The New Yorker's Women Cartoonists

( by Liza Donnelly / Prometheus Books )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Which comes first for you when you get this week's New Yorker, the deep dives into essential issues, the cutting edge short stories, or the cartoons? Did you know that the cartoons came first, literally? I think I'm using the word literally right? Where's The New Yorker copy editor when I need one. The New Yorker started as a humor magazine back in 1925. Cartoons were part of that and women cartoonists were a part of it, too.

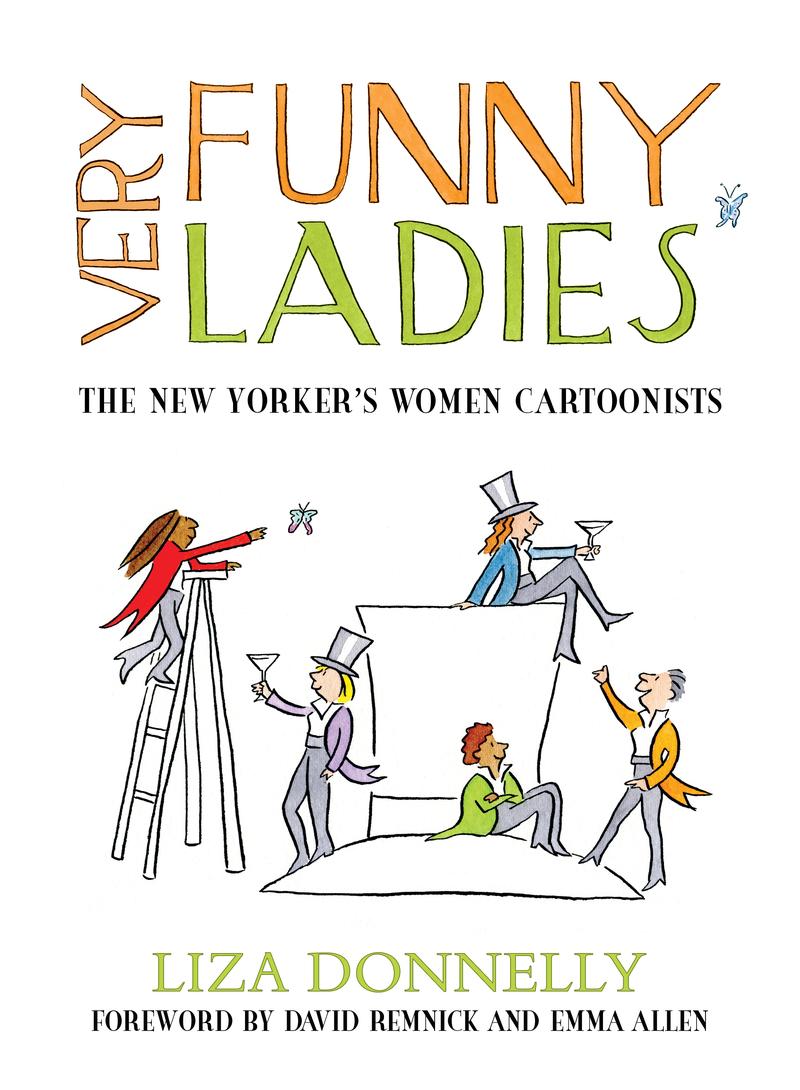

It took until 2017 before women outnumbered men in a single issue. In the post-World War II years, their cartoons were few and far between. We'll talk about why. My guest Liza Donnelly, a longtime New Yorker cartoonist has a new book that examines that history and the lives of the women who made us laugh, or at least smile broadly. Her latest book is Very Funny Ladies: The New Yorker's Women Cartoonists, 1925-2021. Hi, Liza. Thanks for coming on with us. Welcome back, and congratulations on the book.

Liza Donnelly: Oh, thank you, Brian. Thanks for having me. It's great to be back.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if you want to follow along, Liza has shared a few of the cartoons from the book with us. We've posted them on our website @wnyc.org. Just click on Brian Lehrer Show, or you can go right there these days @brianlehrershow.org, and then you'll click on the headline for this segment to see them.

Let's talk about the first cartoon by a woman Ethel Plummer in 1925. It's a man and his niece, a young woman identified as a flapper reacting to a poster. The poster had the headline, The Wages of Sin, and the man says, "Poor girls, so few get their wages." She says, "So few get their sin, darn it." [laughs] Why don't you just talk about that cartoon in the context of 1925 in The New Yorker?

Liza Donnelly: Well, in my experience from 1925, no. This actually was in the first issue of the first New Yorker so that's remarkable. I was surprised to find that and I'm happy to find that. I feel like the woman represents many women in that time in New York, at least, very flapper era, very wanting to do what they want, drink alcohol and smoke cigarettes and dance until 3:00 in the morning. I think that's what she's wanting to do, and he's more concerned about money. That's how I read it. How do you read it?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that way. I guess the '20s were a time of changes to women's lives and place in society, shorter hair, shorter skirts, the vote. Maybe that's where a lot of the early women cartoonists focused.

Liza Donnelly: Yes and no. I think that they drew about what it was like to be a woman in that time. Many of them drew like Barbara Sherman is my favorite from that period. She frequently drew about young women and trying to navigate urban New York. The New Yorker was founded as a humor magazine, as you said, and it was Harold Ross and Jane Grant, who founded the magazine.

They were married. She actually, interestingly, she was a city reporter for The New York Times, which is unusual. She was an activist feminist. They started the magazine together. She didn't stay around to run the magazine but Harold Ross did. They wanted to do it like a new kind of humor, a very hip, and although they didn't use that word back then, in the moment, humor for the urban elite.

From the beginning, it was directed towards a certain demographic, and many of the women-- They were looking for the best artist of the time in New York, and many of them are women because women like in many professions were flooding the urban areas to look for work following the, as you said, the gain on suffrage. Women of a certain demographic, of course.

Brian Lehrer: Another woman who started in that era and stayed with it, I think for a good while was Helen Hokinson. You have two cartoons from her for us. The first one harkening to the theme of her later works that show how things change for women over time. Would you like to describe that?

Liza Donnelly: Oh, I don't have it up on my screen.

Brian Lehrer: It looks to me like it's a cartoon without a caption.

Liza Donnelly: Oh, yes, I see it.

Brian Lehrer: Two women reading things.

Liza Donnelly: Yes. Two women circling what looks like a brand koozie sculpture and they've got their museum and they've got their programs, the museum explanation of the artwork, and they circling it like it's an unknown object. I think that was from the 1920s, actually. I think it was her first cartoon in the magazine. She became very very famous, very well known in her time.

Brian Lehrer: Then there's another one, it looks like two women from her-- two women having a conversation. One of them or both of them might be smoking a cigarette if I'm seeing this right. One of them says, "You know, it don't seem right--" This is the print on it, it printed on my printer it's so small. If you have it, why don't you read that up?

Liza Donnelly: I can read it. "You know, it doesn't seem right to take presents from a man you ain't engaged to. I guess I'm just an old-fashioned girl."

Brian Lehrer: Why would people laugh at that?

Liza Donnelly: [chuckles] Good question. That it's just talking about the times that women were trying to figure out how to be modern, but still follow the rules that were prescribed for society. You don't take presents from a man you ain't engaged to, I guess, in the '20s. That's why they would laugh at her. I think that's why because it's like a juxtaposition of opposite that people trying to figure out how to get along in the world. I would suppose many women related to that.

Brian Lehrer: The women in that cartoon was like you were describing before, young, urban, fashionable women, but maybe some current New Yorker readers remember Helen Hokinson's large middle-aged ladies that became her trademark. Do you think that shift for her was because she herself felt confused by more contemporary youth culture?

Liza Donnelly: It's a really interesting thing to think about with her and the way her work changed, and what made it change. It was always beautifully drawn and funny, she was always very funny. She actually did not write her own caption, she worked with a writer, a regular. In the early days, she worked with editors, but then she found a man that she really enjoyed working with, and they wrote them together. Her drawings themselves were always funny to look at, and particularly the matronly ladies that she's so well known for.

Many of them are on the cover of the magazine. I think my sense of it, Brian is that she was drawing the times in the '20s and '30s, she was drawing these young women. Then as she began to draw these matronly ladies making fun of them overweight women, many of them befuddled but trying their best to get along in the world, that character that she drew became more popular. The editors published that more often.

More people could relate to those heavyset women, I guess than to flappers. She drew more and more of those women. I think she said that she was trying to lovingly make fun of the women she saw around her in Connecticut because by then she had moved up to Connecticut, was not living in the city. That also probably, she was making fun of the lunch ladies, the ladies who go to the garden club and things like that. That was her take on her world around her at the time.

Brian Lehrer: Can you as a cartoonist talk about that relationship between what you draw and the lines that you or someone else write as captions? It's hard for me to imagine, I've never been a cartoonist, but it's hard for me to imagine, well, which comes first? Does somebody come up with a line and a concept for the cartoon, and then she would draw it, like in the case you were just describing, or it would be harder if somebody comes up with a funny image to put a caption on it? Of course, The New Yorker has its cartoon caption contest. Which comes first?

Liza Donnelly: For me, Brian, it's a mixture of both. I write my own ideas. I draw stuff, and then sometimes a cartoon comes out of that, but sometimes words come first or a buzzword or a thing that's being talked about in the culture. I did a number of cartoons like the war on women, I did a cartoon about that, or [unintelligible 00:09:42] I did a cartoon about that. Sometimes it's a combination of words and images. In Helen Hokinson's case, my understanding is that she worked with James Reid Parker, intimately. It's not like he gave her a line and she illustrated it. It was more like she would come up with a drawing and then they would talk about it, and maybe he'd come up with the caption. It

was a very collaborative relationship. There are cartoonists who use we call them gags, a word that I'm not fond of, but gag writers. They became very much a thing in the '50s. Because the cartoons were so successful, writers came in and they wanted to be a part of it and cartoonists, some of them lost their muse, and they were tired of writing captions, so they would hire these gag writers to write for them.

Also, this is an interesting little tidbit. When I started in the '70s, many of the young cartoonists that I was friends with Mick Stevens and Jack Ziegler and I don't know if it's true with Jack, but many times these cartoonists would be brought into the fold by having their ideas bought. They would submit cartoons on a weekly basis with the caption and the drawing of their own.

Then the New Yorker would say, "We'd like to buy this for whomever," a more established artist like Charles Addams would use other people's ideas, Whitney Darrow Jr. That's how young cartoonists would be brought into the magazine. That didn't happen to me. It didn't happen to Roz, I know that for sure. Roz Chast, but many of them did.

Brian Lehrer: You have a Roz Chast in here for us to post on our site and talk about it with you. She got her start in the late '70s, the great Roz Chast. We have one of her images that is also, well, its captionless, but then again, there's a woman looking at a statue and the statue has an inscription. Do you want to describe this one?

Liza Donnelly: Sure. A woman is walking by a typical statue in a park of a woman standing with a briefcase and it says Doris Kay Elston, brain surgeon, professional model, artist, lawyer, plus mother of four. I don't have the date on this cartoon, but I know it's probably from the '80s. It's not modern. Maybe it still speaks to some people. It was like a time-- I remember the '80s women were trying to have it all. They were trying to do everything and we were feeling that we needed to do everything. The pressure was there for women, and that's why we laugh at it, I think.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. She's now the quintessential New Yorker cartoonist, maybe but some readers weren't convinced at first about Roz Chast. Is that part of your history?

Liza Donnelly: That's true. This is a fairly traditional-looking cartoon of hers, but sometimes her work is very different. It's not different now because she's set her style in stone and she's very popular. Everybody loves her as they should, but back in the late '70s, early '80s, her work was much more unusual, and I can't think of the word like oblique. It was like your--

I have a good story that I think she's told many times is that when Lila [unintelligible 00:13:08] who was the cartoon editor who brought her in, in the '70s, he brought her work up to William Sean, who was the senior editor then. William Sean says to Lila, "How does she know they're funny?" Or, "How do we know they're funny?" I don't remember the exact quote, but that's the way they were and many of the cartoonists didn't-- many of the older cartoons were a little perplexed by Roz.

Brian Lehrer: My guest for another few minutes is Liza Donnelly, a longtime New Yorker cartoonist. The author now of a Very Funny ladies: The New Yorkers Women Cartoonists 1925 to 2021. We have one of yours. It's the New York City skyline with a rooftop party happening on top of an apartment building and the hostess says, "Okay, everybody. Let's see before the food gets dirty life in the big city."

Liza Donnelly: Yes. That could apply to any city I suppose, any big city.

Brian Lehrer: It's self-explanatory. Is there anything you want to say about it?

Liza Donnelly: [unintelligible 00:14:11] you can see the date of this cartoon because the Twin Towers are background so this is done in [crosstalk].

Brian Lehrer: Yes. In your own work, do you see anything essentially female about it since you focus for the book on women cartoonists of the New Yorker?

Liza Donnelly: No, I don't. I don't like to think that way, Brian. It's more that women draw cartoons. When I started out as a child drawing cartoons, I didn't think about gender. I never thought of myself as a woman cartoonist, but as cartoonist having to be a woman and I still do. The reason why I did this book is to try to shine a light on the fact that we are here and we weren't here for quite some time, as humorous, and then we all draw differently. There's no female perspective. There's just people who are drawing funny things that are cartoonists.

I wanted to mention with Roz and some other cartoonists that the voice that they have is very much their voice and you know that with Roz. You just know it-- you look for her work and you love it and you eat it up. Charles Addams is the same way. That's what I loved about the New Yorker when I first discovered this young woman, is that they treat the humor as a view, an artist's view. Cartoonists, many of us don't call ourselves artists, but we are. It's about our take on the world, our take on humor or our neuroses, or our worries. That's what I love about New Yorker cartoons. I just think-

Brian Lehrer: No, no, go ahead. Did you want to finish your point?

Liza Donnelly: Well, the diversity, now that the New Yorker is the cartoon community is so much more diverse than it was, still have a lot of work to do.[unintelligible 00:16:04] the new cartoon editor and David Remnick have worked very hard to increase the diversity among the cartoonists' community.

They're being successful as you witness. There's more women and there's more people of color, more people of different backgrounds. We have transgender cartoonists and non-binary cartoonists. It's great to hear from everybody, all the different worlds, all the different approaches to the world for humor is what the New Yorker is handing us.

Brian Lehrer: We will have to leave it there. Liza Donnelly's book is Very Funny Ladies: The New Yorker's Greatest Women Cartoonists 1925 to 2021. You can hear more about the book this Friday, when she'll be speaking at the 92nd Street Y and how fun is this good to be joined by fellow cartoonists Roz Chast, Amy Hwang, and Emily Flake. That's at seven o'clock Friday night, and you can find ticket information on our website, or at 92y.org, their website. Looking forward to that?

Liza Donnelly: Yes, me too. I can't wait. It'll be fun. We'll have a lot of laughs.

Brian Lehrer: Liza, thanks for coming on.

Liza Donnelly: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: That's The Brian Lehrer Show for today. The Brian Lehrer Show is produced by Mary Croke, Lisa Allison, Zoe Azulay, Amina Srna, and Carl Boisrond. Our interns this spring semester are Anna Conkling, Gigi Steckel, and Diego Munhoz. Zach Gottehrer-Cohen edits our national politics podcast. Tell your friends around the country to subscribe. Meg Ryan holds it all together with scotch tape and glue if necessary, with a stapler gun if need be, with diplomacy and tact strategically applied as the head of live radio. That was Juliana Fonda at the audio controls. I'm Brian Lehrer.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.