Men Are From Mars, but Could There Be Intelligent Life on Venus?

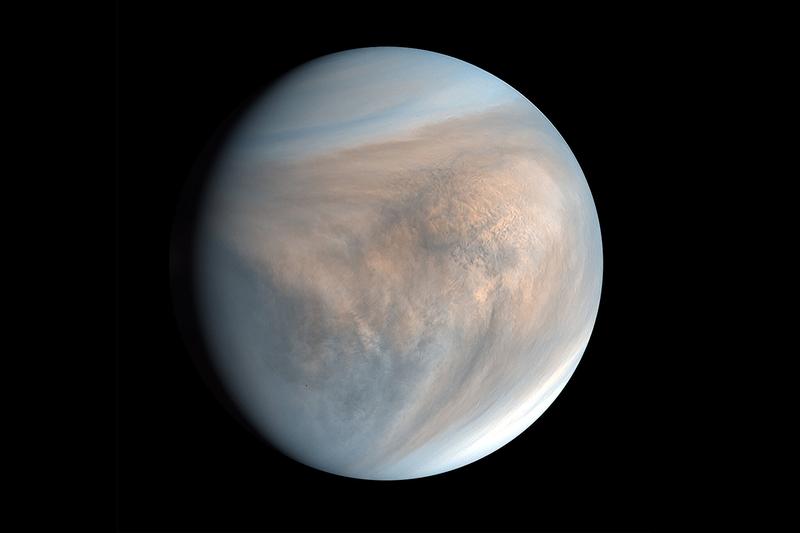

( PLANET-C Project Team/JAXA )

Male Speaker: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC this week, the world learned of an exciting discovery. Phosphine one of the galaxy's most odious substances has been detected in the atmosphere of Venus. Phosphine exists on earth, you can find it in sewage, plants, swamps, and your intestines. I know yuck, right? Here's the thing, as those examples indicate, phosphine is associated with life, especially with organisms living in oxygen-poor environments.

You've seen the headlines probably this week, so could this report of phosphine on Venus also mean that life exists there? Should our science fiction literature stop with all the Martians and get with the Venusians, or are there other explanations? Here with his, is science reporter for the New York Times, Kenneth Chang. Hi, Kenneth, welcome back to WNYC.

Kenneth: Hi, good to be here.

Brian: The finding was reported in a pair of papers released Monday. I see one, I think from Nature Astronomy and the other coming out of MIT, what did the papers report exactly? How was the phosphine detected and how much is there?

Kenneth: You can detect various gases on other planets by looking at what kinds of light get absorbed by these molecules. In this case, there was one wavelength of radio waves that have absorbed right at the wavelength that phosphines absorb light, so that was pretty unambiguous. It was a pretty big dip in the light at that wavelength, and they said it's up to 20 parts per billion of phosphine, which doesn't sound a lot, but it's actually thousands of times more than what's on earth.

Brian: What makes phosphine associated with life exactly?

Kenneth: On earth, as you were saying, it's been found in all these environments that are associated with life. It's actually been also found on Saturn and Jupiter and those cases, we know that it's not going to be associated with life, but those giant planets have, they're really hot and they have really high pressure, so in those cases, you can jam the phosphorus and hydrogen atmosphere to create that. On a smaller planet like Earth or Venus, there's not enough heat and there's not enough pressure to form phosphine, at least in the ways that we know how to make it. That's why this paper's suddenly so interesting.

Brian: The authors of the papers, if I'm reading this right, seem pretty confident that this means there is some kind of life on Venus, no?

Kenneth: Well, basically they've said we've looked at every possible way we can make phosphine and none of them can make as much as we see in the clouds of Venus. Therefore, what's left is the one thing we know that can make phosphine, which is anaerobic organisms. On the other hand, Venus is very different from Earth, and phosphine isn't a gas that a lot of people study, so maybe there's some chemistry that we don't understand, either in the rocks with Venus or in the atmosphere that is somehow creating phosphine in a way that no one has quite thought of yet.

Brian: Listeners, your questions on these three words, phosphine, Venus, life, for New York Times science correspondent Kenneth Chang 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. I guess we should ask in this case, even if it leads to this, what do we mean by life in this case?

Kenneth: Obviously, it's not going to be a Cloud City like in Star Wars, it'll be microbes. Probably one-cell organisms that are literally living their entire lives in the clouds of Venus because the surface of Venus is very harsh. It's more than 800 degrees Fahrenheit. It's got a pressure of 1,300 pounds per square inch. That's compares to 14.7 pounds per square inch on earth. That's like being crushed at 3,000 feet below the surface of the ocean. It'd be really hard just imagine anything living on the surface, but perhaps in the past, Venus was actually a nicer place, and life actually rose there and then migrated upward into the air as it became less hospitable.

Brian: Migrated up into the air, so what does it mean that the phosphine was detected in the clouds versus the surface of the planet?

Kenneth: Well, Venus' atmosphere is so thick that they actually couldn't make measurements at the surface. They looked as far down into the atmosphere as they could, which was, I believe tens of miles up in the atmosphere and this is an environment that is not too harsh. They're pressures similar to what's at the surface of Earth, the temperatures are 80, 100 degrees, so it's not that harsh. Other hand, this is also where the clouds of sulfuric acid are. Obviously we wouldn't necessarily like that, but organism on earth have evolved to live in highly acidic environments. Presumably, life in Venus, if it does exist, could have adapted as well.

Brian: How about a little more on phosphine? Like it's a really dangerous chemical, right? Didn't even have a cameo in breaking bad where Walter White used it as a poison?

Kenneth: Yes, he was being chased by a couple of bad guys. He managed to synthesize it in his lap and kill off the bad guys. Although, it's probably not quite that easy to make in real life. It pops up here and there, but actually not very many people study it in-depth, so it's scary even among chemists and therefore, that's why people are skeptical because there's a lot, people haven't looked at it.

Brian: Is there any other reference to phosphine in pop culture that you know of I don't?

Kenneth: I don't, I guess I haven't watched enough TV lately.

Brian: Is there a lesson about climate change embedded in Venus's atmospheric evolution? As far as we know, it's not like humans caused Venus to go from a lower temperature planet to one thick with CO2 and acid rain.

Kenneth: Well, I guess the one lesson from Venus is that its proof that carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas. Obviously, humans did not create all this carbon dioxide that is now about 97% of the atmosphere of Venus, but it shows that carbon dioxide does trap heat and can actually heat up a planet to hundreds of degrees. Recent research actually indicates Venus might've been much nice up to relatively recent and that means 700 million years ago, which is recent for astronomers and planetary scientists, since this whole system is four and a half billion years ago and it's only there for various reasons.

Perhaps from volcanoes, perhaps from other changes on Venus that cause carbon dioxide to build up and it's now created such a hot planet there.

Brian: That's actually pretty big for the political conversation on earth, I would think. You're a science reporter so you check me on this, but the people who try to deny the reality of climate change, they can't deny anymore that the earth is warming, because we're having our record global temperatures year after year after year after year, so that's definitely happening. The only thing they could say is, well, this isn't being caused by all the emissions of human beings, primarily CO2 over the last century or so, but if there's indications from independent evidence, like from another planet, that CO2 causes warming, then that settles that.

Kenneth: Well, I guess the science of the carbon dioxide, even though people who are arguing against anthropogenic climate change, will agree that carbon dioxide has been increasing in the earth atmosphere for the last 100 years, and they probably accept that in the laboratory, carbon dioxide does act as a greenhouse gas. They're just saying that over the history of earth, there's been bigger cycles changes and therefore, whatever we've done now is relatively small and there could be other contributing factors, perhaps the sun, perhaps something else that are leading to the magnitude of change we're observing now or that the magnitude change we're seeing now isn't as supported as we think it is.

Brian: Jan in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jan.

Jan: Hi. I have a question about these clouds of Venus. I just heard recently that Venus is the most reflective planet because of the nature of the clouds. The clouds reflect more light back to the sun than any other planet and in fact, speaking of the greenhouse effect, the same astronomer said that if it weren't for all that carbon dioxide on Venus, creating such a greenhouse effect, Venus would in fact be colder than the earth because of all that reflectivity, even though the Venus is closer to the sun. It is in fact the carbon dioxide that makes it 900 degrees. My question is, is there anything in the clouds, the same feature that causes this unique reflectivity, is there any relationship between that and the possible presence of phosphine?

Brian: Interesting question, Kenneth.

Kenneth: I don't know the details of that but it does make sense because at this high altitude on Venus, the temperature is much cooler, about 80 to 100 degrees or so. That's partly because a lot of heat is being reflected away. That probably does play into the exact temperatures that exist at that altitude.

Brian: Jan, thank you very-- Go ahead, did you finish an answer, Ken?

Kenneth: I haven't done the calculation so I don't know particulars, but it does make sense.

Brian: Venus is the next closer planet to the sun. People do know the old mnemonic device my very energetic mother just served us pizza for the initials of the planets. Mercury, Venus, energetic, Earth, mother, Mars, just, Jupiter, serve Saturn, us Uranus, pizza, Pluto, but Pluto is no longer a planet, so it's just my very energetic mother just served us. Is Pluto a planet again? Have they figured that out?

Kenneth: It is still not a planet. They describe it as a dwarf planet but that doesn't count as among the major planets.

Brian: I think Trump is running on Make Pluto a Planet Again. I'm kidding. Gregory in Manhattan you're on WNYC. Hi, Gregory.

Gregory: Hi, Brian. Thank you very much for taking my call. Listen, you guys, you're a great man. Thank you for your service to us.

Brian: Thank you.

Gregory: I have a question that's been bothering me because I've been a science fiction freak for my whole life like. Are we going to finally start looking at other forms of life that have nothing to do with carbon?

Kenneth: That's always something that science fiction writers has thought about. It was in a Star Trek episode from way back when. The problem is we don't know what that would look like. I guess the obvious thing you would think about if it was not carbon, it would be silicon, which is just right underneath it in the periodic table. I guess, as some other sciences have pointed out, we have a ton of silica on Earth. It's all of our beaches, and that's not what life decided to use. It decided to use carbon.

It's possible elsewhere that it could be, but we don't have instruments to figure out how to detect that right now. It'd be great if we found that, something like that, but we need to know more before we know what to look for.

Brian: By the way, correction. I left out Neptune and it was nine. It was my very energetic mother just served us nine pizza pies, so Neptune, my apologies. Shea in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Shea.

Shea: Hi. This is an amateurish question. I'm an artist and not a scientist, but I'm curious. Has phosphine made an evolutionary contribution to its development and its growth? If it's also found inside people, has it had any significance in its existence, on an evolutionary development?

Brian: What a wonderful question. If phosphine has survived all this time does it have an evolutionary function?

Kenneth: We don't know. That's actually a great question. I think a lot of biologists are now going to be a lot more interested in phosphine than they have in the past. As you've mentioned, phosphine have been discovered in these environments that are associated with life, such as sewage plants and your intestines. However, no one has yet isolated the microbe that produces phosphine or figured out how any microbe can produce phosphine.

We don't understand the whole biochemical machinery that produces this molecule, which is-- there's a lot to be studied here. If this is actually something that's prevalent on Venus, then this is going to suddenly become a very interesting area of research and there's a lot of unknown, a lot of questions where the answers are not yet known.

Brian: One more, David in Oyster Bay. David, we have like 15 seconds for you, Hi.

David: I got it. I have a simple question, which is what constitutes life in any atmosphere?

Kenneth: Life is generally thought of something that reproduces, has a metabolism, so it can actually do things. A cell, you can tell, a bacteria can reproduce into more bacteria. We can have children, as opposed to a piece of rock, it only falls apart and that is not alive.

Brian: I thought we needed a philosopher to answer that question, what is life, but you did it as a science correspondent, and you did it so efficiently that I'm going to throw in one other quick question. Give me 30 seconds on this. Your other recent article, A Solar Forecast, and now the weather. A Solar Forecast With Good News for Civilization as We Know It, what does that mean? Literally 30 seconds.

Kenneth: The sun has 11-year cycle in sunspots, we're right now at solar minimum, which is the quietest period. There's a forecast from scientists that says the maximum is going to occur in five and a half years or so, though it looks fairly calm, which means there's less chance of giant explosions that will come off the sun and possibly hit earth. If a giant one did hit us, that could take out the power grids, and the satellites, and cause lots of problems. That's hopeful that it won't be as bad.

Brian: Unless Iran does it through a cyber attack, but one less thing to worry about. Kenneth Chang, science correspondent for The New York Times, thank you so much.

Kenneth: Thank you.

Brian: The Brian Lehrer Show is produced by Lisa Allison, Mary Croke, Zoe Azulay, Amina Srna, and Carl Boisrond,with help on our Daily Politics podcast from Zach Gottehrer-Cohen, and that's Juliana Fonda, and Liora Noam-Kravitz at the audio controls, in-person, at the WNYC studios. Thanks so much for listening today, I'm Brian Lehrer.

[music]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.