Hip Hop and Politics

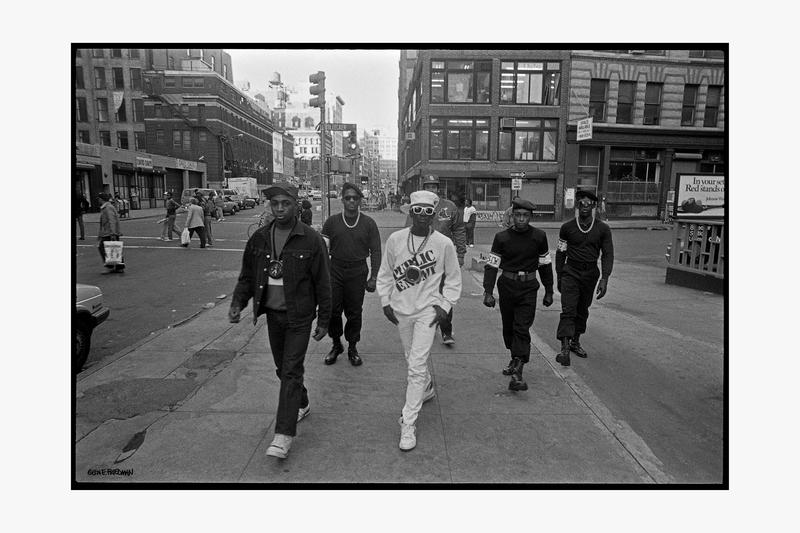

( Photo by Glen Friedman )

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

MUSIC - OutKast: Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik

Well it's the M-I crooked letter coming around the South

Rolling straight Hammers and Vogues in that old Southern slouch

Please, ain't nothing but incense in my atmosphere

Brian: It's The Brian Lehrer Show Music history special on this August 11, considered the 50th anniversary of the day, hip-hop was born in the Bronx. As we do some music, some conversation, some of your oral history calls 212-433-WNYC. Bringing us into this segment, there was the Atlanta-based duo OutKast wrapping some of their Southern pride in their 1994 classic Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik. Appropriately, with me now is Joycelyn Wilson, professor of Hip Hop Studies and Digital Media at Georgia Tech University.

Unlike some of the Bronx-born people we're all hearing from today, she was born in Alabama, grew up in Atlanta, and so brings a little different life experience to her scholarship, in addition to being a woman who studies what is often seen as a largely male art form. Professor Wilson, thanks for giving us some time today. Happy August 11 and welcome to WNYC.

Professor Wilson: Yes, hip-hop hooray. Thank you for having me. It's really exciting to be here and I enjoyed that introduction. Thank you.

Brian: Thank you. I enjoyed that little turn of phrase there. hip-hop hooray. We'll talk about the music, of course, and its place in American history and today, but would you introduce yourself a little to our listeners first? I see you grew up in a family of educators. What did they do and where was that for you mostly as a kid?

Professor Wilson: Yes. My mother is a retired school teacher, social studies and physical education teacher from the Atlanta Public Schools. I come from a family of educators, whether that's daycare centers or just keeping kids. I've been around women and them teaching and educating for a while. My family moved to Atlanta in the early '70s, along with the many African-Americans who were migrating to Atlanta during that time. I grew up in a very fortunate situation in the sense that I grew up around a lot of Black excellence. I grew up around civil rights legends and in the home of the civil rights, one of the biggest civil rights movements.

To be from and in a place that really saw hip-hop integrated with this in real-time has just been something to watch and to experience. I started collecting hip-hop early on and then realized when I became a math teacher myself, I started relying on some of the techniques that I saw my teachers using, and it was integrating music and integrating culture and pop culture into the classroom. After I read Tricia Rose's Black Noise as a first-year algebra teacher, high school algebra teacher, I said, "This is what I want to do. I want to bring my love for the culture, but also talk about it from a Southern perspective."

During that time, a lot of folks didn't really know a whole lot about OutKast or didn't think that OutKast was going to change the industry in the way that they did and the culture in the way that they did rather. I just started to think about ways in which I could get a PhD but focusing on hip-hop and its relationship with schooling and education. It's been a journey since.

Brian: We're going to talk about some of how you combined your background as a math teacher, of all things, with your interest in hip-hop and culture and politics but let me stay on your formative years a little bit first.

Professor Wilson: Sure.

Brian: Do you remember some of your earliest musical exposures? Was there music being played in your home?

Professor Wilson: Oh, of course, yes. My mother is an avid music collector. She had vinyl in the house, she and my dad. I remember when I was gifted my first twelve-inch, it was Rapper's Delight by the Sugarhill Gang. I had a portable turntable that I would take with me everywhere, whether it was to my grandmother's house, my dad's house, wherever I could go visiting family in Atlanta, I would take it. It was white, it was huge. It had this mural of the Bee Gees painted on the inside. I would take that along with my vinyl.

I got that from watching my mom collect records Ohio Players, James Brown, Jazz, I even know as far as Kenny Rogers, I have a pretty diverse experience with music and a love for music rock because of the exposure from my mom and just my love for it. I gravitated to music very early.

Brian: Do you have a basic approach to studying hip-hop as an academic pursuit?

Professor Wilson: Yes. I start with the lyrics. My PhD is in educational anthropology. A lot of people think I have a PhD in hip-hop and I don't. I'm an educational anthropologist. I have always started with the lyrics and looking at the lyrics and seeing what the stories are, and what they're telling and what questions can be generated from those lyrics. That love for looking at lyrics started as well. As a kid, I would go and go to magazine stands and literally go and look at, remember those magazines that would print the lyrics?

I would go and look at the lyrics and really just try to get behind what artists were saying. It didn't necessarily have to be rap music. I was just interested in the lyrics and the stories that were being told.

Brian: When you say educational anthropologist, what does that mean? People may have heard that phrase and think, "What is that an educational anthropologist?" Does that mean you study the way education is done in different cultures?

Professor Wilson: Well, I study the relationship between education and culture, and the ways in which different communities, communities of practice go about teaching and learning, whether that's inside the school, whether that's inside the home, whether that's through media. For me, I've done that mainly dealing with lyrics and music. That relationship, what can we learn, for example, in rap lyrics? I was interested in the language of schooling. I wanted to know more about what the hip-hop generation had to say about certain things related to education.

For example, what does this generation have to say about segregation or desegregation, or integration? What do they say about teachers? What does this generation have to say about knowledge and knowledge acquisition and the way in which it is acquired? Those were some of the early questions that I asked of much of the Southern Rap that was coming out during the time when I started this research and really focused in on it.

Brian: The Brian Lehrer Show Music History Special on this August 11th, considered the 50th anniversary of the day hip-hop was born in the Bronx. Listeners, once again, part of this Music History special today is some oral history from you. We are definitely inviting stories from some of you who may remember the early days of hip-hop in the 1970s. What was your first hip-hop experience? Tell us a story from the Bronx or southeast Queens or the southeast United States as we're hearing from our current guest, Joycelyn Wilson from Georgia Tech.

Anyone of any age, tell us a story of an important hip-hop moment for you at a concert, in community, or just privately, in your headphones, or whatever the story is, and how the music has influenced you artistically, spiritually, politically, any other way, listeners of any age. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Let's take another call right now with Professor Wilson, Moj in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC. Hello, Moj, thanks for calling in.

Moj: Hey, good morning. Thanks for taking my call. I love the conversation that's being had and just how much depth is being brought to it. Thank you so much for doing this segment. I just want to give a shout-out to my older brother, Mo. He introduced me to hip-hop back when I was 13 years old. He took me to Bed-Stuy and I saw Naughty by Nature and Salt-N-Pepa as my first concert ever. It was a formative experience, and I have my older brother to thank for that.

Brian: Any words you can put on that experience?

Moj: The energy, I'd never felt energy like that before. There was so much pride and joy, and it was a summer in New York City. That's a special feeling that we all know very well but so cool. I felt like I wasn't cool enough to be there, but it was just awesome.

Brian: I think you were cool enough to be there. Now, did you say your brother's name is Mo and your name is Moj?

Moj: Yes. His name is Mohammed and my name is Mojde.

Brian: I see.

Moj: Gets a little confusing at times.

Brian: That must have been tough for your parent. Mo, Moj, Mo, Moj. Did that happen a million times?

Moj: Yes.

Brian: Thank you for your call.

Moj: Thanks, Brian.

Brian: Thank you for your story. As we continue with Joycelyn Wilson, professor of Hip Hop Studies and Digital Media at Georgia Tech. I see on your Georgia Tech bio page, Professor Wilson, that your scholarship focuses on instruction in what you call STEAM. That's very interesting to me, and I think it will be to the listeners, because usually we hear the acronym STEM, for science, technology, engineering, and math. You said you were a math teacher earlier. You add the A for the arts, so it's STEAM.

I think the conventional categories would say the arts are in the humanities, which are almost the opposite of the math and science world. How do you see them fitting together in what you call steam?

Professor Wilson: Great question, because I think when we study hip-hop, we see that interaction. We see the intersection of the arts with technology and computer science and computing. We see it with mathematics. Hip-hop is a great case study for the ways in which we can understand innovation, and we can understand technology. The turntable, for example, is one great case study for the way in which it was used in order to extend the break beat. I think that a lot of us tend to separate the arts from the computational sciences, but really, they're more intersectional than we give them credit for.

When we think about the humanities, we oftentimes want to make sure that, for example, when we are teaching design thinking, or I teach courses in computational media, I want my students to understand that the things that they're making can have a humanity's impact or can impact human beings in real time. Trying to get them to understand that these are intersectional disciplines and not divergent disciplines is the reason why we put the A in there. I'm part of a project with a group coming up, a software called EarSketch, which is a software that uses music and making beats to teach students how to code and how to code in Python.

This use of the arts to teach the sciences is something that the research, particularly around education, has been moving towards for a while and bridging those together. I'm at an institute that understands that the arts, the humanities are very much a part of and necessary when talking about science, technology, engineering, and mathematics.

Brian: Really interesting. Now, we started the segment with music from Outkast because I know you've studied and written and spoken about them. That was a 1994 track, 21 years after the legendary party in the Bronx everyone is celebrating today, and they are an Atlanta-based hip-hop legendary duo, and you're Atlanta-based. Is there a moment, or Georgia-based, grew up in Atlanta, is there a moment when you'd say hip-hop first came to Atlanta?

Professor Wilson: Yes. Atlanta was always a part of listening to hip-hop. Like I said, Rapper's Delight was played on the radio stations in the south. When we talk about the history of hip-hop, for example, even just looking at today, August 11th, 1973, if we put that in context and try to understand what was actually happening socially and politically during that time, the party that who heard and Cindy through took place, I guess, Maynard Jackson was two months away from making history as Atlanta's youngest and first African-American mayor.

I think that we have to consider at the time that the practices and the elements were converging in New York and Atlanta, many of those social justice elements were forming with that election. Atlanta has always been a music city. It's always been a city for the arts. Auburn Avenue, bands like the SOS Band, Brick, Cameo, the Jack The Rapper Conference. By the time we get to Outkast, we have also had So So Def and Jermaine Dupri. We've had Kris Kross. There are these crumbs that get dropped or these building blocks, I should say, that led to that moment in 1994.

Atlanta always had this scene, even if we talk about 1982 when Planet Rock came out and the message came out, there was a song called Let Mo-Jo Handle It that came out in Atlanta. It's considered one of the first rap songs, and it was a song that was written for young folks in Atlanta who were just coming out of the sheltering in place season of the Atlanta child murders. There are these things that are happening in Atlanta alongside this party, alongside the early '80s that led to that moment in 1994.

Atlanta wasn't living in this vacuum at the time that these things were happening in New York. There were things simultaneously taking place in Atlanta that led to that 1994 moment without parents.

Brian: Is there what you would call in Atlanta, or more broadly, a Southern hip-hop sound, as compared to what we might hear typically in the Northeast, for example? You were talking about how growing up you listen to all kinds of music, including rock. Rock fans would think, "Oh, The Allman Brothers, that's like Southern rock and other bands like that." That's a different sound from, I don't know, Lou Reed, David Bowie you might hear in New York or British rock. Is there something you can put your finger on that makes a southern or Atlanta hip-hop sound?

Professor Wilson: Yes. There are three things I could point to. In Atlanta, hip-hop early on, particularly around DJs, was very much influenced by Miami Bass and the 808 very-- the BPMs are faster. You might hear it as bass or booty music. It's music that's going to get you to dance. By the time we get to Outkast, that music becomes very southern. You hear the country in it, you hear the punk, you hear the soul. By the time we get to trap music, we hear the trickling high hats. We hear heavy on the keys, particularly when we think about the music of Lil Jon.

He has influenced not just Southern rap, but just music in general, particularly hip-hop music, with the way in which he leans on the keys and creates these 808 drops along these trickling Hi-Hats. There is a particular sound that has now become a sound that has permeated outside of the south. It has become like its own blueprint or sonic blueprint for artists who don't necessarily live in the south. If we look at an artist like Drake, for instance. He is heavily influenced by Houston rap and the Houston sound, the Atlanta sound.

He was one of the first artists to jump on Migo's track. There are a lot of folks who are heavily influenced by that southern sound to the point where if you didn't know that Cardi B was from New York, especially on her first album, you'd think that she grew up in the south.

Brian: I think we've discovered that you're not the only math and science teacher in the world who also teaches hip-hop because we're having a call here who's ready to go. Angela, calling from Costa Rica. Angela, you're on WNC. Hello.

Angela: Hey, how are you doing, Brian? This is Angela. I retired, Brian, so I'm living in Costa Rica taking care of my mom. I was a middle school teacher in Bushwick, Brooklyn for 31 years, and I taught at the school I attended. I remember in 1977, when I was in fifth grade and going to-- she's from the south. People from New York would know the store, The Wiz, downtown Brooklyn. That's where you would go to buy all of your albums. I remember buying King Tim III and Rapper's Delight and bringing it into the school, the dance class, for the teacher to play.

I think because I grew up in that era when hip-hop first started, when I started as a middle school science teacher at the age of 22, I was able to relate to the students. I was telling your screener that every spring break, I would assign the students an assignment where they would have to either write a song or rap about anything or a poem, anything that we've done in science for the school year. I had one particular student, lovely young man, but just didn't feel like doing his work. He wasn't someone that was always on top of his work. When I gave that assignment, he and a friend of his, they would give up their lunchtime to practice to rehearse. His name is Jamutah. Jamutah and Tobi. They would give up their lunchtime to practice, to rehearse, to write the rap. They did a great job. I think that was the highest score, probably the only score because he was reluctant to do the work. He definitely, the both of them, put their time in when they had the opportunity to do their rap. I did that for my, I guess, almost 30 years of education.

I have videos of students rapping, I have VHS students rapping. It was great. I think they appreciate it. Some of the younger teachers saw that I did that, and then a couple of them would do that as well.

Brian: That is so cool.

Angela: Because that is definitely a form.

Brian: Writing poetry about science.

Angela: Right. Writing poetry about science. I would integrate all of the disciplines because students are talented in a variety of ways so I was trying to find an avenue for them to showcase what they've learned and to showcase their talent.

Brian: What a great story. Angela, thank you very much. Good luck with your mom down there. Thank you so much for calling in all the way from Costa Rica today. I want to play one more track here before you go, Professor Wilson, and you mentioned the band, the Migos. Of course, they've been in the news for the tragic shooting death of Takeoff at age 28, just last year. I guess you've already talked about the music a little bit, and Drake showing up for them. Anything else you want to add about that in context?

Professor Wilson: About the music or about Drake showing up for them in context? Nothing specifically about that. I think it was tragic that we lost him. Unfortunately, those are some of the valley that the industry and the community has had to deal with. Just rest in peace, Takeoff.

Brian: Before you go, we do have people writing in to ask about misogyny in hip-hop. Besides the inspiration and the fun and the empowerment of the music, and the social and political consciousness of the music, would you say as a woman studying hip-hop that there's also been a dark side that includes misogyny?

Professor Wilson: Sure. It's not unique to hip-hop. The misogyny against women is something that extends beyond rap music. I will say this, a lot of times, I'll get that particular question is usually followed up by how do I deal with it or how do I find the space to have a voice in what is considered largely a male-dominated field? I think that I like to turn that on its head a bit because oftentimes, we're conflating hip-hop with rap, and rap is only one element, one aspect, one practice, one form of expression of hip-hop. There are so many others.

I think where women have come in women are MCs, but women are also fashion designers. They're also stylists. We don't celebrate Cindy Campbell enough as the promoter of the party that we're celebrating today as hip-hop's genitives, or Sylvia Robinson or Tricia Rose, the first woman to publish a book and establish the field of hip-hop studies. I think what we have to do is elevate those moments where women are really behind the scenes, and they're pushing the culture and have push the culture forward from day one.

I find my motivation and my momentum in knowing those facts and that history, but also recognizing that there is misogyny and speaking to that when it's necessary. We talk about it in my courses, we try to get beyond just the surface of talking about it and think about ways in which women can empower themselves in these types of spaces. Because again, this extends beyond hip-hop. When you're using hip-hop as a teaching strategy, or integrating it into the curriculum, it's much larger than the integration.

It's designed to expose students to much larger critical forms of thinking, much more creative and enhancing their creative capacities or their computational capacities. I tend to focus on that part when finding my space and my voice in the music and speaking to the excessive misogyny when it's necessary, or turning it off. Because hip-hop is not new to the industry and the industry is push of certain maybe low vibrational things. One would think that it's excessively material because of the type of music that's being pushed.

If you go to, if you have streaming opportunities, you can dial a lot of the radio or dial a lot of some of the more traditional ways of hearing the music, and hear something that represents more holistically what the culture is about and what rap music is about.

Brian: Joycelyn Wilson, professor of Hip Hop Studies and Digital Media at Georgia Tech University. Thank you so much for joining us. I think our listeners really, really enjoyed it and so did I. Thank you.

Professor Wilson: Thank you so much for having me. I really appreciate it.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.