New York City's School Buildings Shutdown (Again)

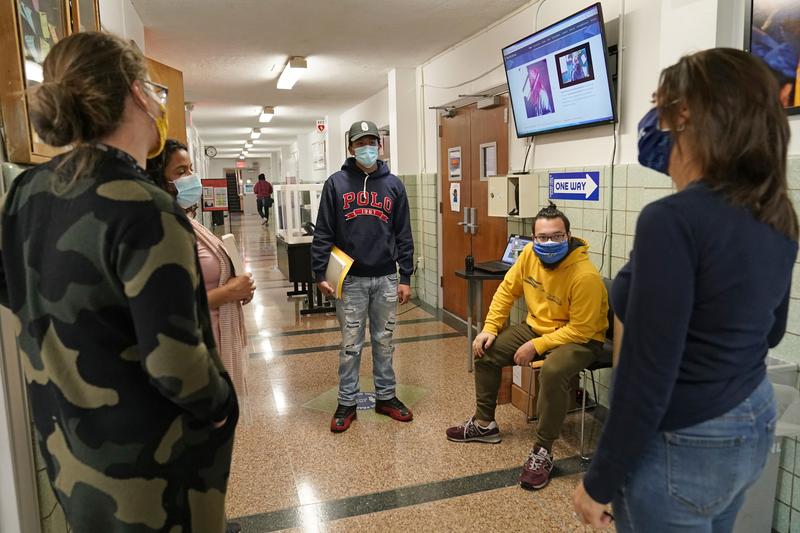

( Kathy Willens / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. New York City schools return to all-remote starting today as you know. This as the city's COVID-19 case count and positivity rate keeps rising, hitting the 3% testing positivity seven-day average threshold. No matter whether you support or oppose the decision, what a nightmare getting there, and at very least a bad luck for Governor Cuomo in the way he handled it in public yesterday. We'll play a clip and explain.

Joining me now are Jessica Gould, WNYC education reporter, and Brigid Bergin, City Hall and politics reporter for WNYC. Welcome back to the show, Jessica and Brigid.

Jessica Gould: Hey, there.

Brigid Bergin: Thanks, Brian.

Brian: Jessica, yesterday, at Mayor de Blasio's news conference, he and Schools Chancellor Carranza said the schools will be closed starting today, and at least through Thanksgiving. Some news reports were saying, schools are closed "indefinitely". What do we actually know about the timeline? I know parents are wondering how long is this going to last?

Jessica: Well, Mayor de Blasio says he wants to make this as short as possible and he keeps saying it's temporary. He did say that the earliest that schools could come back would be the week after Thanksgiving, but he wasn't making a commitment to that. He has to figure out new standards for reopening the schools, which he said he was working on starting now with state stakeholders, with the unions. He did say today that we would have information about what those reopening standards are within the next few days, so we'll be waiting for that.

Brian: Meaning it could be 3% positivity rate on the way up, but 4% or 5% positivity rate on the way down?

Jessica: Yes, I think that there are a lot of different ways this could go, and maybe Brigid can talk about this as well, but Governor Cuomo was talking about micro clusters yesterday as part of that very heated press conference. The way that schools in those micro clusters in Brooklyn and Queens came back was that he said they could eventually come back if they had testing and more testing, weekly testing, and students were tested before they came back to school.

We do know that testing is going to be a huge part of whatever the reopening plan is and my colleague at Gothamist, David Cruz, and I did some searching over the past few days and found out that more than half of families haven't submitted their consent forms to get their kids tested. Even though the infection rate as it shows in schools is really low right now, there also aren't as many students being tested as you would want to have a robust sense of what's going on in the schools.

Brian: Brigid, there was a lot of confusion yesterday. In our newsroom, a lot of us were talking behind the scenes with each other and among parents as the city waited to hear from Mayor de Blasio on the status of school closures, as the mayor was supposed to speak at 10 o'clock in the morning, but kept delaying it. Then it turned out the first person to come out to speak, around I think 1:30 in the afternoon, was the governor and people didn't know what was going to happen.

People didn't know if the schools were going to be closed yet, but it was hard to get a straight answer from the governor on that. Here's an exchange between the governor and Wall Street Journal reporter, Jimmy Vielkind on whether the governor would overrule any decision by Mayor de Blasio to close the school.

Cuomo: What are you talking about? What are you talking about? "You're now going to override--" We did it already. That's the law. An orange zone and the Red zone. Follow the facts.

Jimmy Vielkind: I'm just still confused.

Cuomo: Well, then you're confused.

Jimmy: I'm confused and parents are still confused as well. The schools [inaudible 00:04:17].

Cuomo: No, they’re not confused. You’re confused.

Jimmy: No, I think parents are confused as well.

Cuomo: Read the law and you won't be confused.

Brian: Brigid, I think we could say as a matter of journalistic reporting without much digging, the parents were confused at that moment when the governor was saying that parents weren't confused.

Brigid: Oh, absolutely. I think parents were confused, educators were confused, state leaders, local leaders, and reporters were all confused, because there were a couple of different things going on when that press conference was happening. It echoed things that I think we have all experienced over these past eight months. Instead of having city and state leaders coming together to make this hugely consequential announcement that will impact the lives of millions of New Yorkers, they had to parse these seemingly conflicting messages from Governor Cuomo and then later Mayor de Blasio.

What we know is that there were lots of conversations happening yesterday between them and education union leaders. Those conversations delayed the mayor's briefing by, as you said, a good five hours. It was supposed to happen before the governors. What we heard just in that clip there was the governor essentially scolding Jimmy Vielkind for asking what was a completely clear and fair question, that we later learned from the mayor that the governor actually clearly knew the answer to.

He knew that the city had reached its 3% positivity threshold. The reason it became increasingly confusing is because during the governor's briefing, he was indicating that the city's positivity rate was only at 2.5%. One of the things that has muddled some of these decisions over the past few months is that the city and state have been reporting different numbers because they use different methodologies to calculate their positivity rates.

I think it was very fair and very reasonable for both the Jimmy Vilelkind then later The New York Times, reporter Jessie McKinley and others to press the governor on this question, because one of the things we have also seen is the mayor attempt to roll out a policy to only then, shortly thereafter, have the governor come in and come up with his own version, calling it either by a different name, whether it's the pause or, just laying out new parameters changing closures from zip codes to zones. That's been something that I think has really been frustrating to both report on and certainly for New Yorkers to live with.

Brian: Now, as we open up the phones, usually when school is in session we say, if we're doing this kind of a topic, parents happy to have you call in, teachers, we know you're working. Maybe a few of you are on prep periods and you can call in, but mostly parents are available, teachers are not. Today it might be reversed because a lot of parents whose kids were in in-person school are having to supervise them as they do remote learning and teachers are suddenly at home, not that you're not working, you're teaching remotely. I get that. Maybe more teachers are available to listen at a given time than when you're going into your school buildings.

Teachers, do you like this? You know there's a lot of reporting that, or at least speculation, that the only reason the mayor closed the schools today was because of pressure from the teachers union. Do you want him to be doing this for your safety? If so, how would you respond to the case positivity rate which has been so low in the public schools, way under 1%?

Parents and anyone else who a stakeholder, call in and make your voice heard or ask our reporters Jessica Gould and Brigid Bergon, a question (646)-435-7280, (646)-435-7280. Jessica, does the teachers union support the temporary closure, and to the extent that it can be fact-checked, is that the reason the mayor is doing it?

Jessica: Well, they definitely support it and we know that they were in conversation. The union president was in conversation, Michael Mulgrew, with the mayor and the governor yesterday. A lot of teachers were in favor of this threshold because they have concerns about safety, they have concerns about the delay closing schools in the spring. But a lot of teachers and administrators are not happy with this decision as well, because they feel like it's disruptive for students. It's really hard to engage them online. They get energy and joy from being in classrooms in-person with kids. Remote learning, just isn't the same.

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Desiree in Park Slope, you're on WNYC. Hi, Desiree, thanks for calling.

Desiree: Thank you for having me. A couple of things. One, nobody is doing what they want to do right now. People working from home don't necessarily enjoy working from home and it's definitely not always better than working in an office. I think that that's the wrong factor to measure things on. We know that teaching kids at home is not the same as teaching them at school, but we're not living in a time that is the same. That's first thing.

Second thing, children don't only live in the school. It's not like they teleport from their house to the school. They'd ride the bus. They read the subway. They're gathered in groups after school, they're walking the streets with their masks off and teenagers are just as equipped at passing the virus on to adults as vice versa. I feel like the emphasis on what is happening inside the actual school, where not everybody's being tested is the wrong emphasis because New York City children live in the world. It's not like in the suburbs where you put your kid in the car and drive them to school and they go interact with anybody else.

Whether or not there is a high status of positive readings in the school, the kids are in the world, just like us. They're in the store with me, they're in the park with me. Do you see what I'm saying? The other thing is I haven't heard any emphasis by the city or by the parents about how to improve remote learning. Like it's the 21st century. We have all kinds of technology. Everyone is so focused on wanting kids to be in school and on site, that they're not putting any effort into actually making the experience of learning remotely better.

Brian: Great points, Desiree. Thank you. Let me throw each of those to our two reporters. Brigid, first on the first one, yes, what happens in school doesn't necessarily stay in school. Even if there's a low transmission rate within the schools, whoever's getting it in the schools then goes out and walks around. I know there's an argument on the other side. In fact, we'll be talking in our next segment to the Nassau County Executive Laura Curran who doesn't like that Mayor de Blasio closed the schools in New York City. She's not doing that in Nassau.

To the caller's point about what happens in the suburbs, well, even in the suburbs, even if the kids are not in school or if they are in school, after school they're congregating in people's houses and they're congregating outside and that's how the virus is apparently being spread to some meaningful degree in the suburbs. Nevertheless, there's an argument for keeping the schools closed.

Brigid: Absolutely. I think that there's no perfect scenario and no perfect policy right now. I think part of what we heard, that also contributed to muddling some of the communication yesterday, was there was a very, very clear signal from the governor's briefing that he was suggesting that, the whole of New York City could become an orange zone that could lead to additional closures.

Again, just this morning, some of the initial comments from Mayor de Blasio in his early briefing, suggesting that things like indoor dining and gyms, and some of these places that folks look at and say, "Well, how are they still, if we're shutting down schools?" Well, we are clearly on a path that they may not be open a whole lot longer. I think at this point, there was a-- to your earlier point, there was an agreement between the teachers union and the city, a plan was submitted to the state setting this 3% standard for shutting down the system.

I asked the mayor this question exactly a week ago, because we were creeping towards that 3% threshold. At that point, we were starting to see more targeted shutdowns. A version of Cuomo's micro cluster strategy, where instead of trying to do something across an entire Borough, perhaps you do just something within a certain block radius, depending on the numbers of the positivity rate in that targeted area.

The mayor was very firm. That 3% was an agreement that they established. It was a commitment they'd made to teachers, to parents that they needed to follow through on that. At the same rate, what is also clear is as they look at the reopening, they also are looking at what the science is telling them. Chancellor Carranza, just yesterday during the briefing where they're telling parents and educators that they're closing things, noted that the positivity rate within schools was just 0.19%. You see, they need to do some re-examining of their standards and some of their protocols

Brian: To the caller's other question, Jessica, for you as an education reporter, are they centering remote learning in ways that they weren't in the spring to try to make it as good as possible? I hear that complaint from caller after caller after caller.

Jessica: Yes. I think you and I have been talking about this since the summer, which was seen as this lost opportunity to work on remote learning and all the resources that were poured into opening schools, which now have been open two months before going all remote again. Maybe more of that emphasis should have been placed on remote learning and improving remote learning. Teachers have been hungry for support and how to do it.

As you know, because you've asked the mayor this multiple times, when asked what can be done to improve remote learning, he often pivots to remote learning is just not as good as in-person and that's why we're so committed to in-person learning. I think that there's a lot of frustration among teachers and parents and kids. I've been hearing from a lot of kids who are complaining about remote learning. They're not as motivated to show up for their remote classes, which is a big concern. They glaze over with screens. It's really too bad that more hasn't been done to focus in on this, especially because we know that there's some teachers and some schools who are making it work better.

Brian: Dexter in Brooklyn, a substitute teacher, you're on WNYC. Hi, Dexter.

Dexter: Hi. How are you doing? Yes. One of the questions that I have that I'm most concerned about is, if with the closure of the schools, will they reinstitute the REC systems. I know there was the Learning Bridges program that's supposed to be a successful program, the REC program in the past during the first phase of the shutdown earlier in the year, but the program that they have now, the Learning Bridges program, from what I'm hearing from some of the parents that I've dealt with, is there's a long waitlist to get students in and it's now being run by Parks and Recreation. There are no educators in that setting. I imagine that would only make an already the challenging situation worse.

Brian: Jessica, you want to take that?

Jessica: Yes. I can take that one. I don't know about Parks and Rec. That's not my understanding that they're running it. I do think that the DOE is partnering with some nonprofits and community-based organizations on some of the Learning Bridges. There does seem to be a problem with spots getting to people where they need it, because the mayor said yesterday that there's vacancies in Learning Bridges, that there are spots available. People haven't participated as much as he thought they would and yet we've been hearing from callers on your show that they're on waitlists or they can't get in.

My understanding is that there are some areas that are oversubscribed and then some areas of the city that are undersubscribed. There needs to be some reorientation with that. Right now Learning Bridges has 40,000 seats available I believe, I think the mayor had originally said he was aiming for 100,000, but this will be open for the kids of essential workers. The mayor said today that if you want a spot in Learning Bridges, you can call 311 and learn more about where a site might be near where you live.

Brian: Does that mean that almost anybody can choose to opt in, even though they're closing the schools. I know one family in Brooklyn, for example, where they just got a Learning Bridges spot. I don't think either of the parents is an "essential worker" under the usual definitions, but the spot is miles from their house and they don't even feel like it's usable for them.

Jessica: Right. That's what I've been hearing too, is that there are spots available, but it's dependent upon your school's relationship with the Learning Bridges site. I've heard from the people who've gotten spots that they're actually really happy with the experience, but getting those spots it's so frustrating that there are vacancies in some places and yet people who need it can't get in. We're going to be watching that. I know that our colleagues at Gothamist are going to be pursuing that today. There was actually a council hearing on Learning Bridges and how well it was working or not yesterday, but nobody could watch it because everybody was waiting to find out what the governor and the mayor were going to say.

Brian: Ray, in Harlem, you're on WNYC. Hi, Ray.

Ray: Hi. How are you?

Brian: Good. Your wife is a teacher, I see?

Ray: Yes. She teaches at [unintelligible 00:19:28] in the village and I've called you before about this. First, I want to challenge them on the testing a little bit. I don't know about other schools, but when they came to my wife's school to test, they tested very few of the children. I think out of her classroom, maybe one or two kids got tested because the permission slip, they downloaded from the board of ed, what they were told with incorrect, or the principal even showed up with a couple of kids. They said, "Well, but kids not in our system. So we can't test them." I have to question what their numbers are if it's like that in every school.

The biggest complaint is that my wife is basically working twice as hard because she has to now plan like over the weekend, she was planning to be in school and she was also planning to be out of school. For instance, yesterday they didn't know until 2:15 that they weren't going to be here today. Some of the teachers were literally on the path train back to New Jersey and had to turn around and come back or pick up their stuff to take home.

They got absolutely no training or support in remote learning and the many months that they were off. They're just flying by the seat of their pants, trying to figure out how to make that better. The board, they just wasted a lot of time, they could have made that better option.

Brian: Yes. Can I ask if your wife as a public school teacher was happy about this closure?

Ray: She wasn't necessarily happy or unhappy. She's much happier being in school and I think she feels a little safer than she did at the beginning of the year. She's more upset that they just won't make a decision one way or another and get them the support to make that decision work. I feel better that she's not going into school for our health and our family, but her mental health is certainly better when she's in school.

Brian: Very interesting, Ray, thank you very much. Jessica and Brigid, as we start to run out of time, there are race and class issues here, disparity issues as with everything. Chancellor Carranza said during the press conference yesterday that 60,000 students still don't have the basic equipment to work from home. We know those families are disproportionately non-white and disproportionately lower-income. 60,000 students without the basic equipment to learn at home this far into the pandemic. I am baffled by that.

Jessica: I agree. I asked when those 60,000 devices are going to be delivered? I was told by DOE this morning, days, and weeks from now. They say there's been an international shortage of devices because of everybody going remote. Yes, that's completely unacceptable and the Wi-Fi situation, which I'm hearing is actually even more of a problem for more students, is also unacceptable.

Brian: To finish it up, Brigid, on the politics. To some degree, I feel like there's always going to be outrage and the outrage is always going to be centered in the media no matter which decision gets made by the mayor or some other officials. There was such a drum beat in the late summer when the mayor wanted to open up the schools. People calling in, people writing off beds, everything, "What do you mean you're going to open up the schools? LA isn't opening up the schools. Boston isn't opening up the school. Chicago--" Now that they're closing the schools that drum beat, "What do you mean you're going to close the schools in these close call difficult situations."

Brigid: Absolutely. You hear some of that coming from certainly the mayor's press office highlighting that dissonance saying, "When we were trying to open, there were complaints from folks about the opening. Now that we are following through on the commitment we made for when we would close them, there's complaints about the closure." I think the challenge here, and it's a challenge that has persisted throughout the pandemic, is that this is a virus that presents so many unknowns. As we learn more about it, we have to adapt.

One of the criticisms of this particular decision was, it is a threshold that was established back in the summer. He announced it in July and since the schools have opened and the science suggests that schools may not be in fact the most dangerous place for kids and for people to be for spreading the virus that potentially they should have rethought this and shown a little bit more flexibility around this metric. That may in fact inform how they decide to reopen.

But it opens the door for criticism and some of those critiques we were hearing, even from people seeking to succeed the mayor. People who are campaigning for the position at 2021 mayoral races. You know, Brian, you had Brooklyn Borough President Eric Adams on yesterday. I talked to him about this issue because I spoke to him after the mayor and the governor made their announcement. He was very critical of both the decision to close schools, the adherence to this 3% threshold that he said the science suggests maybe is too stringent, but most importantly, the fact that the two of these leaders over a seven month period of time still cannot seem to sit down in a room together and deliver consistent information to New Yorkers here in the city and across the state. That's a real source of frustration.

Brian: WNYC City Hall and politics reporter Brigid Bergin. WNYC education reporter Jessica Gould. Thank you both. Keep it up.

Jessica: Thank you.

Brigid: Thanks.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.