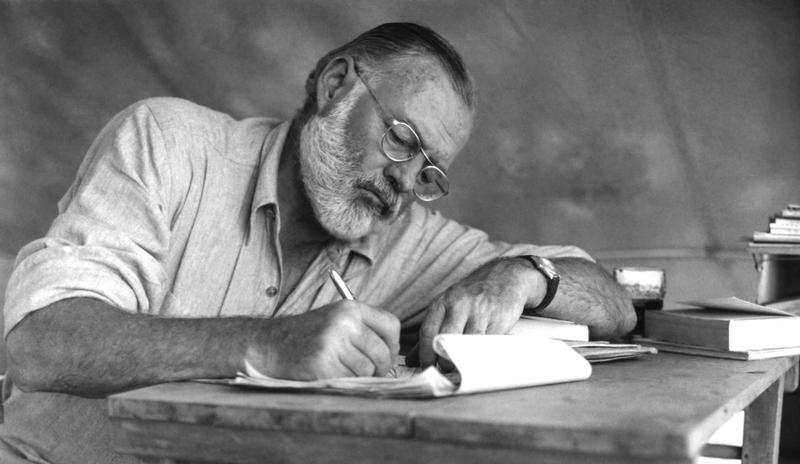

Hemingway, via Ken Burns and Lynn Novick

( Earl Theisen/Getty Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone we are always thrilled when Ken Burns and Lynn Novick come on the show. They're back today because of their new PBS documentary series on, of all people Ernest Hemingway. The hook is that this year, marks the 60th anniversary of Hemingway's death. He was born in 1900, died in '61.

The theme is to use Hemingway's work to look at the evolution of American ideas about masculinity. Joining me now to talk about their three-part six-hour documentary on Ernest Hemingway, are documentary filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novick. Hemingway premieres on April, fifth through seventh on PBS. Welcome back, Ken and Lynn, always a special day when you come on.

Ken Burns: Thank you, Brian. Great to be with you.

Lynn Novick: Thank you so much.

Brian Lehrer: Ken, you both have been wanting to cover Ernest Hemingway for years I see. Why Hemingway and why now?

Ken Burns: It's true, we've been thinking about it for almost 40 years about doing him. I think his outsized influence on American literature in the 20th century, and then I think a perception that our superficial understanding of him, of this kind of toxic masculinity, the big-game hunter which he was.

A deep-sea fisherman which he was, a brawler which he was, a drinker, all of that stuff, actually masked a much more interesting and dimensional character, who was able to bring into his work sympathies for women. Lots of other things that make that art, I think enduring despite some very tough pills to swallow along the way.

Brian Lehrer: Lynn, you've said that the way into understanding Hemingway is through his relationships with women. Let's talk about his relationship with his mother, to start out and his sister, Marcelline who was close to him in age. First, let's take a listen to a clip from your documentary, where we will hear biographer Mary Dearborn first, and then a reading of words that were spoken originally by Marcelline.

Mary Dearborn: She did this thing of twinning him with his sister. She dressed them alike. She dressed them in dresses often, but then she'd put them in overalls. She didn't only dress him up as a girl sometimes, she dressed the girls up as boys and there is this androgenic going on.

Marcelline: We wore our hair exactly the same in a square-cut dutch bob. We played with small China tea sets. We had dolls alike, and when Ernest was given a little air rifle, I had one too.

Brian Lehrer: Lynn, you want to talk about Ernest Hemingway's mother's influence on him including what that clip describes her androgynous approach to her son and her daughter?

File name: bl031121cpod.mp3

Lynn Novick: Yes sure. His mother was trained as an opera singer and a very dedicated musician. She actually gave music lessons and instilled in all her children her love of music and the arts. That's an important legacy that she gave him. She made him learn the cello. He sang in the church choir. He had developed a great affinity for the works of Bach, and fascination with counterpoint and repetition in Bach.

Those are dimensions of Hemingway that he got from his mother, absolutely. It was a household full of women actually. He had many sisters, just one brother. He and his father and his little brother were the only men in this very feminine environment actually. I think his sense of masculinity is developing in relation to that throughout his life.

His mother did dress him in dresses, and the sister in overalls but that wasn't so uncommon at the time. I think she kept it going till he was a bit older than was normal for his age. What we find is that throughout his life, for all his masculine posturing and persona and pursuits, he was very drawn to women. He was intimate with many women. He had four wives and all his sisters, and also interested in, “What are these gender roles that we are stuck into?” He was interested in pushing through those boundaries, which we found very surprising and interesting.

Brian Lehrer: You explore gender, you explore as you frequently do in your documentaries, race. For example, in one of his early works called Men Without Women, Hemingway uses the N-word multiple times. Let's listen to a clip from the documentary that includes an African-American history professor discussing this. We will hear two literary critics actually. First, Marc Dudley and then, Stephen Cushman.

Marc Dudley: Why use the N-word multiple times? Hemingway knows that it's probably one of the most offensive words he could have used even at this time. Could you make a case for Hemmingway being prejudicial in his life, in his writing? Absolutely, you could, but at the same time you could peel back the layers, and you can get a sense of a mantra trying to convey a sense of his time.

Stephen Cushman: That's not an excuse for him. I don't think you can dry-clean Hemingway into somebody, who fits into what we now consider socially and politically acceptable much at the time.

Brian Lehrer: Marc Dudley, who I believe teaches African-American literature at NC State, North Carolina State and literary critic, Stephen Cushman. Ken, can you talk about how you chose to handle a subject as iconic and problematic as Hemingway, in all these contradictions that you seem to be laying out?

Ken Burns: I think that's the way we've approached almost all the subjects we've tried to investigate, whether it's Lincoln's tardiness on slavery and emancipation, and the abhorrence thought that he still fought in April of 1861. That he could ship off African-Americans back to Africa, or Mexico, or South America, or some of the other figures we've done. Hemingway himself gives us direction.

He said it was important to include the bad and the ugly as well as what is beautiful,

because if it's only beautiful, you don't really get a full portrait. We took that to heart. Your listeners, I think will be reassured that PBS will blur offensive words and beep on the soundtrack, those same offensive words when they are spoken.

It's important if you're going to do a deep dive into Hemingway, and to begin to understand the contradictions that you [unintelligible 00:06:58] not conveniently ignore these difficult things, that I think give us all. A struggle of how to represent, and how to place in the context of what he was doing. He's using racist and anti-Semitic epithets and stereotypes in his work. It's disturbing, and we wanted as filmmakers to run towards that and not away from it.

Brian Lehrer: Lynn, the story as some of our listeners know has a tragic ending, because in his final years, Hemingway suffered from chronic alcoholism, traumatic brain injuries, and depression and he died from suicide at the age of 61 in 1961. The documentary tackles what you referred to as The Myth of Hemingway. What was it, and what do you think the way that the end of his life went should teach us about him or about life beyond him?

Lynn Novick: Well, the end of his life is seriously tragic and it is the culmination, but not inevitable of many forces lifelong or adult alcoholism for many years. A mood disorder of some sort, serious depression, suicidal ideation. His father had died by suicide, so that plants a seed but he was interested and fascinated by this question of suicide and what happens, how people end their lives from an early age.

He was exposed to a lot of death. He was fascinated with that existential question. He also suffered many head injuries which caused concussions, and potentially some brain damage and potentially a form of dementia. He was self-medicating with all kinds of drugs to help get through the day basically, by the end of his life. He became psychotically depressed and paranoid, and delusional and really, really seriously mentally ill.

At that time, the stigma and the taboo and the shame of that was such that-- I don't think it's clear that anyone even really discussed that with him in a serious way, that he was fully aware of all the things that were going on. He knew he wasn't well, but he wasn't in control of himself. Just seeing this unraveling and disintegration of this great artist, complicated man, is really tragic.

It didn't have to end that way, but given his fame also-- One of the commentators in the film says that the people, who get the worst medical care, are the poor and the very privileged, especially famous people. Doctors are intimidated by them, want to be friends with them, let them get away with things, and that is certainly what happened with Hemingway. He didn't get the best medical care at that time for his illnesses. That's the way it ended. It's really, really, really sad.

Brian Lehrer: As accorded to this segment, Ken, our next guest will be Jordan Klepper from The Daily Show. I want to play you a very short clip of Congressman Adam Schiff from a comedy interview with Jordan Klepper. Klepper asked Schiff how he would compare the second Trump impeachment to the first one, the one that

File name: bl031121cpod.mp3

Schiff led on Ukraine, if he was comparing them to movies. Here's what Adam Schiff said.

Adam Schiff: Ours might've been more the Ken Burns documentary. This might be more of the HBO miniseries, but we had to try to bring to life events that were happening half-a-world away in Ukraine.

Brian Lehrer: Tell Adam Schiff and Jordan Klepper, did you ever think of the first Trump impeachment as a Ken burns documentary?

Ken Burns: That's a question that God willing, Brian, 25, 30 years from now, you can be talking to Lynn and me about. I think the great gift of Hemingway is that it is so outsized, that all of the problems and it is a cautionary gift, of course as Lynn has described perfectly. He's given us some great arts, some great stories that get under the skin of women as the writer Edna O'Brien says, and speaks to that androgyny and does things that belie that macho image, including the gender fluidity.

I think with all the problems, they're so outsized that they become a gift for us because we learn to recognize them, and then realize that our own selves are smaller, less-loud versions of this and there might be something healing that comes. Something transformative that comes not just from his art, which is enduring and transformative, but also from the foibles of his life, the pitfalls of his life, the distractions of all of these things, and of course the Shakespearean tragedy of the last decade of his life.

Brian Lehrer: The three-part six-hour documentary titled Hemingway premiers on April, fifth through seventh on PBS. If you want to hear more from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, they will be at a virtual event tonight called Hemingway Gender and Identity that's at seven o'clock tonight. You can register for that online at pbs.org/hemingwayevents for that Ken Burns, Lynn Novick virtual event tonight at 7:00. Thanks so much for coming on. It's always great to have the two of you.

Ken Burns: Thank you.

Lynn Novick: Thank you so much, Brian. Great to be with you.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.