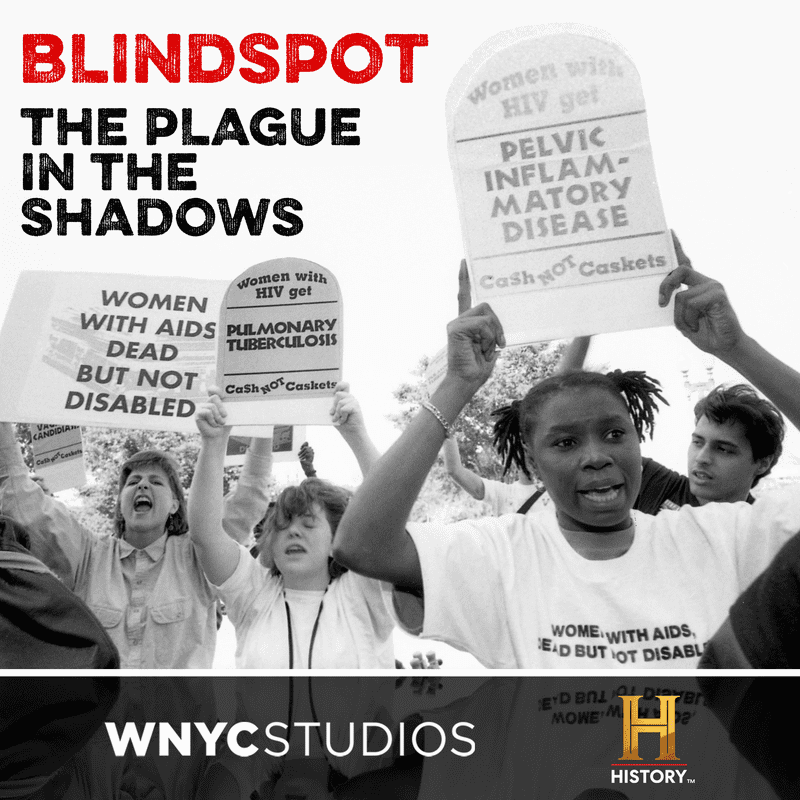

Introducing Blindspot Season 3: The Plague in the Shadows

( Photo: Donna Binder )

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. When we think of the AIDS epidemic, often the faces we picture are those of white gay men, right? Although we now know that anyone can have HIV, children, women, people of color, the virus was at first portrayed largely as a plague that affected white men who had multiple sexual partners who were also usually white men. This perception made those who got HIV through intravenous drug use, heterosexual relations, birth, or even blood transfusions, relatively invisible.

Visibility in this context is not just about media coverage or seeing yourself represented. When it comes to HIV and AIDS, being invisible rendered communities of people more susceptible to contracting the virus and unable to receive needed treatment invisible. Being invisible was effectively a death sentence. Today, the History Channel and WNYC studios have launched the first episode of the latest season of the series Blindspot. It's called The Plague in the Shadows, stories from the early days of AIDS and the people who refused to stay out of sight. Here's a preview.

Kai Wright: AIDS was not just a medical crisis, it was and it remains a social disease, one that exploits the inequities that already defined so much of American life.

Maxine Wolfe: We literally had to convince the federal government that there were women getting HIV.

Kai Wright: In the series, you will hear from extraordinary people, priests and doctors and nurses and activists, people who were told to stay out of sight, to remain in the shadows of America's dawn, and who refused.

Joyce Rivera: It was activists. We changed the world.

Speaker 1: Stigma was high. Stigma was so high that people were almost abused.

Speaker 2: They're people. They're not drug users, they're not patients, they're not hemophiliacs, they're people.

Speaker 3: Yes, we are being victimized, but we are not victims, we're models of resistance.

Speaker 4: I remember one little boy said, "If I didn't have HIV, I wouldn't have met you guys." [laughs]

Brian Lehrer: A montage of voices from the new season of Blindspot, the series called Plague in the Shadows. We're going to hear some more clips as we go as with us now are the host of this podcast, our own Kai Wright. You usually hear him on Notes from America, our live national call-in show, Sunday nights at 6:00 PM. He's here along with the lead reporter on the series, Lizzy Ratner from The Nation Magazine. Hi, Kai. Hi, Lizzy.

Lizzy Ratner: Hello.

Kai Wright: Hey, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Kai, I'm sure a lot of people listening now consider AIDS at least at a certain level of threat to life to be a threat from the past. We've already had another pandemic since then, so why are you releasing a series about AIDS from the '80s in 2024?

Kai Wright: I'd say two things are important, Brian. One is the simple fact that the AIDS epidemic is in fact, not history. Our podcast is about that history, but we have to say from the beginning that while there has been lots and lots of progress on both prevention and treatment in this epidemic, of course, in my lifetime and even in recent years, we've seen meaningful drops in new infections and meaningful drops and death rates. While all of that is true, there remain 40 million people living with HIV in the world today. We know that universal access to treatment for those 40 million people is the secret to ending this epidemic and we still don't have that.

The reason we don't have that is because of the, not medical, but social inequities that fueled the epidemic from its start around race, around gender, around poverty. That's one thing is that the epidemic is, in fact, a present-tense thing. The second thing, Brian, is that in reporting this podcast, part of what is really clear to me is we today live in such overwhelming times, whether we're talking about the climate, we're talking about democracy, we're talking about war. We are all, many of us, I certainly am, so overwhelmed and just want to pull our covers up over our head [chuckles]. It just feels like we cannot engage with these things.

The history of this epidemic, particularly early on, is the history of individuals who were facing similarly overwhelming things and taught us ways to not put our heads under the covers to say, "Well, I'm going to lead with love and through that love, I am going to figure out how to, in fact, change the world." They did so. Part of the reason of why now is there is so much to learn about how we engage the moment in which we live from the people who engage the early years of this epidemic.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a clip from the first episode of the series featuring Valerie Jimenez, an HIV/AIDS activist, she lives with HIV herself, describing the toll the virus took on her community on the Lower East Side in the 1980s.

Valerie Jimenez: People just started disappearing. One day they were there and then the next day they were gone. These 20 people that used to hang out in this building shooting up, they were all gone. Carwash, Papo, Tirso, Coco Wee, all these people, they're all gone. Where did they go?

Brian Lehrer: Lizzy, since the series is called Blindspot or this is the latest series within the overarching series Blindspot, what would you say are the blind spots that people carried then with their understanding of HIV and AIDS?

Lizzy Ratner: I think to understand that, it helps to set the scene just a little bit more. As you said, it was early to mid-1980s, Valerie was living in Alphabet City, which was this or which had been this tight-knit working-class Puerto Rican community until in the '70s and '80s the economy crashed, and in its place was this new economy, this heroin economy, and this crisis in the neighborhood of heroin. What Valerie is describing is how people who used heroin in her neighborhood or had sex with people who used heroin began to get sick with this mysterious illness, which, of course, we now know is HIV. What she goes on to say, in the moments after that clip, is that as many as 75 people died on her block alone.

Now, I've been reporting the podcast for about six months when she told me this, and that number floored me because as much as I knew about HIV and AIDS at that point, I still had this blind spot to some degree, this misunderstanding of how profound the AIDS epidemic and HIV epidemic was in the South Bronx, Harlem, parts of Brooklyn and other communities of color around the country. What was the blind spot? First, I think there was the blinding spot, which was this idea that HIV and AIDS was a gay man's disease. Now, to be really clear, that was not because there's this privilege attached to these men.

This was because of rank homophobia at that time, Ron DeSantis level homophobia or a lot worse, that just fixated on this idea that gay men were aberrant, and we're catching this deadly, awful, stigmatizing and stigmatized disease as a result. The idea that other people could get it just wasn't on the table. Of course, other people were getting it. Who were these other people? A lot of them were poor people, people of color, some of them were drug users and then as frankly now, a lot of people just didn't care. Society wasn't particularly disturbed that this large group of people was getting sick and dying, that 75 people on one block alone on the Lower East Side were disappearing.

Brian Lehrer: There were the various means of transmission which is why different groups of people were getting it disproportionately, but multiple different groups of people, not just gay men or white gay men. Here's a clip representing some of the media coverage of HIV and AIDS one might have come across in those early days of the virus.

Speaker 5: The headline read, "Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals. Outbreak occurs among men in New York and California. Eight died inside two years." Then the story began. "Doctors in New York and California have diagnosed among homosexual men 41 cases of a rare and often rapidly fatal form of cancer."

Brian Lehrer: Kai, why were people so unaware or not talking about the broader risk HIV posed to all sorts of demographics originally?

Kai Wright: It's a combination of things. It's everything Lizzy just said in terms of the fact that, A, this really was the fact that gay men were the first place that science saw it was a blinding fact for our society because of the level of homophobia that exists and because of the racism that exists that dismissed the other populations who were getting it. Also, there's just some fundamentals. There was a feedback loop, and I think we've seen this with other epidemics. It was where because the first reports were amongst gay men, then the first media reports were about gay men. Also, that's what doctors were looking for. Those are the populations in which doctors looked.

Every time there was a new public statement about this gay cancer, it led doctors who saw gay men in places like New York and Los Angeles to say, "Oh, my goodness, I've seen that," and report more cases of gay cancer. It should be clear that in the data itself, the data said, "Hey, this is a gay disease," and absolutely, it was and remains enormously. It has just been terribly devastating to those of us who identify as gay men. It fixated us on who was getting it rather than what was happening for a really long time. That fixation on who rather than what and how locked in this perception of what this epidemic was about and still gets in the way of universal access to both prevention and treatment.

Brian Lehrer: Kai Wright and Lizzy Ratner are with us as we talk about their new series, part of the Blindspot series that looks back at blind spots during the early days of the AIDS epidemic. We're going to take a break, and when we come back, we're going to play one more clip from the series, and I'm almost embarrassed to say it's a clip of somebody that the series focuses on today and who was a guest on this show in 1990. Stay with us, Brian Lehrer on WNYC.

[MUSIC - Marden Hill: Hijack]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with Kai Wright and Lizzy Ratner, respectively host and lead reporter for the new History Channel and WNYC studios podcast that's the latest season of Blindspot. It's called The Plague in the Shadows. Stories from the early days of AIDS and the people who refused to stay out of sight. We can take a few phone calls here. I wonder if anybody listening right now is someone who recalls the early days of AIDS, particularly the 1980s, and maybe has a story to tell relevant to some of the groups who were undercovered and underrepresented, and therefore, undertreated and underdiagnosed at that time.

212-433-WNYC. If anyone has an early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic story to tell relevant to the theme of the podcast, 212-433 WNYC, 212-433-9692, call or text. One of the individuals that the series focuses on is Katrina Haslip. Kai and Lizzy, I'll let you talk about her after this clip, but I can't even believe you dug this up because here's something she had to say. This is a 40-second clip about the Centers for Disease Control definition of AIDS in a roundtable interview on this show in 1990.

Katrina Haslip: I said no question when he said that the CDC definition is pathetic at best.

Brian Lehrer: Tell us why. What's the difference between real life and their definition, as you said?

Katrina Haslip: I'm personally affected by that because I feel that they have this rigid criteria of what is AIDS or their definition of what in AIDS, and none of which incorporates symptoms or illnesses of women, such as gynecological problems. Most women that develop AIDS are dying from cervical cancers and all these other hosts of illnesses that are not yet on this fine package list from CDC.

Brian Lehrer: They list Kaposi's sarcoma and PCP and things like that, but not things that are particular to women.

Katrina Haslip: Right.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, we did so many segments on AIDS in the early days of the show.

Kai Wright: Brian, you sound so young.

[laughter]

Lizzy Ratner: I was going to say you sound just the same.

Kai Wright: He's still young.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, Lizzy is right.

Lizzy Ratner: Totally.

Brian Lehrer: Who was Katrina Haslip? Why did you focus this news series partly on her? Lizzy, you want to talk about her?

Lizzy Ratner: Yes, proudly and gladly. Katrina was this incredibly charismatic, brilliant, and dedicated activist with this stunning story. She was born in Niagara Falls, and she actually wound up incarcerated at a maximum security prison in upstate New York, Bedford Hills Correction Facility, because she'd been a heroine user and a sex worker, and she pulled a knife on a John, and that got her arrested. For reasons we know, mass incarceration, racism, and all the like, she winds up in a maximum security prison. When she's there, it's the mid-1980s, and HIV is rampant in the prison. As much as, I think, 20% of women coming into the prison at that point were HIV-positive. Women were disappearing. There was all this fear.

This small group of women decided to start this, really what became one of the first, maybe the first AIDS counseling and education group for women in the country. Mind you, this happens in a prison. It's Katrina. It's this woman, Awilda González, whom we interview. It's also Judy Clarke and Kathy Boudin, the activists who are part of the Weather Underground and then did really important stuff in prison. When she gets out of prison, which she does, Katrina does in about 1990, she decides that she's going to take all the knowledge and energy that she got in prison around advocating around HIV.

By this point, I should say, she knew that she was HIV-positive. She decided that she was going to take her voice that had grown so strong in prison out to the wider world and that she was going to speak up on behalf of people who are incarcerated with HIV, women with HIV, in particular women of color with HIV. She chose to do this by joining a fight that was organized in part by Act Up, the Women's Committee of Act Up, I need to specify, to change the definition of AIDS. Now, this gets a little bit wonky, so I'll try to make it quick.

Basically, to understand this fight, you need to understand that there's HIV, which is the virus that causes AIDS, and then there's AIDS, which is the late stage of the virus when your immune system collapses and you get all these really intense opportunistic infections. The problem was that the definition that the Centers for Disease Control came up with for what AIDS was, for what all those AIDS-defining opportunistic infections were, it left out these crucial illnesses that just happened to be experienced by women, people with female anatomy or who were born female at birth.

Gynecological problems, as Katrina mentions, like yeast infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, recurrent vaginitis, cervical cancer, and also some particular types of tuberculosis and pneumonia that a lot of drug users were getting. This meant a few things. It meant, first of all, that there were a lot of people who were getting AIDS, but didn't know it because their symptoms weren't listed as AIDS. They were just getting all these infections, and they didn't know what was going on. Beyond that, an AIDS diagnosis, basically back in the day, and still now, will trigger a number of really crucial government benefits, like disability benefits, housing benefits, sometimes Medicaid.

If you could not get an AIDS diagnosis, even if you had an HIV diagnosis, it meant that you were not eligible for things like disability, housing vouchers, Medicaid. You were literally-- There were people who were dying that were becoming homeless because they couldn't work because they were so sick and couldn't get benefits. They were dying. They were being denied benefits at the very moment they were dying. This was an absolutely crucial defining fight to change the definition of AIDS to be inclusive, basically.

Brian Lehrer: I want to get at least one caller with a memory in here, and we'll definitely tell people how they can listen to the whole series. Episode 1 just launched today. Dana in Queens with a memory. Dana, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Dana: I was a therapist for the first cohort of children who were orphaned by AIDS. In my second internship year at Postgraduate Center, I did encounter a few who were memorable to me, and finding ways of helping them cope with the reality of what happened without shame and be able to help them consecrate their parents and cherish them, although the diagnosis was very shameful for them.

Brian Lehrer: As a social worker, did you run into some of the obstacles for those folks who you were working with who you just described and who Lizzy was talking about?

Dana: A paucity of programs and understanding anything that would have been socially acceptable would have made them feel that they belong to the humanity of their cohort, of their age group, it wasn't there. It was so terribly unique, and I guess, internalized as shameful, that it was very good that they came to some therapy at the time. It was family work and also community work. The school and the other access, the sources they had access to, all of those would bolster their feeling of being parented. Sports, for example. All that needed to be encouraged and given to them. The loss was irrevocable.

Brian Lehrer: Dana, thank you so much for sharing that memory. One more. Mary, in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Mary.

Mary: Hello Brian. I was a medical intern at Bellevue in 1986 and had been a medical student from '84 to '86. Most of the patients that I treated at Bellevue at that time were not gay men, though I did treat gay men. My first patient as an intern was a young woman from the Lower East Side, an IV drug abuser who was desperately ill and subsequently died. Another patient that I remember really well was from Rikers, who's on the prison service that they have at Bellevue, and he had a strange something growing in his head. I remember the neurosurgeons didn't want to operate on him because he had AIDS.

We treated him for what we thought he had, it turned out to be completely wrong, and he had something totally different, and he died subsequently. It was horrible. I spent my time fighting with Rikers to get the man to be unchained from his bed and to be released home because he was clearly going to die. We were really dealing with everyone that had AIDS in those days, at Bellevue, at least.

Brian Lehrer: Mary, thank you very much. Kai, as we start to run out of time, what were you thinking listening to either of those callers with their memories?

Kai Wright: It takes me back to the first thing we talked about in this conversation about why now are we bringing this up. Both of those stories are people who looked around in the immediate surroundings of themselves and said, "Somebody has to do something. Somebody has to engage," and chose to do so. The stories in this history and in this podcast, they include incredible things, like Katrina Haslip changing things at the structural level, making change that can affect millions of people in one swoop, but they also, and I think equally important, include people like those two callers who said, "Right here, in my community, in my family, in my church, in my job, somebody has to step up, and I'm going to step up in this way." I think those are the lessons that I am trying to hold in the times we live in right now.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to throw in one text message that came in because it's so chilling and moving. It says, "I began my career as a pediatrician at the beginning of the AIDS epidemic working in the South Bronx. We were seeing many babies with symptoms that were similar to the "plague that didn't yet have a name". We knew it was the same disease, but it took a very long time for the medical community to acknowledge that children could get it, too. There was no treatment. I saw too many babies die." The series from the History Channel and WNYC Studios is called The Plague in the Shadows. It's the latest season of Blindspot. Kai, you just want to tell people how they can access it?

Kai Wright: Wherever you get your podcasts right now. Check us out on any of your platforms. Stay tuned, we'll be doing a special about it on Notes from America in a few weeks.

Brian Lehrer: Kai Wright, host and managing editor of Notes from America with Kai Wright, our live national call-in show. If you like this show, you're going to like that show, Sunday nights at six o'clock, here on the station. Lizzy Ratner, deputy editor of the Nation Magazine, and the lead reporter on this series. Thank you both so much.

Lizzy Ratner: Thank you.

Kai Wright: Thanks, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.