New Rules To Let More People Donate Blood

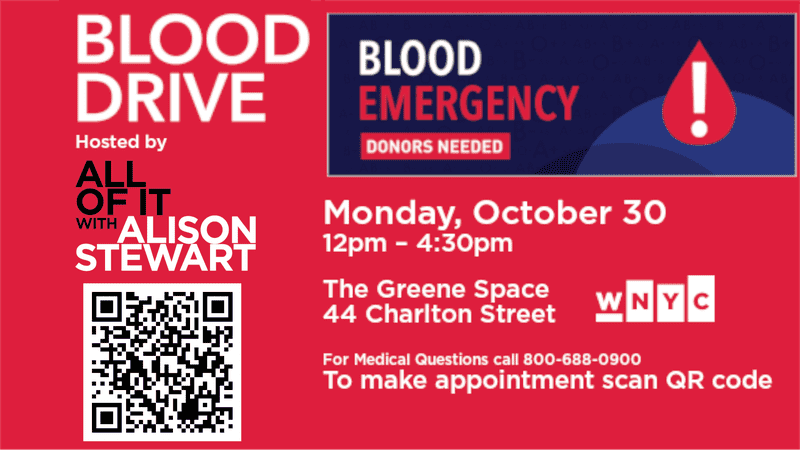

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. We want to draw attention out of something really admirable that my colleague Alison Stewart and her team at All Of It are doing. The show is celebrating its fifth anniversary now, and rather than just have a party and cake and pat themselves on the back, Alison and Company are staging a blood drive right on the premises at WNYC. It's this Monday, October 30th.

As listeners and employees here at the station will donate much-needed blood in a time where the country is facing a shortage. I don't know if you've heard news stories about the blood shortage in America right now. It doesn't get as much coverage as probably it should. I will say that most of the slots for Monday are filled. I urge you to see if you can sign up because there are some open last I looked at wnyc.org/giveblood.

Even if you can't participate at WNYC in person, you can give blood any time, of course, in multiple locations around the city. The other reason for this as their anniversary celebration and another reason to love Alison, as many of you do already know, is that Alison bravely donated a kidney this year to her sister, and through that process, she says she learned that she has a rare blood type. After getting used to the needles and the prodding that was involved in kidney donation, she resolved to promote the idea of giving blood.

We want to take these few minutes on this show to amplify the good deed that they're doing over it there. If you've never donated blood before, we know it can be a scary prospect. What we're going to do now is take a few minutes in Alison and the blood drive's honor to talk about how it works and the situation in our healthcare system that doesn't get much press. We're very happy to have with us now, Dr. Bruce Sachais, Chief Medical Officer for the New York Blood Center. Thanks so much for coming on Dr. Sachais and for your work. Welcome to WNYC.

Bruce Sachais: Thanks, Brian. Thanks for having me and thank you and your colleagues for hosting a blood drive. Really appreciate that.

Brian Lehrer: I see that last month the Red Cross declared a national blood shortage here in the United States. What does that mean and how do you measure it?

Bruce Sachais: A blood shortage means we do not have enough blood typically to sustain us for the number of days that makes us comfortable. In an ideal world, we would have five to seven days of blood on the shelf for everyone who may need it. Typically in an emergency, it's down to two days or even one day's worth of some of the more critical types of blood, like O positive and O negative. What that means is if there's a large number of patients larger than anticipated that need blood on a day, we may not have enough to go around in hospitals, then have to decide how to distribute that blood.

Brian Lehrer: We'll talk about those blood types in a minute. Who gets blood donations? Who needs them the most? Are there certain people with certain conditions for whom blood donations are the most critical and where most of the blood winds up going?

Bruce Sachais: Absolutely. Although many hospitalized patients at some point or another do end up needing blood, cancer patients are probably at the top of the list for getting the most amount of blood because they need not only sometimes acute blood during their treatment, but also more chronically as they're recovering from chemotherapy and/or other treatments that they get [unintelligible 00:03:43] bone marrow transplants can take quite a while for that to kick in.

There could be weeks where they're transfusion-dependent. Another big population would be trauma patients. Any of us can become a trauma patient unfortunately at any moment. They can take large amounts of blood up to dozens and even more from an individual trauma situation. Then also there are patients with chronic anemia who only need a little bit of blood for transfusion event but can need blood for years.

Brian Lehrer: Let's talk about the different blood types. I think a lot of people do know, but a lot of people don't know what their own blood type is. You want to give us a 101 very brief reminder about the different blood types and how they're used and what Alison might have meant. I don't know if we want to reveal her blood type or not. Saying she has a rare blood type, are there rare blood types and common blood types?

Bruce Sachais: Absolutely. Most of us know about A and B and ABO, so we can have molecules on our red cells called sugars. They can be an A configuration, a B configuration. You could have both and you could be AB or you could have neither and we call that O. There's also a protein called RH, specifically RHD. If you don't have RHD, you're RH negative. The problem that we face on a regular basis, or the challenge I should say, is that there's certain compatibilities with making sure that your blood type you get the right types of transfusions, either of red blood cells or of the liquid part of your blood, the plasma has to match so that we don't have any damage or destruction of the red cells that we're putting in. We also don't want to damage the red cells that your body is making.

Brian Lehrer: I see the Red Cross notes that there's an increased demand for those with type O blood as well as platelet donations. Why is type O blood needed in particular right now?

Bruce Sachais: In New York Blood Center also is looking for those types of blood. O can be given to pretty much anyone if we need red cells. That's a universal donor type. Especially O negative because then people who are RH or negative are able to get that. If they get positive, especially women of childbearing age there are antibodies that they can make, which could cause problems down the road with pregnancy. We try to avoid that.

If we don't know your blood type in an emergency, we want to give you at least O blood, if not O-negative blood. There are some other situations too, for example, sickle cell patients where oftentimes because of other types of things we need to match on red cells, that we will use O cells especially early on for those patients. The bottom line is there are more need for O transfusions than there are O donors. To combat that we try to specifically target people who are O but we often don't make up the difference.

Brian Lehrer: If you're just joining us, we're talking with Dr. Bruce Sachais, Chief Medical Officer for the New York Blood Center. There is a blood shortage in the New York area and nationally. We're celebrating and amplifying our colleague Alison Stewart and her show All Of It is celebrating their fifth anniversary. Coming out of the kidney donation that Alison just made to her sister, instead of a fifth-anniversary party for the show, they're having a blood drive at the station on Monday.

You can try to sign up though most of the slots are taken, maybe all the slots are taken by now, but they're encouraging you to give blood wherever is convenient for you in honor of their fifth anniversary. What an amazing good deed Alison is doing to celebrate the fifth anniversary of All Of It. Dr. Sachais, even in blood donation there are some politics and questions of fairness and equal treatment.

We know that the spread of sexually transmitted diseases and infections is a fear with regard to blood transfusions and that those have resulted in regulations around who can give blood. Some of the history here for people who don't know it, back in 1983, the FDA implemented a lifetime ban on blood donations from gay and bisexual men. In 2015, and then again this year, these policies were updated. Can you explain the latest update and where that stands?

Bruce Sachais: Sure, thanks, Brian. In the past, these bans or restrictions were based on time. Men who had sex with men because of the higher rates of HIV specifically in those populations were first completely banned from donating blood. Then data came out that if we looked and for the last sexual encounter and it became a smaller and smaller interval, we were allowed to take those donations.

This is what we're talking about. What just happened a few months ago is really a major switch. Because there've been studies including something called the advanced study that has really looked at behavior independent of how someone identifies themselves by gender or sex and their sexual preferences. What we're able to do now is not ask about whether or not somebody is gay or bisexual or specifically what their lifestyle is, but we're able to look just at risk behavior.

There are some new questions that focus on that, that we'll ask everybody. In fact, we've started that last month and everyone gets those same questions. Depending on how you answer those questions, that sets you at a risk category. If you're at a higher risk, then we have to defer you for a period of time. If you're not, no matter what your lifestyle is, we're able to take you as a blood donor.

Brian Lehrer: Donated blood is tested for disease, I gather. Why prescreen at all?

Bruce Sachais: That's really an excellent question and it's hard for people to understand this but the bottom line is [unintelligible 00:10:02] test is perfect. Even when you go to your doctor, your doctor is making a decision on what tests to do because he wants the probability of a certain result before he or she sends you for that test because you can have false positives and you can have false negatives. If you prescreen people, in this case, patients, or let's say COVID. If you do COVID testing on people who you think clinically might have COVID, you're going to have much more reliable results than if you test everybody. It's a difference that you made.

The same thing is here for donors. If we can pre-screen away people who are likely to have disease, in this case, let's say HIV, then our screening test to keep HIV out of the blood supply is much more effective. We want to, again, pre-screen with questions and people's education so they understand what puts them at risk, and then people who are at lower risk, but not at zero risk, those are the people we want at that.

Brian Lehrer: Do you pay ever people who give blood? I think we've all heard stories, whether in the context of fiction or real life of people who are so desperate for the money that they donate blood and get paid for it. Is that real?

Bruce Sachais: Excellent. In the blood industry that we have, we do not pay people for blood. There are collections, there's other parallel industries where donors are paid, but for all the people that come into the New York Blood Center and donate whole blood or donate blood products like platelets or plasma for us, there's no payment. There are sometimes little perks we give out a $5 gift certificate or a T-shirt or sometimes a chance to win something in a lottery, but there's no formal payment system for that.

Brian Lehrer: What should people expect upon arriving at a blood drive? How does it work?

Bruce Sachais: When you first arrive, you'll get greeted and whether you have an appointment or not, they'll set you in a slot. You'll get questions asked of you. Oftentimes, this is on a tablet, so you'll go through and answer questions. Some of them are personal about your personal habits and some of your sexual activities and drug use. Again, that's to make sure that we're collecting products that are going to be safe for our patients. There are also questions about your medical history, and those are meant to make sure that you're safe. As chief medical officer in charge of all of our blood centers, those are my two concerns, that you as a donor are safe and that the blood you provide is going to be safe for the person who's going to receive it. After you answer-- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead, sorry.

Bruce Sachais: Go ahead.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead. No, you go ahead.

Bruce Sachais: No, I was going to say, after you do those questions hopefully if you haven't had a snack or something to drink, we'll offer that to you because we want people to have a little bit of food and, and fluid on board to make their experience better. You'll go in and have a little mini-physical. We'll check your hemoglobin which is your blood count, and your blood pressure, heart rate, things like that, and go over any questions from the questionnaire that were uncertain [unintelligible 00:13:20] depending on how you answered them.

Then you'll be taken back into an area where you'll sit in a chair and they'll draw the blood through a single needle, typically for whole blood. Although we do have other options as well. Typically, that process takes about 15-20 minutes. There's a process by which we'll talk to you, make sure you're you. We'll use some solutions to make sure that your arm is clean before we draw the blood and then the needle is inserted and the blood goes into a bag.

At the end when collected the blood, the needle comes out and we send you off after we put a bandage on, and we'll send you off to the snack bar where you can have additional snacks and fluids. We ask you to stay for a minimum of 15 minutes. Our day to say that if you're going to have a reaction, it's typically in the first 15 minutes.

Brian Lehrer: Last question. Are there any age limits? Meaning upper age limits. Can people give blood if your screening determines that they're healthy enough at any age?

Bruce Sachais: So in New York State, there is an upper age limit of 76, but if you are feeling well and healthy and come into our center, we're allowed to evaluate you at that point, or if you come at that age of 76 or later, I would suggest that you bring a note from your doctor stating that you're healthy enough for blood donation. That speeds things along a bit. If you're 80 or 85 and you're in good health and our physicians feel that you're in good health, you may continue to donate. Other states don't have that restriction on the upper end, but New York does have that bullet.

Brian Lehrer: On the lower end, teenagers?

Bruce Sachais: On the lower end, it's typically 16 or 17. New York State, you can donate at 16 with parental permission and with donor ascend. Both will fill out forms and at 17 you're able to donate just on your own consent.

Brian Lehrer: Dr. Bruce Sachais, Chief Medical Officer for the New York Blood Center. Dr. Sachais, thank you very, very much for your time and for your work.

Bruce Sachais: It's my pleasure, Brian. Thanks for having me on. Again, thanks for hosting the drive.

Brian Lehrer: Right. Again, the premise of this segment, for those of you who haven't heard it, is that we're drawing attention to something really admirable that my colleague Alison Stewart and her team at All Of It are doing. Their show is celebrating its fifth anniversary now. Rather than just have a party and pat themselves on the back, Alison and Company are staging a blood drive right on the premises at WNYC. It's this Monday and most of the slots are filled. You can try to sign up at wnyc.org/give blood, wnyc.org/giveblood. If you can't participate at our studios, you can give blood anytime in multiple locations around the city, of course.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.