How Polio Showed Up in Rockland County

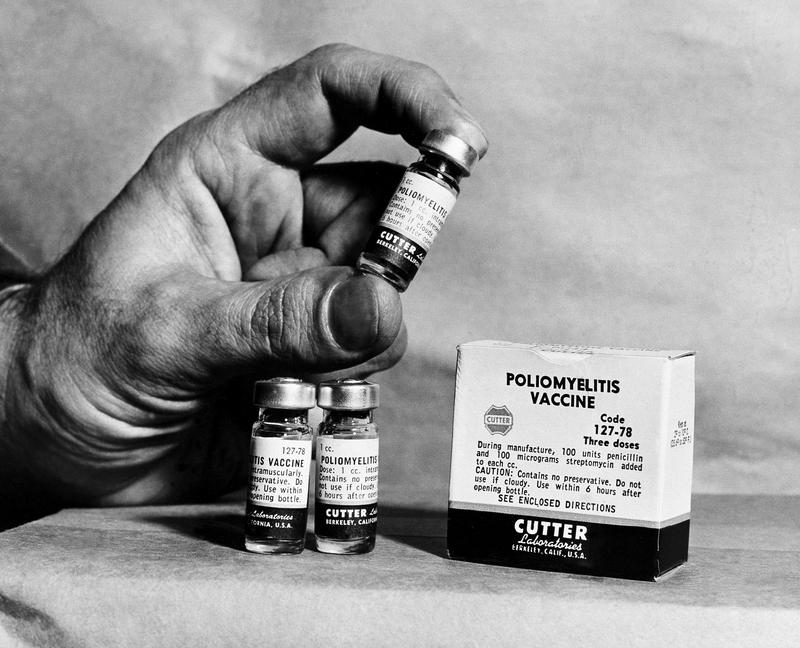

( AP Photo )

[music]

Brigid Bergin: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Brigid Bergin from the WNYC and Gothamist Newsroom filling in for Brian today. While we're still in the thick of the COVID pandemic caused by a new virus, there's news of a young man in Rockland County stricken with an old virus, one that was thought to have been eliminated in this country, poliovirus. Depending on your age, you might remember when it caused panic in this country in the 1940s and 50s until a vaccine was developed in 1955.

This young man, and very little information has been released about him, has developed paralysis. To find out more about this virus and the disease it can cause, we're joined by Alan Dove, a science journalist with a PhD in Microbiology, who is one of the co-hosts of This Week in Virology, TWiV Podcast. Welcome to the Brian Lehrer Show, Alan.

Alan Dove: Thanks. It's good to be here.

Brigid: Let's start with how this young man is thought to have been infected. He was non-vaccinated against polio as a child, unlike something like 80% or 90% of American children, but he probably caught it by way of someone who was vaccinated in another country. Can you explain the route that probably led to this infection?

Alan: Right. It sounds like a simple question, how did you catch the virus? In this case, we have to step back and understand how poliovirus works and how the vaccines interact with the virus. There are two different vaccines for polio. Poliovirus like a lot of viruses, it's a gut virus. It normally transmits by something we call the fecal–oral route, which is a very unappetizing name for it, but it's an extremely common route of infection. Anybody who's spent any time around kids understands that they're very bad about hand washing, but adults are good at this too at spreading these viruses. What happens is you get some fecal contamination often on the hands, it can also happen when sewage systems are not sufficient.

Then one way or another, the virus gets into the mouth, goes to the gut, and that's where it replicates. It replicates in the intestine and then is spread in the feces and moves on through the next cycle. Now, most of the gut-borne viruses that spread this way, there are hundreds of viruses that spread this way, that's all they do. Really in most cases with poliovirus, that's all that happens. It's a gut virus and that's how it goes along. What's distinct about polio, though, is that in some cases, probably in about a half of 1% of people who get infected with it, that gut replication progresses to spread into the bloodstream, the virus replicates there, gets into the nerves and does nerve damage that causes paralysis.

It may sound like, "Well, it's only a half of 1%, why don't we just take our chances?" The problem is that this virus spreads so well in a population when nobody's vaccinated like back in the 40s, that pretty much everybody will get infected. Then if you're talking about 0.5% of everybody, this adds up to entire hospital wards full of iron lungs, which you may have seen historical photos of. That's the normal life cycle for polio. The vaccines, so there are two vaccines available. There one that's used in the United States and pretty much all other developed countries is the one that was originally developed by Jonas Salk in the 1950s, was released in 1955. This is the inactivated polio vaccine. It's basically the simplest way you can make a vaccine.

You take the virus itself, the wild-type poliovirus, and there are various ways it can be done, Salk originally used formaldehyde to inactivate it, the newer enhanced version uses different procedures. The upshot is that you completely inactivate the virus, it cannot replicate, but it still has the same shape as it normally does. You inject that into somebody's arm and their immune system sees it as foreign and responds to the foreign antigen by generating antibodies that generates a very durable bloodborne immunity against the virus so then if that person gets infected with polio, it starts replicating in their gut, if it starts to spread to the bloodstream that bloodborne immunity stops it, and the person is protected from developing paralysis.

Brigid: Why is the live virus vaccine still used, and where is it still used?

Alan: The other vaccine was developed by Albert Sabin. It was released in 1961, I believe. That uses a different process. Instead of using the wild-type virus, Sabin took that virus, cultured it in the lab repeatedly under different conditions. As viruses replicate, they accumulate mutations, and because it was growing in the lab, it accumulated different mutations from what it would in a normal host and became attenuated. Meaning it lost the ability to invade from the gut into the bloodstream and the nervous system. The Sabin virus is actually given orally. This is a live virus vaccine, it's not inactivated, it's able to grow, and that's actually part of the point.

You give it to somebody orally, just the way they would contract polio. It goes into their gut, it replicates, the immune system in the gut and in the bloodstream detects this and responds to it, stops the infection and that's all well and good, and that produces very durable immunity. There are advantages and disadvantages to each of these vaccines. As I hinted at already, the injected vaccine, the inactivated vaccine generates the bloodborne immunity that prevents you from getting the disease, but you could still act as a carrier of poliovirus because you don't have the gut immunity because you haven't actually had the virus replicated in your gut.

The oral vaccine confers both types of immunity, which means people who get the oral vaccine don't act as carriers, and they're also protected. The big disadvantage to the inactivated vaccine is that in order to deliver it, you need a medical infrastructure that can deliver shots. The sad fact of the world today is that there are a lot of places where that infrastructure doesn't exist. In those cases, you would prefer, and in fact, it's not just the polio vaccine, it's all the vaccines that have to be injected that are not able to be delivered to remote, especially rural areas of poor countries is really, really a difficulty.

Brigid: Listeners, we can take your questions on polio for journalist and virologist, Alan Dove. Do you have questions about the virus and how it's spread? If you're old enough to remember the relief that followed that introduction of the polio vaccine, we'd be happy to hear from you on that too. Tweet @BrianLehrer or call us at 212-433-WNYC, that's 212-433-9692. Alan, in talking about this case out of Rockland County, how worried should we be about this case and the potential for a spread?

Alan: Not very. What happens, the big disadvantage of the oral vaccine, the big advantage is it can be delivered orally so you can get it to poor countries. Also, from a parent's perspective, you're probably aware if you gave a child a choice between getting a shot and getting a sugar cube with a couple of drops of liquid on it, they'd probably pick the sugar cube. There's that advantage.

The big disadvantage of the oral vaccine is because it replicates in the gut, it reverts some of those mutations that it accumulated to become attenuated. It is the only vaccine still in general use that can cause the disease that it's meant to prevent. That's what's happened here in this Rockland County case. There's not a whole lot of information and it's appropriate there's not a whole lot of information because it wouldn't be right to identify the patient.

Brigid: Just to clarify, when you're saying-- so this person who contracted the case was most likely exposed to someone who took this live virus, the oral version of the vaccine, and because this individual was not vaccinated, that is what enabled this individual to contract this case of polio most likely. Is that correct?

Alan: Yes, that is. That is a scenario that we see not very often in the US, the last case we had like this in the US, I think was 2013. It does come up in areas where they're still trying to eradicate polio, particularly in developing countries where the oral vaccine is in wide use and yet you don't have full coverage, maybe you're covering 80% of the population or 70% of the population and the unvaccinated people who get exposed to those folks who just got vaccinated can then contract what we call a vaccine-derived poliomyelitis.

Brigid: Officials are offering vaccines to adults in Rockland County who are unvaccinated and urging parents to get their children vaccinated with their pediatricians. I saw that FDR contracted polio at the age of 39. This is not just a childhood or young adult illness. Correct?

Alan: Correct. In fact, there's a strange phenomenon that happens here where we think of polio epidemics in the 30s and 40s. Polio has actually been with humans for thousands of years. There's evidence it was spreading in ancient Egypt, but it wasn't really noticed a lot. There was a high background of morbidity and mortality for a long time, but in addition, there's some evidence that if somebody is infected very, very early in life, like in infancy, their chances of getting a paralytic case of polio are lower than if they're infected a few years later.

What probably happened or what may have happened and we can't really go back in time and figure out that for a certainty, but it seems that as we improved our sanitation in the early part of the 20th century, we delayed that early exposure to the virus, and made it more likely that people would acquire it later. Also, we had better medical surveillance and were noticing, "Hey, people are getting paralyzed." FDR had somehow managed not to get polio earlier in life. Of course, the vaccine was not available for his generation and then in his 30s, I believe had a nice day swimming and then got sick and then ended up in a wheelchair for the rest of his life.

Brigid: Right. Alan, we've got a lot of callers with some questions. Obviously, I will note, and as I'm sure you will too, that you are not a medical doctor, you're a virologist and journalist. In the context of some of these medical questions, we are not dispensing medical advice here, but answering questions from a more academic perspective. Bob from Parsippany, New Jersey has a question that you may have a perspective on, but clearly Bob, you probably need to consult with your physician for the best advice in this case, but in a more academic sense, Bob, can you pose your question to Alan?

Bob: Yes. I asked this question to three different doctors. I got a split decision. I'm 77 years old. I was never vaccinated for polio. My parents apparently read the papers and there were several deaths after the introduction of the first vaccine and they decided not to get me vaccinated, so should I get one now?

Alan: Well, with the caveat that this is not medical advice, I would say, if it were me, I'd go ahead and get it. The inactivated vaccine, the shot that's given in this country basically your risk of side effects is your arm will probably be sore for a couple of days. It's like getting a flu shot. At this point, it is probable that you've been exposed to either the virus or a vaccine-derived virus. The US actually used the oral vaccine up until, I believe the year 2000. If you've been around kids or grandkids who were vaccinated, they were probably shedding live vaccine virus.

One of the things that happens with the oral vaccine is that it can give a what's a secondary vaccination where somebody, gets the vaccine from changing a diaper or something. I would think, again, not medical advice, but just from my own perspective, if I were in your shoes, I'd go ahead and get the shot.

Brigid: Bob. Thanks so much for calling. Let's go to Emma in Brooklyn. Emma, welcome to WNYC.

Emma: Hi, how are you guys?

Brigid: We're good. I understand you have a family connection, a family history of polio. Is that correct?

Emma: Yes. So, I'm 35 and my grandma was born in 1907 in England. She actually developed polio halfway through her life when she was 45 and my mom was five years old and it totally upended her entire life. My mom has grown-- I actually wish my mom was on the phone, but I'll speak for her because it really traumatized her and her mom could no longer go upstairs. These are very basic things, but could no longer go upstairs to take care of her, so they had to move into a new house that was accommodating.

In the 1940s, it was a very different time period obviously, but I heard the sentiment about not wanting to vaccinate has been gravely concerning her and is actually, in some ways, I think triggering some previous trauma from her childhood because she was so young when it happened and then had to just completely take care of herself. I feel like this is probably something that people who have lost family members to COVID can relate to, but just the idea that polio is coming back, there's nothing to say. My grandma couldn't do anything on her own for the rest of her life.

She was in a wheelchair, she had to have aides help her into bed every day. That was in England and they have sure free health insurance, so it's a totally different-- the resources are a lot larger. This is when I knew her, when I was-- in the 90s.

Brigid: Emma, thank you. [crosstalk] Go ahead.

Alan: This is a debilitating virus and the reason that developed countries have switched over to the inactivated vaccine is even though the risk of the oral vaccine causing polio is extremely small, it's something like one in two million vaccinations. When you get to the point where you can deliver a vaccine that doesn't even cause that, the cost-benefit ratio just favors it. That's what we went to because this is something that will destroy someone's life.

Brigid: Emma, thank you so much for calling and sharing that story. I'm sure your grandmother's impact has certainly had an effect on your life and your understanding of vaccines. I think it's something that for some people, it's more in their memories, in their consciousness than for some others. Let's go to Louise in Brooklyn. Louise has a question related to whether older adults still have immunity if they got vaccinated. Louise, welcome to WNYC.

Brigid: Yes. Hi, Brigid. Thank you. I seem to remember having gotten the sugar cube vaccine when I was in school. I'm 67 now. First of all, is that the same as the oral? Is that what you call on the oral vaccine? And should we consider-- in our age category, should we be thinking about getting vaccinated again?

Alan: If you got a sugar cube, you got the oral vaccine, the original Saban vaccine. As far as we know you're pretty much immune for life. This is actually both of these vaccines are very robust. They confer long-term immunity against disease. It's certainly the case that as people age, their immunity does wane against all sorts of things. You should ask your doctor about it.

If your doctor says, "Yes, you don't really need the booster," then I wouldn't go with it. There's very little evidence or really no evidence that I'm aware of in the literature of somebody who's in your situation aging out of immunity against polio after having been vaccinated, especially with the oral vaccine, which is extremely effective. I wouldn't worry about it too much, but the next time you're seeing your doctor, you might want to bring it up.

Brigid: Louise, thank you so much for calling. Alan, I'm just going to pause our conversation to do a little bit of housekeeping. This is our station ID. This is WNYC FM HD & AM New York, WNJT FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. This is New York and New Jersey public radio. I'm Brigid Bergen from the WNYC and Gothamist newsroom, filling in for Brian Lehrer. I am speaking with Alan Dove, a journalist, virologist, and co-host of This Week in Virology Podcast, I was told by my producers that people call it TWiV, not what I said before. Thank you so much, Alan, for being here. I want to get into a couple more questions related to what we're seeing now with some of the symptoms of polio and how severe outcomes-- how often are there severe outcomes, like paralysis or even death?

Alan: Right. I mentioned in the natural environment pre-vaccine, it was about a half of 1% or so of infections as far as we can tell, would result in some kind of a severe outcome. This could be paralysis of one leg, it could be paralysis from the waist down, it could be severe paralysis that led people to require respiratory assistance and that's where the iron lung came from when you see those old photos of rows and rows of people in iron lungs so that they can breathe properly.

Those outcomes while not common are, again, because the virus spreads so readily, they end up adding up to a lot of people. For example, in this case in Rockland County, we don't know if this is somebody who had traveled to a country where, or at least I haven't seen any information on this, whether this individual traveled to a country where the oral vaccine is in use, or if they picked it up from somebody who had traveled to such a country and then came back, or had been vaccinated elsewhere and then came to the US.

We don't know the exact chain of transmission. What happens is when the vaccination rate drops below a certain threshold, and it's actually a fairly high threshold, it's somewhere in the 90% range. You get enough people in the community and especially if they are clustered in groups of people who don't vaccinate, where you can sustain a chain of transmission of poliovirus. If enough people get infected, you will see more cases of people getting these severe outcomes, which even if you get something that okay, the partial paralysis in one limb, they may actually recover over a period of time.

This was a very common situation. People would develop a very bad case of polio, they'd be in an iron lung, and then they would recover to the point that they didn't need the iron lung anymore. Maybe they just needed crutches. Then late in life as their number of surplus neurons decreased essentially, the symptoms that they had had before could return. Even people who recover completely who had some degree of paralytic polio, some would make a complete recovery and then years later would have what's called post-polio syndrome, where they re-develop that same sort of paralysis. When poliomyelitis occurs, it is a lifelong condition.

Brigid: Alan, there was another story about live polio virus being found in wastewater in London, but no cases were found. Do US cities actually look for this?

Alan: I am not aware of it, although there's been a boom in interest in sewage testing for viruses, which as a virologist, I'm thrilled to see. I have been thinking for a long time, just from preliminary assays that people have done over the years, gosh, we really ought to be looking more closely at this. The pandemic really brought a focus on that because of the difficulty of testing large numbers of people individually, whereas you can take sewage samples and if you have a virus that shows up there, you can detect it.

I don't think it's routinely done in the US, but certainly, now that we are somewhat routinely in many places taking sewage samples to test for SARS-CoV-2, which causes COVID-19, I am hopeful that we'll start piggybacking other tests onto that. Poliovirus is going to be found in US sewage systems. Again, people travel back and forth and somebody goes someplace where the oral vaccine is still used or where poliovirus is still circulating. There are a couple of countries in the world where we still haven't quite knocked it out and they'll bring it back and because the injected vaccine that we use in this country does not prevent somebody from being a carrier, you could actually have a chain of transmission going on and it's possible.

This is what happened in Rockland County as well, where somebody gave it to somebody else who then gave it to somebody else and it just passed. Nobody knew it was circulating because everybody was vaccinated until it finally found an unvaccinated person and they had a bad outcome.

Brigid: It's so fascinating. We so appreciate all of your expertise. We're going to have to leave it there for today. My guest has been Alan Dove journalist, virologist, and co-host of This Week in Virology Podcast, TWIV. Thank you so much for joining us, Alan.

Alan: Thanks for having me. It's been good.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.