How Pop Music Influences Americans

( Suzanne Plunkett / AP Images )

Brian Lehrer: Well American music encompasses all different genres jazz, daz, blues, country, rock, hip-hop, and the list continues. What holds all of these genres together throughout the history of popular music in the United States? Ann Powers, NPR's music critic argues in her new book Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music that popular music has allowed Americans to communicate emotions and truths about difficult social issues and sex.

Her book takes us on an adventure starting from 19th century New Orleans through the Jazz Age to rock and roll and today's web-based stars exploring how they helped shape American culture. Hi Ann, welcome back to WNYC.

Ann Powers: Hey, Brian a pleasure to talk to you again.

Brian: Let's start with the enticing title of your book Good Booty. As I understand, this is a reference to Little Richard's Tutti Frutti.

Bop bopa-a-lu a whop bam boo

Tutti frutti, oh Rudy

Tutti frutti, woo

Tutti frutti, oh Rudy

Tutti frutti, oh Rudy

Tutti frutti, oh Rudy

If I hear them correctly and the way I've heard it over the years Little Richard singing Tutti Frutti or Rudy not good booty.

Ann: [chuckles] Well, yes, but originally before he recorded that song, Little Richard would sing the original version which did include the phrase good booty and was a reference to, well, pretty much exactly what you think. Let's just say another lyric he excised was if you grease it, make it easy. I don't think he was talking about frying chicken right then. It was a song that was popular in nightclubs in the South. Little Richard toured a lot in the South and toured with transgender performers. I learned a lot from queer performers like Esa Carita and took that into the studio. It was considered too racy.

He and a young woman named Dorothy LaBostrie rewrote the song and made it into nonsense which anyone who knew it knew what was under it.

Brian: In the very first sentence of your book you describe the moment when you were nine years old and realized music was sexy. That music was an outlet for you to feel good physically. Do you still get this feeling when you listen to today's popular music?

Ann: Well, of course, I'm still human being and I'm still alive all these years later, [laughs] so I do. I think one of the wonderful things about music is an art form that we carry with us throughout our lives. It means one thing to us when we're very young and another thing when we're young adults, and another thing when we're mature adults as I am today, I suppose, in midlife. That spirit and joy of the body and physicality is always present. Sure especially when I'm out there on the floor dancing, which I still try to do when I can.

Brian: You write that the 20th century really saw the opening of sexuality in our country, but it was initially only revealed through public dancing. Ethel Waters the famous jazz singer sang That Da Da Strain. Let's take a listen to a few seconds of that song.

Have you heard it, have you heard it,

That Da Da Strain?

It will shake you, it will make you

Really go insane.

Everybody’s full of pep,

Makes you watch your every step.

Brian: [chuckles] Everybody's full of pep, makes you watch your every step. What year was that from?

Ann: Oh my goodness. I don't have the book in front of me, mid-20s. I'll tell you, the thing about that song and that era is that it was a time when sexology was coming into popularity. Sexology was the science of sex made accessible to ordinary Americans. This was an era when you had marriage manuals, when you had people talking about how to make their marriages more lively in the bedroom and dancing and songs like that one which describe dancing. Really were a parallel and a way of talking about what was going on in the intimate lives of Americans at that time.

Brian: The phrase from the title Da Da Strain is that euphemism like Tutti Frutti or Rudy.

Ann: Exactly, [laughs] exactly. That’s something that runs throughout my book too. The use of nonsense in lyrics to invoke sexuality partly because of course there are obscenity laws and you can't necessarily say the most explicit things which is still true on the radio, for example. The 1950s, you have another wave of this with Doo-wop music and the nonsense syllables of Doo-wop music.

Not wop but [unintelligible 00:05:01] Rama Lama Ding Dong and all that kind of phrasing was a way of expressing feelings and impulses that otherwise couldn't be talked about.

Brian: Another genre gospel got a more modern twist in the mid-20th century creating what you described as a space where the beauty and poeticism of desire was revealed. You point out specifically Thomas Dorsey’s Take My Hand, Precious Lord evoking the power of gospel. Here's a cliff.

Let's go.

I love your name,

When I look back,

[unintelligible 00:05:52] I can.

Now that's devotional music which we might think of as the opposite of music rooted in desires. Is there some intersection?

Ann: Absolutely. I argue that when the Golden Age of gospel began with Thomas Dorsey leading the way with intimate songs like Precious Lord Take My Hand. The energy and power of the Blues combined with the urge toward transcendence of sacred music to create this new form that then when secularize became rock and roll and soul. I'm not the first to argue this. People talk a lot about Ray Charles’s music as transforming gospel into something secular. This happened with Little Richard. It's certainly Elvis Presley was hugely influenced by gospel. I think today we have forgotten about this for some reason. Again, gospel has retreated for a lot of people into a separate realm, but I really want it to get all the credit it deserves as being fundamental to 20th-century music in America.

Brian: If you're just joining us, my guest is NPR's great music critic, Ann Powers. Her new book is called Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music. We’ll hear some more clips as we go but you dubbed the ‘50s as the decade of teen dreams and grown-up urges that rock and roll represented fantasies of growing up for teens. Certainly, not new there. How did rock and roll break the bonds of conventional gendered behavior though?

Ann: Well, one thing that happened is that girls really came into power as fans not so much as performers. There were great women performers in the ‘50s like Wanda Jackson, for example, the Rockabilly Queen. Young girls were the engine behind rock and roll. This is often acknowledged in the ‘60s with Beatlemania. We think of those screaming throngs of girls, but it was actually very true in the ‘50s

They were truly running the mechanisms of rock and roll. They were running the fan clubs. They were inviting artists to their town. Young women were often editing the fan magazines that were getting the word out about these rockers.

Really the girls are asserting themselves. They're trying to negotiate their own sexuality, which the ‘50s was a complicated time. I guess my insight into that era is that rock and roll isn't just about liberation. It’s also about dealing with anxiety, dealing with fear of sex, and fear of this new frontier that was facing teens. Teens were dating very young in the ‘50s much younger than they had in previous decades because of the war. They were encouraged to date in this post-war era to make sure that the family survived. At the same time girls were supposed to remain virgins until marriage, so there was a lot of contradiction.

Music of Elvis or say the Everly Brothers articulated those contradictions beautifully.

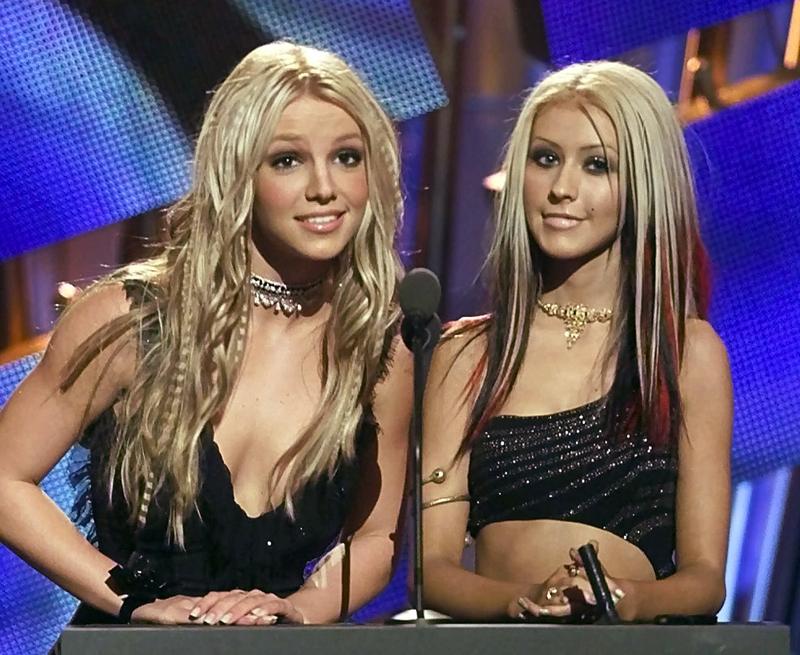

Brian: We're going to skip ahead many decades to sort of the ‘90s to today. One of the main technological influences in music has of course been the synthesizer. It's almost replaced the electric guitar, which is another show I think. Britney Spears uses it often through her career and an example you give us her 1998 hit song Baby One More Time.

When I’m not with you I lose my mind

Give me a sign, hit me baby one more time

You write about how [unintelligible 00:09:37] sound and some of the dance hits like Baby One More Time suggest how we perceive sexuality today?

Ann: Millennials are the first generation to really grow up as digital natives completely absorbed in and connected to the technology of cyberspace from the minute they start forming their identities and that has changed the way they relate and we relate to sexuality as well. I don't have to mention, there's certainly plenty of sexually explicit material on the web, but even besides that, and besides internet dating and all of that, just forming a different identity, an augmented identity through the web really changes your sense of self. Britney Spears whose voice has always been so processed and connected to synthesized sounds, her producer, Max Martin, talks about her voice as the perfect compliment to synthesizers. That is the sound of this augmented cyborgian self.

Brian: I want to go back to the 19th century now. We've been progressing chronologically on the sexual track, but you start the book in 19th century New Orleans with a discussion of the relationship between American music and the oppression of African-Americans.

Ann: Yes, that was really key for me. I was writing this book during the time when the Black Lives Matter movement really came to the fore. I mean, at any time I would have written this book this would have been a central theme, but it's been so much on our minds, even your last segment, Brian, we're talking about these issues. One of the reasons why popular music became a conduit for these conversations about eroticism and the body, things we have a hard time talking about, is because it was always a conveyor of secrets and legacies that would have been lost for Africans enslaved in this country, as they became African-Americans throughout the antebellum period into reconstruction and Jim Crow.

Music is a way that African-Americans have retained dignity, pride, and joy. I think I, as a white woman, owe everything to that tradition. Everything I love in music comes from that legacy and I really hope that I did justice to it talking about it in this book.

Brian: One example is that you write about the genre of rap coming from a place where its creators desperately needed a cultural space of their own and one example was the '80s hip hop group Public Enemy known for their politically charged music that reflected some of the frustrations and concerns in the African-American community. Here's 15 seconds of the 1988 single Don't Believe The Hype.

The minute they see me, fear me

I'm the epitome, a public enemy

Used, abused without clues

I refused to blow a fuse

They even had it on the news

Don't believe the hype

Brian: A pivotal moment in music as well as social history?

Ann: Yes, absolutely. I mean, the rise of hip hop changed the sound of popular music forever. Changed the way that we make music today by introducing the sample and the turntables and making rapping which was actually, of course, very old style of vocalizing. You can trace it all the way back to the dozens the [unintelligible 00:13:17] games that people played in the street at the beginning of the 19th century, but it changed everything.

As far as its relationship to sexuality, it's complicated. In the '90s, rap was very masculine, very masculinized. There have been great women rappers, but often they were put in the position of almost fighting a war through their raps. Hip hop is a whole world unto itself. It goes beyond the scope of my book but definitely is central to the story of what music has become in this century.

Brian: Since you referenced the current event's conversations from earlier in the show regarding recent events, even last week in Charlottesville, do you see music as providing a way to cope with everything?

Ann: I think the most profound example is what I end my book with, which is Beyonce's album Lemonade. I wrote the epilogue to this book after I had turned in the manuscript, but Lemonade had such an impact on our culture and really made this perfect circle with where my story begins, because Beyonce writing about New Orleans, making her visual album takes place a lot in Louisiana, and she was returning to that origin, that foundation that I'm talking about, the legacy of African diaspora music that today she is connecting through her very personal, but also political music with songs like Formation that are inspiring a new generation's pride in their bodies, in their booties, in every aspect, but also in their souls.

Brian: To go way back in history. Again in the book, you tell us of the magazine writer, Kate Chopin, is that how she says it?

Ann: Yes.

Brian: Her tragic story of La Belle Zoraïde.

Ann: Zoraïde, yes.

Brian: Can you go to the tale a little bit?

Ann: Oh, yes. Well, this was an interesting stream that I went down. I found this legacy of Creole songs from the 19th century that were tales of domestic life involving enslaved people and often their mistresses, or sometimes their masters, or else it was relationships between enslaved people. Very intimate private stories. These songs were sung in the home. They were transcribed and published in magazines. It's unclear of their authorship, but they seem to tell a very intimate story about the private relationships of the antebellum South.

It's great that you brought it up right now, Brian, because I think that Beyonce's Lemonade in a way without necessarily intending to reconnects with this tradition. She identifies as Creole and Creole culture and Creole consciousness. The consciousness of a people of mixed race is so essential to this country and essential to our story of music because music is in itself a hybrid.

Brian: That relates to Formation from Lemonade which people saw at the Super Bowl?

Ann: [chuckles] I think it does because when you think about Beyonce's message of pride in African-American womanhood, pride in her own generation, she wants us to remember our history. She wants us very importantly to remember the pain of our history as well as the joy. She told that story mostly on Lemonade through the private story of her marriage to Jay-Z, problem she had in the marriage, and how they recovered, but also always connecting with those larger social issues which-- See my definition of the erotic connects with the great writer, Audre Lorde. It's about personal power, the resilience to survive oppression because you have a wholeness within yourself. I know there's a lot of hype around Beyonce, but I do think she does embody this in our time

Brian: Ann Powers, NPR music critic, author now of Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black and White, Body and Soul in American Music. Awesome. Thank you so much.

Ann: Thank you so much, Brian.

My daddy Alabama, Momma Louisiana

You mix that negro with that Creole make a Texas bama

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.