Ireland, 25 Years After the Good Friday Agreement

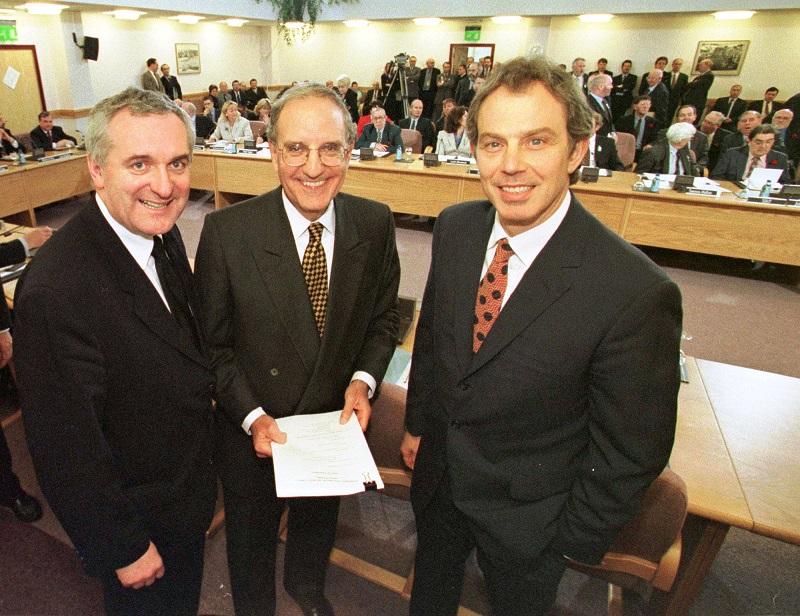

( AP Photo/Dan Chung/Pool )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone, on Good Friday 2023. Now, on Good Friday 1998, peace came to Britain and Northern Ireland. President Bill Clinton's Special Envoy brokered the deal, and the President got to be one of those who announced it.

President Bill Clinton: After a 30-year winter of sectarian violence, Northern Ireland today has the promise of a springtime of peace. The agreement that has emerged from the Northern Ireland peace talks, opens the way for the people there to build a society based on enduring peace, justice, and equality.

Brian Lehrer: President Bill Clinton on April 11, 1998. How's it working out? Can the Northern Ireland peace agreement be a model for intractable ethnic and power imbalance conflicts in other places, the Middle East, or anywhere else? We're very happy to have with us Brendan O'Leary, professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, honorary professor of political science at Queen's University Belfast, and author of many books, including one that just came out last year called Making Sense of a United Ireland.

He was an advisor to the British Labour Party during the peace negotiations, has taken part in conflict mediation elsewhere in the world since, and is a winner of what's known as the Linz Prize for contributions to the study of multinational societies, federalism, and power-sharing. Professor O'Leary, thanks for joining us on a historic anniversary. Welcome to WNYC.

Brendan O'Leary: Thank you, Brian. Good morning.

Brian Lehrer: Would you remind people, and a lot of our listeners are young enough that they don't remember what was known as the troubles? What, in basic terms, was happening in the 30 years that President Clinton referred to in that clip before 1998?

Brendan O'Leary: A generally low-intensity war in which the Irish Republican Army fought to remove the British military forces from Ireland, in which loyalist paramilitaries, largely, well, almost exclusively recruited from the local Northern Ireland Protestant Community, killed Catholic civilians to keep Northern Ireland inside the United Kingdom. There was also less combat, but still significant combat between the security forces and the IRA.

There was a largely triangular conflict, though loyalists and British forces had the same objective, maintaining the union. Over 3500 people died, and one of the major accomplishments of the agreement reached on Good Friday in 1998 was a radical reduction environment. Thousands of people are alive today, who would not be alive had that agreement not been reached.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners with connections to Northern Ireland or who just remember the era of the troubles, let's do some oral history, you're invited. 212-433-WNYC. Who wants to recall how bad it was or how you felt when the Good Friday Agreement was announced, or say anything, or ask Brendan O'Leary anything about how it's holding up? 212-433-WNYC. We'll also get into the prospect of an actually united Ireland where Northern Ireland becomes part of Ireland proper 100%. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, if you want to call in with some oral history, or a question.

Professor O'Leary, to what degree did the people of Northern Ireland feel the issue to be one of occupation by a foreign power, Britain over part of Ireland, or a sectarian conflict, Catholics and Protestants against each other as religious groups?

Brendan O'Leary: Both were obviously present. From the point of view of roughly 10% of the population, it was a war against British occupation. They would have liked to have seen a united Ireland in 1920, rather than partition. There were others who wanted a United Ireland but did not want to promote a violent method of achieving that objective. Among the Protestant community, there were those who saw the IRA as a Catholic and sectarian force. The IRA always argued that its targets were British military and peace targets that [unintelligible 00:04:39] keep to those commitments.

The level of inter-communal violence was high, but I think largely contained from the middle 1970s. The largest amount of direct sectarian killing, that is to say, the deliberate killing of people because of their religious background, was actually carried out by loyalist militia. That was partly because they didn't know who the IRA were, but more importantly, I think their strategic objective was to prevent Catholics from wanting to support the IRA by deterring them from those kinds of engagements.

It's not possible to completely separate both the ethnonational dimension of the conflict from its roots in religious difference, but I think the fundamental overriding difference was over the question of whether Northern Ireland should have come into existence in the first place. Those who favored Irish unification, Irish nationalists, were largely raged against those who supported the maintenance of the union with Great Britain.

There's no doubt that the levels of support for those two positions were strongly influenced by religious background, but I think it's fair to say that most people either voted or fought because of their national identification rather than because of their positions on theological questions. That's why when the Good Friday Agreement was made, I was actually live broadcasting on BBC World Service TV. I predicted the agreement would be called the Good Friday Agreement, and I thought it would be unfortunate because the fundamental basis of the conflict was not over religion, but rather over which state Northern Ireland should belong to.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to ask you to remember in a minute how the deal came about, and then if there's any prospect at this point, 25 years later, for still learning from it as a basis or part of a model for any other ongoing intractable conflicts. I want to take a phone call from Judith in Brooklyn who has a question about one thing that may have helped lead to the settlement. Judith, you're on WNYC. Hello. Hi, you're on the radio right now.

Judith: Hello, this is Judith. I wish I could say that everything is peaceful and everybody's happy in Ireland, but we know that there are still troubles, but I want to talk about the hunger strikes that started in 1981 in the prisons. Remember, in the prisons, the IRA prisoners were saying we're not common criminals, we are prisoners of war, and they should be treated as such, and refused to wear uniforms and draped themselves in blankets, refused to have their hair cut. They ended up, in desperation, starting a hunger strike situa-- The Bobby Sands back in 1981--

Brian Lehrer: Famous name at that time.

Judith: Yes, stopped eating. We had city-wide demonstrations here on his behalf. I participated with my infant child in a front pack for him, but it went on more and more. It was horrible. Horrible. Kids were refusing to eat because they felt they should be brave like the hunger strikers. It was so bad. [inaudible 00:08:28] to know to what extent your speaker thinks that the publicity of this helped get the British to negotiate.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much, Judith, for that bit of oral history. Professor O'Leary.

Brendan O'Leary: Thank you, Judith. The hunger strikes were a pivotal moment in the conflict. I think they played a central role in getting Sinn Féin, the political party that supported the IRA, to participate in politics. Bobby Sands, as people may recall, was elected to the Westminster Parliament while on hunger strike and died while on hunger strike. His election showed that support for the IRA did exist on a significant scale, but more importantly, that even wider support existed for resolving the conflict more broadly.

I think one of the consequences of the hunger strikes and the deep unpopularity they caused for the position of the British government, then led by Margaret Thatcher, was to set in train negotiations between the British and Irish government, which produced what was called the Anglo-Irish agreement in 1985.

That agreement created for the first time an intergovernmental conference in which the government of Ireland would be consulted by the UK Government on all aspects of public policy affecting Northern Ireland, from anti-discrimination law through to the running of the police, and then locally recruited section of the British Army, the Ulster Defence Regiment.

Ironically, you might argue that the hunger strikes ended up in facilitating both a peace process and a political process that did not immediately accomplish the goals of the hunger strikers. They would have preferred to have had an immediate United Ireland. What the hunger strikes accomplished, though this was not, I think, the direct intention, was the electoral participation of Sinn Féin, and that created an opportunity for others to negotiate with Sinn Féin in private and sometimes more publicly. Those negotiations which took place in all sorts of parallel processes eventually delivered what became the Good Friday Agreement, although that was obviously much later.

Brian Lehrer: Who else wants to share some oral history on this 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement affecting Northern Ireland? 212-433-WNYC. Mary in Middle Village, Queens does. Mary, you're on WNYC. Hi there. Thank you for calling in.

Mary: Yes. Hello, Brian. Thank you. I grew up in Northern Ireland. In the troubles was going to school. When everything started, I worked in Belfast. It was a very dangerous time.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Mary: Sorry. The British Army because where I grew up was right on the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, the British Army were billeted all around where I lived. No matter where we went, we had to go through a British Army post. When I looked out my upstairs bedroom window, they were out there in the field, billeted.

My brother going to check his cattle on the farm, he had to go through them. He had to be questioned, "Where are you going?" Coming back from checking the cattle, he had to be questioned again. Going to church, we had to go through a British Army checkpoint. My father's funeral, we had to go through a British Army checkpoint. We were surrounded with the British army.

Brian Lehrer: How do you feel today? Is the agreement working out, if you're in touch with people back there still?

Mary: Oh, yes. My family is back there, and I go back down myself. It's definitely a much more peaceful country now, but there's still things not correct yet. I think it's basically because the unionists, the majority are not-- not even majority, but some of them want to stay with the union with the United Kingdom. They don't want to go into a peace agreement to govern Northern Ireland with other parties. That's really a problem with governing the small country, which is only six counties, but part of the United Kingdom. It's on the end of Ireland, but part of the United Kingdom. That is a problem.

Brian Lehrer: Mary, thank you so much for your call. We really appreciate it. Those chilling memories, Professor, the checkpoints, and everything else. It rings true, right?

Brendan O'Leary: Absolutely. The border was deeply militarized. Those who know the region, know that there were over 300 roads across the border, 100 being described as unofficial. As part of their security strategy, the British destroyed lots of the roads and barricaded them to prevent easy access from what they feared, namely IRA forays from the Republic into Northern Ireland. The border communities, from which Mary hails, the whole experience for those decades was deeply traumatic. There were huge fortifications on the border, listening posts, and so on.

One of the fears that many people had as a consequence of the UK's vote to leave the European Union in 2016 is that they feared that a hard border might be restored. What you have to remember is the Good Friday Agreement produced a consensus that there would be full-scale demilitarization. That involves the British Army going back to barracks, and in many cases, going back to Great Britain.

It involved an agreement to remove all the fortifications on the border, to remove all the obstacles to all those roads that I mentioned. That in conjunction with joint membership of the European Union, meant that there was no need to have any customs on the land border, there was no need to have any regulatory checks, and there was no need to have any security checks because both the United Kingdom and Ireland have a common travel zone. What had been accomplished and really vigorously came into effect between 2007 and 2016, was a borderless Ireland. That removed a lot of the pain and inconvenience of partitioning.

What we've seen over the last seven years is controversies attached to the UK's departure from the European Union. Some unionists clearly wanted to see a restoration of the hard border. A majority within Northern Ireland voted to remain in the European Union, and a majority have accepted the compromise that has eventually emerged. It is a remarkable compromise. Northern Ireland remains in the European single market for goods and agriculture. The UK and European Union customs border is now applied in ports and airports between Great Britain and Northern Ireland in order to avoid the VISTA that Mary recollected to the hard securitized [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Let me ask you, Professor. In brief, how did the deal come about? How basically did they get to yes, considering the intensity of the conflict and the hard feelings based on the death and destruction on all sides?

Brendan O'Leary: Two things mattered. One is there was a political process going on since the Anglo-Irish agreement that I mentioned earlier. The elements of that agreement involved negotiations according to three strands. Negotiations looking at internal relationships within Northern Ireland, a second set of negotiations looking at North-South relationships, and a third set of negotiations looking at East-West relations between Great Britain and Ireland.

That process already existed. Then in parallel, a peace process began in which both the Irish government and the British government were in contact with Sinn Féin and in contact with, therefore the IRA, and also in contact with loyalist paramilitaries. They were, in other words, to put it in emotive language, talking to terrorists. What they eventually agreed was a method of fusing the political talks with the peace process. The parties were not required to repudiate past violence, but they were required to commit themselves to a peaceful and democratic resolution of the conflict. If that occurred, they would be allowed to participate in the formal negotiations. Broadly speaking, that's what occurred.

It was vitally important that not only was there significant British and Irish intergovernmental cooperation, but at key moments, the Americans played fundamental roles as mediators. Notably, as you mentioned at the beginning of this excerpt of your program, Senator George Mitchell, played the role of Chairman of the talks.

Brian Lehrer: Let's get at least one more oral history call in here. Joan in the Bronx, you're on WNYC. Hi, Joan. Thank you for calling in.

Joan: Oh, thanks for doing this. I lived in Belfast for 30 years during the troubles. I just wanted to point out, I think the professor left out a very fundamental thing that started the troubles was not because of the British occupation. The start of the troubles was because of the denial of civil rights for the 1/3 of the population, which were Catholic. There was discrimination in local government, housing, jobs, education.

It wasn't until the mid-1960s that you had middle-class Catholics who had benefited from the welfare state education, who started making civil rights demands just the same way that we had here in this country, Brian, with the massive marches and demonstrations by the African American population to fight for civil rights.

Brian Lehrer: Are you saying that the Northern Ireland Catholics were inspired by the US Civil Rights Movement, either in goals or tactics?

Joan: Overcome. The same tactics, the mass marches. It was only when the unionist government denied these basic rights to one man, one job, one family, one house, that we all chanted. When these were rejected and met with loyalist violence, that is when the British came in to put down the loyalist violence, and we then have the rise of the Provost to defend their areas.

Brian Lehrer: Joan, I'm going to leave it there. That was all wonderful. Thank you very much. Forgive me, this is just for time purposes. Professor, I don't think she heard my follow-up question. Did the US Civil Rights movement that was going on at the same time inspire the Northern Ireland Catholics either in goals or tactics?

Brendan O'Leary: Yes, absolutely. I would want to emphasize that I actually agree with Joan, and my description in my long historical treaties on Northern Ireland deals with these events that she describes accurately. The Civil Rights Movement sought to achieve equality for cultural Catholics inside Northern Ireland. They modeled themselves on the US Civil Rights Movement. They were peaceful and they were met with repression, but it's important to notice a key difference between the US case and Northern Ireland, namely that one reason why unionists were so bitterly opposed to granting civil rights and one reason that they preferred repression and discrimination was their fear that the cultural Catholics would eventually outnumber them and pursue a United Ireland.

The motivation for repression and denial of civil rights in Northern Ireland was, in my view, different for the motivation of the Southern racists who were particularly fearful, obviously, of the democratic consequences of allowing African Americans to become full citizens, but the status of the United States as a state was not at stake. Everybody agreed in some sense that they were Americans, though the white racists wanted to keep African Americans in a [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Similarities and differences. We've got about three, four minutes left in the segment, three or four minutes, and I want to get one question in for you, which I know you're going to want to answer, and I'm going to let Rich in Brookhaven on Long Island pose it. Rich, you're on WNYC with Professor Brendan O'Leary. Hi.

Rich: Hi. Thank you for taking my call. My question is this. I don't remember exactly where I read it, but it was in some reputable source saying that if there was a referendum on having a United Ireland in the future, say 10 years, 20 years down the road or something like that, yes, there are a percentage of Catholics who would prefer British rule, and yes, there are percentage of Protestants who would prefer, in my opinion, a united and free Ireland, but I would say the majority would vote religiously.

By projecting out current birth rates and [unintelligible 00:23:31] I believe it would be about 55% to 58% Catholic in 10 or 20 years. If there was a vote and there was a-- do you think that that would work out towards United Ireland?

Brian Lehrer: Rich, thank you very much. I just want to note for the listeners, Professor O'Leary, that the potential for a future United Ireland is certainly an interest of yours as reflected in the title of your new book Making Sense of a United Ireland. How would you answer Rich's question?

Brendan O'Leary: Well, Richard is correct that there is significant demographic change underway. The most recent census showed that cultural Catholics, those who are Catholic believers and those who come from Catholic households, outnumber cultural Protestants for the first time. What we have to remember is that Northern Ireland was deliberately created as a haven for Ulster Protestants where they would outnumber cultural Catholics by 2:1.

The demographic transformation that unionists have long feared has taken place. There will be an interval between that demographic displacement and electoral displacement. It's not just because some Catholics, as Rich said, definitely prefer the union and some Protestants, albeit a small proportion, prefer a United Ireland. It's to do with the simple fact that the electorate takes another 18 years before it reflects underlying demographic change. The Good Friday agreement quite deliberately allowed for future referendums on Irish unification.

In my view, the earliest date in which such referendums could occur with some prospect of success is about 2030. That's why I argue in my book, along with others, that massive preparation needs to be put underway to allow for managing all the complex questions that will arise from unification. I'm not saying it's definitely going to occur, but I am saying it's utterly appropriate at this moment to begin preparations, not least because of the continuing difficulties in making the Good Friday agreements institutions work.

Brian Lehrer: Last question. In these 25 years, as we acknowledge this anniversary, has the Northern Ireland Accord been used as a model for ending any other intractable conflicts? I'm thinking about how that time, the late '90s, was a time of hope for both the Northern Ireland troubles and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. One went one way, the other has gone the other way, but do you think the way peace came to Northern Ireland has helped anywhere or could help still in the Middle East?

Brendan O'Leary: It's a much tougher call in the Middle East, I believe partly, because of the number of sovereign governments involved, and because of the sheer depth of both religious and ethnic hatred. It's tougher. Nevertheless, some parts of the Northern Ireland story have been applied abroad. Number one, the idea has strongly prevailed, particularly in the United Nations, that it's always best, if you can, to get comprehensive and inclusive negotiations to get all major parties to the conflict, even those who are using violence, but you would need to get an agreement on process.

You need to get them to agree that there will be no violence in the future and that they won't be using violence while they're at the negotiating table. I think the Northern Ireland story is helpful there. It says you can't necessarily be successful if you only focus on the moderates. You have to focus on the hardliners as well as the moderates. That's lesson number one. Lesson number two [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: We've got 20 seconds left for lesson number two.

Brendan O'Leary: Some of the Northern Ireland institutions have worked quite well and we should be careful about deciding which ones are exportable and which ones are not. Police reform has worked very well.

Brian Lehrer: On the 25th anniversary of the Northern Ireland Good Friday peace accord, we thank Brendan O'Leary, professor of political science at the University of Pennsylvania, and author of Making Sense of a United Ireland. Thank you so much for joining us today.

Brendan O'Leary: You're very welcome. Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.