Reimagining America's Monuments

( Steven Senne / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Today as you know is a national holiday, so schools and many workplaces are closed, having nothing to do with COVID for a change, but here's the question, what holiday is it? For the company that runs my apartment building, the offices are closed for what they call Indigenous Peoples' Day. Same with many people having the day off at WNYC, but at 12:30 coming to a computer near you, New York City will hold its virtual Columbus Day Parade with its Italian American Governor, Andrew Cuomo, as the Grand Marshal and special honoree, Dr. Anthony Fauci. For now, at least, it's both. If you don't yet know, Indigenous Peoples' Day it's a holiday that recognizes the ongoing impact of colonialism and celebrates the many different cultures of Indigenous peoples who were here before Columbus arrived and started a process that became a genocide. By now you're probably familiar with the debate. Little history, Columbus Day has been a federal holiday since the turn of the 20th century, but a growing chorus of voices ask that their local government change Columbus Day to honor those who were living in America before 1492. The idea was first proposed during the 1977 UN Conference and in 1989 South Dakota, with its large Native American population became the first state to ditch Columbus Day for Indigenous Peoples' Day. Now more than 100 cities, towns, and counties commemorate Indigenous Peoples' Day officially and 14 states have also made the switch. New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut states in our immediate listening area, still have Columbus Day on their official state calendars with the exception of a few counties, and that's because for the many Italian Americans in the region, Columbus Day is an important celebration, not just of Christopher Columbus, but of Italian American history, cultural pride, and a symbol of overcoming adversity and discrimination against them. When Columbus Day was created, Italian immigrants were facing racism and the hope was that by honoring Columbus, an Italian, as an American hero, that that would be a way for Italian immigrants to be more accepted into the mainstream. Many have said, calling into the show, that getting rid of Columbus Day would be like erasing that history. Others say, "Can't we love and celebrate Italian American culture without building around that guy? Maybe we should make this Indigenous Peoples' Day and make a separate national holiday out of Anthony Fauci's birthday," to take one random example. Whose history should we celebrate and whose history gets erased on the second Monday in October? This year, the day happens to come at the end of a summer filled with these questions about our national identity as you know, who gets to be honored by a memorial, a holiday, or in many cases, a statue? How do public symbols of veneration shape our national story, and for that matter, equal rights and equal justice today? Here with me now is someone who is working to address those questions. The Mellon Foundation, the largest humanities philanthropy in the United States, has pledged to spend $250 million over five years to help re-imagine the country's approach to monuments and memorials in an effort to better reflect the nation's diversity and highlight buried or marginalized stories. Elizabeth Alexander is the president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. She's also a poet, educator, and memoirist and scholar and she joins us now. Elizabeth, such an honor to have you again. Welcome back to WNYC.

Elizabeth Alexander: Good morning. It is wonderful to be back so soon. Thank you.

Brian: Which holiday are you in the Mellon Foundation honoring today?

Elizabeth: [laughs] Let's guess. Here's the thing, Indigenous Peoples' Day is the answer. I wonder if that will stay the name of this day forever, but I think that the reason that we don't use Columbus Day is that as you learn this history-- When I was growing up, I was taught only that Columbus discovered America. That was I think the language that most of us had. That's immediately interrupted once you take in the fact that there were people on the land that he discovered. There were people who were all but exterminated on the land that he discovered. The more we know of history, we have to listen to what it reveals, and that means that we assess not only our hierarchies but also our sense that you can understand more than one story at the same time and you have to do something with that knowledge. You can't pretend that you don't know that anymore when you're going about the business of veneration.

Brian: Some states and counties have decided, as I mentioned as you know, to celebrate both Indigenous Peoples' Day and Columbus Day today. Is that in your opinion, before we get to your statues and memorials project, a mindful solution, or do you think one needs to replace the other or that maybe Indigenous Peoples' Day should simply be moved to a separate day and separate these conversations?

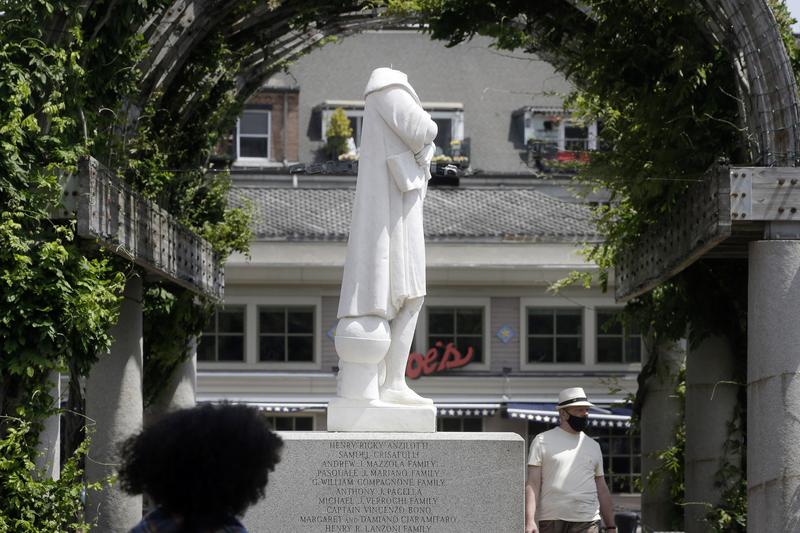

Elizabeth: The thing that I don't love about Indigenous Peoples' Day, frankly, is that it is far too broad. That's the next issue is once we start to recognize more complex histories, which Indigenous people are we talking about? Which aspect of their history? Columbus was one person, we're talking about millions of Indigenous people. I think that there's a lot of refining work that has to happen. I think that also in New Haven, Connecticut, for example, a place I know well, I've been really interested to see that there are people there, as you know it's got an Italian American community that's been there for a long time. They are having a controversy around a Christopher Columbus statue that has stood in Wooster Square in the heart of the Italian American community. The question they're asking is, who amongst Italian Americans do we want to represent the greatness of our history? I, myself, am very interested in the Watts Towers in Los Angeles, Simon Rodia Watt, an Italian immigrant to this country who over the course of decades built this astonishing, beautiful, vernacular tower to the sky in the middle of that community to say thank you to America for welcoming us. I think that once you start to really go more deeply into the richess of the stories and the [unintelligible 00:07:36] in history, within an ethnicity within a group of people, that's the hard work but the interesting and exciting work that helps us commemorate better.

Brian: Yes, I'm thinking a little bit when we talk about possibly having multiple holidays of the fight over MLK Day in Virginia in the 1980s, the state celebrated Lee-Jackson-King Day, a combination of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, and Martin Luther King Jr. That was truly weird and then in 2000, the state legislature made them two distinct holidays on two separate days so there's that strange history model.

Elizabeth: Yes, or I just learned a couple of days ago in the state of Alabama, they celebrate King-Robert E. Lee Day. This makes no sense-

Brian: No sense.

Elizabeth: -but what it tells you is that a lot of people don't want to give up and I'll put this in quotation marks, "Their holidays, their statues, their heroes." What I'm suggesting is that we all learn our history, wider, deeper, better, in its complicatedness and in its possibility, and that what we understand is that if I'm Italian American, and I want my statue, that has to be of a figure who can speak and be inspiring to anyone who might come across that person. Within every single ethnicity, there are those people who can inspire all of us.

Brian: Of course, it's a separate conversation that we won't have now that in Virginia and Alabama to use the two examples that we just used, that they continue to celebrate their Confederate traitorous leaders at all, but that's a different show. Listeners--

Elizabeth: Yes, although part of this. [chuckles]

Brian: Go ahead. Go ahead.

Elizabeth: I think that when you look at the-- and this is part of with our Monuments Project we're starting with a nationwide audit that will be conducted by an amazing group out of Philadelphia called the Monuments Lab that will do the research that we need, the aggregation of research and new research to tell us very definitively who is represented where and to what extent, so that we can think about, in very, very sharp terms, the tremendous disproportion of Confederate heroes who are army bases, schools, markers, statues, et cetera, and understand more clearly that those markers and statues were largely put up long after the Civil War was lost, and put up to instantiate an ideology of white supremacy. I think that what that brings us to very sharply is, how do we feel about history that teaches that some people are superior and other people are subhuman and continues to perpetuate that quite formed ideology?

Brian: My guest, listeners, if you're just joining us, is Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Also a poet, educator, memoirist, and scholar. The Mellon Foundation has just pledged to spend $250 million over five years to help reimagine the country's approach to monuments and memorials. Columbus Day, Indigenous Peoples' Day is a pretty good day to highlight that effort. Listeners, how are you honoring Indigenous Peoples' Day or Columbus Day? Call in and tell us about it. What do you think should be done with the second Monday in October? 646-435-7280. Literally, how? Listeners, if you are celebrating Indigenous Peoples' Day today, tell us how for the benefit of some listeners for whom this is still a new concept. How are you recognizing Indigenous Peoples' Day? For anyone else who wants to say how you're recognizing Columbus Day, and what Columbus has to do with it for you as opposed to some other notion of your Italian heritage if you're Italian. 646-435-7280. 646-435-7280 or you can tweet @BrianLehrer. Okay, Elizabeth. What is the Monuments Project and what will you do?

Elizabeth: Yes. The Monuments Project which we are really excited about has three different aspects to it. One of them is the funding of new monuments or memorials. There I want to say that we have a very broad definition of what a monument is, so we're not just thinking about statues of individual people in stone or bronze. There are all kinds of have amazing ways that figures, ideas, movements can be commemorated in our built environment, so making new things is one big bucket. Then the creation of-- The contextualization, excuse me, of existing monuments or memorials. Something that might be programmatic as we go more deeply into our history, there are ways of teaching them that gives you the layers of what these folks are all about. That gives you a counterpoint. For example, the statue of-- This is the Monuments Lab project of Frank Rizzo, the former late mayor of Philadelphia, who was among many things known for his very, very racist police brutality, and that statue stood in front of City Hall. People, citizens recently took it down, but the Monuments Lab commissioned the artists, Hank Willis Thomas to make a sculpture in response to that, so he built a Black Power Afro fist pit that was large and loomed over the Frank Rizzo, shadowing the Frank Rizzo, opening up a conversation about Black Power and Black suppression. It was up for a length of time, some months, it's now been acquired by a museum in Philadelphia, but you can see what that example how it instantly changes the conversation around that statue and also means that your average person passing by, because after all, what's really important about monuments is that we live amongst them. We come upon them. We sometimes go to visit them, but more often they are an ambient part of how we live. Another recontextualization that I think is really exciting is Dustin Klein in Richmond is doing a projection art project onto the statue of Robert E. Lee on Monuments Avenue, where he is projecting the face of John Lewis, the face of George Floyd, the face of Sojourner Truth. That you can think about as you think about Robert E. Lee up there on that pedestal, you can think about the ideologies of racial hatred that have ended in so much death and violence against Black people, but also the folks who have fought against that. Those are a couple of recontextualizations. Then we will support some people's efforts to relocate existing monuments or memorials. We don't cast our eyes upon the land and say, "This goes, this goes, this goes, this goes down with you." Rather, we work with grantees as with everything else we do, who come to us with projects, plans, visions, and ideas for how they will want to teach our history in our public spaces.

Brian: The Robert E. Lee Memorial, as it stands today in Richmond, is in its own way a pretty powerful monument. I don't know if you've seen it recently or an image of it recently, but it's covered in graffiti and surrounded by pictures of Black people killed by the police. Do you think that could ever be the monument that tells a powerful story in a way at this moment?

Elizabeth: I'm so happy you brought that up because I am really interested in not only-- I said not just single statues alone but also ephemeral monuments. Monuments that are in unofficial ways put up by communities. I think an interesting question with that will be, is this something that we think the community will do for years? Is this something that will need special tending? Is this something that will become a site of contestation? Unto itself, I think it is a wonderful thing, and when I get into the nitty-gritty of, "Is that something we would support?" Well, it might be taking care of itself, but it certainly is something that I would talk about when we think about the ways that we memorialize.

Brian: An example that I'll mention that you've cited of a more inclusive, more successful monument is Maya Lin celebrated Vietnam Memorial. I see that another of your favorites is a 1994 installation in New Haven. You mentioned New Haven called Path of Stars by Sheila de Bretteville. Want to describe anything more about either of those?

Elizabeth: Yes, I'd love to. The thing that I think is important about Maya Lin's Memorial is that when you think about it in the context of all of the outsized figures on the Mall, in that very commemorative landscape that is Washington, DC, which is where I grew up in the midst of that, to build a monument without a figure and to build a monument that rather than go up, rather goes down into the ground, that it makes a slash in the earth and that in order to experience it, you have to walk down into the earth, into that black slab which, I think, allows us not to think of war as glorious, but rather to understand war as a sight of tremendous human loss, tremendous sorrow. Then with those, I think it's now up to almost 60,000, 58,000 names that are on the wall. What I think is very interesting too is you have individual people who come and put their finger on the wall and find their dead, and have their individual experience with someone they may have loved, but then you also have the mass effect of others coming into the space and understanding what that war was all about. I think that it was really important as far as the national understanding of what a memorial could be in that it wasn't always a man on a horse, and that war itself are built in memorial landscape says that acts of war and violence are something that we celebrate over and over and over and over again, and I feel like that monument really interrupted that narrative. In New Haven, they're like Hollywood stars in the streets of the ninth ward. This is made by the designer Sheila de Bretteville. They commemorate people who were dressmakers, people who were other kinds of workers and laborers in the history of New Haven in that neighborhood, which no longer has the same activity that it once did so it has the terrific effect of allowing you to-- A phrase I use a lot is, I want to let the ground speak. It tells you this is where you're walking. This is what happened here. This is who made this place and these are people who would otherwise be forgotten, but for their family, but we're saying that they-- and there are a lot of women in those stars and we're saying remember them too. It's wonderful. I like to think that you just live with every day and if you imagine being a child walking with a grown-up and saying, "What's that? What's that? What's that? Where are we? Who's that?" I think of this Monuments Project as being for the curious six, seven, and eight-year-old walking with grownups and wanting to know what happened.

Brian: My guest is Elizabeth Alexander, president of the Mellon Foundation, as they launched their five-year $250 million Monuments Project to help reimagine the country's approach to monuments and memorials to better reflect the nation's diversity and highlight buried or marginalized stories, but also the approach to memorializing or what a monument should be at all. As Elizabeth was just describing, for example, not just making them about a single individual in every case and things like that. On this Columbus Day and/or Indigenous Peoples' Day, let's take a phone call. Judith in Jersey City. You're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in.

Judith: Hi, Brian. This is Judith. I love your show. Thank you for letting me speak. I just want to call in real quickly because I have a suggestion. I'm not trying to negate further study. I agree with that and it is also broad, but if we're going to have an Indigenous Peoples' Day, which we should, and we should get rid of Columbus Day, could we have an Immigrants' Day, which would honor both the past immigrants who struggled and the current immigrants who are struggling, and hopefully bring us together?

Brian: Interesting suggestion. Italian American immigrants as Columbus Day has come to stand for and all the other immigrants. Do we have-- I'm trying to think, Elizabeth, do we have anything that we could call a general immigrants holiday? I'm not thinking of one.

Elizabeth: No, I don't think that we do and that's such a great suggestion, Judith. I would blow it out even further because the way that we think about this in the Monuments Project is what stories are told in the landscape? Since we're not addressing the days specifically, because that's not really within our power as a foundation. As we gathered this research, from what we know so far, of all of the monuments across the land on the National Historic Register, less than 2% are of African Americans, less than 1/2 of 1% are of Latinx people, fewer than that are of Asian American people, fewer than 1/2 of 1% are of indigenous people, so things are way out of whack. That's why I think, for example, Judy Baca's project in Los Angeles, The Great Wall, answer your question about immigrant stories is an extraordinary, extraordinary one. It goes for close to a mile along a river bed telling the story of the making of Los Angeles and the people who were there and the people who came there to make it. In Manzanar, California where there was an internment camp for Japanese Americans, one of the great, great, great shames of our history. There is a memorial because can you imagine walking there and not knowing that over 11,000 Japanese Americans, mostly citizens, American citizens, were jailed there, men, women, and children. I think one part also to Judith's question of our work is thinking about the teaching museums that we support. The Arab American Museum in Detroit is an amazing place. I've been there and seen the immigrant stories that are told there. They have this beautiful way of displaying where they have old suitcases and they make displays where they have everything an individual family might have carried in one suitcase, and the suitcase becomes a display case. It's such a powerful way of thinking about immigration and what people bring with them that is material but much more importantly, what they bring with them that is cultural and historical and part of building this country.

Brian: Judith, thank you for starting that part of the conversation. Liza in Asbury Park. You're on WNYC. Hi, Liza.

Liza: Hi, thanks so much for taking my call. I just wanted to mention that I'm part of an organization called the Racial Justice Project here. We've been working with the Asbury Park City Council for the last couple of years to get Indigenous Peoples' Day on the calendar and this year it finally passed and went through so we're celebrating today at noon in Springwood Park in Asbury Park with several indigenous speakers and reps from the Sandhill Lenape Nation, some indigenous artists and one of the members of the Asbury Park City Council will be reading the Indigenous Peoples' Day Proclamation.

Elizabeth: Oh, beautiful.

Brian: Yes. What's the context of the larger work that you're involved with?

Liza: Oh, so the Racial Justice Project in Asbury Park, we've been around for the last four years doing a lot of popular education, work around systemic racism, settler colonialism. We've built up a base of people who have come to understand the relevance of the issue of Indigenous Peoples' Day, what it means, and are ready to support it on a city-wide level. We've been engaged in a lot of pop ad work as well as some campaign work [inaudible 00:27:07] .

Brian: Are you finding around this kind of issue, if you have experience with this, that there's a lot of backlash, that people are resistant to hearing it in the way you're framing it or do you think there's more openness in Asbury Park since you're working locally in that community, it sounds like, as time goes on?

Liza: Yes, definitely. I think one of the benefits of having done the popular education work for a while is that people feel like they have a grasp of the issues they have an understanding and so there is generally a lot of support. There's also a strong Italian American community in this area too and so we've also been in conversation with some reps from that community who take issue in a way, but it's all been super respectful exchange of ideas so it's going forward. Also, just to note, Asbury actually hasn't taken Columbus Day off the calendar, they've just added Indigenous Peoples' Day.

Brian: There's no more Italian American state by population than New Jersey. The Italian American community leaders who you're in conversation with or is your group and their group working on any kind of both and solution or is it not really about coming to a point but rather just communicating with each other?

Liza: Yes, I think for them there, at least what they expressed was just the desire to be heard and understood. There was a proposal put forward about doing some type of both [unintelligible 00:28:48] but that's not happening this year just because of the timing of it all. Some reps from that community will be there today at the celebration, and I anticipate it all being very respectful.

Brian: Liza, thank you so much. You contributed a lot by telling that story. Thank you very, very much. We'll take one more for Elizabeth Alexander. Mike in Manhattan. You're on WNYC. Hi, Mike.

Mike: Hello.

Brian: Hi, Mike. It's you.

Mike: Yes, thank you for taking my call. I commend the work you're doing. I think it's essential that we learn the real history of this country and perhaps what we need is something on a national scale of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to learn the real history. My one concern though is that it's maybe perhaps easier to focus on the symbolic representations like holidays and statues than it is to address the real issues of power and inequality of wealth and resources that exist today among real people. I'd be concerned about diverting too much of our attention to the symbolic when the real injustices persist.

Brian: Thank you for that, Mike. You want to respond to that and anything else from the last caller if you'd like to and then we'll be out of time.

Elizabeth: For sure. Absolutely. I hear what Mike is saying about and I think that we need to and the idea of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission would be an amazing thing because I think that there still hasn't been widespread acceptance of the cost and the legacy of more of the depth of our history. I think that we all have to-- At the Mellon Foundation, since I've gotten there, we have a social justice orientation to our work which means that every penny that we spend, it must contribute in explicit ways to a more fair and more just society. Now within that, the work that we do and that we're trained to do is in the humanities, in arts and culture, in higher education. That's where we're really pressing to have the good, hard, rigorous teaching and challenging in those fields that we know well and we work often in tandem with other funders and foundations who do other kinds of work so that each person does the thing that they do best, but trying to move the culture in what we think is a more positive and just direction. I think that the reconciliation work that was described in the caller before that is also very, very important because we need to call some tough questions. I think that when you think about something like Stone Mountain in Georgia, for example, and again when you learn that this is the most visited place in the state of Georgia, the biggest bas-relief in the country with these Confederate figures on it that it was built into a mountain owned by a Klansman. That it was the-- One of the artisans with a Klansman. That the klan continued to reassert itself as an organization and have its rebels and cross-burning atop Stone Mountain, terrorizing the people beneath. That's where I say that statues really do matter. That the environment that we live in, that we look at every day, it teaches us. It teaches all of us. What do we want to teach people? I think me, myself, Elizabeth, I believe that the symbolic and the figurative that we live amongst has tremendous power. I think if you stand next to something large that venerates someone who doesn't recognize your humanity, you are being taught that you are small. I think that matters. Similarly, and this was a wonderful Monuments Lab project that was in Philadelphia. They had two pedestals with very accessible-- They were properly disability accessible and you could climb up upon them and [unintelligible 00:33:33] . [chuckles] They were secret corners, but monuments pedestals and there are wonderful pictures of kids, little people getting up and feeling, "This is what I believe. This is who I am." Of feeling large, of feeling like their voices matter. I think that that's really exciting and I think we're going to get something done and it's going to be fascinating.

Brian: Let's hope. Let me throw in one follow-up to that answer and the callers suggesting that there's too much focus on monuments and memorials. Just last night, protestors in Portland, overturned statues of Theodore Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln in a declaration of rage toward Columbus Day. Protestors spray-painted "Dakota 38" on the base of Lincoln statue referencing the 38 Dakota men Lincoln approved to have hanged after the men were involved in a violent conflict with white settlers in Minnesota. Does that thing undermine the politics or public reception of the whole project that you're involved with and are just describing when even Lincoln gets targeted? Certainly, the president and others are using that, or is that part of the necessary conversation?

Elizabeth: I think it can all be part of the conversation. I think it's just really important that we-- People must be responsible for their deeds. We must know their deeds. We must know them in their complexity. Then we can think about, again, where, how, how many? In Washington DC, in Lincoln Park, there's been some really interesting controversy because there's a statue of him where he is freeing the slaves, if you will, with one representative kneeling and I think semi-clothed Black man at his feet. Some people are saying that the Black man is not a dignified position. That statue should be taken away, but what I think is interesting about that space is that right across the park, a statue of the Black educator, Mary McLeod Bethune, with Black children who she's teaching ostensibly the legacy of the end of slavery. Look, right across in the eye to Abraham Lincoln and that when the Lincoln statue was put up, Frederick Douglass gave a speech in that spot where he had a very critical and complex assessment of Abraham Lincoln. I think a final interesting part would be, maybe even just a plaque or that could help teach that part of things. I just think that this is not-- Our history is not simplistic. The people who we raise up are sometimes complicated, but let's start off by giving us a much wider range of people to think about. Harriet Tubman [chuckles] is someone who all Americans, all people should be able to identify with what it means to believe in freedom and what it means to risk your life over and over and over again to lead other people to freedom. That's just one example of a figure who doesn't belong just to me or to another Black woman but belongs to everybody.

Brian: Elizabeth Alexander, president of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. Thank you so much.

Elizabeth: Thank you so very much.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.