Making Remote Instruction Better for All Students

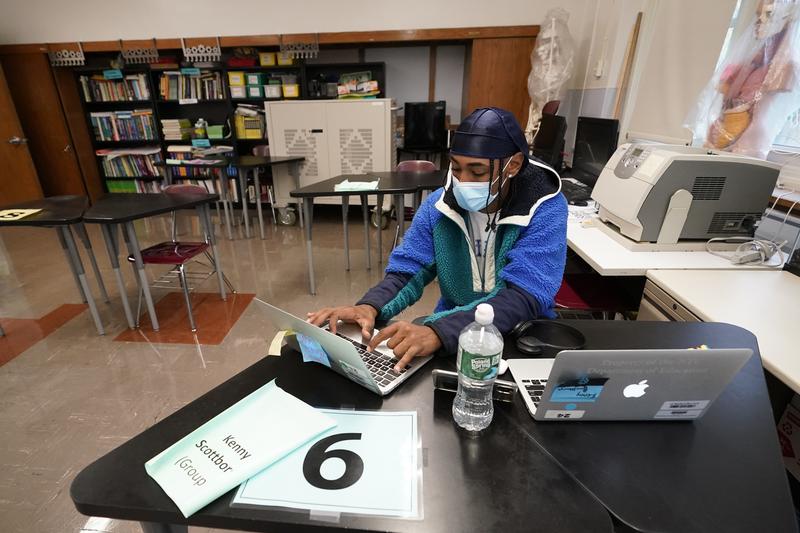

( Kathy Willens / AP Images )

[music]

Brigid Bergin: It's the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Good morning again everyone. I'm Brigid Bergin WNYC's City Hall and politics reporter, filling in for Brian today. If you're familiar with the Brian Lehrer Show's weekly Ask the Mayor segment. You'll know that remote learning is a frequent topic and has become something of a tagline for the show. For teachers, parents, students, and especially students with the greatest need, it's been tricky to navigate. School in a pandemic is challenging to say the least, but experts say there are ways to improve remote learning.

With me now to talk about some of them is Christopher Emdin, Associate Professor of Science Education at Columbia University Teachers College. Listeners, we want to hear from you too. What are your remote learning questions for Professor Emdin. We'd like to invite calls from anyone looking for ways they can make remote learning work or work better. Give us a call at 646-435-7280, that's 646-435-7280 or tweet us your question or comment @brianlehrer.

Christoper Emdin: Can you hear me?

Brigid: Welcome to WNYC.

Christopher: I'm glad to be here with you.

Brigid: Great. Now, Professor even before being forced into the position to learn how to do school virtually, teachers have always had to be creative. Now, many are having to come up with their own best practices. Starting off on a good note, what remote learning successes have you seen in the last eight months?

Christopher: The first thing is that young folks who don't do well with the traditional school schedule, have been able to have a lot more agency. When they want to engage, or when they can engage are working on assignment at times that are not during the school day. I've had opportunity or seen opportunities for parents to be able to chime in on the conversations, in ways that they couldn't do before.

Teachers are finding new and innovative ways to be able to forge connections with communities. A bevy of things are working well. It's essential for us to recognize that even though we've had some challenges with remote learning. For a lot of young people that traditional school does not work well for, they're having their best learning experience.

Brigid: At one point this fall Professor, New York City public schools were still lacking something like 77,000 learning devices like tablets and laptops. How can parents create learning environments for students, specifically, in circumstances where they may lack the space or internet connectivity, or even these devices?

Christopher: The concept of remote learning is so interesting. We think about it as the interface with the teacher, but learning in itself is such an iterative and organic process. If there's a place at home, that you create, that is about learning, it's about reading. No matter where you live, a small corner with a comfortable seat that is dedicated to the learning enterprise, or the exercise works really well. I always say we do not give the responsibility for learning to the school or the teacher, they are our supports in that endeavor.

Creating a learning environment at home that's comfortable, and a pattern for young folks to feel as though I'm going to my learning space for a certain amount of time a day. Helps them when they're able to go online and remote, when they do get those devices that they return to that same setting. Another thing I always suggest is that we think that online learning requires the latest software and latest devices, and it's oftentimes really expensive.

When you on a local store at AT&T store, a T-Mobile store, and buy a device from three generations ago. As long as you have internet access, the older device works just well for a Zoom or Google Meet. That innovation and the use of technology and creating the space at home, that is the learning space. Really helps when there's instability with the larger school structure, that there's always stability around a learning environment at home.

Brigid: I have to comment that one of our producers Carl Boisrond made the very appropriate comment that our experience right now really highlights some of the challenges posed by remote learning. This technical ability to connect, it's something that certainly we're experiencing here in live radio. But also can be a challenge for students and parents and teachers as they try to do the very important work of conducting the daily lessons. One of the things I've heard from some parents and advocates, is that we may be losing a whole generation of children because remote learning isn't working because of the inequities it's exposed. What do you make of that sentiment?

Christopher: I come from the camp that says, "We will never lose a generation of young people." They will find ways to be able to connect, when they can connect with each other and with educators, they will speed past the time that we've lost. We have to operate with some optimism about the infinite potential of young folks to find their way. I also think about the idea of connection, not requiring technology.

There were ways that we use to communicate and times past that are just as effective and we threw them out in pursuit of technology. We thought that the more complex the devices, the better we would be. I've seen such magical dialogue between teachers and students or students with each other in regular mail. The anticipation and waiting for my friend to be able to finish the note. The waiting for the mail to show up.

The conversations about patience and resilience and thoughtfulness and reflectiveness. Preparation for when I write my letter to my friend what is going to be, and I'm working towards until I get the letter. I think what we need right now is an a recognition that technology is beautiful and magical in many ways, but it will fail us, like during this call, right? I went through a prep with you guys, and this fell to pieces. However, I can still engage with you, right?

Brigid: Absolutely.

Christopher: We can set up a part two. I can write you a note about my thoughts. I want us to not rely solely on technology, we utilize it as a support when we have it. There are age old practices for connection, emotional connection that are just as valuable and that help us develop skill sets that may be lost in technology. Young folks now exist in a culture of immediacy, they expect everything right away. The such beautiful intellectual and pedagogical lessons are the slow moment and the reflective process. I always say to teachers, and to parents, emphasize what you can learn in this moment, and when we're back in person, we can fix the rest of it.

Brigid: Let's take a caller. Jonathan, in Queens, you're on the Brian Lehrer show with Professor Emdin, what's your question?

Jonathan: Hi, thanks for taking the call. It's not a question, it's mostly a comment on what you guys are just experiencing on this call. I work in a school where many of the families do not have WiFi and the issue is always connectivity. I work in an area where they received a lot of the DOE ITABS and it's getting better, but the biggest issue with remote learning is connectivity. Making that something that the city thinks about moving beyond the pandemic, to equalize the playing field.

Because you just talked about how you just had a problem connecting and eventually it worked, but that's because probably you're coming from places where you have good broadband and a good WiFi. For the kids, especially the younger kids, the elementary kids, the problem with connectivity creates a lag that really disrupts the whole educational process. Touting the remote learning and making it as best as you can now is great, at the same time the main issue is connectivity.

Brigid: Jonathan, did you say you're a teacher in Queens?

Jonathan: Yes.

Brigid: What and grade do you teach?

Jonathan: Elementary school. I'm a music teacher but I actually have become the tech point person at the schools during this time, because [crosstalk].

Christopher: We could have used you earlier Jonathan, for us [laughs].

Jonathan: I heard it's happening, and I said the same thing like this is the issue.

Christopher: It is.

Jonathan: I hope--

Christopher: I wholeheartedly agree, Jonathan.

Brigid: Go ahead, Professor Emdin.

Jonathan: [unintelligible 00:08:52] I'm sorry.

Christopher: I wholeheartedly agree. Touting remote learning as a be all and end all, nor am I saying that we should rely on that alone. In fact, I'm saying a bit of the opposite, that we use it where we can, but should not fully rely on it. Even with issues with connectivity, one powerful practice I've seen is a really great asynchronous instruction that is remote, but allows for the lag and connectivity to be overcome. For example, a teacher who wakes up at three o'clock in the morning with inspiration and that's the beauty of good educators, right?

3:00 AM something strikes you, "Oh my gosh, I want to share this with my kids so badly." You can literally get on your device, record that lesson or that lecture, send it via mail. While there may be some lag in stuff like the synchronous access, we can be really more creative with our asynchronous learning. Again, not ideal. The ideal scenario is that we are with our babies. With a bit of creativity and innovation and a bit of reliance on substance like ingenuity and past practices, we can overcome some of those challenges.

Brigid: Professor Emdin, you hit on an issue that I think is really important for a lot of teachers and students and parents. That's that emotional connection that students can get by being in a classroom with their teacher. When you're only seeing your teacher from a computer screen, whether it is live or something that they've taped ahead of time, you're not necessarily getting that connection. How can teachers just be there for their students, even if the under classroom isn't possible?

Christopher: The asynchronous learning is not in-person, but that's one way to do it. I'm going to go back to my suggestion from earlier with snail mail and pictures that goes a long way in forging a connection. I love the concept of pen pals, but also importantly, teachers are invaluable. We cannot say enough how important it is for young folks to force connections with their teachers. It's also a season for us to be able to find other adults in our lives that young folks don't have access to and help them to forge those relationships as well.

I've seen instances where parents have written a letter to a college professor that does something in science and conducting research. Said, "Will you be willing to call in or Skype in because my [unintelligible 00:11:25] is Looking at your research?" It's a really interesting thing that we have to consider here. We have scholars, thinkers, professionals, engineers, architects, et cetera, who are dying to make a connection and have an impact in the world beyond their craft.

Then we have young people in communities who so need access to folks who inspire them, folks who look like them and see careers. They we're not getting this pre-pandemic and they certainly aren't getting it now. What we can do now is start forging those inter-generational connections, so that young people can have a bevy of caring adults in their network that can supplement what's missing when the young person can't be with the teacher.

Brigid: If you're just joining us, you're listening to the Brian Lehrer show. I'm Brigid Bergin, a reporter and the WNYC and Gothamist newsroom. I'm joined by Christopher Emdin, Associate Professor of Science Education at Columbia university Teacher's College. We're going to go back to the phones. Let's talk to Chris in Manhattan. Chris, welcome to WNYC.

Chris: Oh my gosh, I am flush to be able to join you guys, how are you today?

Brigid: We're great. Tell us about your experience with remote learning.

Chris: Okay. I'm just trying to navigate one technology. One of the more important things is that the DOE has said that leave your kids alone, let navigate their own machines, stay out of the room. They either have to open or close or figure out things and all the rest, but the more a parent gets involved, the more you're enabling your child to not learn. It's like getting really weird. That's the one thing. The second thing is, I can't believe that they're opening the schools again on the seventh, even after we've been warned that post-Thanksgiving pre-Christmas is going to be the one of the worst infection periods ever.

My third point is I don't even know, my questions and concerns are there and I don't know, whether or not you can get that technical logical connection. The kids have so many different touch points that they can figure it out and they're so much smarter than we think they are. I don't know. I appreciate this topic and I don't know. I hate to sound like I'm venting, but I'm concerned, I'm worried. It's just like weird because I got a five-year-old and she's awesome and I just want to make sure she grows up awesome. That's it. I'll take my [crosstalk]

Christopher: I don't think it's venting at all. I think these are legitimate concerns. I think as an educator and an advocate for educators, I think that our collective culture that makes teachers disposable is so problematic. When we're talking about remote learning, our anchor is always how the student is feeling, well, we must also focus on how teachers are feeling and their challenges with technology, et cetera. One suggestion I would give is also sometimes the Zooms and the Google Meets are not the be-all and end-all.

Young folks are brilliant and genius at technology. I've seen Instagram classrooms that have been absolutely amazing. One of my students has a class solely dedicated to her biology students, where she has images and dialogue that's going on beneath the images on Instagram. There's Twitter groups that are guided by an adult or by young people. Any experience that you have where young folks are connecting with each other can be a platform that we can use for learning.

TikTok is an amazing tool for learning that young folks are using right now. I think there is a curve, adults are not really keen in the social media platforms that young folks are engaging in and with. We can learn with students or most importantly, what young folks love the most is saying, "Hey, look, we're on Zoom today, I'm asked to be on Zoom. I know you guys are all on Instagram, you're not getting on Club House. Why don't I teach you a little bit of math and English? And then we'll have another session where you're teaching me how to use social media."

This is a way that gets young folks to engage in a way that's not passive. Usually it's a teacher teaching them and they love teaching us about their platforms. Then there's this exchange where you teach them content, they teach you how to communicate on these tools and that mutualism fosters a respect for the learning enterprise that even traditional schools does not offer.

Brigid: Let's take another caller. Raymond in the Bronx, Raymond, welcome to the Brian Lehrer show.

Raymond: You know what? I am so excited to hear the professor speak. That 3:00 AM inspiration is something that I said to my wife, because a five-year-old and a four-year-old in New York City schools. I said, "I wish they would have a syllabus style thing where they can go ahead and do the works and separate from the screen a little bit. Maybe go downtown to a park and take the lesson there and then if they have any question, to make a Zoom appointment with the teacher to get the nuances of the lesson." Just to separate from the screen a little bit.

Then also I work in telecommunications and I think they may had missed a great opportunity during the summertime too. Because all the school buildings are different at ages. That would've been a prime time, whether we had found a cure for the pandemic or not to just future-proof the schools. I'll leave it to you, Professor and let you know.

Brigid: Raymond, thanks so much for calling.

Christopher: Thanks for that comment, Raymond. I have to say this, I know we're talking about education, but the most insightful and brilliant comments from anyone in the world always come from the Bronx [laughs]. As a Bronx guy I got say that.

Brigid: You had to get your shout out in.

Christopher: I agree with your points, Raymond. I got to throw the Bronx out in there. Here's the thing too. One of the most groundbreaking movements in education over the last two decades has been the flipped classroom. The underpinning argument of the flipped classroom is that the things that young folks would traditionally do when they were in the classroom, they'll do out in the world. I think that this is a ripe opportunity for the flipped classroom.

Just to extend on Raymond's idea, this is the time for young folks to do scavenger hunts of their neighborhoods and environments. For teachers to create lessons based on that. It's also the time for the teacher on their own to identify the neighborhoods that kids may come from. Just take a quiet walk, take some images from their local settings and then design lessons based on that, that you can mail to them.

They love the idea that their teacher has been where they've been, that their neighborhood is featured in the assignment. These are things that don't require you to be with the young folks all the time. But rather create this cultural toolkit of images from their neighborhoods that you can lessons around. I think that that's something that'd be great for teachers to do in a season.

Brigid: Professor Emdin, I just want you to clarify a term I think you just use, you said flip classroom, is that right?

Christopher: Yes, I said flipped classroom. The concept then was that a person could record or teacher could record the nuances of how to describe a lesson or balance an equation or do some algebra. Would record that and then young folks would use their time and watch that. The kids would then watch that on their own. Then they can use their time in the classroom to pose questions rather than have the classroom time be the place where the teacher was delivering the main instruction. Teachers can flip classrooms now, record the video, share with young folks. Then whenever you guys can meet, you can work through the details, but just so they can have access to you and see you on video.

They can slow down the video if they need to, they could watch it a million times beforehand. There's some beauty and asynchronous learning that synchronous learning cannot capture. Because asynchronous learning allows the young folks to create their own pace, allows them to have their own space, and allow them to have time for reflection. When we look at remote and think about remote, we get so tethered to, on time live instruction that we don't give enough attention to that asynchronous reflective process.

Brigid: Professor, as with so many issues right now, education is an area where existing disparities have been uncovered even more so by this pandemic. I'm wondering how much more challenging has remote learning been for poor kids and Black and Brown students and students from any demographic that has really been disparately affected by the ongoing pandemic?

Christopher: Look, we have a structure and a culture in contemporary education that is built on the backs of Black and Brown young folks, and they always suffer the most. It's just a reality. You're right, we've seen that much more now than ever before. However, every time that folks talk about the immense suffering, that Black and Brown folks and socioeconomically deprived folks undergo. I want us to at the same time have a conversation about the innate resilience, the innate creativity, the forms of expression, that are coming out of those same communities.

I think that when we keep making teaching be based on what young folks are losing, we don't trigger the imagination, to create instruction based on what they're doing. Right now, there's a young person who could not do well in traditional school who's at home, downloaded software to their iPad, and is creating beats, and is creating all 16 bars and 4 bar hooks, and they're doing mathematics right now at home. They will always suffer, if we're looking at mathematics through the lens of they're not sitting in front of us, and we don't have a textbook.

What we need to learn is how they're being creative, and expressing their innate mathematical and scientific identities in the moment, and learn how to be nimble. We will always be unsuccessful, if the expectations and the structures that we are using is based on a model for teaching or learning that we know pre-pandemic and during pandemic will not serve this population. What we have now is an opportunity to be creative, to be nimble, to be inventive and to center young folks. Let them teach us about the way forward rather than utilize our old tools to assess them and see the underperforming or say that they're not meeting benchmarks. They're surpassing benchmarks, we're just using the wrong assessments.

Brigid: When you describe re-imagining how some of this teaching is done. I'm wondering, what aspects of remote learning do you think are here to stay, and eventually when students and teachers are back in the classroom, will there be a new normal, on many levels?

Christopher: I firmly believe from the depths of my soul that all of it is here to stay. We certainly cannot replace, in person teaching. There's nothing like the magic of looking into a student's eyes and being able to touch their soul, by the words you speak. There's something in that physical space that it just can't be touched. I do think though, that there's nothing that is more powerful than the connections we forge from young people once they leave the classroom. We know all the loss that happens over summer, for example. We know what happens when there's a long vacation, every teacher who's listening right now knows this.

We went through all this stuff with the kids, and then there's a three day weekend and on Tuesday, they come back and they're like what is going on in the world. I think remote learning helps us do it. For those of us who have forged strong connections to young folks in classrooms, that turn them on to learning. This new world of understanding, remote learning allows us to sustain that when they're not in our physical presence. The emotional connection is generated in the classroom, but it's sustained in the work we do outside of the classroom, and sometimes through these remote tools.

Brigid Bergin: We'll have to leave it there. My guest has been Christopher Emdin, Associate Professor of Science Education at Columbia University Teachers College. He joined me to give us all a lesson in the challenges of remote learning and the ways we can forge ahead and make it better. Thank you so much for being here.

Christopher: Thank you so much for having me with you.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.