The Global Vaccination Picture

( Our World in Data / Creative Commons )

[music]

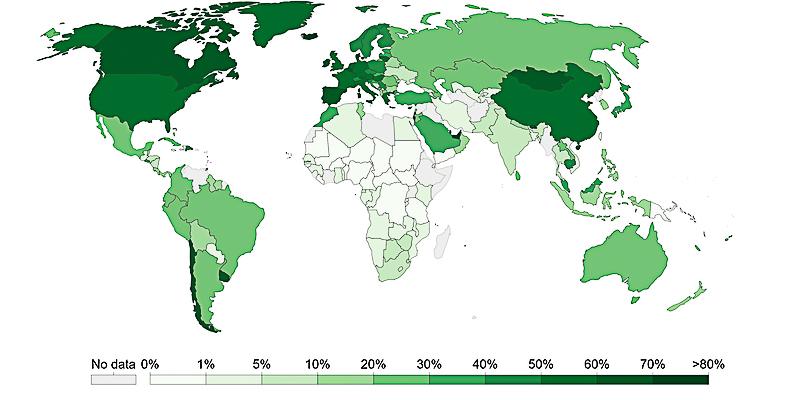

Brigid Bergin: It's the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Brigid Bergin from the WNYC and Gothamist newsroom, filling in for Brian. The US is making plans to offer booster shots of COVID vaccine as early as six months after a full vaccination starting mid-September. That started in some countries already. While Europe and North America have administered over 90 doses of vaccine for every 100 people, that number drops to under seven for the African continent. The director-general of the World Health Organization has called on countries to delay boosters until at least the most vulnerable everywhere have had their shots.

Earlier this month, a group of public health experts and activists organizations sent a letter to the Biden White House, asking for more vaccines and resources for global distribution for the sake of Americans, as well as residents in poor countries. To find out more about why the global vaccination effort is in the interest of US Public Health, we're joined by one of the signatories of the letter, Columbia Universities, Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, university professor of epidemiology and medicine, and director of ICAP, a global health center at the school of public health. Hi, Dr. El-Sadr? Welcome back to WNYC.

Dr. El-Sadr: Thank you. My pleasure.

Brigid Bergin: The WHO's Africa director did not mince words at a press conference last week. Here's a clip of that.

Matshidiso Moeti: Moves by some countries globally to introduce booster shots, threaten the promise of a brighter tomorrow of Africa. As some richer countries hoard vaccines, they make a mockery, frankly, of vaccine equity,

Brigid Bergin: A mockery of vaccine equity. How do you see the global vaccine distribution picture?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think the global distribution picture is very alarming and distressing. I think we all need to appreciate two very important facts, one, that it's absolutely critical that we enable countries around the world to get access to the vaccines because it is the right thing to do in terms of equity, but also very importantly, it is in our own self-interest. We know that as infections surge in any part of the world, this provides a fertile ground for new variants to appear, and then these variants are exactly what can threaten our own safety. I think for the sake of equity and also for the sake of even self-interest, I think it is a critical priority to do whatever we can now to enable sharing of the vaccines, enabling access of the vaccines to the populations of the world.

Brigid Bergin: The organization, COVAX, was specifically set up to ensure that rich nations did not buy up all the vaccines. It has provided something like 170 million doses but that's against a goal of 640 million by this time, isn't it? How is it supposed to work?

Dr. El-Sadr: Well, I think that the main issue is that we don't have a sufficient number of doses of vaccines for the world. Ultimately, we need something, a minimum of 11 billion doses of vaccines in order to just achieve what we need to achieve at this moment in time and the supply is not there and which means that we have to think very carefully about what we can do in the short-term as well the longer term, to be able to produce more vaccines and to make these vaccines available to the people who need them in other countries around the world.

Brigid Bergin: I saw an article in the New York Times that it's not just that COVAX hasn't hit its goals in terms of the dosage, but that even if the doses arrive in the country, there's no public health infrastructure in some of these places to get shots in arms. Can you speak to that?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think we need to focus on what can be done. I would say the number one problem is there aren't enough doses. I think that we should really keep our eye on that problem but of course, I do recognize that we also need to support countries around the world in order to be able to take the doses that they receive and be able to take those doses to the people who need to get vaccinated. We have a lot of experience as a global community in terms of expanding HIV treatment, enabling remote parts of Africa to get access to medications, and so on. We can build on the infrastructure that's already in place to be able to then put forth a strong vaccination program that will enable people to get to the vaccines. It's not simple, but I think it can be done. It also requires, of course, resources and investments as well.

Brigid Bergin: You raised some of your previous work on HIV. I'm wondering, considering what is being attempted on this scale-- Focusing on the things that are going right, what do you think is working and how can we build on that?

Dr. El-Sadr: Well, remember if you think about the HIV epidemic, the first thing we have to do was we had to make sure that there was sufficient medications, antiretroviral treatments, sufficient medications available. The supply of the medicine itself, that's so fundamental. The analogy now is we need the supply of vaccines. We need to be able to ramp up the production of vaccines for the world, wherever we can produce those vaccines as quickly as possible. That's number one. Then I think we need to continue to invest in the health systems that exist in many countries around the world and provide them with the resources and the learnings to be able to take those vaccines when they arrive at the airport and take them to the health facilities, whether they be fixed health facilities or mobile units, for example, to be able to reach far and wide to get people to access the vaccines.

Brigid Bergin: I want to talk a little bit about that letter, you and others sent to the White House that made the case that getting people vaccinated everywhere is good for people here. You've touched on some of the reasoning for that, but explain more about why it's vital and why it's important for people in those countries, why it's important for people in this country.

Dr. El-Sadr: Yes, well, we know that these vaccines are game-changers. They can transform the lives of people. We know that these vaccines are incredibly powerful at protecting people from getting COVID-19. We also know that they can fundamentally improve the outcomes. They decrease hospitalizations, they decrease deaths from COVID-19 and many of the countries around the world are experiencing horrific surges of COVID-19 with overwhelming their health systems, overwhelming the hospitals, running out of oxygen for people who are sick, and in many, many, many other horrific clinical outcomes in many countries. We want to stop that, obviously. We want to stop the suffering, especially when we have something that can stop the suffering.

At the same time, as I said, is once you have infection going on, once you have surges in any part of the world, it's exactly the kind of situation where you start getting new variants and we've had to tackle the Delta variants and enabling the people to be vaccinated around the world can put a stop to the appearance of new variants that may come back to again, threaten us and cause new surges in our own country, or even worse, new variants that may learn how to outsmart our own vaccines. I think it's really to help people around the world who are suffering now from COVID-19 as well to also prevent new variants from arising that could threaten us as a society.

Brigid Bergin: This is the Brian Lehrer Show in WNYC and Brigid Bergin, filling in for Brian today. I'm speaking with Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr about the global vaccination picture, and we can take a couple of phone calls for Dr. El-Sadr. I will tell you, we've had a little bit of technical difficulty with our phones, but we have an amazing technical team who have come to rescue us. We'll take those calls now at 646-435-7280. Do you have friends and families and countries waiting for their first vaccine shot? Does the moral or the self-interest case for devoting more resources to the global vaccination effort makes sense to you? Give us a call at 646-435-7280 or thanks to social media, you can send those questions by tweeting @BrianLehrer. Send your questions however you feel most comfortable, and we'll bring some of those questions to Dr. El-Sadr. Doctor, I'm wondering what specifically is being asked of the Biden administration by the group of public health experts in terms of doses in training?

Dr. El-Sadr: Yes, I think that what would be most vital is to have a plan, a concrete plan in terms of what needs to be done on the short-term and the long-term with very specific timelines and milestones. In our letter, we indicated that the resources are there. It's just that it's unclear how these resources are being used and we're advocating and strongly encouraging that need for a plan that will enable the use of the current resources that have been allocated for the response to COVID-19, to increasing the production capacity of vaccines right now, because I think if we do that, then at least we can meet the immediate needs.

At the same time, we also believe strongly that we would like to also have capacity established in other parts of the world where vaccines can be produced. I think that would be very useful on the longer term for the countries themselves and the regions themselves. I think also for confronting any new threats beyond COVID-19. Having that capacity in place will help, I think will help us down the line as well in what we anticipate might be other viruses that may cause any future pandemics.

Brigid Bergin: Talking a little bit more in detail about some of the constraints to distributing some of these vaccines. I'm wondering why specifically the mRNA vaccines aren't more problematic to administer in terms of refrigeration requirements, and the two shots. Do you have any thoughts there?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think in terms of COVID-19 vaccination, it is a challenge. It has been a challenge even for our very well-resourced country. We've had a rocky road in getting the vaccinations off the ground and that's because this is the biggest ever major vaccination effort of adults. We know how to vaccinate children, but this is a big effort for vaccinating adults. Similarly, it's also new for many countries around the world. I can tell you in countries where ICAP works around the world, including several African countries and elsewhere, we've been able to work with ministries of health to support them in putting together the guidelines and putting together the systems in procuring and securing the refrigerators and the mobile units. It is doable. All of it is doable. We need to make it happen. We need a plan. We need to make it happen. We need to make sure that these countries have sufficient supply of the vaccine, so they can actually mobilize their own systems to get those vaccines to their people.

Brigid Bergin: Let's go to Mark, in Dix Hills, New York. Mark welcome to WNYC.

Mark: Thank you for having me.

Brigid Bergin: What's your question for Dr. El-Sadr?

Mark: The thing is the United States already has the Defense Production Act by which an executive order could have Pfizer, BioNTech, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson, turn over the production formulae for these particular vaccines to whatever facilities are best equipped to produce them and get silence on that front. What timetable would work for that if happen?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think that's a very important tool that the US government has at its fingertips is to be able to rapidly enable the production of more vaccines. I think that's part of what we are urging the administration to do is to think about what are the most efficient, the most rapid things that can be done to get more doses produced. I think that's really the most important. We do recognize that the US government certainly has made substantial donations of vaccines, which is fantastic but it is a drop in the bucket. When you consider the needs out there and donation here, donation there is not going to solve the problem. What's going to solve the problem is the concerted effort with milestones and timelines to produce more vaccines and to get those vaccines to the countries and the people that need them desperately now.

Brigid Bergin: Let's go to Andrew in Queen's. Andrew, thanks for calling WNYC.

Andrew: Hello. Doctor, having listened to your appeal for more vaccination in non-major countries of the world, I understand it's a worthy effort, but I don't see the kind of resources being redirected to make an effective vaccination program worthwhile. In fact, shipping millions of doses into remote, third-world non-infrastructure-laden countries seems to be inefficient compared with completing vaccination efforts in our own country where we're not even approaching any kind of herd immunity or even sufficiently penetrated rural areas.

Brigid Bergin: Andrew, thank you so much for that question. Dr. El-Sadr, I think Andrew is probably giving voice to some of the concerns that we've heard from others. Just in terms of how do you balance understanding, or balance ensuring that folks who get vaccinated here? When we talk about this effort, we're not talking about swelling necessarily vaccinations within the US, but we're talking about the fact that the US is producing such a tremendous supply of vaccines as compared to other parts of the world.

Dr. El-Sadr: Yes, it's not one or the other. I always say that our priority here in the United States is to, of course, try to reach the people who thus far have been hesitant, have not yet gotten vaccinated. That's a very, very important priority, and we need to continue to do everything possible to get individuals comfortable and willing to get vaccinated. That's really, really number one priority in the United States, as well as now to enable a subset of our population, people who are immune suppressed. Those individuals have been identified as a small subset but an important subgroup of our population who may benefit from a booster dose. This is not inconsistent with at the same time, a substantial amount of funding has already been set aside in the American Rescue Plan to try to respond to the global COVID-19 pandemic.

What we're advocating for is that this funding can be utilized now to enhance the production that is needed to be able to get supply for the rest of the world. Obviously, it's not going to be the United States alone, but the United States can be a leader. The United States has been a leader in addressing the HIV pandemic before, and many, many other health threats. It will of course have to include other wealthy countries around the world, but we have the opportunity to be a leader to demonstrate leadership in this really vital effort that the world needs at this point in time.

Brigid Bergin: Let's go to Marie in the Bronx. Marie, welcome to WNYC. What's your question?

Marie: Thank you for taking my call. A few weeks ago, I saw on Chilean news that Chinese representatives were in Chile to proposing to build a vaccinations center, a place where you would mass manufacture vaccines and Chile. It seems a very good idea for at least every continent like Africa, South America, Southeast Asia, they should have their own center of production. What is going on? Do you happen to know professor what is going on? Is there money going to places in these continents too so that vaccines in the future can be made there? Thank you very much.

Dr. El-Sadr: Thank you. Yes, absolutely. That's under when I talk about what can we do in the short-term vs the longer term. Clearly, I think the ultimate longer-term goal is to have that capacity in various regions of the world as you indicate. I think that absolutely needs to be done because I think that we'll be poised then to respond to another threat as well as potentially to this one. I think on the shorter term, and there are investments and there are efforts ongoing to begin to enable the transfer of technology to other countries around the world or build new factories and so on but it's going to take time. It's not going to be overnight. It's not going to solve the problem today. We have to do two things. We have to do what we need to do in the short-term now, which is to enhance the production in the places that can produce a lot of vaccines quickly. At the same time, we are investing for the future in terms of the building, the capacity around the world that would then ensure a future supply of such vaccines.

Brigid Bergin: Doctor, I'm wondering about stories that I've read that J&J in South Africa is producing that vaccine for export. Given the conversation in the question that we just got, why would South Africa not get it first given it's being produced in that country?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think it's absolutely critical that vaccines that are produced in Africa stay in Africa, and where a very small proportion of the population has gotten access to vaccines. There are some countries where it's been 1% of the population, contrast that with now in our country where we're 70%, for example, and so on. There's this huge disparity. I think what we have to do is can we bring equity? Can we try to increase the access to the vaccines in these countries that many, many millions of people have yet to have any hope of getting vaccinated? Of course, any production of any vaccine that is produced in a region of the world, whether it be in Africa or in India, for example, we need to make sure that these vaccines are used in the neediest countries at this point in time.

Brigid Bergin: The director-general of the WHO says there are not enough data to say that boosters are needed. I guess the Israeli data that seemed to indicate immunity wanes after eight months is not convincing enough, but now there are reports that the US will approve booster shots, six months after full vaccination. I'm wondering how you interpret that data.

Dr. El-Sadr: I think, whether it be the data from Israel or the data from the United States, I do not believe that as of yet these data support a recommendation for everybody, for the general population to get a booster dose. I do think, like I said, that for a subset, for people who are immune-suppressed, I think if they would benefit from a booster dose, but I don't believe that at this point it is necessary to require or to recommend that the general population needs a booster dose at this point in time.

I think in the data, what they tell us is that actually, it appears that these vaccines have offered durable protection and that's what you're looking for. There are some studies that look at the level, for example, of antibodies in the bloodstream and extrapolate how much protection one gets from such antibodies but at the same time, we do have real-world data that tell us that these vaccines remain quite powerful in terms of preventing hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19.

Brigid Bergin: Beyond, COVAX, I'm wondering what efforts are underway to provide vaccines or the capacity to produce them worldwide?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think there are beyond the donations or the procurements that COVAX is involved in, for example, the African Union has also been attempting to secure a supply of vaccines for the African continent. They've been direct donations from other countries, direct donations from China, for example, of the vaccines that it produces, there have been also donations from some of the vaccines that have been produced in India. It's a disjointed effort. I think what we are calling for is a concerted plan, is a plan, a well-defined plan that looks at the short term versus the longer term that has milestones and has a timeline and clearly assigns responsibilities for various bodies to be able to accomplish what we want to accomplish. I think that's the way to go rather than depending on donations here and there and a disjointed global efforts.

Brigid Bergin: Interesting. We have a call from Josh in Washington Heights who's raising a question that I think some folks who maybe have had COVID in this country may also have. Josh, what's your question for Dr. El-Sadr?

Josh: My question is why expend these critical vaccines on those who have already been vaccinated-- I'm sorry, those who recovered from COVID? Europe and Israel have exempted those who are COVID recoverers and if we did the same, we could free up millions of dosages because there have been many millions of people who have had COVID and recovered from it. Why don't we adopt that type of policy?

Brigid Bergin: Josh, thanks so much for that question. Dr. El-Sadr, I wonder if you could talk a little bit about I think he's raising that perennial antibody question and why the US policy is different?

Dr. El-Sadr: I think for a couple of reasons, we do have data that tell us that, even in people who have had prior COVID-19 and have recovered, that actually those who get vaccinated thereafter have better protection than those who just have a prior history of COVID-19. That is the reason why the commendations in the United States are for everybody to get vaccinated, who is eligible that irrespective of whether they've had COVID or not, it is because of these data that show better protection once these individuals have been vaccinated.

Brigid Bergin: Before I let you go, Dr. El-sadr I wondered if you could give us your take on some of the vaccine mandates New York City has imposed for dining inside, gyms, city workers, including teachers, and the call for private companies to impose some of the same.

Dr. El-Sadr: I think and as I said before, I feel like vaccines are a game changer and that's something to keep in mind that vaccines not only protect the person who gets vaccinated, but they also protect their loved ones and others around them so it's individual benefit, but it's also societal benefit as well. This makes it very important for people to think about getting vaccinated, to protect themselves, their families, as well as to protect their coworkers and others in the community, and we know that achieving high uptake, high coverage with vaccination at this point in time, and even in the Delta era is our best protection. We know that for example, to protect children in the schools, it is vitally important because many of the young children are not yet eligible for vaccination.

Is that the best thing we can do? One of the best things is to vaccinate adults around them. This means vaccinating their parents, their family members, as well as teachers and staff and so on at the schools, of course, in conjunction with all the other measures wearing masks and having good ventilation and so on in the schools. I think we have to think now in this era, in the COVID-19 pandemic, that the foundation of protection for us has become vaccination and that's the reason why I strongly support expanding vaccination, increasing uptake of vaccines as much as possible, vaccination mandates, as well as trying to work very hard with people who have been reluctant to try to convince them to answer their questions so that they are willing, they're comfortable, and they feel that they're ready to go and get vaccinated.

Brigid Bergin: We'll have to leave it there. My guest has been Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, Colombia University professor of epidemiology and medicine and director of ICAP, and director of the Global Health Initiative at the Mailman School of Public Health. Thank you, Dr. El-Sadr.

Dr. El-Sadr: Thank you. My pleasure.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.