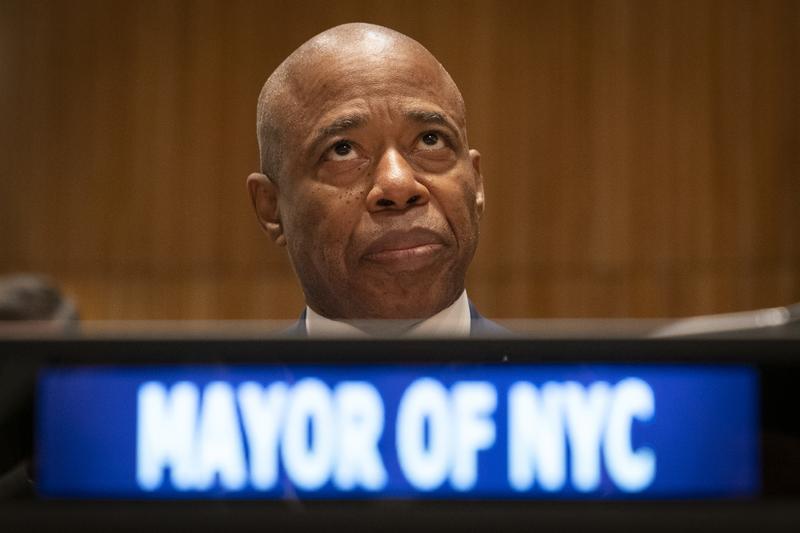

NYC Politics: Adams Clears Homeless Camps, Calls Himself 'Wartime General'

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Mayor Eric Adams is on the war path literally.

Mayor Eric Adams: Generals come during wartime and peacetime. This is a wartime. COVID is a battle. Our economy is a battle. Crime is a battle. I'm not a peacetime general. I'm a war time general and I'm not going to lead this city from the rear. I'm going to lead this city from the front.

Brian Lehrer: From the front. That was last Thursday as he announced the end of the vaccine mandate for athletes and performers working in person. He had more fighting words over the weekend, talking about his anti-crime strategies, including jail time for more people charged with crimes.

Mayor Eric Adams: This is just fixation on the bad people in the city. I have a question today. What about the good people? What about the people that don't break the law? What about the people that don't speed? What about the people that don't carry guns? Do they matter?

Brian Lehrer: Good people versus bad people. This week, yesterday, the mayor defended his hundreds of sweeps in the last few weeks of encampments where people experiencing homelessness live.

Mayor Eric Adams: As the mayor of all of us, including my homeless brothers and sisters, I'm not leaving any New Yorkers behind. We're moving together. That is the goal of what we must accomplish. I'm not abandoning anyone. I'm not believing that dignity is living in a cardboard without a shower, without a toilet, living in terrible living conditions.

Brian Lehrer: Eric Adams yesterday. Like or dislike his policies, think they're effective or not, Mayor Adams is making his mark as he completes his third month in office today.

Let's take a closer look with WNYC and Gothamist reporter covering mayor Adams, Elizabeth Kim and Juan Manuel Benitez, political reporter for Spectrum News NY1 and host of Pura Política on their Spanish language station, NY1 Noticias. Good morning, Liz and Juan Manuel, welcome back to WNYC.

Elizabeth Kim: Morning, Brian.

Juan Manuel Benitez: Morning, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: What's this good people, bad people thing? Juan Manuel, that's such an old school way of talking about people from marginalized or disadvantaged communities who wind up getting involved in crime.

Juan Manuel Benitez: I think, Brian, that I'm a little shocked that some people in New York are shocked at Eric Adams. This is what New Yorkers elected. They elected last year, a cop as mayor. This is the same speech, the same Eric Adams that we saw during the campaign. He campaigned on public safety and this is what he is doing. At least he's trying to tackle the perception of the lack of public safety. Something that is extremely important at this time, just because even though we see some certain crimes going up in the last couple of years, the thing that has skyrocketed in the city and I'm sure you agree with me, Brian, because you talk to New Yorkers every day, is the perception that the city is not as safe.

That perception has a certain way of being tackled. One of those ways might be trying to eliminate certain things like homeless encampments in the city, try to eliminate them so New Yorkers walking by them don't feel that the city is going out of control. Whether that is effective in the long term, well, that's still up in the air and as Liz has reported this week, only, I think, five people have accepted a shelter in the city of more than 200 encampments that were eliminated this week.

Brian Lehrer: A pretty shocking number and we'll talk about it with Liz and with you in some detail when we get to that part of the conversation, but Liz, to follow up on what Juan Manuel was just saying about perception, to read the tabloids and even on Juan Manuel's NY1, which is not a sensationalist news organization, it seems like every day there's another individual shocking crime that makes the news.

Stray bullet hits three-year-old outside daycare center last week. A guy smears poop on someone in a subway station, knifings or shootings or beatings, sometimes in big public places, sometimes in broad daylight like Penn station or the person left in critical condition by a mugger at the McDonald's at 34th and 7th. Just this week, Queens pizzeria owner stabbed after trying to stop a woman from being robbed outside the store is another one this week. Do you think we're seeing that much more violence or violence in previously safe spaces or some more violence, but exponentially more reporting on individual incidents driving this perception?

Elizabeth Kim: I think the latter is certainly true. I think that we need to acknowledge that human beings tend to have a bias to fixate on the worst crimes or the worst stories. I think the tabloids feed into that as well. On the other hand, if you look at the NYPD data, the data is clear. Major crimes year to date are up 45%. In part, I see Mayor Adams' rhetoric, which is getting tougher and tougher, which every week, it's corresponding to that statistic because it's 45% now. I remember just two weeks ago, I looked at it and it was in the 30s.

We're seeing this rise. We're seeing surveys come out where New Yorkers are saying they don't want to go back to work. They don't feel safe taking the subways and they won't go back to work if they don't feel safe on the subways. There is so much pressure, I think, that the mayor is feeling that he needs to get a handle on this.

Brian Lehrer: Do you both agree that it's too early in his tenure to blame Mayor Adams for the increase in crime on his watch? Today's the end of the first three months, March 31st, he was inaugurated New Year's day, but crime is going up. One might have guessed that just having the tough talking mayor was going to dissuade people because they're going to feel intimidated, they're going to feel likely to get in more trouble from the crackdown, but it's going up. Liz, what should we make of that?

Elizabeth Kim: I still think it's too early, because I think from the very start in talking to experts, crime is a notoriously difficult issue for mayors, and New York city mayors in particular, to tackle. It's like there's so many other factors. There's the economy, unemployment, then layer onto that, we have this pandemic which is a major disruption. There are many people who still feel that because crime has gone up not just in New York city but across the country, that it really is due to the pandemic. If the pandemic were to resolve itself and then we see a lot of other things come back, like regular services are put in place and jobs come back, that crime will gradually go down, but we're not there yet.

We still see that there's still a variant. There's still questions about, should we mask? Should we not mask? Should we get a second booster? I think that because of this question, it will be very difficult for him three months in and even six months in to really make a real dent in crime.

Juan Manuel Benitez: I don't think Brian is fair to blame Mayor Adams just yet. Crime, when it comes to going up or down, those are normally long term trends and we've seen that trend going up for the last two, three years in the city. Let's remember that New Yorkers got used to a very safe city. The numbers were at historic lows in 2017 and it's really hard for New Yorkers to really come to terms with the fact that maybe we got used to numbers that were extremely and not really realistically low.

Then talking about also the perception, because obviously the numbers are there and the NYPD statistics, we've seen them. We are coming out of a two year pandemic that has been extremely disruptive. Also, a lot of New Yorkers have spent almost two years holed up in their houses, in their apartments, really scared of what was happening around them. Now they're coming outside and they don't recognize the same city that they left two years ago.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, does that apply to you, if you've been indoors a lot over the last two years but have started to come out more recently? Do you feel like you don't recognize the city that you left as you returned? 212 433 WNYC. If you've experienced crime or a new fear of crime or not, how's Mayor Adams doing as a self-described wartime general, in your opinion? If you're homeless or if you're not, how's Mayor Adams doing as a self-described wartime general, in your opinion, or what questions do you have about his policies for our guests, Elizabeth Kim from WNYC Gothamist and Juan Manuel Benitez from NY1 and NY1 Noticias? 212 433 WNYC, 212 433 9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer as Mayor Adams hits the three-month mark today.

Let's stay on crime for another couple of minutes before we talk more about the homeless encampment sweeps. Juan Manuel, the city council hearing yesterday on the first few weeks of the neighborhood safety teams was pretty rough on the NYPD officials who were testifying. There's concern, of course, about police violence, potentially, from these teams based on history or previous such teams. There's concern about arrests of many Black and Latino young people for not much, based on history.

A concern was expressed yesterday about all that risk in pursuit of not much reduction in gun violence from the effort. NYPD official, Kenneth Corey, defended the results as not just performative by saying they've gotten 20 guns off the street after just these several weeks of these teams being deployed. How should we understand that number, 20 guns off the street this month? Is that a lot, or is that a little, considering how many guns there are in New York?

Juan Manuel Benitez: Well, that might be too few right now. Obviously, there's way too many guns on the streets right now in New York City and the police department obviously has a really tough job now trying to retrieve all those illegal guns. It's really important to remember that Eric Adams won the election with the support of working-class New Yorkers, many of them Black and Latino, who really felt that the city needed to be better policed. Now, when we talk about those communities, and Eric Adams talks about those communities, they do want more policing, but they want better policing. What they don't want is unfair policing.

It's obviously understandable that when we talk about more aggressive police tactics, many in those communities get a little scared, and most of them Black or Latino men, because historically, every time the NYPD has been more aggressive when tackling crime, the number one victims of that aggressive policing have been Black and Latino men. It's going to be an extremely hard job to Mayor Adams to balance all those things out so we have a safer city without having to harass many innocent New Yorkers.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call. Well, actually I'll read a tweet first. It says, let's see, the mayor needs to focus on the underlying causes of these issues. Do we provide communities with the programs, support, money to survive and thrive? Liz, that's such a big question because Mayor Adams came in saying he was going to be the both and mayor. I'm just staying with a crime for a minute, but we can use this to pivot to your article today on the encampments of homeless people.

The both and Mayor, where he was going to crack down on crime, but also try to staunch what he calls the many rivers that feed into crime. We're hearing a lot about the crackdown part. I don't know if we're hearing much about the rivers.

Elizabeth Kim: Yes, I think that the reason for that is something like expanding summer youth employment. First of all, that's not going to even start until the summer, but to see the dividends of something like that is not going to be immediate. It's not like he hasn't talked about these other root social causes, he has. His expansion of the summer youth employment program was widely praised by advocates, but then again, the problem right now that he's looking at is what I just said, 45% increase from last year in major crimes. I think that is part of the reason why his rhetoric is focusing on policing because that also feeds into what Juan was talking about, this perception.

It's also this perception that he's taking care of it and you really see it dramatically in how he's talked-- He's started off, when he entered office, talking about compassionate policing. More and more, now you hear him talking about the NYPD is going to go after fare evaders, for example. I think that explains, it's not that he isn't paying attention to those things, but I think he feels that there's not enough that he can say or do in those other arenas that will help New Yorkers feel safe on the subway like this week, next week, next month.

Brian Lehrer: Report from the front, Luthra, a cab driver in Manhattan. Luthra, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Luthra: Good morning, Brian. These last three months, I pick up the passenger. No reason they make trouble. In September, $48, I took the job in Utica, Brooklyn. These two girl did not pay me. The cop was across the street. He did not help me. He said, "Sorry, you call 911." If I call 911, or you here next to me, you're not helping. Last September, that was Blasio. The city put the gutter in Blasio [unintelligible 00:16:16] Adam is just right now three months, it's going to take time, but who put the city in the gutter, that's Mayor Blasio. He put the city in the gutter. Not for everyone, for car driver it's very hard too. Three fares without pay that I did not get the money. $48, $12, $10.

Brian Lehrer: Do you tie the fact that the police officers on that scene did not help you, if I'm understanding your story correctly, do you tie that fact to something about Mayor de Blasio's policies?

Luthra: Yes, that was Blasio's policies. That was September. Seven months ago. He say, "You should call 911."

Brian Lehrer: You're tying that back to the mayor. I'm going to go on to another caller. Luthra, thank you very much. Maria in East Williamsburg, you're on WNYC. Hi, Maria.

Maria: Hi, how are you?

Brian Lehrer: Good. What'd you got?

Maria: I wanted to call and to say I took the subway home from work last night. It wasn't even 8:00 PM and I felt terrified. I think just with so many people wearing masks, head to toe, sunglasses, someone was doing pushups, pullups on the bar in front of my face with their knees in my face. It feels like there's nothing to do in the moment. I feel much safer. I live very close to public housing in East Williamsburg, and once I'm on the subway and in the city, that's when it gets scary, which is just so messed up.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. Maria, thank you very much. Juan Manuel, you want to comment on that? Does your reporting as you go around the city indicate that a lot of people might feel pretty safe on the streets in their neighborhoods, but less so when they get on the subways?

Juan Manuel Benitez: I think we need to acknowledge, Brian, that in the city right now, we have a housing crisis, we have a mental health crisis and an addiction crisis. Those three crises, the place where you see them the most is in our subway system, because for the last two years, the subway system emptied it out because many New Yorkers weren't going to work, weren't taking public transportation. Now when New Yorkers go back to the same living that they had before the pandemic, they're facing those issues.

That's what people are seeing on their commutes sometimes. Then let's acknowledge also, Brian, that we always talk about income inequality in the city and I think the pandemic just widened that gap of income inequality, but it's not only income inequality, we're talking about job inequality, housing inequality, we're talking about access to education inequality, medical care, and mental health inequality. Unless all those issues are tackled in a meaningful way. We are not going to see the seed of recovery long term.

Brian Lehrer: We'll continue in a minute with Juan Manuel Benitez and Liz Kim and your calls. We'll move on to Liz's article this morning with that shocking statistic. Adam's homeless sweeps have hit hundreds of encampments. Only five people have accepted shelter, stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue to take stock of Eric Adams' first three months in office as they come to an end today and as he called himself the other day, a wartime general. Taking your calls, 212 433 WNYC, taking your tweets @BrianLehrer, with Juan Manuel Benitez from NY1 and Elizabeth Kim from us. Liz, your article today on Gothamist, Adams' homeless sweeps have hit hundreds of encampments, only five people have accepted shelter.

First, in comparison to the just 20 guns getting seized after weeks of the neighborhood safety team deployment that we talked about in the last segment, you report the city has removed 239 of the 244 encampments in Manhattan. That is some very fast, very concentrated work. Can I ask, what do they define as an encampment?

Elizabeth Kim: An encampment is basically a structure that someone is using to live in. It could be a mattress, it could be a tarp, it could be a tent, or some people describe them as camping setups.

Brian Lehrer: How do they break them up? What happens during one of these sweeps?

Elizabeth Kim: What's supposed to happen and what the city officials say happens is that they first post a sign. They locate the encampment and then they post a sign saying that city officials are going to come on such and such date and we are going to remove this encampment. They're not supposed to just spring it on people and just arrive and then ask these people to leave. There's been a lot of disagreement as to whether that policy is being followed through.

My colleague, Gwynne Hogan, she's been out on the streets watching and interviewing people who've had their encampments removed. There are a lot of people who say that-- There was one person she interviewed yesterday where they were told that city workers would come on Friday, and instead, they came yesterday. It's not clear that the city is really following its own timeline on this.

Brian Lehrer: Your article describes a moment in the East Village where sanitation workers had just finished throwing out the belongings of a homeless person who had been living in a cocoon of tarps on 1st Avenue. They throw out people's stuff?

Elizabeth Kim: They do. That's been a real source of concern for the advocates and also a lot of heartache for the people living in these encampments. The mayor was asked about this very issue at yesterday's press conference. His argument was that a lot of these belongings are either soiled or-- They're also saying that they do give individuals time to collect their belongings, but we've heard from some people that they were given like an hour. An hour to basically grab all the stuff that you need, and for many people, it's not enough. It's a very traumatic experience. The mayor himself, at his press conference, he had a before and after picture of what an encampment looked like, and it was a lot of stuff, and then he had the after picture where all of it was completely removed.

Brian Lehrer: Jason in Queens, you're on WNYC. Hey, Jason.

Jason: Hi, thanks for taking my call. I don't think that Mayor Adams is doing enough at all. In fact, my sister moved here from another city last month and her biggest fear coming to New York was the crime. Last week, she was punched in the face on a train by a homeless man and chased and spit on. I would suggest, if the mayor is listening right now, if we could start a movement, if there could be a petition online, that he should have something called Operation Safe Subway, which consists of a city-sponsored group of people, maybe they're volunteers, that are equipped with communications, that are positioned on every single train in the city and every single station. They act as a deterrent.

There needs to be a massive initiative because this is an emergency right now, but I think putting it on the NYPD, I don't think they have the numbers. I think there should be something in the spirit of the Guardian Angels but sponsored by the city where every single subway and car is equipped with people that can act as a deterrent. I want to see something like this because things are getting worse.

Brian Lehrer: Jason, that's terrible what happened to your sister. Let me press you on one point, though. You said that she was punched by a homeless man. Homeless people get stigmatized as potential criminals more than they really are. How do you know the guy was homeless?

Jason: He wasn't dressed fully, he was partially unclothed according to the description, wasn't wearing shoes, hadn't bathed, and was sitting in a pile of luggage or clothing, which suggests he was transient, he didn't have a place to live. Thankfully, the people on the train sheltered her and protected her, and she was able to get out. We can't have a city like this. We cannot have a city like this. This can't be what New York becomes.

I would like to suggest, again, a huge initiative on the city called Operation Safe Subway where the subways are patrolled by volunteers, maybe they're all wearing the same color T-shirt, and it explodes on social media, and people are equipped not with guns and weapons, but walkie-talkies. People can just communicate to each other and signal the police if they needed. We need to feel like we're fighting back at this point because it's getting very dark.

I also want to make one other point, is that this seems to be happening at night, early evening into the middle of the night. Every morning I wake up, I turn on the news, there are horrible stories about things that are happening at certain times of the day. It seems to be happening early evening into the middle of the night. That would be the time that I would suggest deploying an initiative like this. Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Jason, thank you very much for your call. Juan Manuel, is that the first you've heard of any proposal like that? Here's a guy who obviously had a traumatic experience with his sister getting punched on the train randomly, it sounds like, and wants to mobilize fellow New Yorkers.

Juan Manuel Benitez: I feel for Jason and his sister. I think it's terrible what happened to her. I think we've all heard similar stories in the last couple of years happening in the subway system. What I'm not quite sure about is whether we need a group of vigilantes patrolling the subway system when we have a police department with about 50,000 people working in it, and we are spending, more than 5 billion people, on keeping New York safe. Obviously, we have to do a better job providing safety to all New Yorkers.

At the same time, we're dealing with an extremely complicated issue. We are not talking, from what Jason was describing, about some sort of a criminal, we're talking about, most likely, and I'm assuming here, I'm making an assumption, a person with some mental health issues. That's what I was talking about before. We do have a huge crisis, a mental health crisis in the city. When we talk about Liz's story about 5 homeless people accepting shelter out of more than 200 encampments, that is alarming. That shows you that those homeless New Yorkers who are going through a lot right now, they don't feel safe in the city's shelters.

The city needs to come up with a plan B because it's alarming that you're removing all those people or you're trying to remove all those people from the streets, but then, where are they going? They might be going to a different spot in the city, and you're not really solving the issue. The issue is that many of these New Yorkers need a lot of help, and not only housing, but they also need medical and mental health services. Is the city ready to provide those services and to spend the money to provide all those services for all New Yorkers who need those services?

Brian Lehrer: Liz, talk about that other headline stat in your article. 239 encampments busted up just in Manhattan, just since the middle of this month, only 5 people have accepted shelter. Why?

Elizabeth Kim: Basically, just like Juan Manuel said, people don't feel safe going to the shelters. This has been a perennial problem that did not start under Mayor Adams. Almost every New York City mayor, going back to at least Mayor Koch, has had this issue where it's very difficult to convince people who are on the streets to go into a shelter. They don't have good experiences there. A lot of times, they don't get the services that they need.

What Mayor Adams said, and he was the one that actually introduced this statistic at his press conference, was that he believes that they can build on that number, because the city launched a very similar program in the subways last month, and in the first week they got 22 people to accept services. They say that since that time, they've gotten over 300 people who were sleeping in the subways to accept services. Although it's not clear, are they still at shelters and are they saying there, are they continuing to receive services? I think we need to interrogate that number a little bit more.

The mayor thinks that, listen, he said, "This is the first couple of weeks. Give us time to build trust." The city has put out a pamphlet of what some of the new shelters look like in hopes of convincing people to come in.

Brian Lehrer: What they call Safe Haven Shelters, is that the terminology?

Elizabeth Kim: Correct. Safe Havens are basically, and this is not a new concept too, Safe Havens are shelters that generally have lower restrictions. Think about things like curfews or maybe certain rules. The most desirable thing about Safe Havens is the idea that you can get medical services on-site, you can get mental health services. There's a variety of what they call wraparound services. On top of that, a lot of Safe Havens have traditionally offered private rooms.

If you talk to advocates, the idea of a private room and the idea of getting some help with mental health or addiction, that's what makes a Safe Haven successful and desirable. The question is, though, again, this is not a new concept, they have been around. It was also not clear yesterday, how many of these safe haven beds would be in private rooms. That was a question I put to the mayor yesterday, and they weren't able to answer that. They say that they're going to have 350 of these beds available.

It's an ongoing conversation and it's about establishing trust too, with people who don't trust government services. I don't know that it happens on a dime. I don't know that it happens in a day, a week, or even months.

Brian Lehrer: 350 beds of this type, several thousand people living on the street. Why is it so hard to scale up? For all the talk in Albany about rolling back bail reform, for all the talk in the city about neighborhood safety teams, "cracking down", why isn't there more talk about scaling these things up really quickly?

Elizabeth Kim: One answer is nimbyism. Mayor de Blasio had a plan to expand Safe Havens in every single borough, and what he got was fierce community push back because nobody wants a Safe Haven in their neighborhood. Everybody wants to have these services offered to people who live on the streets, but nobody wants it in their neighborhood.

Brian Lehrer: Carlos in the Bronx, you're on WNYC. Hi, Carlos. Thanks for calling in.

Carlos: Hello, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Carlos.

Carlos: Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: I can hear. Can you hear me?

Carlos: Yes, I can hear you.

Brian Lehrer: You're on the air. Go ahead. What'd you got for us, Carlos?

[crosstalk]

Carlos: Brian, where is my holistic Mayor? He said he was going to be the holistic mayor and I loved him for that. I still have faith in him, but I am not seeing the holistic Mayor in action. I am seeing more of a military cop Mayor. Case in point, I witnessed an operation of this type at an encampment by chance. I was walking over the bridge at Gun Hill Road and Williams Bridge Road right at the Barnes river, and I saw that there was a woman looking over the bridge. I said, "What's going on?"

Three or four cop cars, seven police officers, three or four park rangers, and about eight parks department people cleaning up. I said, "What's going on?" She said, "They're busting up that guy's homeless where he lives, that homeless guy." It was a military operation, Brian, this was not a holistic operation. Look at the resources being expended on this. I'm talking about two cruisers, seven or eight cops lounging around watching that the guys didn't get violent, I guess, three or four park rangers, I guess because it's in the purview of the The Bronx Park, and eight or nine parks department people, cleaning up the debris that this guy has.

This guy, I happen to live in that area, has been living there for years. It's his place. He's not hanging out in the subway slashing people. Where is he going once this operation is done, and where are the services that would entail a more holistic approach?

As far as I could tell, there were no mental health people, homeless advocates, counselors that were going to guide this guy to the next step so that he could be one of the five that took him up on the offer of a shelter. He's just going to go find another place in another park, or somewhere under another bridge, under another tunnel to live because he doesn't want to live in the shelters. I need my holistic mayor.

Brian Lehrer: I hear you, Carlos. Stay there for a minute, Carlos.

Carlos: A holistic mayor that looks at [unintelligible 00:35:50] Sorry?

Brian Lehrer: Stay right there, I want you to react to this, because here's a clip of police commissioner, Keechant Sewell, yesterday, talking about the breaking up of these encampments, but portraying what they're doing as holistic. Listen.

Keechant Sewell: Homelessness has its root causes, but our response must be clear. When we see a problem, we must do everything we can to fix it. We must ensure that our public spaces are safe, that they are accessible to all, and that everyone in need of a suitable place to stay has access to one. In close partnership with the mayor's office and all of the agencies represented here today, we are focused on improving the quality of life of all of the people we serve, especially our city's most vulnerable populations.

Brian Lehrer: Carlos, what do you think when you hear that? It sounds like she's trying to walk that line saying, public spaces have to be safe and accessible to all, that's the breaking up of the encampments, but also everybody who needs a suitable place to stay needs to have one.

Carlos: I agree with her in principle, and I think it's the right message to be sending out because it's what people want to hear, but I don't think the mathematics are proving that she's correct, or that the mayor is correct. If it were holistic and there were some kind of advocates that had experience communicating with the homeless, we might have a better ratio of, what is it, 244 to 5?

Brian Lehrer: Yes.

Carlos: That's not good mathematics.

Brian Lehrer: That's the number of encampments. If you figure multiple people per encampment, there's probably at least four people in order to call it an encampment. That's at least 1,000 people.

Carlos: No, not necessarily. [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: It could just be a few people, but they've erected their stuff. Carlos, I hear you. Carlos, call us again. Thank you very much. I really appreciate your report from there. Liz, what about that number just to land where Carlos and I finished? If it's 239 encampments, and that's just in Manhattan broken up, that's not even the one on Gun Hill Road that he was just talking about, how many people is that?

Elizabeth Kim: I think the mayor was asked that question yesterday, and I don't know or I don't recall what the answer was to that. It can be anywhere from one person to, like you said, it could be four or five people living in a tent.

Brian Lehrer: We will leave it there, as the conversation continues about the Adams administration and the quality of life for everybody in New York City. We thank Elizabeth Kim from WNYC and Gothamist, her latest article, Adams' homeless sweeps have hit hundreds of encampments. Only five people have accepted shelter. Liz, with her colleague, Gwynne Hogan, wrote that together, and Juan Manuel Benitez from NY1, and host of Pura Politica on NY1 Noticias, their Spanish language channel, thank you both.

Elizabeth Kim: Thanks, Brian.

Juan Manuel Benitez: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.