The Legal Aspects of Jordan Neely's Killing

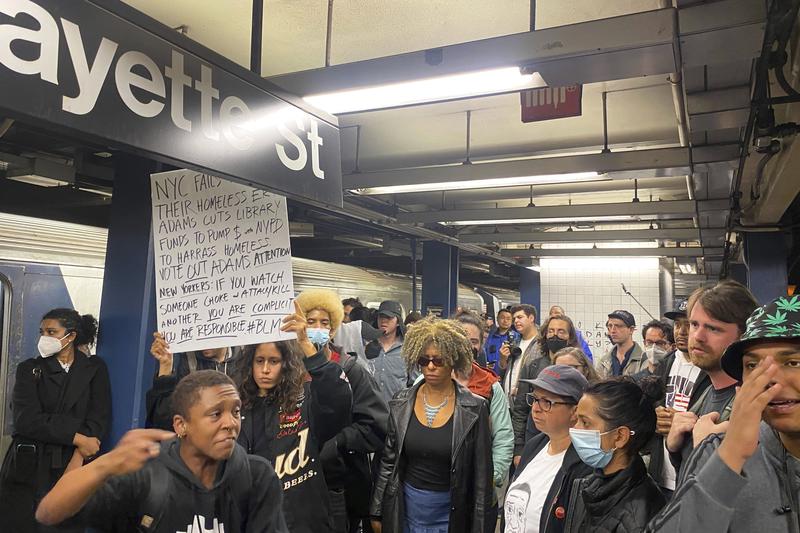

( AP Photo/Jake Offenhartz / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. It was one week ago today that Jordan Neely was choked to death on that F train in Manhattan. The Manhattan DA is apparently still deciding if the choker will be charged. We now know the identity of the choker, 24-year-old former Marine Daniel Penny, originally from West Islip on the south shore of Long Island.

There were developments over the weekend, including protests and pieces of evidence emerging and Mr. Penny hiring as a defense lawyer, who else but the Republican who ran against Alvin Bragg for Manhattan DA? The lawyer's name is Thomas Kenniff. The lawyer released a statement over the weekend that said, "Daniel never intended to harm Mr. Neely and could not have foreseen his untimely death."

Could he have? A bystander video emerged over the weekend of someone warning Penny that he was killing Neely. The person said, "That's one hell of a chokehold. You're going to kill him." ABC News reports DA Bragg has interviewed six people, but wants to interview four more. The statement from Penny's lawyer also says, "When Mr. Neely began aggressively threatening Daniel, Penny and the other passengers, Daniel, with the help of others, acted to protect themselves until help arrived."

One of the things at stake legally is what the standard will be going forward on the subways and elsewhere for physically attacking a person in a mental health crisis when they are making you scared by yelling, but not specifically threatening to hurt you, and not physically attacking anyone themselves. Remember, the witness reports in the press says, "Mr. Neely was apparently in a mental health crisis that had him yelling that he was hungry and thirsty and prepared to go to jail or to die and throwing his jacket on the ground."

The witnesses say they were scared, but Neely never attacked anyone. Here is the Reverend Al Sharpton at a weekend rally in Harlem on the standard that no indictment here would set.

Reverend Al Sharpton: I'm saying that this man needs to be prosecuted because what you will do if you do not prosecute him, in my judgment, is you will set a standard of vigilantism that we cannot tolerate.

Brian Lehrer: Reverend Al Sharpton. With us now, as we await the DA's decision is Errol Louis, host of The New York Politics Show Inside City Hall on Spectrum News NY1 weeknights at 7:00, and a New York Magazine columnist. Errol does have a new piece in the magazine about this case and the legal and housing and other issues that it raises. We also plan to touch on another big thing today in the legal system in Manhattan. Closing arguments in the E. Jean Carroll vs Donald Trump civil suit alleging rape and defamation.

If we have time, we may touch on the Rockland County Executive Republican Ed Day declaring a state of emergency and saying police will be ready. Why? Because Mayor Adams found a hotel in Rockland that will house 340 migrant men of the tens of thousands in our area seeking shelter as they apply for asylum. Errol, always good to have you in pretty intense times. Welcome back to WNYC.

Errol Louis: Always glad to be with you, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: I want to ask you to put your lawyer hat on. People may know you as a journalist, they may or may not know that you're also a lawyer, and discuss the legal status of the Daniel Penny case. It was a week ago today that he killed Jordan Neely. Why is it taking Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg this long to decide whether or not to charge Penny with a crime?

Errol Louis: That is a very good question. The investigation is going to have to be as thorough as they can make it on short notice, and they're going to try and find literally every single person who was on that subway car. Every possible witness has got to be located, contacted, brought in, and interviewed to try and find out if all of what we think we know from a snippet of video and a handful of interviews by one or two eyewitnesses, see if it's all telling the same story.

Because if it's telling wildly different stories and we don't know what happened before that video that got posted and we don't necessarily know what happened after, and we didn't hear every conversation that was happening during all of those tragic events. If the stories don't line up, and it doesn't look as if they can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a crime was committed, then they will not indict Daniel Penny or anybody else.

There are other questions, though. I mean, there were multiple people that were holding down Mr. Neely in his death agony, and there get to be questions of accomplice liability. Did those people know each other? Did they communicate with each other? What did they think they were doing? It really gets complicated very quickly. I think that's what you're seeing right here, that you've got to really be methodical and professional, and Alvin Bragg prides himself on being both of those things.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, your questions or comments about the killing of Jordan Neely by Daniel Penny and as Errol reminds others who were involved in pinning him down as the chokehold was ongoing, your questions, legal or otherwise, 212-433-WNYC. Your comments are welcomed as well. 212-433-9692 so many thoughts and feelings and questions in this case, obviously.

Errol, could DA Bragg have the Jose Alba case in mind? You referred to that case in your article, and people may remember that in that case, a man named Austin Simon did physically begin to assault the bodega worker Jose Alba, and Alba stabbed him and Mr. Simon died. DA Bragg quickly charged Jose Alba with murder and then dropped the charges later after determining that he acted in self-defense. Bragg got a lot of criticism for charging Alba so quickly. Could DA Bragg be overcompensating with Jose Alba in mind?

Errol Louis: I think he is probably being a little extra cautious because of what happened in that case. In the Jose Alba case, we should all be very careful not to rewrite the history. I mean, the standard at the time, which I believe very strongly should be the standard, is under whatever circumstances, you don't get to stab somebody to death and then just have a five-minute conversation with the cops and go home. It doesn't work that way. It cannot work that way.

Jose Alba was detained for a very good reason. Based on what the cops knew at the time, they said, "Okay, we're going to have to hold you until we figure out what went on here." There was such an outcry, but that outcry happened immediately, Brian. Even before they had a cause of death before the medical examiner had even determined why Mr. Simon had died, there were people who were saying it's outrageous that he was held for even a minute, and that's just not reality.

When they had, I think, a better sense of what was going on, when they had conducted a preliminary investigation, then Jose Alba was allowed to go home with some constraints. I think he had an ankle monitor, and the city facilitated it. It normally takes a few days. They got it for him immediately so that he could go home and not remain in confinement. The standard in this case, people, I think, are asking, and they have every reason to ask, is it really true that you can choke a man to death and then tell the cops, "Here's my version of the story. I'm going home now," and everybody's okay with that?

That's not how it's supposed to work. People, I think, are very upset because it looks as if there's not just a double standard, but an unworkable standard. If you kill people of a certain class or perceived to be of a certain class, or, God forbid, race should be invoked here, and you get to just go home and have dinner, it's just like a crazy day on the subway, and you can tell your wife about it, it can't work that way.

Brian Lehrer: Your article noted how differently Mayor Adams has reacted to this killing compared to Jose Alba. Differently how?

Errol Louis: Look, when Jose Alba was first arrested, and again, there was this human cry, a few days later, I think it was about six days later, again, there had been no indictment. It wasn't clear what was going on. The investigation was still happening. I think they might have had a cause of death by that point, but the mayor went to the bodega and held a press conference and said that he pronounced the defendant in that case as honest and hardworking and basically said he was on his side.

Again, using words like honest and hard-working, utterly prejudging the case in a way that was not required at all. It just had nothing to do-- It didn't help the case forward in any way, shape, or form. Now, in this case, you have the mayor saying, "Oh no, we've got to wait. We've got to wait until the district attorney conducts his investigation, let's not prejudge it, and so forth and so on."

It's not just a wildly different standard. It also raises the question of why the mayor doesn't just maybe restrain himself as a policy and make that the policy and just say, "Look, I'm not here to prejudge cases. I'm not going to be running to crime scenes and calling somebody guilty or innocent. That's not my job." It seems more clear now. It definitely was not the standard that applied last year in the case of Jose Alba.

Brian Lehrer: Errol, the legal question, should Penny be charged with a crime? As the New York Times describes it, "Under New York law, a person may use physical force on another person if they have a reasonable belief that it is necessary to defend themselves or others. A person can only use deadly physical force if they have reason to believe that an attacker is stewing or about to do the same." I guess use deadly physical force. That language from the New York Times describing New York state law. That first part, "A person may use physical force on another person if they have a reasonable belief that it is necessary to defend themselves or others." It's one of those reasonable person standard things, will charges here, hang on whether DA Bragg thinks Penny had a reasonable belief that he or others were about to be attacked.

Errol Louis: Well, the charge will be based on whether or not they think they can prove beyond a reasonable doubt that something unreasonable happened. It gets a little bit stickier, Brian when you raised the question of deadly physical force, which is what bumps it up from negligent or manslaughter-type charges up toward murder. Where it starts to get sticky is that New York law also specifically says that once the physical threat has passed, you no longer have the right to use deadly physical force. I think they're going to try and evaluate. This is, again, why it's taking so long. They're going to try and evaluate the facts as they can determine them, line them up against the law, and see at what stage something might have gone from being unfortunate but legal to possibly illegal or even criminal.

It's very fact dependent. How many minutes? At what point did he hear the person saying, "Hey, you're killing him." Did he believe the person who said it? Who was that person? Why did he think that? It really gets very, very specific to the facts of the case. Once we know what the DA has and what he thinks he can prove, then I think, we'll see whether or not anybody gets charged. I know that there's a belief among a lot of your listeners, and I certainly emotionally feel this way.

Look, let's just put it in court, and let's figure it out along the way. That's not really how prosecutors operate. You don't turn a person's life upside down if you can't really expect to prove that they committed a crime. It's not just an abstract exercise. We'll see whether or not he's going to go that far. Of course, Mr. Neely's family apparently has legal representation, and they're going to seek whatever form of justice they can if not a criminal prosecution, then right behind that might be a lawsuit against the city or the MTA.

Brian Lehrer: Of course, they have to go through the investigation process. Would you agree that from what we know, based on what's been reported in the press of the eyewitnesses, including the guy, Mr. Vasquez, who's a journalist who filmed the first video that got out, according to what we know, Jordan Neely yelled that he was ready to die, that he didn't care if he goes to jail. He threw his jacket on the ground, but he didn't attack anyone. As far as we know, he didn't threaten to hurt anyone like, "I'm going to hurt you." He was just yelling about his mental state. From what we know, I don't know how we get to a reasonable person's standard thinking they were about to be attacked.

Errol Louis: Yes. Unfortunately, the governing law on this is People vs Goetz which already gives you a foreshadowing of what might go sideways in this whole exploration of the case. In the case of Bernhard Goetz, none of the four teenagers that he shot, and in one case paralyzed, none of them had ever laid a hand on him. All we had was his account saying that he felt threatened by them and that he thought they were going to mug him. In the end, a jury believed him. Bernhard Goetz ended up going to prison, but he didn't go to prison because he shot those kids. He went to prison because he had an illegal firearm. It's really important to keep that in mind.

When the Manhattan DA said he didn't think he could get a conviction in the case of Jose Alba because the facts didn't lead him to believe he could convince a jury beyond a reasonable doubt. I think that's partially an acknowledgment of reality. The reality is a lot of people think that feeling threatened, somebody being disorderly on the train, somebody saying they don't care if they go to prison or if they die, that's good enough. Any amount of force, including deadly force is warranted, or at least understandable. That in some ways what you're raising, Brian, is the critical question here. What kind of a society are we?

At a point, have we reached a point as we did in 1986 or in the '80s with Bernhard Goetz, as we did with Jose Alba last year, have we reached a point where enough is enough If somebody gets out of line to the point where people feel really scared, then anything can happen to them, including death and we're going to sanction that? You can hear from the way I'm talking about it. I don't think that's a particularly good way to go I wouldn't feel safe on the subways if that was the accepted standard. That's where a lot of people are coming from, and we should acknowledge that.

Brian Lehrer: Before we start bringing in some callers. I would go one step further down that Bernhard Goetz case analogy. Bernhard Goetz, the subway vigilante from the '80s, which might be a legal precedent here. A difference might be that in that case, from what we know, Goetz was surrounded by four young men who reportedly said, "How are you doing?" Asked for money and one bulged out of pocket to suggest a weapon. Goetz then shot them, and Goetz was charged and acquitted. That doesn't make what Goetz did. Okay? He was acquitted and that acquittal was of course, very controversial because he was not actually robbed or attacked, but there was at least the appearance based on that evidence I cited of a crime actually beginning to take place. Not as far as we know.

Errol Louis: It's interesting aside from the fact that I think that's his account of what happened. I don't think that's what Darrell Cabey and the other kids said, but also in this case, and this drives my wife crazy, so I want to make sure I make this point because she keeps reminding me of this. When we use the term vigilante in connection with the killing of Jordan Neely, there really was no crime committed. Feeling uncomfortable is not a crime. Throwing your jacket down on the floor of a subway and yelling is not a crime.

Brian Lehrer: Well, that's the premise of my question.

Errol Louis: Well, it's not a crime of any sort. It's not the question of whether the threat had to be repelled with deadly force. There was no crime committed. He's not a vigilante, he's something else. He's a person who killed another person. What he thought he was doing, we should ask him. Maybe he thought he was upholding civilization or something or saving other people from harm. He was definitely not upholding any law that I'm aware of.

Brian Lehrer: Steven in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi Steven.

Steven: Hi. How are you? [unintelligible 00:18:16] One of the things I heard there are a number of things here where issues come up, but one that heard particularly about the so-called offender is that he was a marine and he had to be recently discharged. He's only 24 years old. The question is, what training if any, did he have in the use of a chokehold in combat situations? Was he in a combat situation and could part of his reaction have been what he was taught to do in a military situation and that he reacted to that because there's a lot of those events that occur? I've seen a lot of veterans in my life and had a lot of interesting things.

One incident I'm aware of was a person walking down the street in front of the post office and was bumped into by another guy who had just been a marine, who had gotten out of service, who then proceeded to kill him immediately and was not prosecuted for that because of the post-traumatic stress reaction. We don't know that yet at least from the information that's come out in the news media. The other issue for me, that's important is was cited that the victim had been through the mental health system for maybe 40 times. Also that when he was 12 or 14 years old, his mother had been killed in what was considered a very brutal killing, and that he changed after that. I don't know what treatment he got, whether that treatment took into account the violent death of his mother, how that affected him in terms of his behavior, and whether there was a focus on the trauma. It seems likely that he was reacting to over this time, and whether there was a failure of the city and the mental health system for not doing something more effective about that and preventing him from getting in this condition.

Brian Lehrer: Steven, thank you for that call. Errol, Steven really raises the question of whether--Daniel Penny may also have had a mental health crisis triggered in some way by Jordan Neely's behavior that may have been some marine service-related PTSD. Of course, we don't know, but it's an interesting and relevant question to at least raise.

Errol Louis: Oh, no, absolutely. The expression hurt people hurt people. That's real. Somebody who we have specifically trained to go out and harm people. That you don't just flip a switch after they come home especially if there was any trauma involved. We'll see if that gets raised as a defense. I don't know that it necessarily will, but it is certainly relevant. As for the past trauma that we know about from Jordan Neely's life, it's horrific. It's something you wouldn't wish on your worst enemy.

His mother was brutally murdered by his stepfather. As a teenager, Jordan Neely had to go to court as a witness where he was cross-examined by the stepfather who was representing himself. It's just a complete nightmare. This is the backdrop of somebody who also had to struggle apparently with ADHD and suicide attempts, schizophrenia apparently. Just a horrible situation. When we have that pain walking around on two feet, it's a formula for exactly the kind of disaster that we've seen.

Brian Lehrer: To the point that the caller raises about the state of mind of Daniel Penny. Here's the lawyer for the Neely family, Lennon Edwards addressing that on Channel 7 on Friday.

Lennon Edwards: We have a civilian also who's really-- In my view, this is somebody who's a trained killer. He is an ex-marine and he understood the art of hand-to-hand combat.

Brian Lehrer: That's an accusation by the lawyer for the Neely family that Daniel Penny knew or should have known that the chokehold that he was applying and the length of time for which he applied it would have been not just an act of restraint, but the use of deadly force. That's got to be something that DA Greg is considering too.

Errol Louis: That's right. This is what lawyers do. He's moving some pieces on an invisible to the rest of us chess board and making sure that certain defenses are either foreclosed or signaling that he's going to attack those defenses, so right off the bat. This is foreseeable. You want to eliminate any possibility of mistake of Daniel Penny, for example, saying, "I didn't realize."

It's the analogous to, "I didn't know there was a rock inside the pillow. I thought I was going to just hit him with a pillow, and it turned out there was a rock inside and it did more damage than I expected." He's trying to take away that defense saying, “You knew exactly what you were doing.” They'll probably, if they haven't already started pulling up training manuals. What kind of training did you get? If indeed you had somebody in a chokehold for 15 minutes, what were you trained to think would happen at the end of that period? Those kinds of questions.

Brian Lehrer: Eddie in Queens, you’re on WNYC with Errol Louis from NY1 and New York Magazine. Hi, Eddie.

Eddie: Good morning. Good morning, Brian and guest. I would like to speak on behalf of myself and millions of other strap hangers that use the subway. All of us have gone through problems in our lives, but all of us want to use the subway with a degree of safety and civility. It's a tragedy that somebody should be killed on the subway. What irks me now is that this gentleman had 21 prior arrests, and now they're going to try to make a saint out of this guy. I don't think that's right. Again, I don't justify it. I feel sad. It's a tragedy. Nobody should lose their life on the subway but don't make a saint out of this guy. That's all I wanted to say and wish you both a good day.

Brian Lehrer: Eddie, thank you very much. Of course, nobody on that subway car knew anything about a prior criminal record of Jordan Neely. I don't think we're trying to make a saint out of him in describing the situation. Let's go on to another. Errol, I’ll tell you and I'll tell everybody. Our board is pretty well split between people saying things like the first caller said, and people saying things like the second caller said. Here's Yokasta in Flushing. You're on WNYC. Hi, Yokasta.

Yokasta: Hi Brian. There's a couple of very quick points. One of them is we are seeing the ramifications of what happens when you defund mental health. This gentleman should not have been on the subway in the condition he was in, to begin with. I am an individual with a disability. I have low vision and I'm also a special education teacher. There are people who will always need wraparound services. The idea that you can just forget about providing services to people who may need them for the rest of their lives is insane.

Some people will always need support, and this is what happens when people don't. We don't know if he needed medication. We don't know what type of support would've kept him from having the life that he did and from having all the prior arrests that he did. Had he had better mental health support, maybe we wouldn't see the situation. The second part of it is, I have a visual impairment. If I'm on a train and somebody is screaming, I can't assess the situation.

I would want someone to intervene because I'm scared. I don't know what's happening. I think we have to look at this really holistically. People really should reserve their opinion about whether the gentleman acted correctly or not in the chokehold until an investigation has been formulated. Past that, we really need to look at our mental health system. Straphangers should not be scared to be on trains. I'm petrified. It's the honest truth.

Brian Lehrer: Yokasta, thank you for your call. We'll get Errol's reaction to them in just a minute. Stay with us as we continue. Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Brian Lehrer on WNYC. As we continue with Errol Louis, New York Magazine columnist and the host of Inside City Hall on Spectrum News NY1, weeknights at 7:00. Errol to the caller we had on just before the break. Your article in New York Magazine uses some very strong language saying that Jordan Neely, because of his status in various respects was already socially dead. In the context of New York and the United States today, would you talk about that and say anything else you want in response to the last caller from Flushing?

Errol Louis: Sure. Many years ago, I took a course with a sociologist named Orlando Patterson who at the time had just published a book called Slavery and Social Death where he did a really broad survey across multiple cultures over a period of centuries. His particular focus was slavery. The point really was much broader, which is that in every society that he looked at, there were categories of people who were declared socially dead and they were subjected to all kinds of bad treatment, including violence.

It just reminded me of how we treat a lot of people in our city who are almost of a different caste, C-A-S-T-E where we treat them as if they're just not worthy of our time and attention or minimum amount of time and attention. Jordan Neely struck me as the kind of person that many people walk past every day. Where it dovetails, I think in some ways with what the caller was talking about, and I couldn't agree more is that there are tons of agencies that he came in contact with.

We have not managed to get those agencies to work in alignment or work rationally. It's alphabet soup. It's the MTA. It's health and hospitals. He was hospitalized at Bellevue multiple times. It's DHS, the Department of Homeless Services where he stayed in some of the shelters. It's the health department, which had the crisis outreach teams that dealt with him, I think five times in the last year alone. Ultimately, the NYPD who we send after all the other agencies have failed to do what they're supposed to do.

Of course, the Department of Correction. He was there at Rikers Island for about 18 months in about the most untherapeutic environment you can imagine. At the end of all of that, all of those six agencies, we have somebody who is destitute, homeless, disorderly, and deranged in public. How does that happen? That to me is the question that should be asked. Not whether or not he was a good guy, or whether or not people should be scared of him, or whether or not he belonged in jail, which we know had been tried in this case. I want everybody to remember that he was in fact, locked up.

If you think the answer is to lock him up, this is what we did up until February of this year, and we now saw what happened, not even 90 days later. We have a lot of questions to ask ourselves and to ask our government about how is it that in all those agencies I just named, I'm sure there's a record of who he spoke to, who dealt with him, what their plan was for him, and, and we should at least ask, can't we do any better than this?

Brian Lehrer: Lou on Staten Island, you're on WNYC. Hello, Lou. Lou, are you there?

Lou: Good morning, Brian. Thanks for taking-- Yes, I'm here. Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: Yes, now I got you. Go ahead.

Lou: What your guest just said is exactly what I was about to say, but I was just going to come straight up to the point. This whole thing was that boils down to [inaudible 00:31:22] [sound cut]

Brian Lehrer: Sorry, Lou, your line is breaking up so bad. I think we're going to have to go. One of the things that Lou may have been getting at there, Errol, is that the demographics here are much like those of the stereotypical police encounter in New York City, and ones that have made the news in various places certainly in New York where police violence is accused. Penny was white from the south shore of Long Island in Suffolk County, a former Marine. Neely was Black and homeless and in mental distress, arguably Penny saw Neely as more threatening than he was based on implicit racial bias, arguably. Where do you see race coming in?

Errol Louis: Look, it's one of several possible narratives. The overlapping layered levels of failure and blame here are almost impossible to disentangle. You could see this as a story of government incompetence. The six agencies I just ticked off that couldn't figure out the right way to deal with this person. There's a way to deal with it as a transit story. Our transit reporter at New York 1 ended up being one of the lead reporters on this because it happened in the subways. Is it an income inequality story? Why do we have so many poor people among us? Is it a mental health story?

Is it a race and race discrimination story? Is it a self-defense story? Is it just straightforward criminal justice? Everybody's got a different angle, but race and racism as an aggravating factor, I'm thinking, I don't know 5% of the 100% failure here. Could there have been bias involved? Possibly, but I think of that as not necessarily the most salient or important factor here.

Brian Lehrer: One of our guests last week though, said we could probably not name a case where the shoe was on the other foot, racially, where a white person was in some mental health crisis that appeared threatening to a group and a Black person took them down and the guy wound up dead and the Black person wasn't detained by the police.

Errol Louis: Well, that's true. Look, as a hypothetical, I don't think we could look in the archives and find that hypothetical. I think that's absolutely right. It says something about who we think is or isn't in the circle of lawful behavior and who is or isn't a protector. That's a broader conversation about people's changing attitudes. I don't think that that will be true forever, by the way, if you start looking at who runs our law enforcement apparatus, both the district attorney, the mayor, the police commissioner, the chief of the department. There are a lot of African Americans who are here trying to protect the public. I think people, if they're holding on to any lingering racial, or racist notions, I think the facts are going in the other direction.

Brian Lehrer: Evelyn in Mendham, you're on WNYC. Hi, Evelyn.

Evelyn: Good morning, Brian. Longtime listener, monthly sustainer. Always, always love your content and your show.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you.

Evelyn: At what point does someone decide to step in? Must we all just wait until that situation escalates to a point where Mr. Neely actually hurt somebody? Then does someone step in? Katie Genovese, wasn't she screaming for help on a New York City rooftop and no one stepped in to help her? At what point do we-- Must we all be passive until a situation escalates? I've taught self-defense to women. I've taken self-defense. Nobody steps into a situation where you directly encounter someone glibly. I want to support the Marine in this instance and say, I don't think he intentionally stepped in to murder someone, and murder is too intense a word. He was a protector. He was trained to protect.

If I was on that subway car, I would want someone to step in to protect me too, or I would be the one stepping in to protect. We don't enter into these situations lightly, and there's so much to unpack, and every single one of your other callers and your guests have brought up so many salient points about mental health, people in mental health crises. There's way too much to unpack to just simply point fingers and accuse this marine of murder. I don't think that's what we should be doing.

Brian Lehrer: Well, do you think that you, with your training as you just described it, or that you would want somebody with their training to have physically taken this guy down based on what's been reported that he was doing and wasn't doing at that point, you think a physical intervention was warranted at that point to get together with other riders who also participated in it and restrain the guy before he did anything?

Evelyn: If I were in that situation, yes, but you're also-- It seems like we're asking John Q. Public to be a therapist and the police and-- It seems like there's a man screaming in a car, in a subway car throwing his jacket around who steps in and deescalates. If there were a licensed therapist on that subway car, certainly they could have stood up and said, "Okay, let's calm the situation down," but you're asking people who are on their way to work, trying to mind their own business to suddenly become a therapist and deescalate a situation. This Marine was trained to do a specific thing, and he stepped in to do a specific thing. Was it wrong? I don't know.

Did he step in to protect the other people in the car because he thought that this was an escalating event? Yes. If there was a psychologist or a psychiatrist on the car, could they have done something different? Of course, but there was no psychiatrist on that subway car to my knowledge. There's so much that's involved in this, so much that could have been done for this poor young man that ultimately wound up dying and so many there-- No one on that train was trained in de-escalation. Must we all then take a course in de-escalating situations to save ourselves? I don't know. What's the answer?

Brian Lehrer: I'll ask you one more follow-up question, which is understanding everything you just said about the original intervention, how much does it disturb you that we now have a video that has a guy saying, "That's a hell of a choke hold, you're placing on him, you're going to kill the guy," and the chokehold continued.

Evelyn: Yes, that is disturbing. In that case, a choke hold is meant to subdue. If the man was unconscious, then you should release the choke hold. You could have put him in a different posture where he could have continued to breathe and he would've been alive at the end. That also speaks to this marine was trained to do things above and beyond. He was trained for battle, not for dealing with someone on a subway car. Yes, in that instance, that went a little too far. He should have released, he could have been put in a different position.

Brian Lehrer: Evelyn, we really appreciate your call. Thank you very, very much. Errol, we have it as we're starting to run out of time from a whole host of callers with very different perceptions of what happened there.

Errol Louis: Yes. Look, I think Evelyn's point is close to how probably most of us feel. It's certainly close to how I feel, which is, "Oh, my God, what are we going to do?" Here we have this situation. Let's assume people are just trying to do the best they can, in a difficult situation and feeling angry that they're even in that situation. We do need broad public education, about the right way to deal with this. If the MTA and all these other agencies are not going to make it so that this is a rare occurrence or a more rare occurrence, then they at a minimum could maybe arm us with some information, and tell people, give people some sense of the range of options that they have.

In situations that have come closest to this that I've personally witnessed being on the subway, what people mostly try and do is get the disorderly person off the train at the next stop. They wait till the door is open, and then they say, "Hey buddy, I think this is your stop." In some cases, they maybe even get a little handsy and sort of shove the person through the door.

The idea being, let's just get this behind us and move on with our day. I think there needs to be some sense of that. It's when people start to think that they have to be an avenging angel and they think they're defending society or something like that, I think this is where you'll get some really distorted uses of force that can go well beyond what the situation or the law really requires or allows.

Brian Lehrer: Errol Louis, host of The New York Politics show, Inside City Hall on Spectrum News NY1, weeknights at 7:00, and a New York Magazine columnist. Errol does have a new piece in the magazine about the Daniel Penny, Jordan Neely case, the legal and the housing, and other issues it raises. Errol, thanks so much for sharing your thoughts with us this morning. You're starting a long day, I know. Thanks a lot.

Errol Louis: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.