January 6th and Presidential Accountability

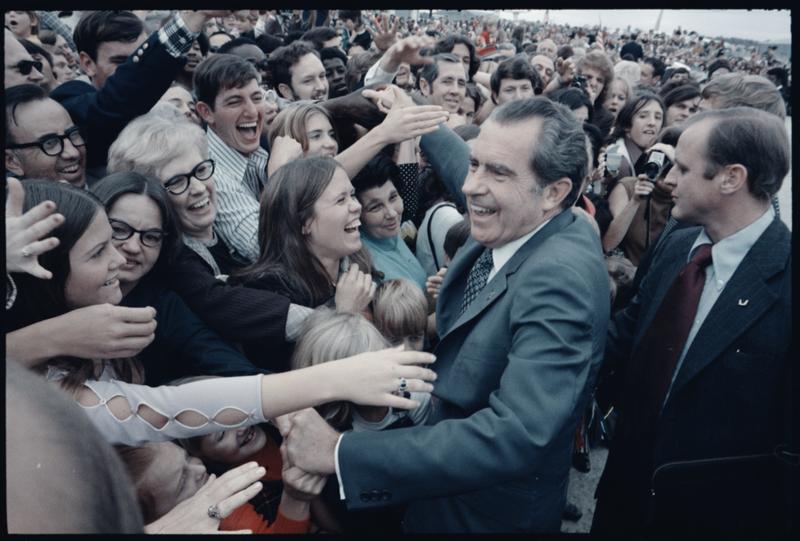

( Richard Nixon Presidential Library / Courtesy of the White House Photographic Office Collection, Richard Nixon Presidential Library )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, again, everyone. We all know that the House Select Committee to investigate the January 6th attack on the Capitol released its final report last week, but that's hardly the end of the story. Historian Julian Zelizer says the lessons of Watergate tell us now the real work begins. In a New York Times opinion piece, maybe you saw it, he writes, as with the Watergate roadmap, the January 6th report doesn't put an end to the crisis of American democracy. He joins us now to assess the work that Congress and the DOJ should do heading into the new year.

We are also joined by Jill Wine-Banks, the US Department of Justice's Assistant Watergate Special Prosecutor during the Watergate scandal, who will offer up, I'm sure, some important historical context and help us understand how and why the former president should be held accountable for his role in the January 6th attack and compare it to Nixon. Jill Wine-Banks is also an MSNBC contributor and legal analyst, and the author of The Watergate Girl: My Fight for Truth and Justice Against a Criminal President, which came out in 2020.

Julian Zelizer is Professor of History and Public Affairs at Princeton, a CNN political analyst, NPR contributor, and author of The Presidency of Donald J. Trump: A First Historical Assessment, and of a forthcoming book called Myth America: Historians Take On the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past. Jill and Julian, welcome back to WNYC. Welcome back, both of you.

Julian Zelizer: Thanks for having us.

Jill Wine-Banks: Great to be here.

Brian Lehrer: Jill, take us back some 50 years to the aftermath of the Watergate scandal and the debate over how to hold the president and his co-conspirators accountable. Nixon, as we know, had to resign the presidency, which many people considered punishment enough, but he was never prosecuted for what many people considered crimes. What went into those deliberations?

Jill Wine-Banks: There were a variety of opinions on the staff of the Watergate Special Prosecutor. I was for indicting Richard Nixon while he was the sitting president and then raise that issue again right after he resigned. Leon Jaworski opposed that position. While we were discussing it after he resigned, when Leon was more inclined to accept that position, he got pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford, and that ended the possibility of indictment. He was named an unindicted co-conspirator in the indictment and so, in a way, he did get some accountability through the trial of his co-conspirators, but he did not get indicted.

As you said, Gerald Ford and many others thought that it needed to be ended and that's why he pardoned him. I think that was the wrong decision and we're seeing the historical result now. If he had been indicted, he would've been convicted in the same way that if he had gone to trial in the Senate, he would've been convicted. That would've ended the discussion today about can you or can you not indict a former president. Can you hold someone accountable for crimes committed while in office? The answer would've been clearly, yes.

I just want to add one other thing, which is, you mentioned the roadmap. The roadmap in the context of Watergate was a document that we prepared to give to the House Judiciary Committee, which was doing the impeachment inquiry. It was us giving them the evidence as a roadmap to impeachment versus in this case where the House Committee is giving the Department of Justice a roadmap. That's a very different circumstance.

Brian Lehrer: Julian, I saw the presidential historian Michael Beschloss on television the other day saying not prosecuting Nixon might have seemed like a good thing at the time, "our long national nightmare is over," I think was what Gerald Ford said. Resigning the presidency was considered consequence enough by many people, accountability enough, but that doesn't wear well over time because of the lack of precedent that it sets for Donald Trump who allegedly has committed much worse things than Richard Nixon even did. Do you agree with Michael Beschloss about that?

Julian Zelizer: I think there's a strong argument to be made that when President Gerald Ford decided to pardon Nixon, it was choosing at least an imagined path toward healing the nation, which isn't actually what happened, over accountability, and that when you miss the chance to impose accountability when it's viable, when the political circumstances are right, you leave things undone. I do think the Nixon case is a famous one with the president and the individual where things were not resolved.

I do believe that since that time, there's been a high cost. I'll add, he didn't heal the nation. The nation moved farther apart, Gerald Ford's own standing plummeted after he issued this pardon, so it didn't even work the way he anticipated.

Brian Lehrer: Jill, as we look at the January 6th convictions and prosecutions that are taking place, and that they're all so far of pretty low-level individuals, just those who heeded the call to come to the Capitol that day and took the step of breaking in or trying to obstruct the proceedings, things like that. When we look back at Watergate, some of the high-ranking officials of the Nixon administration did go to trial, did go to prison, even if Nixon himself didn't. We're not seeing that yet with January 6th, but that happened in Watergate, didn't it?

Jill Wine-Banks: It did happen, and it is what must happen here. As I said, I am all for indicting, assuming that there is nothing in the evidence that we don't know that would be exculpatory. Based on the evidence that is available to you and me and Julian right now, the evidence seems to be clear that there have been crimes committed and that there needs to be accountability for that. Yes, the chief of staff, the chief of domestic policy, the former Attorney General, all went to jail. The White House counsel went to jail. All of those people went to jail on the same crimes for which Richard Nixon was guilty and was a co-conspirator.

There's no question about his guilt. The evidence was very strong, very clear. In that era, we had bipartisanship, which would have allowed a conviction without fear of a civil war or some other violent outbreak as a result of it. I hope we can get back to facts mattering, which is what happened back then. We also only had basically three networks. There was no social media, there were no cable news shows, and so all the networks had the same facts. There was no disagreement about what was reality. Whereas now, you have people actually believing totally made-up information, completely false, and people aren't reading the actual documents.

If they would look at not just this report but also the underlying information, read the transcripts, the transcripts are devastating. That's one of the things that maybe is even more impressive than the actual 845-page report, is the actual transcripts and listening by reading them to the words of Republicans, of people who worked in the White House, who talk about the crimes that were being committed.

Brian Lehrer: Julian, for you as a historian, and listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking about January 6th through a Watergate lens. The prosecutor meets the historian. Jill Wine-Banks was a Watergate prosecutor, and Princeton historian, Julian Zelizer. You wrote in your op-ed in the Times, it took almost a decade to set in place a suite of laws to deal with the toxic foundation of Nixon's presidency. That's not just about who goes to jail for Watergate, that's about something structural. What happened then, and what question do you think it raises for now?

Julian Zelizer: There were two streams of issues. One was Nixon and the individual connected to the presidency. Do you have accountability? That's a large part of the January 6th report. Then there was a second question in the 1970s, how do you fix the system? How do you deal with some of the underlying factors that allowed Nixon to do what he did? What were the roots of the imperial presidency?

The '70s is a really interesting period in that you have this coalition of good government reform organizations like Common Cause, legislatures on Capitol Hill, often referred to as the Watergate babies, people who were elected in 1974 and were committed to making the system better, and investigative reporters. They pushed for legislation for years. Although it wasn't perfect, there were a lot of important bills to get through in the '70s, including campaign finance reform in 1974, reform to the intelligence system in 1978, before Nixon steps down, War Powers Resolution, budgeting reform, ethics and government reform, and much, much more.

The point was reformers understood that you can't always contain or anticipate bad behavior by elected officials. Part of the challenge is how do you strengthen the democratic system. I think that's a question right before Congress today. There was one initial success with reform that passed last week of the Electoral Count Reform Act, which tries to close some of the holes that Trump wanted to exploit. Much more needs to be done, from voting rights to additional protections of how the electoral count actually works. Unless we do that, I think we're perpetually going to be in a dangerous place.

Brian Lehrer: Jill, anything you want to add about the reforms that Watergate brought or ones we're looking for after January 6th?

Jill Wine-Banks: Let me talk first about the ones from Watergate, which definitely included campaign reforms that were essential because without so much unaccountable money, Watergate wouldn't have happened. The White House had hundreds of thousands of dollars, which back then was like millions of dollars, in safes in the White House that they could use for anything. They used it for stupid things like the Watergate break-in, which if they were making decisions based on limited resources, they would have never used it for that. That was undone by the Supreme Court in Citizens United.

The protections that we got in that legislation have been undone and Congress hasn't found a way to reform the campaign system. I would say the other big difference is that even with the Electoral Count Act Reform, which is wonderful and was very much needed, was one of the most obvious things that was needed, that can only cure what has already happened. They have stopped the gaps that were trying to be exploited by Trump and his colleagues. What happens when you have bad immoral people in office, they will think of new ways around existing laws.

I think as Julian said, you cannot always predict what the new ways around are. The only way around that is electing people of good moral character and not people who are liars. Your last segment you were talking about Santos and his lies. If he's in Congress, he can't be trusted any more than Donald Trump who has a history of lying can be trusted. We have to focus on better candidates.

That doesn't mean we don't add all the laws that we can possibly add that might stop this, but who would have ever predicted a president would try to interfere with the peaceful transfer of power? That's something that is so unlikely that no law existed to stop it. In the same way that there's no enforcement to the emoluments clause, because we never really thought a president would do what Donald Trump did. We need to fix all of those things that we now know about. Predicting what future evil may come is a little harder.

Brian Lehrer: Jill, you got a fan out there. Maybe a new fan, I can't tell for sure. Listener tweets, "Love this guest. Too legit, Nixon prosecutor." Then he asks, "What about the complicit congresspeople who voted for Trump's coup, if Trump is being charged, or the committee is suggesting that he be charged with not just inciting violence but basically staging some coup through these legal machinations that he was trying to pull, what about all the congresspeople that voted to try to implement it?"

Jill Wine-Banks: Absolutely, there is culpability for some of them. There is a problem with the speech and debate clause and holding people accountable for their vote on the floor. That could be a problem, but many of them did much more than that. Think of all the people who were texting and trying to interfere, who are contacting members of state legislatures to have them interfere, people who were helping with the planning of the fake electors, all of those people. It's not just members of Congress, although, obviously, it includes members of Congress. Beyond the members of Congress, there were many people involved.

The Department of Justice is starting to move up the chain now. You had the leaders of militia groups on trial and convicted of seditious conspiracy. There are more underway right now. The subpoenas that have been issued indicate that the Department of Justice is finally-- it's late to the game but they are finally taking action. I just want people listening to remember that the Department of Justice has a much higher standard.

When the committee reports out, it lets us know what it knows, based on whatever standards it has. In a courtroom, you have to prove beyond a reasonable doubt and with admissible evidence. Compelling as some of the testimony was, it isn't necessarily admissible evidence. Cassidy Hutchinson is hearsay. That's not admissible in a courtroom. You need to get Ornato to say what happened, not what somebody else said. He said. That's a problem.

Brian Lehrer: The secrets of this agent who Trump maybe tried to commandeer the steering wheel of the car from. Elon in Nyack wants to talk about Ford pardoning Nixon. Elon, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Elon: Oh, hello. Thank you for taking my call. This is something I've wanted to discuss for many years but never thought I could, but in terms of this discussion, I think it's important. During the time when Ford was pardoning Nixon, I was part of a woman's group. We were very close. We met quite frequently. One of the women in the group had a father who was very high up in the Ford administration.

He had told her something that he swore her to secrecy but she told us, which was that the reason that Ford pardoned Nixon was because Nixon had threatened to reveal military nuclear secrets to the Russians, to other hostile state organizations, and they were too afraid that he was a loose cannon and would actually do that.

Brian Lehrer: You mean if they prosecuted him he would do that?

Elon: Yes, that he was, in effect, blackmailing the Ford administration with revealing state secrets if anything negative happened.

Brian Lehrer: Gee, a disgraced president taking home state secrets, where have I heard that before? Julian Zelizer, as a historian, have you ever heard that theory before?

Julian Zelizer: I've heard a lot of theories on the pardon. There's other theories that were very alive at the time that this was part of a corrupt deal of how Gerald Ford even became vice president. The pardon was the payback. That was front-page accusations at the time. What I saw in the archives accords more with what Ford was saying. I'm not sure he was right in his logic, but this effort to move beyond that window, his fear that criminal prosecution would open up more wounds in the country and beyond ending and get very ugly politically, was what I saw him and his advisers talking about.

Again, there is no shortage of theories. This was part of why Ford's own reputation gets undermined. At the time, his popularity is very high before he pardons Nixon. People are excited about his presidency. They're feeling maybe he is the person who could restore some normalcy. As soon as he does that, the polls plummet, these kinds of stories surface, and people see Ford very much as connected to Watergate as opposed to an antidote to Watergate.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. We've just got a minute left. Julian, I'll give you the last word because you read in your New York Times op-ed, that though we have been talking in this conversation about lessons from Watergate, for the post-January 6th era, that the problems that the January 6th committee report highlights are different in nature from the problems of Watergate. In addition to all the similarities we've discussed, very briefly, what do you see as the biggest differences?

Julian Zelizer: The biggest difference is it's connected to presidential power, but it's also about the democratic system itself. It's looking much more closely at everything, from the way we count the votes to the power that state legislatures have over the vote count to, I still think, voting rights and money and politics as part of the whole agenda, but it's about the democracy, not just the presidency. We need to keep an eye on all the problems that had been discussed before the midterms. They're not healed, they're still very much there. That's where reform is essential.

Brian Lehrer: We thank Princeton historian Julian Zelizer, author of books, including his forthcoming Myth America: Historians Take on the Biggest Legends and Lies About Our Past, and former Watergate prosecutor, Jill Wine-Banks, author of The Watergate Girl: My Fight for Truth and Justice Against a Criminal President. She is also the co-host of the podcasts Sisters-in-Law and iGen Politics. You like how I emphasize law there? This is not your family. This is because you're a former prosecutor, sisters-in-law, so they're the podcasts. Jill and Julian, thank you so much.

Jill Wine-Banks: Thank you, Brian.

Julian Zelizer Thanks for having us.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.