The Ideological Differences Between Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X

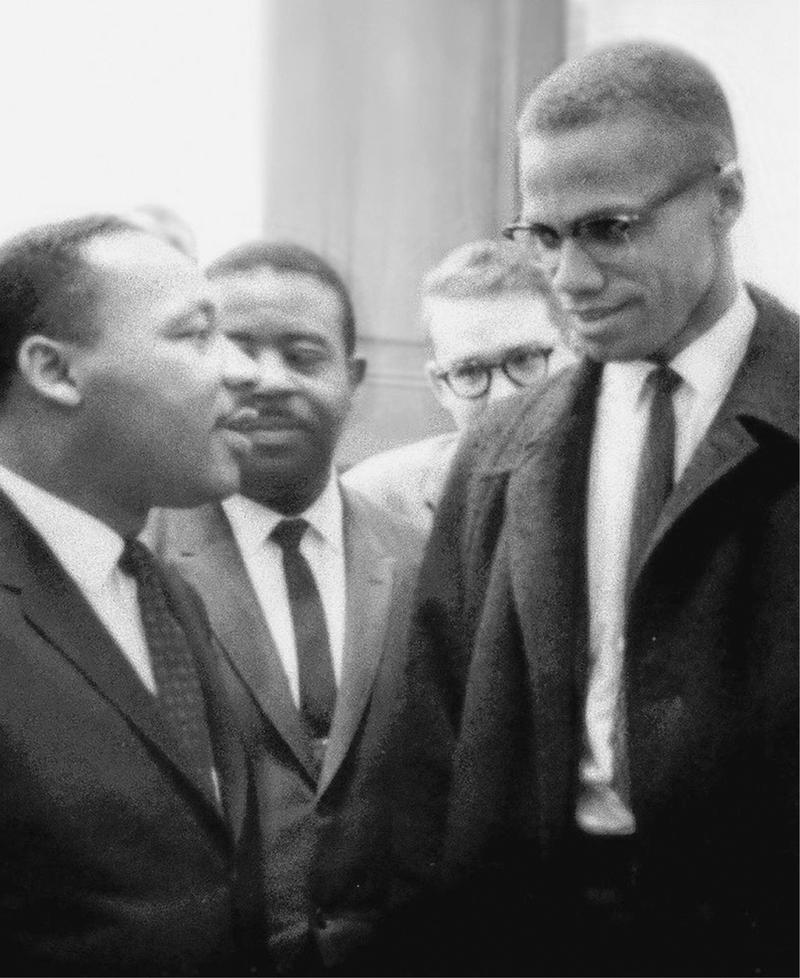

( Photograph by Marion S. Trikosko for U.S. News & World Report magazine, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division )

[MUSIC]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Here in Black History Month, one of the new things on TV is a new season of the National Geographic series, Genius. In the past, they've done Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso, and Aretha Franklin. This season's series is called Genius: MLK/X about Martin Luther King and Malcolm X. It's also about their wives, Betty Shabazz, and Coretta Scott King, and the vital roles they played in the struggle and in their husband's work. This is not a documentary series though, it's an acted series. Here's a 30-second sample of Aaron Pierre as Malcolm X.

Aaron Pierre: Now, I've been to Detroit, Philadelphia, Chicago, and even for our Southern folks here, Edgewood. The same truth exists up and down this so-called land of the free. We're all still negotiating something that should be ours, so what's the solution? Pride and dignity within self.

[applause]

Aaron Pierre: Caring about who we are, and when we understand our worth and have pride within it, so too will everyone else.

Brian Lehrer: Aaron Pierre as Malcolm X in the National Geographic series Genius: MLK/X. One of the points of the series is to portray how the public images of the two men are too often reduced to oversimplistic contrasts of King, the unifier, and Malcolm, the militant.

We'll talk now to a special guest who is a consultant to the series and wrote a book that inspired it, a many-time guest on this show, Peniel Joseph, professor of history and public affairs and founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of books including The Third Reconstruction: America's Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century, and the one directly relevant to Martin and Malcolm, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. Peniel, always great to have you with us. Welcome back to WNYC.

Peniel Joseph: Hey, great to be back, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: First, what's your relationship to the series? Tell us more.

Peniel Joseph: During the pandemic when we were all just shuttered and reading a lot of books, the producers, they approached me and they said they were excited about the book and that they were actually going to be doing a series. I think initially they had thought of just doing MLK, and the producers who they were working with at Undisputed Media, Reggie Rock Bythewood and Gina Prince-Bythewood, they wanted to do both, and they had the source material to do both with The Sword and the Shield.

From then, we were in a writer's room through Zoom, and I was able to visit the set. [inaudible 00:03:14] what I thought, and I think they did a really great job [crosstalk].

Brian Lehrer: Very exciting.

Peniel Joseph: Very exciting, yes.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, you're invited in in this segment for some oral history for our latest Black History Month segment. If you were alive and paying attention during the lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, did you tend to line up more with one or the other? If so, why at the time? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. For anyone, how has your understanding of Malcolm X or Martin Luther King changed over time? Do you see them as less different today than you might have when you first thought about them?

Also, you can call in if you've been watching the National Geographic series Genius: MLK/X. The first four episodes have been out. I believe the latest two are dropping today. Anything else you want to say or ask our guest, Peniel Joseph, from the University of Texas at Austin and author of the book, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr?

Would love to get some oral history here from people old enough to have been around during their lifetimes and have had impressions of them at that time and if they have changed for you. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Peniel, you write about their very different childhoods and the geographical and religious contexts of their youth to help understand why they entered public life with the messages that each of them had. Can you describe a little bit of that?

Peniel Joseph: Certainly. They both have, in their own ways, traumatic childhoods, certainly, and very, very blessed childhoods as well. Malcolm is born in Omaha, Nebraska in 1925. His parents are Garveyites, which means they're followers of Marcus Garvey who is this Black nationalist, Pan-Africanist, interested in political self-determination, also Black people owning their own businesses and defining their reality for themselves.

His mother is from Grenada, a very light-skinned woman, who could really pass for white. His father is from Georgia, very dark skin. They end up having seven children. His father has three children from a previous marriage. They are farmers. His mother speaks five languages and teaches the kids French and how to read and how to write. They're also terrorized by the Klan and different white supremacist groups because they consistently move to predominately white areas because that's where the better infrastructure, better land is.

Eventually, Malcolm's father is going to be killed in 1931, something that he always remembers as a lynching. Other people say he was killed in a streetcar accident, but Malcolm is only six years old. That's going to really transform the course of his life because by the time he's 13, his mother is going to be placed in a psychiatric institution in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and the family is really going to be broken up.

From there, he's going to go visit his sister, his half-sister, Ella Mae Collins, who really becomes two of the most important women in his life. Beside his mother is Ella Mae Collins and his wife, Betty Shabazz. That's his childhood. He becomes, by the time he's 14, 15, what people would call a juvenile delinquent and engaged in fits of criminal activity, both in East Lansing, but also in Boston, Roxbury where he moves in with his sister, and Harlem. Then he's finally arrested. He's arrested numerous times, but he's placed in jail in 1946.

It's in jail that he's going to have that jailhouse conversion to the Nation of Islam and Elijah Muhammad, and becoming a Muslim. Where King, in contrast, is born about three and a half years after Malcolm in Atlanta, Georgia, in 1929. He's the son of a-- Really, his father is a sharecropper. It's really sharecropper's people who becomes a reverend. His father is from Georgia, just like Malcolm's father was from Georgia, and like Elijah Muhammad was from Georgia, so very interesting convergences.

King's mother is part of the Black elite and her father, his maternal grandfather, was the founder of Ebenezer Baptist Church, which is still there in Atlanta today. Reverend Raphael Warnock, the senator, is at the pulpit of Ebenezer. When you think about King, he has a much more gilded childhood, goes to good schools, wins oratorical contests, enters Morehouse at the age of 15, but as the series shows, he had two suicide attempts at a very, very young age. He experiences racial discrimination. He experiences depression.

When he's 10 years old, King dresses up as an enslaved boy at the Gone with the Wind premiere in 1939 at Ebenezer Baptist Church. The whole choir is there really in a minstrel show capacity. Malcolm is seeing that same film in Mason, Michigan, and feels so humiliated. He writes in his autobiography he felt like crawling under his seat because he goes with his predominantly white classmate to see Gone with the Wind.

What's so interesting about both of them is that they experience race in different ways and in different localities, but they become people who are very much identified with Black people and identified with the poorest of Black people. They become people who are on the side of the underdog, on the side of the most marginal, and discriminated against Black people.

In Malcolm's case, it's prisoners and people who are formerly incarcerated. In King's case, it's going to be sharecroppers and people semi-literate, illiterate who are considered less than human in society.

Brian Lehrer: Let me take an oral history call. Kathleen in Norwalk, Connecticut, who recalls seeing Malcolm X speak in his lifetime. Kathleen, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Kathleen: Hi, Brian. Yes, as I was telling your screener, I went to Barnard College, which is-- obviously, it's privileged and it's girls. A group of women invited Malcolm to speak at Barnard, and I was thoroughly expecting to have him take us to task for being white and privileged. I will never forget the grace and really the love. It was an aura. I will never forget his face, his demeanor. He had come back from his Hajj where he found that he had brothers and sisters who were white, Black, yellow. His community with them was the religion of Islam.

I felt that Martin was coming the other way from being mainly spiritual guidance and that sort of thing, but then when he got involved with the garbage workers and the striking that they were going to hold, he was heading toward the more economic answers. It's Malcolm that I remember so well, and I think had they lived, of course, that's why they didn't live, things would've been really, really different. I just was in awe of the presence of Malcolm X.

Brian Lehrer: Kathleen, thank you.

Kathleen: Unfortunately, I never got to see Martin.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you so much. Peniel, can you talk about-- The caller was starting to get at it, and I think this is important to the TV series and to your book. Talk a little bit about how each man moved toward the other.

Peniel Joseph: Oh, absolutely. Malcolm, his big contribution is this idea of radical Black dignity and that all people had human dignity, but Black people were the universal principle in that because he felt if Black people had dignity, then all people were going to achieve it. King's notion was of citizenship, radical citizenship, and that citizenship meant beyond voting rights and civil rights, but an end to violence, healthcare, a living wage, all these different things that he's going to believe in.

Over time, Malcolm, when you see the ballot or the bullet comes to believe in citizenship, he comes to lead voting rights, rallies. He also becomes this revolutionary Pan-Africanist and human rights activist, a critique of capitalism, an anti-imperialist, so this real revolutionary. Over time, King does too. What's so interesting is King comes to believe in Black dignity. He comes to start saying that Black is beautiful. King is never anti-white, so he never used some of the white devil language that Malcolm used when he was part of the Nation of Islam, but King comes to be a huge critic of white supremacy.

When we see both King and Malcolm by the mid-60s, and they meet at the US Senate building on March 26th, 1964, you're seeing this overlap of citizenship and dignity. King wins the Nobel Prize that year, and that's the year that Malcolm spends five months in Africa. The caller before alluded to the Hajj, and the Hajj is very important because they were both men of faith. A lot of times because of this country's Islamophobia, we don't give Malcolm the credit as somebody who is a Muslim minister for the last 17 years of his life.

Malcolm doesn't see a disconnect between his time in the Nation of Islam and becoming a Sunni Muslim. He sees it as a continuation and evolution and expansion of his mind. He always says that he didn't change but travel broadened his mind. He takes the Hajj, he takes the Umrah, the mini Hajj in September, the first Hajj in April, and he meets extraordinary leaders.

He meets leaders of Nigeria and Kenya and Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah and Nnamdi Azikiwe, Prince Faisal of Saudi Arabia. He meets up with President Nasser of Egypt. He is a very, very interesting person in that sense that he becomes this unofficial prime minister of Africa in America overseas. He's also arguing and making a point to Muslims and Islamic clerics that they need to be anti-racist and on the side of racial justice. If not, the religion that they're articulating is not the religion of justice and truth and equality as they claim it is. He's really challenging everybody at the end.

Brian Lehrer: Our time has gone so quickly. We have a minute left. One more listener comment via text. It's a question, really, "Curious how your historian guest justifies the anti-historical use of actors, their faces, their voices to imitate people of whom we have archival audio and video." This is TV dramatization, not history, and that series on National Geographic is TV dramatization. I don't think they hide that fact. Do you want to say anything to that listener?

Peniel Joseph: Oh, yes. That's art. History can be the basis whether it's about Dr. King or the American Revolution or the Civil Rights Revolution. This is not a documentary, and this is reaching so many millions of people. I think it's really important to allow actors and the artists that we have to convey these historical figures. Denzel Washington does a brilliant job in 1992 in the Spike Lee film, but this is really updated for the 21st century and shows the way in which both of these folks were dual sides of the same revolutionary coin.

Brian Lehrer: There we leave it with Peniel Joseph, founding director of the Center for the Study of Race and Democracy at the University of Texas at Austin, and author of The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr., inspiration for the new National Geographic Genius series, MLK/X. Peniel, thanks as always.

Peniel Joseph: Thank you, Brian.

Copyright © 2024 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.