The Many Creators of American English

( Jeff Robbins / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Let's talk now about identity, vernacular, and a distinctly American English language for all. With us now is Ilan Stavans, publisher of Restless Books and the editor of a brand new anthology that hits all these posts in really fun and incisive 500-year romp through the development of the way we speak English in this country today. It's called The People's Tongue: Americans and the English Language, and attracts some of the important transformations of our imperial tongue.

So many have left their mark on the language who get talked about in this book. Some of those figures are, just to name a few, Sojourner Truth, Bob Dylan, Thomas Jefferson, David Foster Wallace, Tony Morrison, and the list goes on. How about Abbot and Costello or the song Rapper's Delight, which are both in here too? Ilan Stavans, welcome to WNYC. Thank you so much for joining us on this book.

Ilan Stavans: Hey, it's such a pleasure to be talking to you and to be talking to you in English.

Brian Lehrer: What did you set out to do in this book?

Ilan Stavans: I am an immigrant from Mexico, Brian. After 30 years in this country or a little bit more, I wanted to create a love letter to the language that received me. It's an astonishingly elastic magisterial tongue that incorporates voices from all backgrounds that is unafraid. I wanted to present it in all its contradictions from the very beginning before the War of Independence, how did we speak the English language when we were settlers arriving to the Massachusetts Bay Colony, how different is that from our contemporary slangs up until Donald Trump tweeting about CNN obsessively, erratically, using the English language to pigeonhole, to bully.

The English language is the tool we have to come together. It's also the tool that we use to rip ourselves apart. We've done it for 500 years. It is time, I think, to celebrate, to look at all the possibilities that it allows us.

Brian Lehrer: I will skip over the first two entries in the book, which are about Anne Winthrop in 1581 and Robert Smith in 1687, to your third and fourth entries, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. How did the founding fathers think or write about American English that you wanted to highlight?

Ilan Stavans: Imagine creating a new country, Brian, what do you need? You need a territory. You need a vision of a common history. You need eventually a post office, a central bank, a flag, a national anthem, and that's when you start realizing that you need a coalescing form of communication. The founding fathers understood this very well. Although they decided not to make English the official language, they left it to us to battle the language, to shape it, to polish it. In these two major figures, many of the founding fathers were very attuned to the nuances of the language.

On the one hand, John Adams had a vision that if we don't protect the language, it will go, as he said it, to the dogs. He proposed, fortunately never realized this dream that he had, that we create the equivalent of the Académie Française, a federally funded institution that would protect the language and allow it to contain its development. On the other hand, Thomas Jefferson, a polymath, a renaissance man, fascinated with grammar and syntax who knew different languages understood that the best thing you can do with the language is just let the people play with it.

There you have it, the two essential figures at the very beginning of the republic wondering what's the authority that keeps our language intact, that will protect it, and to what extent we should just allow the people to do with it as they wish. It is, after all, a language for the people and by the people. That tension between the two, Adams and Jefferson, plays out until the very present. There are those who say that immigrants are coming and are destroying our language. They are not learning fast enough, that they are bringing words from Spanish and Haitian and African languages and Asian languages and as a result, the poor English language is deteriorating, is dying baloney. On the other hand--

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead. On the other hand. I thought you were going to land on bologna, which we certainly could, but what's the other hand? [chuckles]

Ilan Stavans: Baloney is a perfect word to state this. On the other hand, the baloney is exactly what we have. All these words that the immigrants bring in, a nation of immigrants is a nation with a language that is ever expanding and being renewed. Just think of all the words that Jews and Irish and Italians and the Germans and Caribbeans have brought into the language to the point that if we were to sit together with Adams and Jefferson at a dinner table, I think they would only understand about a third of the parlance that we use.

Brian Lehrer: Only a third. I even think of this as an analogy to the debate that we always have in this country today and at the Supreme Court about how to look at the constitution that those same founders drew up. Is it a living document that we take inspiration from to adjust the principle of to the time, or do we look as the originalists do, just at the text that the people in John Adams and Thomas Jefferson's generation would have written? Your next entry after John Adams and Thomas Jefferson is Noah Webster, the dictionary guy. Webster pegged to the year 1828. How about Noah Webster?

Ilan Stavans: A beautiful moment in the history of this country. The Webster is a figure that remains a eclipsed founding father. He had this project that if we wanted to become a full-fledged autonomous and proud nation, we needed our own dictionary. He created the very first one. Part of it he plagiarized from a Dr. Johnson's official or authoritative dictionary of the English language published in England, but he incorporated a lot of words that they were already circulating in this country. 1828, he included about 70,000 words in this first dictionary, The American Dictionary of the English Language.

Eventually, the Webster dictionary became the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a commercial endeavor which in the US is very important because the British have the OED, the Oxford English Dictionary, which is not a commercial endeavor, it is by Oxford University Press. One is a non-profit and one is driven by money. Just in 1993, there were already 700,000 words out of the 70 that the Webster had included. Imagine how much our vocabulary is expanding by the day. We have many, many more words now than the founding fathers or the settlers had.

One of the fascinating questions is where the words come from, who creates them? How do they become accepted? Do other words die? Do we have a limited number of words to use and are those words in constant circulation? Are the young more prone to create new languages and older people more given to protect and be conservative about the language? All those are essential aspects to understand the type of vocabulary that we use every day.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, who wants in on this? Whose contributions to American English would you like to shout out? We're talking about figures hundreds of years old so far. We're going to go chronologically gradually toward the present. We're going to get to Rapper's Delight by The Sugarhill Gang. We're going to get to Abbott and Costello, believe it or not. There are so many other contemporary people who you might list for the contributions to American English, or if you're into it in this way, some people from any point in American history. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet your word contributions.

Who were those contributors really of words or ways we use English? Tweet @BrianLehrer for Ilan Stavans who is the author now of The People's Tongue: Americans and the English Language. Just going down this table of contents, which is really a list of dozens of names chronologically over time. We just talked about John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Noah Webster in the 1700s and 1800s. Then Alexis de Tocqueville comes a little after that, and pegged to 1851, Sojourner Truth. I imagine you could talk about any number of anti-slavery figures, Sojourner Truth's Ain't I a Woman? speech might be her most famous thing and it might not have contained that phrase. Why Sojourner Truth and why 1851?

Ilan Stavans: Because this is a moment in which would eventually become a major figure in the anti-slavery movement, uses the English language in her own way. The aim is a statement of what can do with contractions in this country and what African Americans adopt and reinvent as they shape the language. I think with her and connected with her, the Gettysburg Address that Lincoln will deliver, barely 400 words that are some of the most extraordinary, some of the most sublime in American English give a statement that the language is not only for those who have power but those who have been controlled. They subvert the language in strategic ways that leave waves into the future.

From Sojourner Truth to James Baldwin to Toni Morrison, we have Black English that is crucial to understand what has happened to this country as a result of slavery and as a result of oppression. I think this is a crucial part among other things, Brian, because the language that we speak is also the lang that silences, that we bury in it. For every word that we have, we also have the Native American words that were suppressed, that were censored. They're silences that became much more loud than words themselves in the process.

I think of language as a laboratory of exploration. I also think of it as a cemetery of the voices that were left behind in the process. I think it is important to champion those like Sojourner Truth that made a statement that continues to reverberate in the way we see women and in the way we see human beings today.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, am I right that English was Sojourner Truth's second language, she spoke Dutch first?

Ilan Stavans: Yes, absolutely. Beautiful in fact, which is also a statement of how in this country, multilingualism is a feature that defines who we are. Although there are constant movements to eradicate other languages and make English the sole official supreme one, the fact is that the negotiations between different languages within the country and at the global level kept keep on nurturing how we speak. We have many words that come from the French and from the German and from the Italian, and we have donated many of our words to the French, to the German, and to the Italian. That is the give and take of languages that are alive.

Brian Lehrer: You mentioned Native American contributions to American English. I think Beth in the Bronx wants to continue on that. Hi, Beth, you're on WNYC.

Beth: How are you? I think if I remember from Albert Marquardt's book that the word hurricane is a Taino Native American word from hurakáno or hurakána. I believe that they were one of the original tribes in South Florida and in the Keys. Am I right? Am I wrong? It's a long way back since I took this course.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] Do you happen to know that detail, Ilan?

Ilan Stavans: You are absolutely right. Hurricane is indeed an Indigenous word, and there are many other words that come from Indigenous languages that are a fixture of the English language. Just start by naming the states of the Union. More than half of the states have names that come from Indigenous languages. That is how those lands were first described. That is how we continue to describe them. Even though we struggle with recognizing the heritage of those names and those languages, they are there to remind us of the past geographically and linguistically.

Brian Lehrer: David in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, David. David, are you there?

David: Oh, hello.

Brian Lehrer: Hi there.

David: Yes, I am. I am very, very far from a teenager, but I remember as a kid, I was a teenager in late '50s, early '60s, adapting words and that were tried to be stifled by older people. Like when you watch the early rock and roll movies are like, "Oh, that's boss. It's far out, groovy." By the way, I'm still trying to keep groovy in the language, but to not much avail.

Brian Lehrer: It was once this new teenage word. Now it's, "Oh, haha, groovy, that was such a long time ago." David, thank you very much. How about his concept? Does it appear in your book that teenagers often change American English?

Ilan Stavans: Teenagers, young people, Brian, are the ones that dare. They are rebellious and that rebellion is showcased in the way they rename things. They bring new words into the vocabulary, but they also reformulate them. I remember arriving to this country when Michael Jackson was a major popular figure and the word bad was transitioning, let's use that term, from meaning something negative to meaning something positive.

A word that we accept, like the word they or the word he, the word bad has now a different connotation, the same thing with the word gay. Shakespeare, were he to come here, he would not understand what we mean by gay because, for him, gay meant happy. It's not only that the young bring new words, is that the young, in particular, refashion words, make them new, give them new definition.

Brian Lehrer: Your chapter on slang in America is pegged to Walt Whitman in 1885. How come Whitman and slang in America?

Ilan Stavans: Because Whitman was a voraciously ambitious poet who loved not only ethnic diversity but linguistic plurality. Every sound in his ear seemed to be resonating in different ways and pointing to different directions. The beauty of Leaves of Grass and the beauty of how he plays with the language is that he wants to make room within that language to the slangs that he hears of the Blacks and of people from Cuba that live in New York at that time.

That is his biggest contribution in my view, that he is receptive to the languages of the working class that are on the streets in restaurants as nurses during the Civil War in that he inserts them in his poems and in his writing. He has that beautiful thing that is included on the book how slang is really pushing the language to the future instead of how certain more conservative figures think that it is dragging it down and polluting it.

Brian Lehrer: Ilan Stavans with us, if you're just joining us, and his wonderful book, The People's Tongue: Americans and the English Language. This is told in many short chapters pegged to many individuals or, as we will hear, sometimes teams of individuals through time. Now we come up more toward the present into the era where there is tape to pull from things that people have said. Page 168, Bud Abbott and Lou Costello, Who's On First, 1944.

Bud Abbott: I'm telling you, Who's on first, What's on second, I Don't Know is on third.

Lou Costello: You know the fellows' names?

Bud Abbott: Yes.

Lou Costello: Then who's playing first?

Bud Abbott: Yes.

Lou Costello: I mean the fellow's name on first base.

Bud Abbott: Who.

Lou Costello: The fellow playing first base for St. Louis.

Bud Abbott: Who.

Lou Costello: The guy on first base.

Bud Abbott: Who is on first.

Lou Costello: What are you askin' me for?

Bud Abbott: I'm not asking you, I'm telling you, Who is on first.

Lou Costello: I'm asking you who's on first?

Bud Abbott: That's the man's name.

Lou Costello: That's who's name?

Bud Abbott: Yes.

Lou Costello: Go ahead and tell me.

Bud Abbott: Who.

Lou Costello: The guy on first.

Bud Abbott: Who.

Lou Costello: The first baseman.

Bud Abbott: Who is on first.

Lou Costello: Have you got a first baseman on first?

Bud Abbott: Certainly.

Lou Costello: Then who's playing first?

Bud Abbott: Absolutely.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] The name of the first baseman was who?

Ilan Stavans: [chuckles]

Brian Lehrer: That of course is a classic very funny bit that can make me laugh even after hearing it about a zillion times, but why did you include it in the book on the development of American English?

Ilan Stavans: I just love-- Like you do, Brian, I love that segment. It is something that Dr. Seuss will go do later turning a word like who and who they are into a name and then doing so playfully so that children can enter the language and see how plastic it can be. The tension between Abbott and Costello and the fact that one wants to know the name and the other one is naming the person by simply stating the position on the field that they are in really showcases the way comedians in standup make the language, have new ways of sounding and new ways of feeling.

People laugh at it, but then it leaves a mark. Those of us who speak it will go back to it and see that there's poetry. I think there's enormous and gorgeous poetry in Abbott and Costello. It's not only the poets that make poetry, it is the musicians and the standup comedians, and sometimes the activists who can turn the language not only by saying what they say but by doing so eloquently and intentively.

Brian Lehrer: Sometimes, for better or worse, it's the corporations, as I think Laura in Manhattan is going to cite. Laura, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Laura: Good morning. I am loving this topic. This is one of my favorite topics. Thanks for this and I'm planning to get the book. I'm a trademark attorney, so I spend a lot of time thinking about words and names. There are a lot of names that were originally brands that fall into common parlance and become generic, and then they're a part of the English language. Examples include escalator, aspirin, trampoline, cellophane, all those were originally brands for their products. The companies fight to try to keep them from becoming generic. Google and Kleenex are a couple of examples of that now, rollerblade. For some, it was just too late and now we ride the escalator, not the moving staircase. You take aspirin, it's the pain reliever.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Wow. So many examples, Laura. Thank you. Do you get to that at all in your book, corporations, either by design or just by the virtue of success that their products become named generically?

Ilan Stavans: Yes. I love what Laura was saying. It's easy to demonize and practical to demonize corporations, but corporations are also machines of word production. Many of these words end up replacing something that could be easier to describe. Think of the word Xerox, the word Q-tip, or the word Cheerio. We can say cereal, we can say photocopy, but people just by default go to these words and the words can become nouns, can become adjectives, can become adverts.

These words are essential to how we communicate every day. They are snippets of information that we can all recognize. It is crucial to recognize that advertising business, corporate endeavors are major contributors to the parlance of every day. That is what American English is also in. Either we want it or not, there's poetry in it. We might not like what they do, but there's beauty in those words, and beauty in how those words can be pronounced in different ways in different parts of the country with different accents.

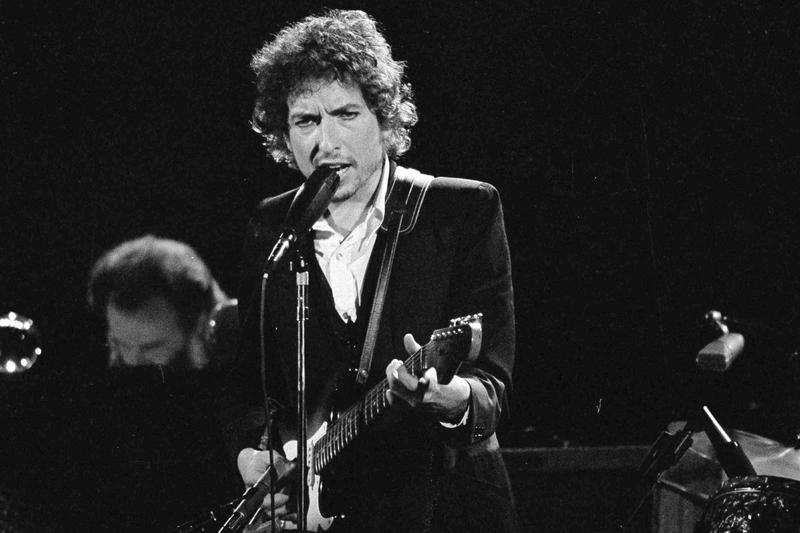

Brian Lehrer: As we continue to move toward the present and as we start to run out of time, Bob Dylan was the first musician to win the Nobel Prize in literature. You include his 1963 song, A Hard Rains Are Going to Fall. Some other folks as we move toward the present, Richard Pryor, Paul Mooney, Tony Kushner, the playwright, Toni Morrison, the late novelist, Kendrick Lamar who won the Pulitzer for rap album DAMN.

So many contemporary poets and writers, Joy Harjo, Natalie Diaz, but 1979, The Sugarhill gang, remember? Here in this year that we're celebrating as the 50th anniversary of the origin of rap in 1973, that was 1979 and that was really the first rap song that a lot of people heard as it became a big hit on general AM radio. Why do you include it in the anthology on the development of American English?

Ilan Stavans: Brian, let me bow down and thank rappers for their contribution to American English. The spontaneity, the inventiveness, it starts 50 years ago and we would not be who we are. I think they have freed us from the restrictions that the previous generations had established or had continued. There is astonishing creativity in what a rapper can do. It is thanks to the hip-hop generation that we have become much more of a fusion language, and we have pushed words beyond their own borders. I wanted to include that beginning, but if I could, I would have included many, many more rappers and hip-hop artists. I think they have the beats. They tell you where the language is at any given moment.

Brian Lehrer: We leave it there with Ilan Stavan. Stavan is S-T-A-V-A-N-S. If you want to look for the book, it's called The People's Tongue: Americans and the English Language. This was so fun, so wonderful. Our board is lighting up with callers. We could continue this, but I recommend everybody to the book and you can see all the other contributors to the development of contemporary English in this country that we didn't get to. Thanks so much for coming on with us.

Ilan Stavans: Such a pleasure. It has been a joy. Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.