A.J. Jacobs Lives Originalism

( Crown Publishing / courtesy of the publisher )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, again, everyone. Let's say you're Samuel Alito, or Clarence Thomas, or Amy Coney Barrett, your job is Supreme Court originalist as you try to apply the values of 1789 when the United States Constitution was written and ratified to every controversy that comes your way in 2024, plus the strictest interpretation of the 27 Amendments that followed. You're not always a strict constructionist, like when Colorado finds that Donald Trump is disqualified from the election there because he violated the insurrection clause of the Constitution.

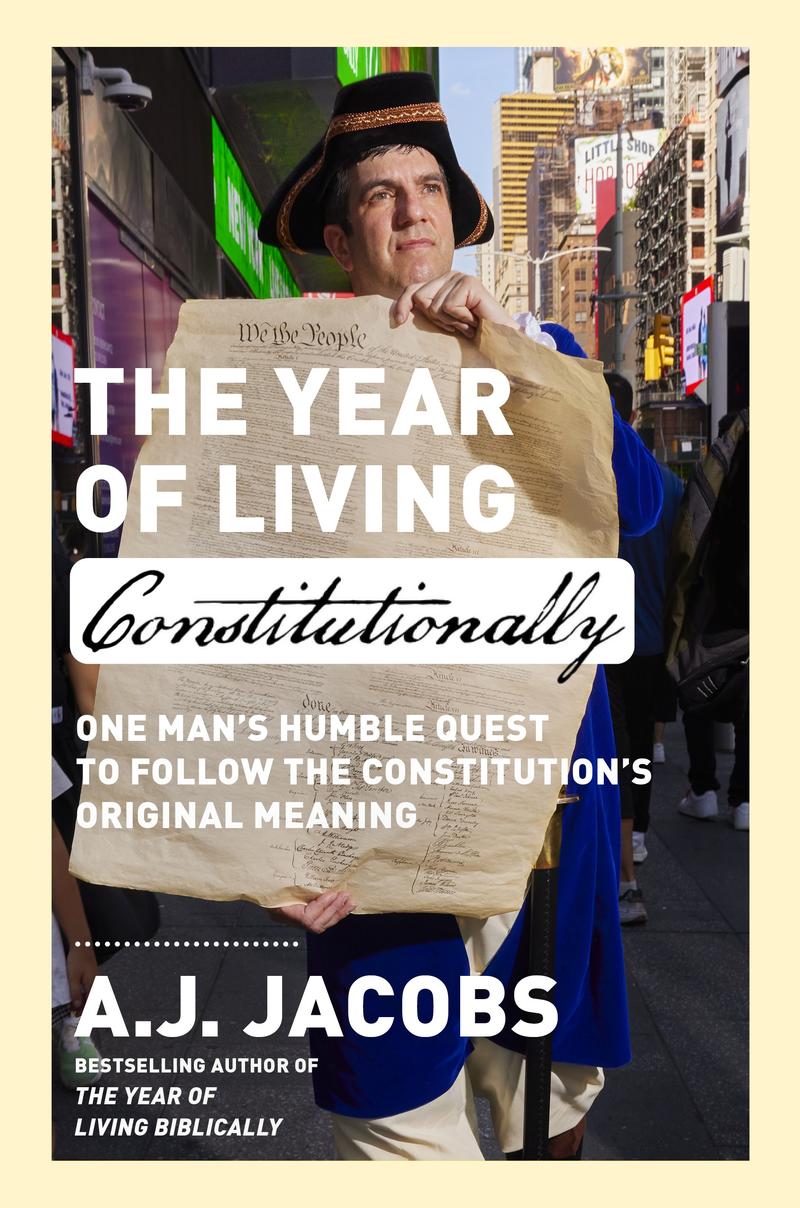

Then maybe you say, "Oh, Colorado, don't take it so literally." Usually, you're a strict constructionist, that's your job. Our friend, A.J. Jacobs, went those justices one better. He decided to live strictly according to the US Constitution in his personal life, for one full year. The result is A.J.'s latest book, The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man's Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution's Original Meaning. Now, some of you know that A.J. has done this kind of thing before. One of his previous books was The Year of Living Biblically.

Another was It's All Relative, in which he set out to build the ultimate family tree showing how every person on earth is related to one another. I think he established that he and I are 49th cousins or something, but now, it's The Year of Living Constitutionally. Let's see if we, the people, in order to form a more perfect radio show, can find out how he did it. Hi, A.J. Welcome back to WNYC.

A.J. Jacobs: Good morrow, O'Brian. It's good to be back.

Brian Lehrer: Is that what they said in 1789, good morrow?

A.J. Jacobs: It is, it is. It means good morning. I think it was appropriate.

Brian Lehrer: I've heard of it. Why did you decide to live strictly according to the Constitution?

A.J. Jacobs: You mentioned a little in your introduction, but I realized, a couple of years ago, I had never read the Constitution. I know the preamble, the we are the people part from Schoolhouse Rock!, thank you, but I never read the whole thing, and yet, every day, on the news I would see how this 230-year-old document was having a huge impact on how Americans live their lives, was still the center of urgent debate. I thought, I want to find out what does the Constitution really say, what does it really mean?

The way I like to understand the topic, as you mentioned, is to dive in, to immerse myself, so that's what I did with the bible, and my book, The Year of Living Biblically. I followed the 10 Commandments, but I also grew a huge beard. I thought, "I'm going to do the Constitution the same way. I'm going to follow the original meaning, become the original originalist," and I did. I carried a musket on the upper west side of New York, for my Second Amendment. I renounced social--

Brian Lehrer: I'm glad I didn't run into you on that day.

A.J. Jacobs: [chuckles] It wasn't loaded, so you wouldn't be in much danger. I renounced social media, and wrote pamphlets with a quill pen, and just trying to get inside the minds of the founding fathers. It was absurd, and ridiculous at times, but it was also-- I had a serious goal like the one you mentioned. How do you interpret the Constitution in 2024? How should it affect our lives? How, ultimately, can we keep democracy alive?

Brian Lehrer: To respect the framers of the Constitution, you put yourself in their shoes, and from some of the--

A.J. Jacobs: Then buckle the shoe.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. From some of the photos I've seen, you put yourself literally in their shoes. What was that re-enactment shot I saw?

A.J. Jacobs: That's right. No, I walk the walk, I talk the talk, I wore the tricorn hat, I wore the stockings. By the way, I will always be grateful now for elastic socks because I had to put little belts on my socks every day. Yes, I--

Brian Lehrer: Things we take for granted.

A.J. Jacobs: Exactly. I will never take elastic or democracy for granted. Those are two big takeaways.

Brian Lehrer: You say, to be a real originalist, you wrote this book with a quill pen. I guess that's rather than Microsoft Word or something.

A.J. Jacobs: That's right. I did a quill pen, by candlelight. I will say, we do not want to go back to the 18th century. It was in many ways a terrible time. It was sexist, and racist, and dangerous, but there are some elements that are worth reviving, I think. One is not writing with a quill but writing offline. I feel the way I thought changed. I do think that was something that the founders might have experienced. You think in a more deep and nuanced way when you're not getting pinged and dinged by the internet every three seconds.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to get into some of the serious issues that you explore even through a lot of humor, but your book is a lot longer than the Constitution. I am sitting here, holding a tiny pocket Constitution. Some of our listeners know we give away a pocket Constitution in our membership drive sometimes, and it really is a pocket Constitution. You can stick this tiny little book in a shirt pocket. It's so small, fewer words than let's say an expressive New Yorker article. Did you consider limiting your text to the original Constitution's length?

A.J. Jacobs: [chuckles] That would have been easier. I don't think we could charge the amount for my book, but it is a great point. The US Constitution is one of the shortest Constitutions. I think Monaco is the only other shorter Constitution in the world, and it has huge impact because it means there is so much that is unwritten. The invisible Constitution, and so much is about the interpretation.

Brian Lehrer: I am taken by your vision of yourself working around the upper west side with a musket to demonstrate the Second Amendment, I guess. I thought the Constitution says I have the right to bear AR-15s. Did I misread that?

A.J. Jacobs: It doesn't say-- Some people think it says that, but yes. This was one of the-- I have a large section on what does the Second Amendment mean? At the time, when it was ratified, muskets were the main weapon of choice. Muskets, I learned, are vastly different than guns now, which is part of the point of the book. I actually did fire a musket. I went out with some reenactors, and we fired muskets. It is hard, it is like, 15 steps. You've got to take out the gunpowder, take out the ramrod. It's like building an IKEA table. It is a vastly different machine and would be very hard to do a mass shooting with a musket.

This is one source of debate. On the one side, you have gun rights advocates who say, "It just says arms. That means every arm." Trying to restrict it, that's like saying the First Amendment only applies to wooden printing presses. The other side says, "No, these are two vastly different machines." It would be as if you had a law saying that wheeled vehicles are allowed on the street. At the time, wheeled vehicles were carts and bicycles. Now, we have Mack trucks. Is that the same? Should we be evolving and changing the law with this vastly different technology? My answer is, I do think, yes.

Brian Lehrer: You do think, yes?

A.J. Jacobs: That we need to evolve the Constitution.

Brian Lehrer: Oh.

A.J. Jacobs: We should not be allowing AR-15s just under the Second Amendment.

Brian Lehrer: If we just--

A.J. Jacobs: All right.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead. Sorry, you want to finish your thought there. Go ahead, I'm sorry.

A.J. Jacobs: No, it was a big theme of the book is this originalism where the most important thing is the original meaning of the words versus this idea of pluralism, or pragmatism, or living Constitutionalism, how much we need to evolve the meaning of the words because the morals have changed.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to get into that in a little more detail in just a second. Listeners, if you're just joining us, our guest is A.J. Jacobs, author now of The Year of Living Constitutionally: One Man's Humble Quest to Follow the Constitution's Original Meaning. We can take some phone calls for him. 212-433-WNYC, your questions about A.J. Jacobs' Year of Living Constitutionally. Welcome here, or maybe some of you have tried it yourselves. Strict constructionists in the audience, how did that go? 212-433-WNYC. Call or text 212-433-9692.

Again, unless we give people the wrong idea now that we've established the tone of how you often present. You do get serious about many things regarding the Constitution in this book. For example, to go back to what you were just saying, it's not just Trump and the authoritarians who say, "Terminate the Constitution." He has said that. There are a number of legal scholars on the left who say we should really scrap that old thing, and start over because as you delicately put it, it was written by wealthy racists who thought tobacco smoke enemas were cutting edge medicine. Do you analyze the most seriously flawed underpinnings that haven't been addressed by amendments?

A.J. Jacobs: Absolutely. Yes. As you say, I hope it's an entertaining book, but it also has very serious points. One of them is, what do we do with the Constitution? Do we scrap it and start a new one where people on both the far left and the far right are advocating for that? That makes me very nervous because I don't know what's going to come out of it. The other option is we are stuck with this Constitution, which has some amazing parts. It was in some senses the big bang of democracy, even though it was a very narrow democracy at the time. They wanted it to be changed. That's why they put in the fifth section where you can make amendments.

The problem is they didn't think it would be so hard to change it. They didn't anticipate this two-party system. It is almost now impossible to change the Constitution. What do we do with that because we are stuck with some very problematic anti-democratic mechanisms from the Constitution that they put in there to make it less democratic because they didn't trust the people fully like the electoral college and the electoral college has caused massive problems. I'm going to drink some of my [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Yes. That's okay. I'll jump in. Did they have alcoholic beverage of choice that you discovered in your research about Constitutional originalists who originally wrote the Constitution?

A.J. Jacobs: Absolutely. They were fans of Madeira was their main one, which is a fortified wine. One shocking thing was they were day drinkers and night drinkers. There was a lot of alcohol going on. I am impressed that they actually got stuff done with the amount that they were drinking.

Brian Lehrer: Could the Constitution or elements of it be challenged in court on the basis that the people who wrote it were drunk at the time?

A.J. Jacobs: That is a novel legal strategy. I would support it if you want to try.

Brian Lehrer: You draw attention to the tension in the little preamble to the Constitution between individual liberty and the general welfare. What jumped out at you there?

A.J. Jacobs: Well, back then, I think that they were much more aware of that balance than we are. Some of my favorite legal scholars talk about how we almost fetishize individual rights and that the founders and many other countries didn't believe that's the best way to go. You shouldn't have an absolute right to say anything you want at all times, shooting down when someone's speaking, you could say, "Oh, I have the right to shut them down." What about the other rights? The rights of the speaker, the rights of the audience, the right of the theater to make a living. That is a different way of envisioning rights that I think is a little more balanced and something we could get back to.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I'm going to read the whole preamble to the Constitution now because it is so short, and people may not have heard it in a long time or read it from the tiny little print in my tiny little pocket Constitution. "We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, established justice, ensure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America." There's the general welfare clause, which suggests something more communal, even though so much of the Bill of Rights has to do with rights for the individual.

A.J. Jacobs: Right. I think that they would've had a bill of responsibilities to balance the Bill of Rights because it was such -- but it was so assumed. It was so ingrained that you had a responsibility to your community, your country, whether that's the bucket brigade and putting out fires or being a part of the militia. I think that that is something that we could recover. When I wrote, there's a movement now to write family Constitutions. You write a Constitution for your family, and I have teenage sons. In addition to the Bill of Rights, they can sleep late on Saturday, a bill of responsibilities. I do think that that sense of civic responsibility would make our democracy stronger.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a very provocative thought from a listener on your whole exercise of living Constitutionally, living your personal life according to the strict language in the Constitution for a year, listener writes a simple one-sentence question, "Could a Black person do the same exercise because a Black person would probably have to go get themselves enslaved somewhere?"

A.J. Jacobs: Well, I do follow the amendments as well. Thankfully there's the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, but it is, I definitely wrote about race relations, which of course is a huge part of the Constitution. I found, again, there are two ways you can view this. There is, before the Civil War, you had William Lloyd Garrison, one of the famous abolitionists. He said the Constitution is a pact with the devil because it endorses or condones slavery. He literally burned the Constitution on stage in front of thousands of people. Originally, Frederick Douglass was on his side. They were allies. Somewhere in the 1850s, Frederick Douglass made a turn.

He said, "Instead of burning the Constitution, let's use it because it contains the seeds of what America should be. It contains the seeds of liberty and equality. It says it in there. What we have to do is make America live up to the promissory note." That's what he called the Constitution, a promissory note. That is what Martin Luther King used, the same language, Obama used the same language in a great speech about race. It is fascinating whether you should, -- like you said earlier, do we scrap the Constitution or do we try to make it live up to its best principles?

Brian Lehrer: Clint, in Westchester, you're on WNYC with A.J. Jacobs. Hi, Clint.

Clint: Yes. I'm almost forgetting. It's been quite a while but trying to simulate living as they did by merely wearing some shoes that are somewhat uncomfortable and carrying an unloaded musket, getting down the street, getting some weird looks. What about going to an outhouse? What about chopping firewood, picking up [unintelligible 00:17:25] and things like that?

Brian Lehrer: Yes. What about that, A.J.?

A.J. Jacobs: I did the best I could, and I did. Yes. I used an outhouse, and I did chop wood. I joined the Revolutionary War reenactors, the third regiment of New Jersey. Yes. I did not have surgery without anesthesia, although I did ask my dermatologist to take off a little mole without anesthesia, and she refused for insurance reasons. I never claim I'm actually inside the mind of the founding fathers. Even just getting a taste, I think was really revelatory. As I mentioned, there were many horrible things about the past. We don't want to go back, and this was one way of reminding me, but at the same time, there were parts of the past that we might want to revisit, like writing with a quill or writing offline, I should say, or this was my favorite part of the whole experiment, recapturing the joy and awe of election day and the fact that we have democracy.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Chapter One, what you call Article One is high -- what's the exact title? I voted like it was the 18th Century.

A.J. Jacobs: Right. In some ways, of course, we don't want to go back to that because Black and Indigenous and people and women were not allowed to vote. The privileged few who could, it was a day of celebration. I won't say it was Coachella, but there was music and there was rum punch and there were farmer's markets and election cake. I started a movement to revive election cakes.

I had people all over, including lots of New Yorkers, bake election cakes for last November, bring them to the polls. Our catchphrase was democracy is sweet. People were, it was so moving. I was moved because it's such a dark time, there's so much cynicism and nihilism, and despair. This one positive act was like a wedge in the door. I said, and this made me optimistic that we can take action and make democracy safe again. I'm doing it again in November. If any listeners want to join me in Project Election Cake, just get in touch with me through my website or whatever because it was the best part of the political seasons [unintelligible 00:20:03].

Brian Lehrer: Does this involve a certain kind of cake?

A.J. Jacobs: Well, the original election cake from the '70, '90s, it has cloves. They loved cloves, everything was cloves. Cloves and figs. Some people did the original recipe. I am not a dictator, so I said, "Whatever you want to bake is fine." People were very creative. The Georgia cakes had peaches and the Michigan cake had cherries. Apparently, cherries are big in Michigan. It was not required, but cloves I did discover that was another thing that food tasted-- There was so much cloves and spices in it, that it is not to my taste.

Brian Lehrer: If you voted a Dropbox, can you include a tiny little slice of cake for the poll workers?

A.J. Jacobs: [chuckles] Someone did bring it to a Dropbox.

Brian Lehrer: Really?

A.J. Jacobs: I don't think they put it in, but they took a picture in front of a Dropbox.

Brian Lehrer: I thought I was making that up. Carol in Wilton, Connecticut, you're on WNYC with A.J. Jacobs, author of The Year of Living Constitutionally. Hi, Carol.

Carol: Hi. I just wondered if your guest had occasion to consult Ben Franklin's, the American instructor for his recipe to treat a suppression of the courses, which was when women had missed their periods. In other words, Ben Franklin had published the recipe for an abortion.

Brian Lehrer: This was like pre-mifepristone.

Carol: My point being that-- [crosstalk] Pardon?

Brian Lehrer: Pre-mifepristone.

Carol: Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Your point being? Go ahead.

Carol: --our modern originalists are a little selective in their interpretation of what was original.

A.J. Jacobs: Right. Well, I think that is a very good point. The originalists on the court are cherry-picking what they focus on about the original meeting. I did not get into that, but it's a fascinating, I'm going to look into that. Even something like the First Amendment, the original meaning of the First Amendment, it was much more constrained. The founders, I love the freedom of speech, but I love the 20th-century version, and in the 21st century, not the 18th century. There were state laws against blasphemy, against cursing, and they would never have approved of something like Citizens United that says the First Amendment protects political donations by corporations. They would have found that completely baffling.

Brian Lehrer: Do you write about Donald Trump in this book? Article 2 of the Constitution sets out the duties of the president, and Trump had this rather broad interpretation, which the Supreme Court is considering right now. Here's Trump from when he was in office in 2019.

Donald Trump: That I have an Article 2 where I have the right to do whatever I want as president, but I don't even talk about that.

A.J. Jacobs: Oh, my goodness.

Brian Lehrer: Well, apparently, he does talk about that because we had that clip. Is that what Article 2 of the Constitution says? You read it.

A.J. Jacobs: That's just the biggest misinterpretation of the Constitution I've heard in a day. The president one of the things that which shocked the founders is how powerful the President is now, both Democrat and Republican. The Congress was supposed to be first among equals, and the President was so much more constrained. War power was split up so that the Congress declared war and the president executed it. Congress did most of the foreign trade. The fact that the president's power has increased to almost a monarch is scary to me.

I started a petition. This was my right to petition in the convention when someone brought up the idea of a single president. Many delegates said, "Are you jesting? That is bizarre. We just got rid of a king. There should be maybe 3 presidents or 12 presidents, a Council of Presidents." I thought, "This is an interesting idea." I wrote a petition and had hundreds of people sign it. I brought it to an actual Senator in Washington, who was very nice to me. I don't actually want three presidents, but I wanted to remind people that the President needs to be constrained and there are ways to do that without having RFK Jr. and Biden and Trump all working together in the Oval Office. That might not be a great idea.

Brian Lehrer: You should have been at the Supreme Court's presidential immunity hearing the other week, it might have gone better. Last question. Now you've done a year of living biblically, a year of living constitutionally, a year of living by every strict piece of health advice for yet another book. Any ideas for what's next?

A.J. Jacobs: Well, my wife is begging me to do something like a biography of Eleanor Roosevelt. It's something that won't require her to board soldiers in our apartment. I might have to bow to her wishes.

Brian Lehrer: His year of living like Eleanor Roosevelt. I can't wait. A.J. Jacobs's new book The Year of Living Constitutionally. If you want to see A.J. Jacobs in person, he has an event at the 92nd Street Y tomorrow night at eight o'clock. It's free but they want you to register on the 92Y website. He'll be in conversation there with New York's Lieutenant Governor Antonio Delgado about democracy and the Constitution. A.J., will you be wearing knickers?

A.J. Jacobs: I will be wearing my tricorn hat. I think I'm going a little combination, the jacket and tie, and the tricorn.

Brian Lehrer: A.J. Jacobs, The Year of Living Constitutionally. Thank you.

A.J. Jacobs: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.