A Labor Showdown in Alabama

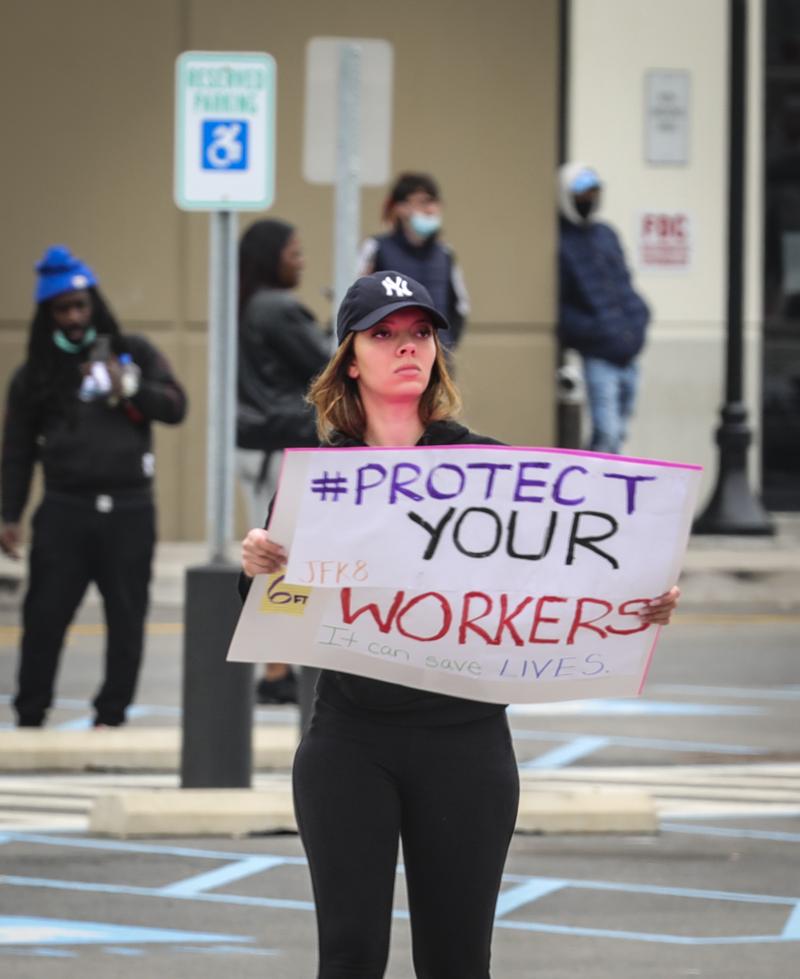

( Bebeto Matthews / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. The New York Times reports that during the pandemic, Amazon has added 23 new warehouses in New York City, New Jersey, and on Long Island combined. 23. 9 in the city, the other 14 in Jersey or on the Island, so it's very relevant to life around here that some Amazon workers in Alabama are trying to do something none have succeeded in doing before, forming a union. Joining me now to look at the organizing effort and the implications for us all is Lynn Rhinehart, senior fellow at the Economic Policy Institute think tank and former general counsel for the AFL-CIO. Lynn, thanks so much for some time today. Welcome to WNYC.

Lynn Rhinehart: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Brian: Can you describe this Amazon warehouse in Bessemer, Alabama, and who works there?

Lynn: Sure. Well, the Bessemer warehouse, as I understand it is similar to Amazon warehouses all across the country. A huge, huge facility, employing thousands of workers who fill packages with Amazon orders that consumers across America are placing for products. It's hard work. It's difficult work. It's long work that's being performed by thousands and thousands of workers at these facilities.

In Bessemer, workers there have decided that they would like to form a union to be able to have a stronger voice to negotiate with Amazon over things like safety, pay benefits, work breaks, and those sorts of things. They believe that they're stronger together in negotiating with Amazon and so they would like to have a union.

Brian: Talk about a 21st-century company town, Bessemer is a town of about 27,000 residents, per the 2010 census according to what I read, just 27,000 people, and the Amazon warehouse employs 5,800. This is as I say, a 21st-century company town. Does that have anything to do, that concentration of local residents working for the Amazon warehouse, anything to do with why this unionization effort is breaking there, as opposed to any of the other who knows how many Amazon warehouses there are around the country?

Lynn: I think it's hard to say whether or not the concentration is the driving factor. Certainly, I've read that there are a lot of workers at the Amazon facility who have had experience working in unionized facilities before and it's one of the reasons why they want to have a union at Amazon, but I think it's hard to say whether or not it's because it's in a small town or not. Certainly the fact that it is in a small town, if the workers are successful in forming their union and 6,800 of those Bessemer residents have a union, that's going to be good for those workers, and it's going to be good for the economy of Bessemer.

Because one of the things that we see when workers choose to unionize is that they tend to negotiate higher pay and better benefits with their employers, and they set a higher floor that benefits other workers in the community. It's something people don't often think about, that unions are actually good for all workers, both the unionized workers and non-union workers because unions help raise the floor for everybody.

Brian: Listeners, any Amazon workers out there right now, anybody who works or has worked at an Amazon warehouse in particular. We would love to hear from you about working conditions and pay and why you think unionization is a good or a bad idea. 646-435-7280. From anybody who has a question for Lynn Rhinehart, former general counsel for the AFL-CIO, now at the Economic Policy Institute, and a columnist for the nation. 646-435-7280.

President Biden weighed in on this on Sunday when he posted a video on his Twitter page strongly denouncing anti-unionization efforts. Let's take a listen to 48 seconds of what he had to say.

President Biden: Today and over the next few days and weeks, workers in Alabama and all across America are voting on whether to organize a union in their workplace. This is vitally important, a vitally important choice as America grapples with the deadly pandemic, the economic crisis and the reckoning on race, when it reveals the deep disparities that still exist in our country, and there should be no intimidation, no coercion, no threats, no anti-union propaganda. No supervisor, no supervisors should confront employees about their union preferences. Every worker should have a free and fair choice to join a union. The law guarantees that choice and it's your right.

Brian: President Biden on the Amazon warehouse in Alabama unionization effort on Sunday. Lynn, that was an interesting clip in a few ways. One way is that the President seemed to be walking a line there. He wasn't explicitly expressing support for joining the union or forming the union, he was supporting people's right to make that choice. Why do you think he was walking that particular line?

Lynn: Well, I think he made it pretty clear in that clip that he thinks that unions are a good thing. He also made it clear that whether or not workers want to join a union should be their choice. It's worker's choice, it's not really up to the employer. It shouldn't be up to the employer whether or not workers form or join a union.

I actually thought it was an incredibly strong statement in support of workers rights to organize and put the focus right where it should be, which is the fact that this ought to be worker's choice and employers should not be interfering in worker's choice, which is not at all what we're seeing at Amazon in Bessemer, Alabama. When workers came forward and said they wanted to form a union, what Amazon could have done, and in my view should have done, is to say, "Okay, you want a union, let's have a vote, let's just vote."

Instead, what did they do? They tried to stall the process, they tried to delay the vote, they tried to prevent workers from having a mail ballot election, because they knew if the election was at the workplace, they could keep an eye on workers and try to subtly sway the vote. They tried to slow the whole thing down while they campaigned against the union, and they've been forcing workers to attend anti-union meetings where they sit and campaign against the union and tell workers all the reasons why Amazon thinks it's a bad idea.

Meanwhile, the union can't come on the property. The union can't come on the property and talk to workers about the benefits of forming a union. They have to be outside standing at traffic lights, which Amazon got the county to change so that the cars wouldn't be at the traffic lights this long. It's a very one-sided campaign that Amazon is running to try to fight its worker's choice about whether to form a union. That's where I just think President Biden hit the nail right on the head, that this is messed up, this ought to be up to the workers.

If the workers want to form a union, great, they should be able to do so. If they choose not to, that's also their choice. It's about worker's choice. The fact that he called out employer interference and worker's choice, I thought was just really terrific. I've never heard a president of the United States put it quite like that. I just thought it was a very inspiring endorsement of worker's rights to organize.

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Dan, in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, Dan.

Dan: Hey, Dan, from Manhattan, first time, long time. I do have a question actually. What can we as consumers do to support this unionization effort? Amazon is so tangled up in everything we do. It's a hard thing to boycott. It's a hard thing for them to feel. Lynn, what do you suggest the average Joe do to show their support and to help this unionization effort?

Lynn: That's a great question. I can think of two things off the top of my head. One is to contact Amazon and say that you think that they ought to be staying out of this, let the workers choose. It's not Amazon's choice, it's the worker's choice, and that you as a consumer are asking them to respect their worker's choice on forming a union. The second thing would be to say the same thing publicly to your local newspaper, to call-in shows like this, and to express the view that this is really up to the workers. Amazon should not be interfering with worker's choice, that workers should be given a free chance to organize.

Brian: [unintelligible 00:09:59] in Copag, you're on WNYC. Hi, [unintelligible 00:10:02]

Caller: Hey, how are you? Thank you for taking my call. It's almost a miracle. [chuckles] Thank you.

Brian: It's not a miracle. You have a decent chance of getting on the air when you call in, but I'm glad you're on, go ahead.

Caller: I guess the screener asked me what my experience was, and I said that I was lonely because I was an older woman.

Brian: You worked at a warehouse, an Amazon warehouse, is that right?

Caller: Yes. In Bethpage, New York.

Brian: Thank you.

Caller: Because I was older, I was ignored, but I had to work really hard to prove that even as an elderly woman, I could do the job, which I did. Like, you're just working, working, working, there's no camaraderie, you just work. When you're in the workplace, it should in some way, or it could, or we hope that in some way it becomes like an outside family, and that didn't happen for me. So it really depressed me and put me in a very sad state.

Brian: There was something about the way the company organized the workplace or the workday that prevented that camaraderie from forming?

Caller: Absolutely. What it did was, it put you in a position where you're under the time clock. Even when you punched in, if you took a break, you had to stand near the punch clock because if you were minutes late, it went on a record where you could be- after you got three strikes if you were a minute late for punching in, you could get fired. There was this group of people just hovering around the time clock because you only had like a minute to punch in. It was very constructed in a way that you could be let go.

Brian: [unintelligible 00:12:05] thank you for sharing your experience. It's very illuminating. Shaheed in Bed-Stuy, you're on WNYC. Thanks a lot for calling Shaheed.

Shaheed: Thanks a lot for taking my call. The reason why I'm calling is because I support people fighting for unionizing themselves as workers. I have a serious contradiction that the people of Bessemer were selected because basically, there were Black people in an isolated, small arena, and that Amazon believed that there would be little to no resistance there. Because if you can remember, they were trying to get stationed here in New York, but then they got kicked out because of the resistance, but now they're in Bessemer, they are being resisted by a national organizing campaign.

I was participating in a rally in front of the law office of Morgan Lewis in downtown Manhattan, there on Park Avenue, because they are a union-busting law firm and they have concerns all over the country that get their pay organizing people to resist unions. Company hire them to do their best work, to bust up unions and to deny workers rights.

Also, one other thing. Jeff Bezos, this guy, he gets $35 million an hour and has a problem with poor people demanding a $15 an hour pay and some worker's right. This is outrageous, but I guess this is key to the capitalist exploitation of working people. It doesn't matter what color you are, but in this particular, Bessemer was chosen because it's a Black town and that Amazon believed that Black people aren't organized, but they are organized. They resisted slavery in one, and they resisted Jim Crow and we won that too, and we will defeat Amazon in Bessemer. I tell the people there, organize, organize, organize, and I salute you all and all those who support.

Brian: Shaheed, thank you so much for your call. We really appreciate it. Lynn, of course there's a difference between what Amazon wanted to open here, which was a headquarters that was going to employ a lot of well-paid tech workers, and the facility in Alabama, which is a warehouse. But to Shaheed's larger point of how race becomes an issue in this, it is a majority-Black workforce in that small town in Alabama for Amazon. Where do you think race comes into it?

Lynn: Well, we've seen over time that Black workers are actually very strong supporters of unionization. In public opinion research, Black workers express more positive sentiments about unionization than workers all overall. I think it's not surprising that a group of largely Black workers at an Amazon warehouse in Alabama wants to form a union, because we've seen that Black workers have long been strong supporters of unionization, and with good reason. Statistics show that Black workers actually enjoy a good pay premium if they unionize. All workers enjoy pay premium if they unionize, and definitely Black workers as well.

Unions have been shown to shrink the pay gap between Black workers and white workers, between women workers and men workers. There are many good reasons why workers would want to form unions. In addition to the fact that if you have a union contract, it just helps bring more fairness to the job and take out some of the arbitrary and often discriminatory treatment that workers can experience.

If you've got a collective bargaining agreement in place, there are rules there that the employer has to follow, and so you have a more fair process. I think that those are some of the reasons why working people decided they'd like to have a union and a collective bargaining agreement protecting them on the job.

Brian: Bloomberg News recently reported that some of the warehouse workers see Amazon as investing in the community, that a job at the warehouse already earns workers more than the minimum wage in Bessemer, a place where, to quote Bloomberg News, "A fixer-upper house costs less than a new car. It beats working the cash register at the local Dollar Tree." If the wage and health benefits of Amazon are relatively good for the area, if you accept that premise, I guess the Bloomberg analysis is that this is not a slam dunk for the workers who would have to vote on the union. It's like why rock the boat? So they say it's a close call as to whether this unionization vote will succeed because of local conditions. I wonder how you see that?

Lynn: I think that there are other issues that workers may well want to be bargaining with Amazon over, like safety, like breaks, like work time, those sorts of things that address quality of work issues that are really important to many working people, and I'm assuming important to people who work in hard jobs like warehouse jobs. It's not just about the pay and just because it's a good job doesn't mean it doesn't need to be a union job, because having a union means you can negotiate over all sorts of things that help make working life better.

The only thing is, in terms of Bloomberg saying it's going to be a close call, let's keep in mind that this is a vote that's happening in a context where Amazon has dumped millions of dollars into fighting this organizing drive. It's not like it's a neutral ground on which this vote is taking place. If it was, I'm guessing it wouldn't be a close call, but under our law as it currently exists, employers are given way too much room to influence worker's choice, interfere with worker's choice, hold these kinds of captive audience meetings where they campaign against the union, and hire these outside third party union busters that the caller was referencing, to help build the campaign and run the campaign against unionization. It's hard.

Our law currently makes it just too hard for workers who want to form a union, and that's why I'm glad that next week the House of Representatives is going to be taking up legislation to try to restore worker's rights to organize and make it much more possible for workers who want to come together and form a union to do so, without the kind of employer interference that we're seeing in the Amazon campaign.

Brian: We just have a minute left in the segment, then we have our weekly Ask the Mayor call-in coming up with Mayor Bill de Blasio, but let me sneak in one more call real quick. Camille in Manhattan, a former Amazon employee. Camille, my apologies in advance, I'm going to have to keep you to a soundbite, about 30 seconds, but thank you for calling.

Camille: Hi. I have an MFA, I worked there, it was a throwaway job, and I found that they have a predilection for a certain type of person that they like to expedite into higher positions. I am a light-skinned black female, and I just felt like there were all these people that really wanted to move up that I felt like they just didn't see them as material that they can shape and hone to move up.

They were maybe working-class people, but they looked right past the people that have the ambition and the drive and settled on me and I didn't want to be there. It was a throwaway job for me. I found that when I was there, that's what I found. The people that really wanted to move up didn't look like, I think, or fit into the model of person that they thought should move into management.

Brian: Interesting. Camille, thank you for that. Lynn, just tell us real quick, when does this come to a head? When's the vote?

Lynn: The vote is happening now. It's a mail ballot vote and ballots are due on March 29th. We should know shortly after that whether or not workers in Bessemer get their union.

Brian: Lynn Rhinehart, former general counsel for the AFL-CIO, now senior fellow at the Economic Policy Institute and a columnist for the nation. Thank you so much.

Lynn: Thank you.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.