Who Gets the Vaccine When

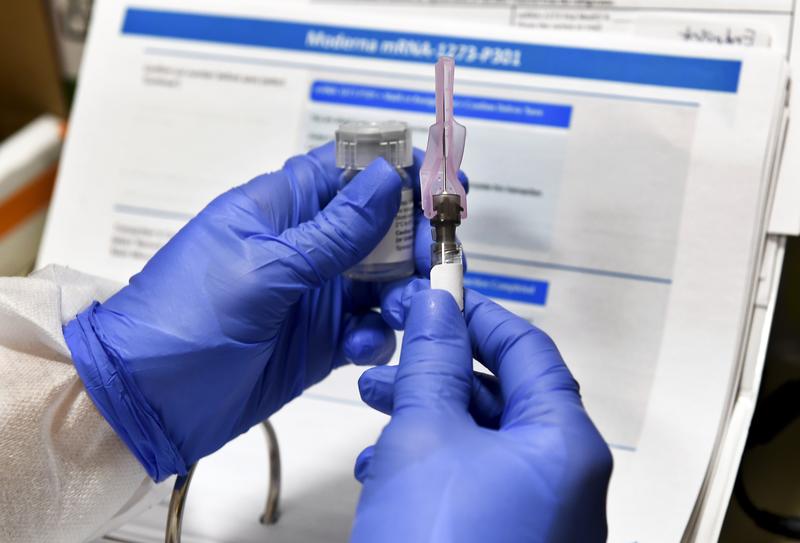

( Hans Pennink / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. A third vaccine manufacturer is now reporting promising results. This time, AstraZeneca. Pfizer has already submitted its request for an emergency use authorization. Moderna is expected to, by the end of the month. If the data holds up and the FDA approves the vaccines, what happens then? The chief scientific advisor for Operation Warp Speed Moncef Slaoui told CNN.

Moncef Slaoui: Our plan is to be able to ship vaccines to the immunization sites within 24 hours from the approval. I would expect maybe on day two after approval on the 11th or on the 12th of December.

Brian: As for Dr. Fauci, he says he expects 20 million people could be vaccinated by early January. How would that happen? To talk more about how these vaccines will get from the manufacturer to each of us and in what order they should, I'm joined by Caroline Chen who covers healthcare, including the coronavirus pandemic for non-profit public interest news organization, ProPublica. Hi, Caroline, welcome back to WNYC.

Caroline Chen: Hey, it's nice to be back.

Brian: Let's establish one thing first. Will the order of who gets vaccine access when be up to each state or will there be federal rules about it?

Caroline: It is going to be up to each state. However, the CDC will provide guidelines and the National Academy of Science and Medicine has already put out guidelines that- has provided a framework, are very high-level framework that states already relied on in their interim plans.

Then the CDC, traditionally, has always had an advisory panel that looked at the specifics for each vaccine once they have all the data and provides further recommendations per vaccine, and that's expected to happen as well, but ultimately each state, because every state has a different population that they have to consider as well, will be determining the final order.

Brian: Let's go down some of what the pecking order is as recommended by the National Academy of Medicine. The first 5% of the population and what they call it "Phase 1a," would be frontline health workers, EMTs, cleaners and first responders. How broad a group is that? I don't know what the word "cleaners" in there means, for example.

Caroline: I think we're thinking about anybody in a hospital setting which could include someone like a janitor who is working, say, in a COVID ward, anybody who is in direct contact with patients would be at the very highest risk so that my colleagues and I, via public records request and as some of these states started to post their plans, we reviewed all the available plans that we could get hold of, and that was consistent frontline health workers, nobody disagrees that they should be first in line.

Brian: Then what the National Academy of Medicine calls "Phase 1b," and other 10% of the population after that first 5%, those with underlying conditions that put them at significantly higher risk, those with two or more chronic conditions and people 65 and older in group living facilities. How will they identify people with underlying conditions that put them at significantly higher risk, or which two or more chronic conditions would qualify to put people in that elevated group? Because, I guess, you could have high blood pressure, but you could just have a little high blood pressure.

You could have high blood pressure that's under control through medication or not. Are those people in the same category? You could have asthma, I've heard that asthma is a risk factor because it's a respiratory condition in many cases. I've heard that asthma, the science shows, isn't really a risk factor for having the worst cases of COVID. So, what's on those lists, or how will they be developed?

Caroline: Yes. I think from what I've seen on the state plans, they're more thinking about groups of populations. They often talk about congregate settings. The most obvious population you want to think about is nursing homes and long-term care facilities, because obviously this is a congregate setting. You have people in close density, and then you have the most obvious high risk factor, which is age here.

That's a very common one where that's the next in line. Depending on which state you're in, that could be a pretty large population already. Then there are other states. Maryland is prioritizing people in jails and prisons along with the long-term care population, their states. There are other states that have that population a little bit lower in their ranking. Arkansas, which has a large chicken industry, has meat packing workers higher up in this population.

I think that's in there one fee. This is where I think states having their own flexibility, to both look at what's in their state, and also may be looking at where they've been hit hard so far in the pandemic, to make their own determinations, within that 1b group, may be useful, and they are thinking, of course, still about-- I think age is a big factor, where people are congregating, these essential workers, people who might not have a choice, but to be working together in close contact is another major factor.

Brian: Listeners, who has a question about the order in which people will be able to get coronavirus vaccines and the timeline? 646-435-7280, for Caroline Chan from ProPublica, who's covering this. 646-435-7280. We'll keep going down that pecking order guidelines list from the National Academy of Medicine and also talk about how it's being tweaked for different states and their different populations as Caroline was just explaining about our console and the meat packing plants, for example. 646-435-7280. Julie in Chatham, you're on WNYC. Hi, Julie. That's Chatham, New Jersey, not Chatham, New York, right?

Julie: Correct. Thank you so much, Brian and Caroline. Brian, I've called a few times already, love the show. I don't know how to survive without it.

Brian: Thank you.

Julie: A couple of things. One is, yay to AstraZeneca, because they are doing the far more equitable in their process, and I think following the UN or WHO guidelines, which is a little bit of vaccine, a lot of places, as opposed to a lot of vaccine in a few places, should also be followed suit with our rollout. I think it's backwards.

I think we have so many people that are not mass compliant to the general population who are overwhelming the institutions. Meanwhile, the health firstline workers, if they have the PPE, they are compliant. I'm compliant. I wear my homemade mask. I don't want to be first in line to get the vaccine, but my neighbor who doesn't wear a mask, I want him to get the vaccine. You understand?

Brian: Caroline, a lot of people have those thoughts.

Caroline: Yes, I think one thing that maybe we should even back up and say here is, it doesn't matter how effective a vaccine is. 95%. Some of these members we're hearing so far, I hope they continue to bear out as the trial is complete, but even so these numbers we're seeing are fantastic in the trials, they exceed expectations, but at the end of the day, this is only going to make a difference independent, if people get the vaccine, right?

You can have a 95% effective vaccine and have only 20% of the population take it. It's not going to have a humongous dent on the pandemic as if 70% of the population gets it. The rollout is really the part which is going to matter the most. This is the part where both having an effective rollout where there are no stumbles and also really public communication at federal state, local levels, explaining the vaccine to people, getting over vaccine hesitancy, which has been growing across the US and in many places globally, that's a big hurdle in some areas.

Then, of course, not having hiccups in a delivery and then on the pharma side manufacturing, there are a lot of steps that need to continue to go right. Getting the vaccine right in the clinical trials is just step one. All these questions of who should get it, you could have someone who you believe should get the vaccine and they don't want to get it. Then want?

Julie: Fair point. I agree with that. You're right.

Brian: Julie, thank you very much. Let's go to Carol in the Bronx. Carol, you're on WNYC. Hi there.

Carol: Hi. This all makes a lot of sense to me, except one thing, you've just barely touched on it now. The essential workers, the ones that have to go in the grocery workers, the delivery people, those people that have to be there. I'm not sure why they don't get priority.

Caroline: Still in many cases, they are part of this- they are high priority. They are in what's called "Phase 1b" in the states they're counted as essential workers. I would call them definitely high up there in the priority scheme, and again, it goes dependent state-to-state.

Carol: I haven't heard that.

Caroline: Yes, it depends. A lot of states are starting to put out their plans on their website, or ProPublica where I work, we are making public what we have managed to gather from the states.

A lot of these plans are interim plans because they wanted to see the actual data from the vaccine trial sorts of states will be modifying their plans as they go, but you can also go look at your state and see how they've set-up their priority order, but of course, what you said makes sense. People who are essential workers who are in crowded areas like grocery stores are going to be people who are at much higher priority than someone like me, who is mostly working from home and it doesn't have to go anywhere to do my job.

Brian: Carol, thanks for raising that question. Let's keep going down the pecking order again and again, these are general guidelines that were issued by the National Academy of Medicine, though most states, and it's up to the states, are following something roughly like this, so this will help you get an idea. We already talked about the top 5% of people, what they call "Phase 1a," frontline health workers, EMTs, cleaners and hospitals and places like that, and first responders, then the next 10%, those with underlying conditions that put them at significantly higher risk, those with two or more chronic conditions, and those 65 and older in group living facilities.

Then the next third of the population, after that first 15%, would include all people over 65, critical workers in high-risk situations like teachers and childcare workers, those with an underlying condition that puts them at moderately higher risk rather than significantly higher risk, and all people under 65 who are in prisons, jails and detention centers. All of those people together make a third of the population roughly, and that's a lot of folks.

Caroline: Yes, that's a ton of folks at that point. This would be past that January point, what you mentioned right at the top of your show, that government officials have been saying, initially we expect about 20 million doses, this is what we've had estimated from Pfizer and Moderna, that will get us through the end of the year, and then may have factoring is expected to kick up far more by early 2021 into the spring, and we'll be able to get that out to the broader population by then.

Brian: Let's take a call on one of those groups that I just mentioned in that Phase 2, [unintelligible 00:13:12] in the Bronx. You're on w NYC. Hello, [unintelligible 00:13:15].

Caller 3: Hi. You actually just mentioned the prison population, but I was wondering how that will be administered. Would it be to everyone in the prisons? Because they can't socially distance the way we can at home, or is it dependent on whether someone has certain illnesses like diabetes or asthma, or the other ones that you mentioned that could put you at higher risk? How will that work in regards to administering the vaccine?

Brian: Caroline, how clear is that at this point?

Caroline: That is unclear to me, and I haven't actually seen any plans that I've gotten down into that level of nitty-gritty. As I've mentioned, I've only seen maybe one state that has the prison population put into their 1b category for most others that has further down in their second tier, or not in their second highest, the 1b versus the 1a group, so it really is state by state.

I think that kind of logistic, you said, who in the prison population, is it everyone versus, some is still being worked out, frankly. A lot of these finer details will be reliant on things like how many doses will be delivered in one go. One of the things that I've been reporting on, and Brian and I discussed this at greater length, is some of the restrictions around storage for these vaccines.

Pfizer's needs to be ultra-cold. There could be a case where, if it has to be delivered to you in a batch of, say, 500 or whatever, it's easier if you have to use it all up, rather if it can't be slipped down to the smaller numbers, but if it can be split down into smaller numbers, say the Moderna is a little bit easier to handle, you might have more flexibility in how it can be parceled out. Things like that, which are more logistical in nature, are still being worked out by the manufacturers and the states are in some ways being put in a position of waiting for all this information so that they can then plan out that put a finer detail.

Brian: For example, in our last segment, we were talking about Fort Dix in New Jersey, which has the second highest concentration. I think the stat was of coronavirus in the federal prison system, the prison at Fort Dix, and New Jersey in general, some of the particular institutions have higher rates than in other places. Would that be taken into account when figuring out what prisons might get it first?

Caroline: Yes. I'm sure that the state level health department will be looking at where in our state has the biggest problem spots been so far and take that into account when they're thinking about how do we take the vaccine that we're getting from the federal level that's being distributed to us and how do we then take a look at where our outbreaks have been and how we can then distribute accordingly to try to get our state's outbreaks under control. I think all, both still being figured out at the state level and also something that they will probably have to be somewhat flexible as the vaccine gets rolled out to them.

Brian: Here's Jesse, a college student in Manhattan. Jesse, you're on WNYC. Hi.

Jesse: Hi, thanks for taking my call. I have a question about college students in the vaccine, not because college students deserve it or because we're going to be more susceptible to the virus, but just because college students and off-campus parties have been such a source of superspreaders of the disease. I'm just wondering to what extent living in a community that is going to be taken into consideration when they're thinking about distributing the vaccines.

Caroline: Yes, that's a great question and I'm glad you've asked. Most of the plans that I've seen in the guidelines from the National Academy has put young adults in Phase 3. I think that is mostly coming from the data that we've seen so far that, just relatively speaking, the elderly and the older that you are, the higher risk you are at from a bad outcome, if you do catch the coronavirus, and that has accordingly pushed young adults and children as a lower priority group.

Given that, I don't think that young adults or college-aged students are going to be anywhere near the front of the line, and I've not seen that in any state plans. Whether or not there's any special consideration because of college settings, I have not seen that so far, but it'd be interesting. One of the things that is interesting that you're raising here is, how colleges will be part of the distribution plans and how they'll be looped into coordinating distribution, potentially for any colleges that have students part-time or to any degree attending in-person.

I haven't really seen that so far, so that's definitely something that I'll be looking out for in future reporting. I appreciate you raising that question.

Brian: Yes. Jesse, for your information and for everyone else's on this National Academy of Medicine blueprint, it does specifically say for the lower half of people, young adults, children, if safe for them. I think these vaccines haven't been tested on children yet, but it says, young adults, children of safe and people who work in industries such as higher education, hotels, banks, and factories. Higher education has mentioned there, and young adults.

It's interesting, Caroline, that what you were keying on and what the color was keying on, they don't key on this specifically, people living in congregate facilities, particularly dorms with singling them out, but maybe when they get to that lower half, and again, these are just guidelines from the National Academy of Medicine, each state is going to come up with its own actual distribution plan and more minutia, maybe they'll go to college students in dorms before they go to other people in that group.

Caroline: Yes. Just on the note of children, so Pfizer has expanded its trial on into children as young as 12, and as far as I know of the leading manufacturers who have vaccines in Phase 3, they're the only one who's gone that young, but it is critical that vaccines be tested in children before they allow vaccination in those ages. They wouldn't release vaccine for children before they're tested in that population, and the FDA has been very clear about that, and the external panel of FDA advisors called the advisory committee, has also been very clear that they want to see that data first.

Every manufacturer that I've talked to has been clear that that is in their plan and they will move into that population, but this is very typical, because we want to be careful about safety and children that we test in adults first, and when it looks good in adults, we move into children. That also makes sense for the coronavirus because children, fortunately, tend to have better outcomes, they're not the most urgent priority group to be tested.

Generally, it will follow the pattern of what Pfizer has done, where when safety has looked pretty good in adults, they start expanding the trial to include younger populations, and so I expect to see a similar pattern for Moderna and for other vaccine makers. Once that data looks good, the FDA will probably extend the allowance to say, "You can now use it in younger populations," but they wouldn't just say, "Oh, we only have data in adults, you can go ahead and vaccinate children."

Brian: Right, and this National Academy of Medicine guidelines seem to separate teachers in, let's say, everything up through high school and those teaching in higher education because teachers and childcare workers are listed as a group in the first half of people, but people who work in higher education are listed as a group in the second half of people. Presumably, people in the college community, whether faculty and staff or students, wouldn't be in line until next summer or so, yes?

Caroline: Yes, or next spring I think, it really just depends on how much vaccine we get and how quickly we get, because so far, the data has looked really good, and so now it's a question of manufacturing speed.

Brian: Jeffrey in Harlem, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jeffrey.

Jeffrey: Oh, hello. My partner is a doctor who's caring for COVID patients, and I'm wondering if there's any thought given to the family members of medical workers and whether we're going to be given the vaccine or whether they're counting on a vaccine for the medical workers to protect the family members. I'll take my answer off the air. Thank you.

Brian: Thank you, Jeffrey. That's a great question, and I don't see that category at all on this National Academy of Medicine chart. Of course, the very first category is frontline health workers, so that would include his partner who's taking care of COVID patients, but what about family members of them?

Caroline: I have never seen a description of a category of family members, so I don't think that they typically would be included in that Phase 1a group, as far as I've seen. Of course, there's discretion, as we've discussed, on state by state, but my feeling is typically that they would expect that the vaccine would protect the frontline worker and that that then should provide protection to their family members.

I think that this is partly driven just by scarcity. Initially, we're going to have not enough vaccine for everyone, and so the feeling is that we just really need to triage it to those who are at highest risk, those people who are directly face to face with COVID patients day in, day out.

Brian: One last thing before you go, and thanks for so much great information. Again, you're doing such good work covering the aspects of-

Caroline: Thank you.

Brian: -of COVID that you're covering there at ProPublica, so thank you for coming on again with our second time in just a few weeks on different aspects of the vaccine story. The federal government will distribute these millions of vaccines to the states, as I understand it, according to their populations. If this starts when President Trump is still in office, that threat that he made to skip New York because of things that Governor Cuomo is saying, can actually be part of the plan, can it?

Caroline: I've really hoped that politics does not, yet again, come into this aspect. That would be really disheartening, but I do think that this is an aspect where there's so many professionals who are working on this, not only at Operation Warp Speed, but at the CDC, working on distributing these vaccines, and everybody just really wants to get them out.

I'm really hoping that it's done in a very clear cut way. I think population is probably going to be the biggest factor, but I also wonder, and I don't have any specific information on this, but after a while, whether infection rates will come into play, and that would also make sense.

Now, currently, as we all know, the virus unfortunately is pretty much raising across the whole of the US, with very few exceptions, so I guess population would probably make a lot of sense, but if we return to the scenario more like the summer where there were certain states that were particularly hard hit while others were relatively speaking untouched, it could make sense to be pushing the vaccine more heavily to some states or not.

I know the CDC is working very hard on having data flow up to it from the states and they're creating data pools, where they're going to ask states to be reporting up to them on sort of vaccination rates, so that they can keep track of how much vaccine has gone out to each state and the need. This is going to be a massive operation. It'll be really interesting to see how it goes, and I really hope that it goes smoothly.

Then the other aspect we haven't talked about at all, but I'm happy to talk about with you more another time, we'll be tracking the safety and looking out for any safety issues, and again, that is going to be one massive state-by-state federal level data coordination and tracking effort, so there's going to be much more for us to be watching out for.

Brian: Caroline Chen from ProPublica, thanks so much.

Caroline: Thank you. Bye.

Brian: I'm Brian Lehrer on WNYC, more to come.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.