Grading Mayor Adams on Public Safety, So Far

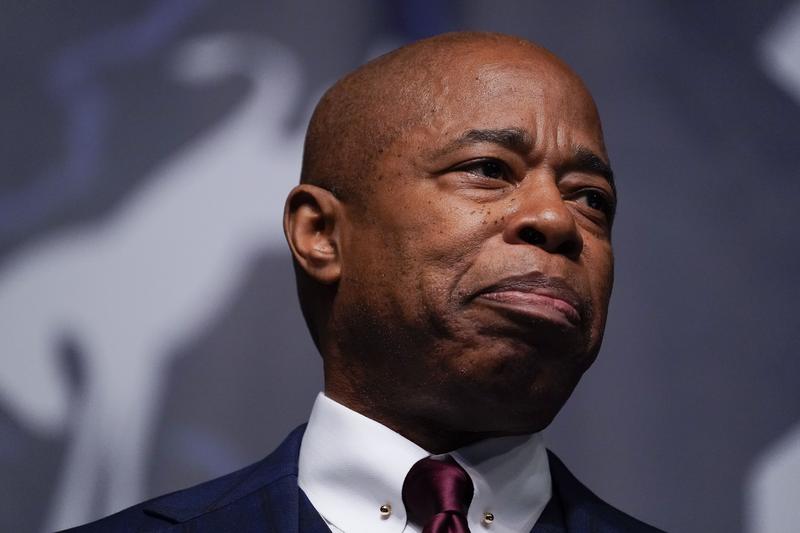

( Seth Wenig / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We will begin with a little breaking news that just came out a few minutes ago that will be of particular interest to parents of two to four-year-olds in New York City. This is a statement on mask requirements from the mayor's office. It says, "New York City Mayor Eric Adams today released the following statement regarding mask mandates in schools and daycare centers for two to four-year-olds." The statement says, "It's now been two weeks since we removed the mass mandate for K through 12 public school children and our percent positivity in schools has thankfully remained low.

Each day we review the data and if we continue to see low levels of risk, then on Monday, April 4th, we will make masks optional for two to four-year-old children in schools and daycare settings." The mayor says, "This will allow us sufficient time," that is waiting until April 4th, "to evaluate the numbers and make sound decisions for our youngest New Yorkers. We must get this right for the health of our kids. I refuse to jeopardize their safety by rushing a decision." There you go. That's our first bit of news today, right out of the box. Errol Louis is here, the widely respected host of Inside City Hall on NY1 and New York Magazine columnist.

We'll talk about the two to four-year-old mask requirement and the pandemic. Errol's latest for New York Magazine caught our attention because it flips the script on the usual debate about Mayor Eric Adams. It's usually Adams anti-crime policies like a new anti-gun unit on the streets and giving judges more discretion to lock people up before they're convicted of anything. Taking us backwards on social justice in the name of public safety. That's the usual debate. Errol's column flips the script with the headline, "Eric Adams Isn't Off to a Great Start on Public Safety. The new mayor needs to focus more on substance than show." Errol, always great to have you on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Errol Louis: Great to be with you, Brian, good to hear your voice.

Brian Lehrer: Before we get into the mayor and public safety, you want to give us a quick reaction to this announcement on two to four-year-olds and the masking requirements that might come off on April 4?

Errol Louis: Well, yes, might is the word, I think, because when they say April 4th, that gives us a couple of weeks to see the positivity rate increase, which I think is almost a certainty. Not necessarily in the schools, but in the larger city, I think we're already starting to see the numbers tick up. The health commissioners that I interviewed suggested that we should be prepared for that. I don't think anybody would be all that surprised. You see how abruptly people dropped masking, in general, in lots of different venues, restaurants, and sports arenas, and on and on and on. Anecdotally, I can tell you, I know a number of people who have tested positive in the last couple of weeks.

I think that will probably continue. I think the mayor is moving that discussion a few weeks forward. When that date rolls around, when early April rolls around, I think we're going to have to fight all over again about what should be done with kids who are too young to be vaccinated.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, that's really interesting. I guess this is because of the Omicron version 2 that's starting to circulate. We know it's spiking a bit in Europe. Usually, what happens over there happens over here just a few weeks later. As you said, it's starting already, but in a pretty minor way so far to happen here. Are you suggesting that the mayor put out the statement on unmasking two to four-year-olds potentially on April 4th because he's setting us up to hear that, "Sorry, this is still required," at that time, rather than just saying it's still required now?

Errol Louis: Something like that. Yes. I think that's a very likely outcome. Let's put it that way. I believe that there were a number of public officials. Look, to be fair about it, they're saying one thing. They're saying we're always going to be guided by the science. The reality, especially in an election year, is that we know that the governor and others are going to be affected by a large amount of public input. As they should be, they're elected officials. The public has said they're sick of this, they want these mandates lifted. They don't see why you would use a cut-off for five years old on and on and on. There's lots of different political pressures on them.

More and more, we're seeing elected officials responding to that pressure. I would put today's announcement in that category. However, I think, as I said it, it sets us up to have the conversation all over again. What are you going to do when you see a bunch of breakthrough cases among teachers and staff or in neighborhoods in general? What will that mean and what will we do? That's the question now, and I think it's not necessarily going to look all that different on April 4th.

Brian Lehrer: Since we got onto this topic, I'll ask you one more question that's related. I don't know if you've reported on this either in your New York Magazine column, or on Inside City Hall in NY1, but there seems to be a vaccine requirement that's unique in New York City that's starting to make headlines because of its relationship to the coming Major League Baseball season, which begins that same week later the week of April 4th. That is that the Mets and Yankees when they play home games, would not be able to participate in home games if they're not vaccinated.

The Daily News Columnist Mike Lupica was on the show the other day and said, what he's hearing is that as many as half of the Mets might not be vaccinated. New York City is the only place left in the country, I believe, that has this vaccine requirement for all employees of private businesses, which is why the baseball players are covered. Of course, a lot of other people who aren't baseball players covered vaccine requirement for all people going in person to work at private businesses in New York. I think it's unique in the country at this point. Do you know if this has become a source of debate on that uniqueness?

Errol Louis: It's going to be a source of debate because it's a source of confusion. I know you're a huge baseball fan. I'm on the other side of the river watching my Brooklyn Nets deal with the frustration and confusion and contradictions of a star player Kyrie Irving not being able to play home games so that he goes on the road and scores 60 points in a night. It's serious, and they got fined because he went from being a spectator in his own home arena, where he's not allowed to play, and he walked into the locker room, which is now considered the workplace. That then triggered an NBA fine. It doesn't make sense. It's not logical.

I think what the city is doing, though, by maintaining these requirements for workplaces-- There's a certain logic to it. If you move yourself out of the fairly unusual workplace, your workplace happens to be the Barclays Center or Yankee Stadium, or Citi Field. If you make it a small lounge, a small restaurant where workers have to come in contact with all kinds of people all the time. Yes, you want to protect the health and safety of people who, after all, they're just trying to make a living. The city is in this odd, contradictory place. I think you are going to find that an amazing number of these millionaires who play sports have decided not to get vaccinated.

They think they're invulnerable, their bodies do whatever they tell them to. Whatever reason it is. They don't want to tamper with what they think is a finely tuned tool, which, after all, is their source of income. I think we're going to have a mayor and a governor who are going to have to straighten this out, and at least make it logical so that visiting teams don't have more rights than the people who actually work in the building.

Brian Lehrer: Then I don't want to continue to go down this path too much further. There would be an argument to go further the other way and keep the mandate on the customers in the smaller venues like restaurants and stores. If you're going to protect the workers like Mayor Bloomberg, no smoking policy was a workplace safety measure for the people who work in restaurants. It couldn't be just the waitstaff and the kitchen staff who isn't smoking, it needed to be the customers. If you're going to protect those workers, you should really keep the vaccine mandate on the customers too but they certainly are not there at this moment.

Errol Louis: No, no, no. Here again, look, governing is tough, right. We have an economy that needs to recover. Hospitality and nightlife are the leading edge of that for a lot of people. For a lot of working-class families. We need to get that stuff up and going. I mask when I go into restaurants. I'm acting as if the restrictions that were lifted in the last few weeks basically never happen. I'd double mask in the Uber, I wear a mask around my newsroom. I wear a mask in restaurants, and I just don't see any particular reason to. I think we are migrating towards that, Where individuals will have to make choices.

Unfortunately, that doesn't amount to a public policy, but I think that's going to be the de facto outcome when the smoke settles.

Brian Lehrer: All right, let's talk about these other kinds of public safety. We'll get into the specific

` policy areas that you write about in your New York Magazine column like more NYPD chiefs on patrol in the subways and the prison-to-shelter pipeline-- or really jail Rikers Island to shelter pipeline. As an overview, Adams hasn't even been in office three months. Whatever his policies are, are barely taking effect. To your headline "Eric Adams Isn't Off to a Great Start on Public Safety," how do we begin to judge?

Errol Louis: Well, look, first of all, when it comes to the planning of a policy before it gets launched, he had in effect arguably six months before he was sworn in on January 1st to get some of these things together. I actually wrote about this. I think he burned up some of his honeymoon time just because of the unusual new political calendar that effectively concluded the race for mayor back in June. November was kind of a formality. Then also, look, 100 days on something as urgent as public safety. First of all, 100 days is decent, I think, and reasonable marker.

Even if it wasn't, Brian, the Mayor himself on an almost daily basis, there might have been a few days that he missed out on this, but every day he says, "Public safety is the issue. The urgency can't be overstated. I am going to deal with it." He says that every single day. In fact, one of the things I mentioned in the column is that he's the one who keeps doubling and tripling down on this. Whereas he always has the option of saying, "We're going to deal with this. It took us two years to get into this mess. It's going to take a little time to get out of it. I've got some policies that I think are going to work and that's why you elected me."

He doesn't do that. He says, "We're going to deal with it right now. Today, right now." "Promises made, promises kept," I think he said at one press conference. Fine, we'll take him at his word. I would've accepted almost any timeframe that the new administration said would be a reasonable period in which to judge them. My sense is that the Mayor has told us all to expect results almost immediately. I don't know how realistic that is.

Brian Lehrer: You're right, for example, about the highest levels of assault and homicide in the subways in 25 years, and turning that around can't simply be a matter of enforcing the MTA's rules of conduct like turnstile jumping or sleeping on the trains. Is that all Adams has been focusing on in the subways?

Errol Louis: It's odd because when the Mayor rolled out the subway safety plan, and even to this day when he talks about it, there are two problems that are going on and he sometimes speaks about one as if it were amenable to the solutions that are developed for the other. By that I mean, look, you have a lot of disorderly people. They don't have any psychiatric problems. They don't have any particular low-income problems. They're just down there acting out the way some people sometimes do. Perhaps they're drunk, but they jump the turnstile, they start fights. They eat food, they make a mess. They get into problems with other people. They make it unpleasant for other passengers.

They decide to pull out a joint or a cigarette and smoke on the train. That happens. That's one level of disorder and that can in fact be addressed by sending more cops down there, which is what the Mayor has done. Then there's this other much more difficult category. That's the one that makes the big headlines. That's the one that involves multiple different problems, multiple different sectors of city government that are not acting in a coordinated fashion. That's people who are in encampments. That's people who are clearly seriously mentally ill. That's people who are battling addiction. That's people who are off their meds.

That's people who are homeless, unhoused, and afraid to use the shelters because the shelters are dangerous. That's a tangle of problems that you've got to deal with. That's something you're not going to deal with by sending a squad of officers with guns into the subway. There are strategies for that, but those strategies are much less prominent. They don't work as quickly. They're a little bit harder to measure. Frankly, I don't know if we've gotten a lot of good information out of the administration about how that much more difficult effort is going. Of course, we have a fed-up public that just wants the whole thing to vanish. That's the one thing we know is not going to happen, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: The Mayor has ordered chiefs, which, for people who don't know the NYPD, are the highest-ranking officers still in uniform, the chiefs, to regularly walk a beat in the subways, but that is a topic of derision. You say "disgust" in your article in the upper ranks of the NYPD. Why is that?

Errol Louis: Look, a chief is a very, as you described, it's a very high rank. It's someone who might be in charge of half a borough and 1 of the major patrol boroughs, 5 precincts, 10 precincts. That's somebody who is overseeing crime and strategy and making strategy and bearing responsibility for the outcomes of strategy across half of Queens or half of Brooklyn. To have a person like that walk a beat underground where they have to-- if they're going continue with their actual duties, they're going to have cops upstairs monitoring radios. God forbid something should happen.

Something could be a shooting, that something could be an unusual occurrence of some demonstration that breaks out, or ultimately it could be even a terrorist attack or fears of a terrorist attack. To have the person in charge walking a beat on the platform according to these chiefs, they say, is a monumental waste of time that actually could impact public safety. Former Commissioner Bratton weighed in, and he's been nothing but supportive of the administration up now, and he said, "Listen, it takes specialized training to be able to walk a beat effectively underground."

You have to know how to evacuate a train. You have to know how to open a door in an emergency. Smoke conditions, communications issues. It's not just walking down there and waiting for somebody to hop a turn stop. All of those issues for a lot of the professionals are a way for them to also-- Look, cops complain about everything, honestly, but one thing that they do complain about they say like, "Look, this is nuts. This is not a game for us. This is not a dog and pony show." It's nice for him to be able to dip into one form of management literature and say, "Hey, generals have to lead from the front. Get out there and patrol the subways."

It's like, logistically, technically, as far as training, as far as actually making sure the city is properly covered. These are major considerations. They're a little angry that they're being trotted out to do something that they don't think is all that important in the first place.

Brian Lehrer: Besides the anger of the NYPD members themselves to the subhead of your New York Magazine column "The new Mayor needs to focus more on substance than show," do you think having these chiefs who in their real jobs are in charge of half of each borough as you say walking beats in the subway, do you think that's just a performative policy on the part of the mayor?

Errol Louis: Oh, yes, no question about it. Look, somebody will ask him at some point, "What have you learned? What have your chiefs learned? What's been the outcome of this new order that you gave them? What insights are they gleaning from walking up and down a subway platform as opposed to sitting in a command center?" We'll see. I'd be very surprised if they picked up some insight that they weren't already aware of because they all have what are called the executive officers, who's really like your hands on the ground, and they've all got sergeants and--

Look, there's a chain of command. Any chief who thought there was a problem in any given sector is absolutely free to go over there and poke around and see what's doing. Being told that you must get out there and patrol and give up a shift or half of your shift. To do this is I think what some of them found baffling and annoying and probably more political than what they wanted. They've already got their hands full. Cops, especially at that level, they feel a great deal of responsibility. Probably more than most people realize. Just like the political class, they feel like they have to answer, that they've got to produce for the city.

They cry too at some of these tragic stories of people getting hurt or killed. They want to be able to do this, and they want to be able to do their jobs without a lot of political interference, which is what some of this is seen as.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we can take your phone calls for Errol Louis, the host of Inside City Hall weeknights at 7:00 on Spectrum News NY1 and New York Magazine columnist, talking about, well, these various kinds of public safety. There's the Mayor's announcement in the last hour that we read with, that he's considering removing the mask mandate for two to four year old's in the city preschools and in the daycare centers despite the fact that they can't be vaccinated. He might remove that on Monday April 4th if things continue to go in the right direction.

Errol commenting that that may be a reaction to public pressure to do that even though the Omicron version two seems to be increasing in the city right now, and that the mayor held out the prospect of relieving the mask mandate on April 4th, rather than just doing it now to give us a couple of more weeks, during which time he may have reason to say, "Look, things are going up again. It is not time to do this," but he will at least have addressed the question and the pressure to address it that's coming from a lot of parents. We can talk about that.

Certainly, we can talk about public safety in the form of violent crime and the mayor's early responses to that, Errol's New York Magazine column "Eric Adams Isn't Off to a Great Start on Public Safety" is the headline. "The new mayor needs to focus more on substance than show." What do you think, or what question do you want to ask? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Errol, you remind us that many people who sleep on the trains do so because they're afraid of violence in the shelter system. You suggest some of that may be from the number of people the city releases directly from Rikers Island into the shelter system. How many, and why so many?

Errol Louis: Well, not Rikers, Brian. I'm not talking about the prison system. I'm talking about people who have served years in prison.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, you were talking about the prison system, when they come out of actual sentences for crimes they've actually been convicted of that were worthy of prison time.

Errol Louis: Yes, exactly right. By definition, at least a year. A couple of years ago, the numbers were, I believe, from 2017-2018, my colleague Courtney Gross, did a story, did an investigation, and found that 54% of people, all people coming out of prison were ending up in New York City shelters.

That's a matter of in order to get released, you have to give an address of where you're going to go. If your family doesn't want you or your family is not available, your family's not around, if you don't have any other options, if you don't own property, or have an apartment leased somehow, which frankly, not a lot of people are apartment hunting while they're serving two to four years of prison, they send you to the place of last resort, and in a lot of cases, that's a New York City shelter.

Frankly, what ends up happening, and this is what people are advocates are saying it, some of the unhoused themselves are saying it is that these folks are creating a dangerous situation, that they're preying in some cases on people who were very, very vulnerable, who may have a serious mental illness, but have some kind of resources or something worth taking. People say, "I'll take my chances on the street. It may not be comfortable on this subway train or this street corner, and I might even get robbed, but I know I'm definitely going to get robbed if I go into that shelter." That's the kind of mess that we're dealing with.

That's why I think some of the pronouncements from the administration, about their good intentions, are not going to solve some of these thorny problems because think about what I just described, you've got to talk now to the state prison system, ask them what the heck they're doing with their reentry programs. You've got to deal with a whole bureaucracy with the Department of Homeless Services. You've got to talk to the MTA that some of these folks are ending up on the trains. You've got to deal with some of the private providers who are supposed to provide assistance to some of these vulnerable New Yorkers, and then you've got the cops.

You've got a really complicated problem down there. It's not as easy as saying, "Hey, get those homeless people off the train," you've got to try and work through this stuff. That's what I fear is not going to happen as quickly, as many New Yorkers would like to see happen.

Brian Lehrer: This ties into another of your recent New York Magazine columns called "New York's homelessness crisis needs more than this. Addressing subway violence requires a major investment in social infrastructure." You compare funding to address that, two items getting most of the attention now in the current city and state budget proposals. They're both in budget season for the next fiscal year, and your site things like universal childcare, tuition-free CUNY for city residents, and helping people with delinquent utility bills, which of course, have been part of the inflationary spiral recently, but you almost dismissed those things to my eye, Errol, by calling them "interesting and worthy proposals," but compared to what you call the emergency underground, that requires a dramatic increase in funding. Are the budget lines not there at the city or state levels in your opinion?

Errol Louis: Now the budget lines are there. Look, where that came from, Brian, was it just so happened on the same night. Early in my broadcast, we talked about the breaking news that night that the governor has proposed polls paying $500 million worth of delinquent utility bills on behalf of apartment and homeowners, at least that's the way it was described. From another point of view, that's like just a big subsidy to Con Edison and some of the other utility companies. That was to the tune of $500 million.

Later that same night, I talked to the head of The Coalition for Behavioral Health, or an alliance of over 100 of the nonprofit providers that deal with seriously mentally ill people, with addiction treatment, with homelessness and so forth. They said they had put it a quest to the state for $500 million to deal with a staffing shortage, to deal with the additional workload that they have for all the reasons we were just describing in the subways and elsewhere, and they got turned down.

I'm thinking to myself, "These are misplaced priorities." This is the period during which there are public hearings, and the legislators are supposed to hear from the public. So I said, "Well, you know what? They should hear from me, they should hear from more of us. We should tell them that." I understand that we're only about 100 days away from the primary and everybody's got their eye on their own reelection, but we have a serious problem here, and for once, we actually have enough money so that people can say, "Hey, how about a billion for this? How about $500 billion for that?"

Well, put $500 billion toward serving the state by dealing with this very, very serious set of problems, and next year, when the money's gone, the answer will be, "Well, we don't have enough money." Now would be a really good time to try and address this tangle of problems that we all walk around and see every single day and have a right to deserve some action from a legislature that for once has enough money.

Brian Lehrer: We'll continue in a minute with Errol Louis. We'll start taking your calls, also your tweets. I see some people are tweeting questions for Errol @BrianLehrer. Stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC with Errol Louis from New York Magazine and NY1, talking about public safety from COVID to street crime. Here's a question via Twitter from a listener, Errol. It says, "Brian, why does not the system provide police protection in the shelters to make them safe?"

Errol Louis: That's a great question. The short answer is they do. There's something called DHS police. Once in a while, if you're looking for it, you'll see that they actually put out recruitment posters, they have a little Academy, they put the people through some training, and then they assign them to different shelters, but questions must be asked. You have to keep in mind, somebody who comes to a shelter, they're not in custody, that was not a jail. If they feel like getting up at two o'clock in the morning and going for a walk, there's nothing to stop them. If they bring contraband, if they bring drugs into the place, if they are engaged in other kinds of activity, there's not any particularly tight way to control that.

It's a very tricky kind of a proposition to try and catch or head off or prevent anything short of actual outright violence. That is, I think, where the problems start to fester. The answer is, yes. We the taxpayers are paying for something called the DHS police. What kind of a job are they doing? Well, more questions probably need to be asked. We've certainly seen it documented that people feel that there's enough drug use and intimidation and violence in the places that they actually won't stay in those buildings, which raises the question of, what are those DHS police doing, and how can we help them do a better job?

Brian Lehrer: AJ in Manhattan, you're on WNYC. Hi, AJ.

AJ: Hi, Brian, long-time listener. Thank you for taking my call. I live in Stuyvesant Town, which for those of your listeners who don't know, of Stuyvesant Town-Peter Cooper Village runs from First Avenue to Avenue C and 14th Street to 23rd Street, and we have a situation that's been going on here since the pandemic of illegal panhandling on 14th Street along First Avenue and from First Avenue to Avenue A. We cannot get anybody to help us with this.

The strange thing about 14th Street is that the South Side is controlled or overseen by the 9th Police Precinct and the north side is controlled by the 13th Police Precinct. This activity is taking place on the South Side, which, again, the 9th Precinct's domain. We cannot get Council Member Carlina Rivera or the 9th to deal with this. We have dozens of illegal vendors there every day trashing the street. People do not feel safe walking around there.

Brian Lehrer: AJ, let me ask you to separate the things that you're bringing up a little bit because panhandling is one thing, it's asking people for money, then illegally, is one thing, that's selling stuff on the street in front of stores. Being afraid of violence on the street is another thing. Are you relating the two?

AJ: We don't feel safe walking down that part of the street. Many of us just do not feel safe. This has been going on for a couple of years, as I said, and we cannot get anybody. The police have come in once or twice and removed everybody. Within hours, they're all back again. We have no sustained effort here to get rid of what's going on here so that we can feel comfortable walking on our streets.

Brian Lehrer: AJ, thank you very much. Errol, my reaction to that call is a little bit like, maybe the caller's conflating things, but maybe there's a relationship, at least politically here. If they're not enforcing who's allowed to vend where, if they're not enforcing panhandling, as she put it, that that has a relationship to potential violent crime on the streets and not feeling safe. Those do get all thrown into a bucket in the political sector, but also they're different.

Errol Louis: Yes, that's right. It's really site by site. You're old enough to remember, Brian, when they had vendors all along 125th Street, and there was a big cleanup effort. This was in the Dinkins administration, in part because the drug sellers, the narcotics illegal drug sellers, were using it as camouflage. They'd be mixed in among the vendors, and they were doing all kinds of other stuff. The same thing happened in Bed-Stuy on Fulton Street, where they had to do a big cleanup. It's tedious work. You have to involve lots of different groups.

There are legitimate vendors, in some cases. If anybody's out there selling books or other material, that's protected under the First Amendment. You don't need a license or any permission to sit on the sidewalk with a bunch of pamphlets or books and try and sell them. You have different categories of vendors. It gets very complicated very quickly, actually.

I suspect that because you identify the exact area, and the precinct, and the relevant political leadership, you may get more of a response now that WNYC listeners are hearing this, but it's tough.

Then the old standby, not to say that that's necessarily the case here is that when you're at these boundaries between precincts, in some cases, what the precinct commander will tell you is like, "Look, we've got huge problems at the other end of the precinct. A bunch of guys who are a nuisance at one end, if there's no actual violence, then we're going to maybe prioritize that at a lower level," which I know is very frustrating for a lot of New Yorkers, but that does often happen as well.

Brian Lehrer: Drew in White Plains, you're on WNYC with Errol Louis. Hi, Drew.

Drew: Hi. No. It's actually Drew calling from White Plains. Hey, Errol, I'm a real big fan. Two things I wanted to bring up, Errol, I really admire your career. I was born and raised in Harlem, but I've been up in Westchester for about six years. I live over here in White Plains, and you're from the neighboring town, New Rochelle, which is a great thing. I think the thing that kills me the most, Errol, about last year's elections is everybody talks about this red wave that hit, and they talk about the suburbs, but they leave out Westchester County, and how it became a graveyard for Republicans.

Not only are they elected Democrats in Westchester County, but if you look at the congressional seats, they're electing Black Democrats that are more to the left, whether it's Mondaire Jones or Jamaal Bowman. Mondaire Jones is actually a little bit more moderate. I don't even know why people call him a lefty because if you look at his positions and the stances, he's a little bit more moderate. What I was saying was with these positions that Hochul is taking, playing footsies on the bill reform, do you think that Jumaanecould possibly upset her because I think people think that the suburbs are this moderate place where there's swing voters. Even Lee Zeldin talks like that.

I don't think people realize Westchester County has turned into New York City. We have a 16, 2-county legislator run by Democrats and on a red wave this year the incumbent George Latimer, he beat his opponent by 24%. That's the largest margin of victory ever in the county executive race. I definitely think Lee Zeldin is dead on arrival. I think people are playing this election up.

Brian Lehrer: That's Lee Zeldin the likely Republican nominee for governor. I want to anoint Drew our new Westchester bureau chief for all that political analysis, Errol, but what's your take?

Errol Louis: I love it. Thank you, Drew. Look, it's a small subset of us who really love Westchester politics and follow it closely. I got a lot of family up there and yes, I think he's right. Look, there's a place for Democrats in Jumaane Williams as a candidate or anybody else. If you're on the progressive side of the fence, there are places where you can pick up votes. You go to New Rochelle, you go to Mount Vernon, you go to Port Chester, you go to White Plains, and you pick up 100 votes here and 200 votes there, the next thing you know you can get something going. George Latimer is definitely an example of that.

Another interesting example, Drew, I just saw Alessandra Biaggi put out a video that is caught on social media this morning. There's this new political district that Tom Suozzi is departing as the incumbent. The lines have been redrawn to include a little slice of a piece of New Rochelle and Pelham, and that's where Alessandra Biaggi is to face. She's a progressive legislator. She's giving up her state seat to run for Congress. It's going to put to the test exactly what you were talking about, how progressive is Westchester?

It's a small slice, I think it's only about 16% of what is a mostly Nassau County District, but there's a little piece of the Bronx in there. We'll see if you can put it together. The politics is changing. What we call suburban politics, everybody should know if nothing else that Westchester, especially lower Westchester is very different from Long Island, different issues, different style, different flavor, different ethnic makeup, and more and more, they're voting very differently.

Brian Lehrer: Drew, you'll be happy to know, by the way, because this doesn't happen very often, that even before you finished your first comment, we got a tweet from another listener who wrote, "This caller from White Plains is on fire," with fire being represented by four fire emojis. There you go.

Drew: [laughs] Thank you. Thank you, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Call us again, all right?

Drew: All right.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. Now, by way of contrast, Errol, here's another tweet that came in, it says, "Please discuss the factors that got us here," speaking of violent crime. "Why has it gotten this bad so quickly? I don't accept this is just about COVID, we had 25 years of prosperity and a safe city, this has to be a result in part to the lack of consequences for criminals," writes listener Gloria.

Errol Louis: Yes. I don't think that's true. It's simply not true. I've talked to everybody I could possibly find to answer that very question. The reality is, in places like Chicago, in places like Los Angeles, in places like Houston, the cities where they had no reforms whatsoever, and where, believe me, there are very serious consequences. You go to Houston and commit a violent crime, if they catch you, you are going to really pay the price, and crime is spiking in all of these areas. I would not write off COVID, and there's no particular reason to.

Think about the trauma that happened in New York, just as a general proposition, like how grim it was. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers lost in a matter of weeks. That in itself is traumatic. Well, let me give you something else. This is a theory that I heard talked about at the height of the pandemic. We still don't have any solid numbers on it, but I think it's an area that we should definitely look at.

There are a lot of households in low-income communities that are basically run by the grandmother, the grandparents. They're missing a generation. Somebody went to prison or some other thing happened. Well, we know the elderly were the first and most targeted casualties of COVID. There are a lot of grandmothers who just vanished, who died, who were hospitalized, who were on ventilators, and the households that they were holding together began to disintegrate.

I think that's a very plausible scenario, at least in the neighborhoods that I'm familiar with and where I live, for how you could get a surprisingly high amount of disorganization in a handful of families. Keep in mind, all it takes is a couple of disruptive individuals to turn a community or a neighborhood upside down. If you have newly orphaned people who are in a really difficult situation, and who may even be old enough that they're emancipated, that there is no particular help for them from the social service sector, I would be very curious as to whether or not that's what's driving some of the disorder.

The short answer is, and this is something I know nobody likes to hear, but I think we have to have some humility about this and accept what the experts tell us, we don't know why this is happening. To be honest with you, from coast to coast, if you're seeing simultaneous spikes in crime in areas that had bail reform and areas that don't have bail reform, in areas that have a serious addiction problem, and overdose deaths, in areas that don't have those overdose deaths, crimes going up everywhere.

This is across the globe to a certain extent. Why is it happening? We don't know, and because we don't know, we have to be, I think, a little bit cautious about trying to fashion a response. I understand there are politicians, including the Mayor, in whose interest it is to say, "We got this, we know what to do," but the reality is they don't necessarily know with as much certainty as they might be portraying, and we should all keep that in mind as we try to figure our way out of this.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. As we wrap up, I think this is why I most appreciate these last couple of columns of yours, in New York Magazine, on the crime rates in general and on the subway crime, in particular, and its relationship to homelessness because so much of the conversation in the media is about the bail reform. I think it's being driven by the politicians who latch on to that one side or the other of that and then that becomes the easy hot button issue for the media to frame "should bail reform be rolled back or should it not?"

In the meantime, without much data pointing to the fact that bail reform has had any effect at all, there are all these things that are really serious structural underlying causes that are much more complicated to deal with and make much more difficult headlines to write. Homelessness and the prison-to-shelter pipeline and mental illness and lack of parental or grandparental supervision, after the toll of the pandemic, the real underlying causes that we should be talking much more about proportionately. Thank you for doing it, and thank you for doing some of it here.

Errol Louis: Always glad to be with you, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Errol Louis at 7:00 on NY1 with Inside City Hall and New York Magazine columnist.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.