problem is, let's talk about the liquor stores."

She just shooed away these questions about maybe weed is a problem for kids. I thought it was really interesting that they just handed out all these permits but then there's still so few actual stores in Brooklyn, legal ones.

Brian Lehrer: Tom, thank you. Interesting anecdote. We're going to talk about the illegal stores in a minute like in no other state apparently, according to Jia's article. I don't think it reported in this particular piece about sighting, that is location debates. We know that there's been opposition in Harlem to placing a dispensary on 125th Street there around the Apollo Theater. Tom mentioned it in Brooklyn, though it was shooed away in that particular case, if he's got his story right, anything on that?

Jia Tolentino: Yes. It's also almost all of Long Island. Most municipalities said no, which has resulted in one dispensary out there, Strain Stars, just absolutely crushing it in sales because people are commuting from all over Long Island. Zoning is complicated within the five boroughs, I believe that a legal dispensary has to be a 1000 feet from other dispensaries. I think perhaps the same distance from any schools, churches, et cetera. That actually points to the illegal stores they can and do or they have been allowed to and are opening wherever they want.

They're opening up right next to schools, they're opening at 8:00 AM. That should be a point in favor of these legal stores because they at least will have a much stricter set of compliance laws in terms of they will be shut down if they sell to minors. Things that the weed bodegas that are on every block are just doing whatever they want, essentially unimpeded which is a huge problem also but that I think is a point in favor of the legal stores. It's just that we don't have that many. They will be abiding by all of these zoning rules that the illegal ones currently do not abide by.

Brian Lehrer: Have you been able to get to the bottom of-- because I'll tell you, a lot of our callers, a lot of our texters are asking a version of this. Have you gotten at all to the bottom of why it's so hard to shut down these illegal dispensaries? Your description of them is really interesting. While the legal dispensaries are not allowed to show anything in the window, they can't be seeming to advertise marijuana. You have all these illegal ones that look like Apple stores with the glass windows and big leaves in the window and all of that stuff.

Jia Tolentino: Then there's the bodega, the tacky Weed Bodega model where it's just like flashing signs. It's like 420 Blaze it, Bonanza, just like weed, weed, weed, weed. One of the most incredible things about this city is that entrepreneurs will fill the tiniest crack in the market as soon as there are crack to be filled. All of the empty storefronts bloom with Mother's Day bouquets for three days only around Mother's Day or Valentine's. This is a scrappy city full of people that will fill every need, and there's a lot of real estate, a lot of empty storefronts.

If the conditions were right in that respect to allow this to happen, there was and is such a long delay between when weed was even decriminalized and then legalized for adult use and then now the legal store is opening. There's been a lot of time for these stores to open. I'm editorializing a little bit here, but it seems to me like police were basically told at some point, like, "You're not allowed to stop and frisk anymore. You're not allowed to use marijuana odor as this pretext to shake down any person or driver that you would like."

In 2020, you got this signal that the city apparently wants less policing and so now that all of these stores exist and city and state agencies are trying to or there are a lot of city and state agencies that could ostensibly have responsibility and who all should share in the responsibility of shutting these stores down but there are just so many of them and no one really wants to take the responsibility of doing it. At least the police arm, the enforcement arm, that aspect, the will is not there. The will is not there on the part of the police to do anything about it is certainly what it has seemed like to me in reporting.

Brian Lehrer: You make a pointed comparison in the piece saying, they don't seem to have any trouble busting churro ladies.

Jia Tolentino: Yes. Churro ladies. People in Corona Park selling their tamales. Cops love to bust vendors in a way that I think is pathological. Here I think there are civil and criminal violations that are occurring here. Even selling weed to minors, that's a felony. I walked around city council member Gale Brewer's district with her. We went to a store that was right across from a high school, opened at 8:00 AM, closed at 2:00 AM. There's plenty to enforce if the will to enforce existed.

Brian Lehrer: Jia Tolentino with us from the New Yorker, her latest article In The Weeds about why the bumpy rollout of legal cannabis in New York State. One more call, Pete in Brooklyn who says he has a grower's permit. Pete, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Pete: Hey Brian, real quick. The real reason the problem is really there's only 10 dispensaries in a population of 6 million people, but they gave out thousands of grower permits. Now we the growers have to get rid of our pot which we were promised that would happen. Now, we have a pot that's rotting. That's why there's these pop-up stores or whatever you want to call them. It's because we don't want to throw our pot away because it does have a shelf life. You know what I mean?

Brian Lehrer: I hear you, Pete.

Pete: It's actually really pathetic that there's only two dispensaries in all upstate New York. It just blows my mind.

Brian Lehrer: For you as--

Pete: They should have followed Oklahoma.

Brian Lehrer: What did Oklahoma do?

Pete: They just let everyone grow and they have more dispensaries than California.

Brian Lehrer: Huh? Pete, thank you very much.

Pete: [crosstalk] cards.

Brian Lehrer: We've actually talked about this on the show once before Jia, but it's almost a reason to let the illegal dispensaries keep going for a while because there are all these people who've been given growing permits, and so they've got all this legal flower, but there aren't the dispensaries open to sell it legally.

Jia Tolentino: I think a recent estimate was 250,000 pounds. Also, I will say a lot of the weed that's on the shelves at the illicit stores is very clearly marked and QR coded as California weed too. It's not as if these illicit stores are nobly selling upstate farmer's products which some of them are. Even in Oklahoma, I want to point out that is a really good comparison. Oklahoma, extremely low regulation, really low barrier to entry.

I think there was an enormous glut of supply and retail dispensaries and all of this stuff but there was so much now that the majority of the product is being diverted out of state which is illegal, and the price is plunged and a lot of the dispensaries and growing operations are now shutting down. I think this just goes to say there is no state still that has cracked this problem of how to open up a legal adult-use market that is just in any way that focuses on equity in any way and is also functional that can also compete with the black market.

That's a problem in every other legal state. In California, most weed purchases are still made in the black market. It is an ongoing thing that legislators and agencies are still experimenting with.

Brian Lehrer: That was something that surprised me from your article, that in California, which has a very well-developed legal dispensary market, the illegal marijuana market has continued to grow. How could that be?

Jia Tolentino: It's cheaper, that's for one thing. One of the reasons that the illicit stores are flourishing is because there's no compliance, they're not paying these incredibly high taxes and because of a provision called 280E, federally people who are in the legal weed business, they can't write off all of these expenses. They can't do taxes in a typical way. They can't really bank anywhere.

People often end up paying up to 80% in their effective tax rate. It's expensive to be in this business, which is one of the reasons it's dominated by white guys that have worked at Goldman Sachs. It's really expensive, it requires a lot of startup capital, and consumers if weed is cheaper at this one store, next door, to the other that they both basically look the same, can't really tell that one is legal and one's illegal, but one has 1/8 for $25 less. Consumers go to the one that's cheaper and so that's why I still like that.

Brian Lehrer: Last topic, quality, and you write about it in the article, but a listener writes, "Regarding cannabis quality, the flower is definitely weaker, though it's still much stronger than the weed your parents grew up with." This person writes, "They say, "I was told by a legal dispensary that New York cannabis is largely grown outdoors," which you report in your article. This person concludes, "three hours up the road in the Berkshires of Western Massachusetts, marijuana dispensaries are prolific and they have more sophisticated indoor growing operations, and subsequently, the cannabis is stronger as measured by the label THC percentages." Is New York weed if you have reporting on this as good a high as Massachusetts weed or California weed or any other?

Jia Tolentino: The decision to start up the growing operations by licensing outdoor upstate grows was made from this desire to establish a sustainable environmental principles because indoor weed growing can be tremendously resource intensive, et cetera. That being said, the outdoor weed stuff, people call it dad weed. Personally, perfectly fine for my taste, but if you're like a serious weed head and you want stuff that is really intense and dank and beautiful and it's very very sticky and all really loud, all of these things. Dad weed, outdoor weed is not that.

That being said, now that New York has opened up grow licenses to indoor grow this year there are micro businesses that are going to be allowed to grow indoors. Some of them are legacy growers like this one guy, the collector, that I interviewed in my article, people that do grow weed for weed heads. Like, it'll be strong, it'll be potent, it'll be very dank. That stuff is starting to get grown in New York.

Brian Lehrer: Soon you may be able to buy it in more places. The article is called In The Weeds.

Jia Tolentino: Hopefully.

Brian Lehrer: Jia Tolentino is a staff writer for The New Yorker. Jia, thanks so much.

Jia Tolentino: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.