The Georgia Grand Jury on Trump and the 2020 Election

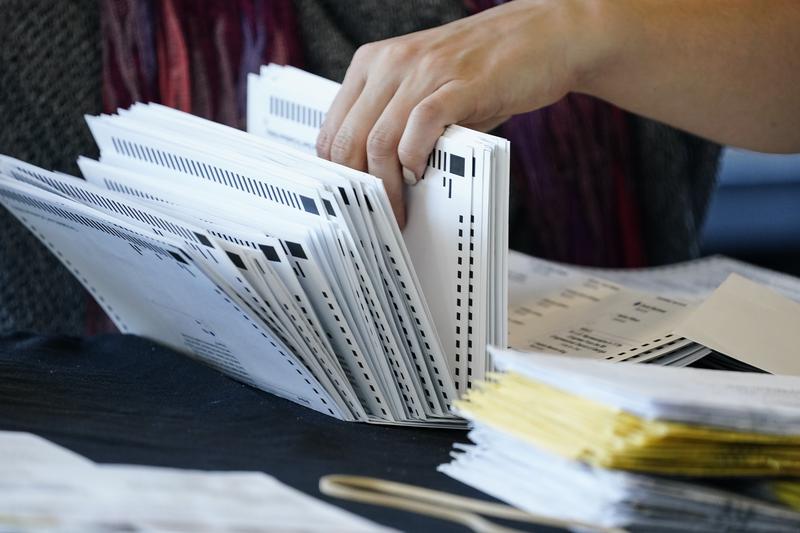

( Brynn Anderson / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We could soon know if a grand jury in Fulton County, Georgia, that's the Atlanta area, will indict Donald Trump or anyone else for trying to tamper with the outcome of the presidential election in that state. As you probably heard Fulton County DA Fani Willis told the court last month that a decision is imminent, and yesterday, as you probably heard, there was a partial release of the grand jury report after they heard from 75 witnesses. One headline is that they found no evidence of widespread voter fraud. Another is that most jurors think one or more witnesses perjured themselves in their testimony.

Now, witnesses included many marquee Trump world names including Rudy Giuliani, Lindsey Graham, John Eastman, Newt Gingrich, Michael Flynn, and others. Also, Georgia officials who resisted the call to flip the election including Brian Kemp and Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger to whom Trump made that infamous phone call asking him to find the exact number of votes Trump needed to reverse the outcome.

Let's get insight into what we can learn from reading the grand jury report and from reading between the lines with a special guest who would know how to do that, Andrew Weissmann, who has so much relevant experience. He was general counsel to the FBI, he was a lead prosecutor in Robert Muller's Special Counsel's Office in the Donald Trump Russia investigation, and he's the author of Where Law Ends: Inside the Muller Investigation. Now, Andrew Weissmann is professor of criminal and national security law at the NYU School of Law. Andrew, great to have you on again. Welcome back to WNYC.

Andrew Weissmann: Great to be here, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: The top headline in most news reports, as I said, is that by a unanimous vote, the grand jury concluded that no widespread fraud took place that could have legitimately overturned the election in Georgia. I've been wondering since I saw this yesterday, a grand jury is there to decide on criminal indictments. Why did they even take up the question of the legitimacy of the election itself?

Andrew Weissmann: Well, that's a great question. I think the first thing it's important to understand is that this is an oddity of Georgia practice where there are two types of grand juries. This is a grand jury that actually just investigates and writes a report. It doesn't actually have the power to indict. When we normally think about a grand jury, and certainly in the federal system, it is just as you said, a grand jury that just decides is there probable cause that a specific person committed a specific crime, and they go through the evidence with respect to each potential crime and each potential defendant.

Now, having said that, it is irrelevant whether there was widespread fraud. It doesn't get you all the way there, but if you were going to indict somebody for engaging in election fraud or voter fraud or campaign of improperly influencing electors, the prerequisite to bringing that case is that there in fact was no voter fraud. It doesn't get you all the way, as I said because you have to also show that the potential defendant you're considering understood that at the time.

In other words, if they knowingly were saying something that they knew to be false. For instance, if Donald Trump actually believed there was voter fraud and was saying to Georgia, "There actually was a voter fraud, and we need you to look into that," the fact that he might have been wrong about that conclusion wouldn't make it criminal. Now, having said that, I think there's a lot of evidence to show his actual intent, but that is why a grand jury would be making that initial finding, which we learned about yesterday.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to get to a clip from that famous phone call, but not the famous clip from that famous phone call that I wonder which side of intent it actually would land a jury on. Staying for a second on the question of the grand jury considering the case for a stolen election or not itself. Did they hear evidence, or did they hear competing arguments about that question before they drew their unanimous conclusion?

Andrew Weissmann: That's also a great question. Well, presumably they did. They obviously decided that the evidence that they heard saying that there was voter fraud is something they didn't think in fact happened. One example that we can be pretty sure that they heard was that they would have heard the famous Raffensperger tape, and they apparently also heard directly from Raffensperger saying that there was no voter fraud.

On the other hand, obviously, if they heard that tape, they heard the former president saying that he understood that there was voter fraud. They did certainly have competing evidence, and they made their own judgment that the Donald Trump version that there is voter fraud was wrong. It still remains to be seen whether they're going to-- they also concluded that it was intentionally wrong, as opposed to just an erroneous assumption.

Brian Lehrer: Let me ask you about the unanimous part of that finding of no widespread voter fraud. The word unanimous, I think, is going by very quickly in these news reports. Regular juries need unanimity to convict, grand juries only need a majority to indict or in this case to make a conclusion. I've been on the New York grand jury, 23 people as is the practice if I recall correctly, and I was surprised to learn at that time that we can indict people and really change their lives by making them criminal defendants with a simple majority vote. In that context, is the unanimity on no widespread election fraud even more remarkable?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes, but I would caution, as you know, probably from your own grand jury experience that, yes, you only need a majority, but it's also worth noting that the standard of proof is just probable cause, it's not proof beyond a reasonable doubt. It's easier for the government to get that unanimity. As you mentioned at the outset, it is interesting to me that there was unanimity with respect to this issue of whether there was voter fraud where everyone was unanimous that there wasn't, but apparently, there isn't unanimity with respect to whether one or more people committed perjury because the language that was used was that the majority of the grand jurors found that.

Brian Lehrer: I was just going to ask about that distinction because that's going by very quickly in the news reports. Unanimously, they found no widespread voter fraud, and a majority found that one or more witnesses probably perjured themselves. Those are different.

Andrew Weissmann: Absolutely. It does to me suggest that the grand jurors are being very careful, and this isn't just people who are-- people like to say that a grand jury is just a rubber stamp for the prosecution, and that would suggest people are really quite discriminating and being very careful. That was at least what I took from that.

Brian Lehrer: Before we move on to that other finding by the grand jury, and a little more detail about the potential perjury, it's probably worth putting this unanimous vote about no widespread election fraud in context as the latest in a very long string of judicial branch findings that the election was not stolen that dates back to the fall of 2020, right?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes. You can add this to 60 court cases. The then Attorney General of the United States, who was certainly no antagonist of the president, at least at the time. His chief campaign managers and pollsters, and apparently, according to news reports, they actually hired a firm to do research into whether there was any fraud, and they privately concluded there wasn't and importantly told the president and Mark Meadows that they did not find any widespread fraud.

If you add that all up, you understand why the grand jury here made that conclusion. If there has to be a charge in Georgia or federally on this issue, it will be very, very strong proof that the government will be able to bring to bear.

Brian Lehrer: All right. Now to this majority of the grand jury finding that one or more people probably lied at the level that it would be perjury under the law. That they want those people indicted who might have lied, and about what if you as a former prosecutor can read this in a way that most of us can't?

Andrew Weissmann: Sure. First as a former prosecutor, and certainly, I think it's worth everyone noting that in public corruption cases, everyone that I've done, this is par for the course. It is just a rampant problem of witnesses who make false statements to the FBI and to prosecutors and even go so far as lying in the grand jury. It is one of the reasons that it's really important that there's some disincentive. That's a long way of saying it's really important when you have the proof to bring that charge if you're trying to deter people from doing it. It's one of the reasons when I worked in the Special Counsel Mueller Investigation, we brought false statements and perjury charges for that precise reason to make sure that at least those people who could be deterred would be deterred.

I wasn't surprised to see that at least a majority thought that at least one of the witnesses lied. Especially, if they heard from people like Michael Flynn. Michael Flynn has admitted now under oath that he lied to a federal judge. He obviously lied to the Vice President of the United States. He lied to the FBI when he was interviewed. This isn't somebody who has a history of being particularly candid. Again, I don't know if that means that he, in this instance, lied to the grand jury, but there certainly are people who would be willing to do so.

The other thing I just would like to point out is that sometimes these what are called hostile witnesses, people who are aligned with the other side can be very interesting government witnesses. I'm a New Yorker as I think you are, Brian. We all lived through the Trump Organization trial. The one where Alan Weisberg pled guilty and was one of the witnesses. The Manhattan DA made their case almost exclusively through witnesses who were so-called hostile witnesses.

Mr. McConney, for instance, clearly said things that the government said were not true. They presented that to the jury saying, look at the way in which the Trump organization is defending itself in their story. It's just not plausible. The fact that there might be witnesses who lied to the Georgia grand jury doesn't mean that those witnesses might not be able to be called and help essentially put on the defense in the worst light possible to an actual trial jury.

Brian Lehrer: Now listeners, your questions welcome about the election coup investigations in Georgia and at the Justice Department, which we'll get to a little of, for former FBI general counsel and former Russia investigation, lead attorney Andrew Weissman, now teaching at the NYU Law School. 212-433 WNYC, 212-433-9692. You can tweet a question or a comment @BrianLehrer. Andrew, 18 people I see got letters saying they were targets of the investigation, I guess meaning that they are being investigated for potential criminal charges. Would I be right to say targets don't get called as witnesses? All those people close to Trump who testified Gingrich, Giuliani, Flynn, John Eastman, they're not going to be charged with election tampering.

Andrew Weissmann: Generally speaking targets are not put into the grand jury without a lot of high-level approvals. You technically can put a target in the grand jury. Just to analogize to the federal context. If Donald Trump is a target of a federal grand jury you would normally need very high-level approval to put him into the grand jury. That's because of due process concerns about somebody who is actually a target of the grand jury. It's just all internal rules. It's not a legal requirement.

It's out of respect for the due process rights of that person. You can be a target and you could be indicted and you could be a target where the government ultimately decides that there is either isn't enough proof to indict or there is enough proof, but they decide for other reasons that you shouldn't be indicted. For instance, the crime that they're thinking of charging you with is not one that's normally prosecuted by the department, then you would definitely weigh that in favor of not bringing a charge and not having what's called selective prosecution. The fact that you're a target, the bottom line as it sounds not a good thing because it certainly suggests that the government is certainly trying to make a case on you.

Brian Lehrer: The DA Fani Willis was against this report being released, the grand Jury report being released. Here's a clip of her in court last month because they have cameras in the courtroom in Georgia, which we don't have any in state of New York. In court, last month, worrying to the judge about, why?

Fani Willis: We think for future defendants to be treated fairly is not appropriate at this time to have this report released. I, as the elected District Attorney, have made several commitments to the public understanding the public interest around this case at this time in the interest of justice and the rights of not the state, but others. We are asking that the report not be released because you haven't seen that report decisions are imminent.

Brian Lehrer: This is another thing that as this story broke yesterday, and I was getting familiar with it myself, had me scratching my head, Andrew. This is DA Willis's own grand jury report, and she doesn't want it released. Who did? How did that happen?

Andrew Weissmann: This is because of the anomaly that there are these two types of grand juries, one that is issuing a report and one that gets to indict. What she's doing is what I call the anti-Jim Comey approach, which is that she-- and then what I'm referring to is Jim Comey announcing that he recommended there wouldn't be charges against Hillary Clinton, and then the course of which she completely-

Brian Lehrer: Threw her under the bus in the presidential election.

Andrew Weissmann: Yes. He gave his opinion about all the things that she did that he thought was wrong, that that violates looks every precept of the Department of Justice to do that. What she was saying is, I don't do that. If there is a report that names people that we ultimately do not charge, it is not fair to publicly tar them with this grand jury report. I thought one of the more interesting things about the report that was made public yesterday is something that didn't get a lot of attention. On the very last page, the special grand jury that issued the report said, "Yes, we do want this report to be made public," but they said, "We take no position as to when the report is made public."

That really supports what the DA wanted and what the court ultimately concluded, which was that the only parts of the report that would be made public at this time don't name names. It's out of respect for that. What I used to colloquially say is put up or shut up, meaning that the government is not supposed to just announce who they think as bad and has done something corrupt. You either are indicting or you're not. That's your role as a prosecutor. It's not to be a pundit like I am and say what I think about people.

I really do think she's taking the responsible position. I do think that the court took a responsible position in terms of how it's handling the due process rights of those people who may have been named in the grand Jury report.

Brian Lehrer: There were a lot of redactions in this report for people who see the physical thing. DA Willis did say this week that she was satisfied with the release as redacted. Do you think there is no risk from this either to potential defendant's rights for rights own sake, or to a conviction being overturned on appeal for biasing the jury pool?

Andrew Weissmann: Well, I don't think what came out yesterday will ever be able to make any valid claim about that. I do think that what the DA was worried about was that if it did name names it could affect exactly that. Even more so, I think she was thinking about what if there's someone named who is not eventually charged, that fundamentally would be a repetition of what Jim Comey did with Inspector Hillary Clinton. She didn't want to be in that camp.

I think where we are now, she has preserved all of the due process rights for those people. I think it's a real testament to both the DA and to the court in terms of how they're handling this. It's a good lesson for the public to know as why they're doing this, that they don't want to be in that position where a prosecutor in the court is overstepping their proper role in our system of justice.

Brian Lehrer: Before we take a break and then come back and I ask you if you think based on this report that Donald Trump will be indicted. The DA told the court there that decisions about filing charges are imminent. In your experience, how long from now is imminent?

Andrew Weissmann: That's what we used to call, Brian a compound question. The first is, do I think that there will be a charge against Donald Trump? I do. I think that it's obviously speculation. It's tea leaf wilting, but I think that the way in which the court and the DA discussed this at the hearing, the way the report reads, it just doesn't read like they concluded by a majority that there were no crimes here. I do think that we could anticipate that. The issue of what does imminent mean? That I can't guess. That's one of those things where I actually suspect that what the DA is doing now is less calling new witnesses into the grand jury.

I think we would learn about that, if that was what was going on. I think there's a lot of things that are happening behind the scenes that you have to be prepared for. What I mean by that is, once she brings charges, she has to be prepared and have her papers. Her written papers in order when, let's say Donald Trump says there should be a change of venue to move it out of her district. There should be a change to bring it to a federal court and take it out of the state court.

All of those are things that she wants to be prepared and briefed and have those papers completely ready. There is a lot of paperwork in my experience that goes on behind the scenes, not just simply the charging instrument that is the indictment. I do think that there's a lot of work that she may be doing at this point. I really base that on the fact that we're not seeing any new grand jury work.

Brian Lehrer: If I understood you correctly about how there's a separate grand jury to do this report from a jury that would actually indict people. There's a whole second grand jury. Has that grand jury already been seated and is in the process of hearing arguments about people who might be indicted?

Andrew Weissmann: The reports are, yes there has been a so-called indicting grand jury. The one that can actually bring those charges. It's important to note that, that grand jury you don't have to actually reinvent the wheel. You don't have to recall all of the witnesses. You don't have to submit all of the written evidence again.

You can, for instance, take the transcripts of the prior grand jury and just submit them to the new grand jury and you can also have an agent go in and present a summary form and walk them through the evidence. It can be a relatively short procedure to do all that. Now, obviously, if the grand jury has questions and wants to hear from direct witnesses, that could obviously take some time.

Brian Lehrer: All right. Listeners who heard me ask Andrew one of my questions in a certain way a couple of minutes ago realized we got a little spoiler in there by accident. He did reveal whether he thinks Donald Trump is going to be indicted by this Georgia grand jury and he said that before the break. When we come back after the break, I'm going to play another clip. Not the famous find 11,780 votes one from that hour-long conversation that I would imagine the defense might use to avoid conviction if he is indicted.

We'll pick it up from there with former FBI Special Counsel, former Lead Prosecutor in the Mueller investigation, Andrew Weissman, and you at 212-433 WNYC. Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we continue with Andrew Weissman, former FBI General Counsel, former Lead Prosecutor in the Mueller investigation. Now a professor at NYU Law School, as we talk about the grand jury report released yesterday in the Fulton County Georgia election tampering investigation into Donald Trump and others.

I see the calls are coming in are all about the Department of Justice Special Counsel, January 6th, investigation into Trump and others. There are some new developments in that this week and we'll get to that a little bit with Andrew Weissmann. Callers, if you're on that be patient. We're going to stay on Georgia here for another few minutes. I pulled two different clips, Andrew, from that hour-long phone call. Different from the one everybody hears all the time. I want you to find 11,780 votes or whatever the number was. In order to aim for more context, so here's one that I wonder if it helps Trump in a hypothetical trial.

He's just gone through in the phone call a litany of allegations of massive election fraud, all of which we should say were found to be false. Like hundreds of thousands of ballots being dumped from mysterious trucks and thousands of dead people voting all false, but then he says this to Brad Raffensperge.

Trump: Brad, if you took the minimum numbers were many, many times above the 11,779 and many of those numbers are certified or they will be certified, but they are certified or those are numbers that are there that exist and that beat the margin of loss. They beat it by a lot. People should be happy to have an accurate count instead of an election where there's turmoil. There's turmoil in Georgia.

Brian Lehrer: He's making an argument there that would provide an accurate count. Andrew, I wonder if that context helps Trump in a hypothetical trial. Because at least sounds like he's not trying to just get a squeaker of a margin for his own victory sake based on lies, but that the true margin is a runaway in his favor and he seems to believe it, even if he's deluded. Does a clip like that matter in court?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes. Look he's going to if he's charged say, "I may be erroneously, but at the time truly believe that I'd won by a lot and the reason that I asked for them to find just this number is because that's the only relevant number." In other words, it doesn't matter if there's more than that number because I still will have won. I needed them to pick this number and get to that number legitimately.

That would be his argument. The fact that it was totally wrong and there were no facts to support him is not going to be a good fact for him. Now it doesn't go to totally prove his intent, but the fact that there's still been no evidence of that and that people were looking for it, and that he was told repeatedly that that was not the case, those are not good facts for it. I think the other thing that's gotten less attention, that is a really good fact for the government here is his threat of criminal prosecution of Brad Raffensperger.

Donald Trump doesn't say, "I know that there was fraud." He said, "I believe there was fraud." Yet he goes out of his way to say, "Brad, you and your lawyer are facing criminal prosecution, because you know that there was fraud." That's not true. Brad Raffensperger saying, "I don't know there's fraud." To threaten him with criminal prosecution, when I heard that part of the tape, frankly as a former prosecutor was thinking bring it on. Like I am ready to go to trial.

I think if you have trial jurors who have any common sense, you're going to be thinking, "Why is he raising the threat of criminal prosecution for somebody who himself has a good faith belief that there was no fraud?" I think yes, Donald Trump will raise his defense, he's entitled to. That's what defendants are entitled to raise all those arguments. The government has to disprove it and has to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. I'm not sure that the clip you played in context is going to get Donald Trump where he needs to be.

Brian Lehrer: I have that clip where Trump appears to threaten Raffensperger and one of his employees if they don't play Trump's game. Here it is.

Trump: You're going to find that they are, which is totally illegal. It's more illegal for you than it is for them, because you know what they did and you're not reporting it. That's a criminal offense. You can't let that happen. That's a big risk to you and to Ryan your lawyer. That's a big risk.

Brian Lehrer: That's outrageous Andrew, but what's the crime there? If they were to charge Trump with a crime based on saying that to Raffensperger, what's the name of the crime?

Andrew Weissmann: Just remember that could be evidence that Donald Trump intentionally knew he had lost and was making an intentional falsehood. That is interfering with the Georgia election and there are a whole host of state crimes that goes to making a false statement to an election official. Brad Raffensperger is an election official. You would use that to prove that. You don't have to charge the act solely, look at the actual statement and say that's a crime. I would say on the federal level, and this may be a good segue to what we're going to get to. At the federal level, it certainly looks like extortion. Which is using his public office to extort an official to do something against his duty as a public officer.

There are at least potential federal crimes that statement alone could prove up. Certainly, Jack Smith as a former head of the public integrity section at the Department of Justice is going to be well aware of those types of federal crimes.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a call about the Georgia case. Edmond in Westchester, you're on WNYC with Andrew Weissman. Hi Edmond?

Edmond: Hi. I just wanted to bring up the point or question that when Trump stated that it was certified or going to be certified at levels three times higher than what he was asking for. Is it not possible that he was talking about the certifications that were being made? One could easily say fraudulently, on his behalf. In fact, that there are politicians in the GOP who might be held accountable for creating these fraudulent documents. In other words, when he made that statement, it may not have been of unknowingly knowing the truth, but in fact, knowing that he had arranged for these alternative certifications to be produced.

Brian Lehrer: Andrew?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes, absolutely. One of the things that we know that the federal government is looking at is just that is the procurement of these slates of fake state electors to be able to essentially put pressure on Mike Pence and Congress to accept them and not the true electors on January 6. I think that is something that could be worked into the Georgia potential charges, but it certainly is something that Jack Smith is looking at. We know the Department of Justice announced even ahead of the January 6 hearings that it was looking at the slate of fake electors in Georgia and other states as a way to undermine the transfer of power.

Brian Lehrer: On that word certified from the clip, from the phone call that we played. I didn't draw attention to this before, but I think it's a perfect example of how Trump uses rhetoric in a way that dances around the actual truth that he may know, and yet lands on a word repeatedly that he wants people to retain. Just reading from the transcript of the clip we just played, many of those numbers are certified or they will be certified, but they are certified. Those are numbers that are there that exist.

He's saying these numbers showing that he won Georgia by a lot, are certified, which they're not. Then he gives himself deniability. He says, "Well, or they will be certified." Then he comes back to, "But they're certified."

Like they may not be officially certified, but I'm calling them certified. Then he says, "But those are numbers that are there, that exists." Just by saying there are numbers that exist in the conversations that he and his people are having, that lands back to a listener hearing the word certified three times in that little phrase when certified suggests something official. Is that typical of how Trump uses the English language?

Andrew Weissmann: I just think that's such a good point, Brian. You really have the sense that Donald Trump is somebody who is so used to litigation and has lived so long in courtrooms that he knows to throw in some aspect of deniability. Just think of the very famous ellipse speech where he is-- it's a rallying cry, but then he says, and go peacefully. He obviously didn't mean that. You know he didn't mean it because after they don't go peacefully he's all in favor of it and doesn't do anything for hours to prevent it.

I think to my mind, if I were prosecuting him, I would use that language to show that he knows exactly where the line is. He knows exactly what makes this criminal and not and he's trying to throw something in so he has deniability so he can say, "Look, you see, that's not what I was intending," even though the whole import of what he is saying is criminal.

Brian Lehrer: All right, now we'll make the segway to the January 6th Federal Special Counsel investigation with Richard, a lawyer calling from Brooklyn. Richard, you're on WNYC with Andrew Weissmann. Hello?

Richard: Good morning. My question is, while I'm happy that Jack Smith has been appointed special prosecutor, he appears to be going full speed ahead investigating the coup attempt. It's infuriating that took the DOJ under [unintelligible 00:34:34] a year and a half to two years to really get started looking at the higher-ups versus the low-hanging fruit.

I want to ask Andrew, to what does he attribute the hesitation? Is it that Garland is such an institutionalist? Is it that he wants to restore faith in the Department of Justice after the travesty that was [unintelligible 00:35:00] What is behind this infuriating hesitation to go after the higher-ups?

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Richard. Andrew?

Andrew Weissmann: I love this question. I agree wholeheartedly with that concern. When the reports broke in the last couple of days about the fact that Mark Meadows was subpoenaed to the grand jury, I think a very natural reaction of people is, look, are you kidding? Now? Yes, of course, he should be. If there's anyone who's going to have information that's relevant to looking at Donald Trump and others it's going to be the Chief of Staff. Yet how many years is this after January 6th itself? There's no question that there has been delay.

What it's attributed to is somewhat speculative on everyone's part. I do think that it is in part what you're saying, which is that Merrick Garland came in with this whole idea of trying to have the department be depoliticized that it is independent of the White House, which is so important to the rule of law that I think he thought that this was an area that he would keep his head down and he didn't need to look backwards, he could just look forward. He might be able to just go after the people who participated on the day of January 6.

I think that was totally wrong and I don't think that is depoliticizing. I think that is an abdication of one's duty in a case where it's so against the rule of law to go after foot soldiers, but not the people who ordered it. I do think they are where they need to be. Unfortunate is not even the right adjective, but it is unfortunate that it took so long. I do have full confidence now in Jack Smith and in the Department of Justice that they are focusing on this and that they are going to proceed responsibly and tenaciously.

Brian Lehrer: Another Merrick Garland question from Joel in Newark. Joel, you're on WNYC. Hi there.

Joel: Good morning. Good morning, Mr. Weissman. Your previous caller just made reference to the time delays and pursuing the insurrection charges. I want to ask some questions about the operations of the grand jury. With this particular grand jury, they already have an outline of the statutory provisions that the Congressional Committee gave, so they don't need Mr. Smith to describe exactly what statutory provisions to indict on.

Supposing they voted out an indictment, and either Mr. Smith or Mr. Garland did not want to pursue it, what would be the legal actions that would be taken? Could something be sealed and strung out forever? Could, say Mr. Pence make appellate appeals which would delay the thing? When would it become public if something like that happened? That's my question.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Joel. On the scenario that he lays out, Andrew, the premise, I guess it's possible that the special counsel, Jack Smith, could recommend a criminal indictment against Trump or any other senior former official, and then it's still up to the Attorney General, even though there is a special counsel, whether to actually file the charges. Right?

Andrew Weissmann: Yes. Those are two slightly different things, but one is whether the grand jury could indict, even though the Department of Justice, whether through Jack Smith or Merrick Garland, didn't want to proceed. That question, which I think is what I heard, I think that the Department of Justice would say that they, as the executive branch have the exclusive right to decide whether to go forward or not. I think they probably would be vindicated by the courts on that. It would be extremely unlikely. I have never heard of that situation arising where you have that.

I think what could also happen is, Brian, is what you're raising, which is, what if Jack Smith wants to go forward with indictment, but the Attorney General says no? It's important to know that Jack Smith, although he's called a special counsel, is within the Department of justice and is subject to, at the end of the day, any and all rules that the Attorney General wants to create and impose. Having litigated this a number of times when I was working for special counsel Mueller. The reason this special counsel provisions work is because the special counsel is what's called a subordinate officer, meaning subordinate to the Attorney General. Merrick Garland would have the ultimate call. If he thought that the indictment was not appropriate, either because it was insufficient proof or the crime being considered was not something the department usually would prosecute with respect to anyone else, he would have the ability to say no.

On the latter, I would say that the crimes that we're talking about, it's really hard to see how this dug would not fit within the Department of Justice precedent. Meaning that there would be lots of things you could point to, to say anybody else would be charged with this. For instance, on the January 6th crimes, we have all sorts of low-level or lower-level foot soldiers who are being prosecuted. It would be hard for a leader of the coup to say, "I shouldn't be charged because people aren't normally charged for that."

Same thing for the Mar-a-Lago mishandling of classified information. There are lots of low-level people who are prosecuted in situations that are far less egregious than what appears to have happened in Mar-a-Lago.

I think it would be very hard for Donald Trump's defense counsel to argue that he shouldn't be prosecuted because it's a form of selective prosecution.

Brian Lehrer: Just one more federal investigation question and then we're out of time. The names coming out about who the special counsel in the Justice Department is calling as witnesses, including former chief of staff Mark Meadows believed to be a key architect of the coup attempt, and Mike Pence, seen of course, as a victim of it, but Pence apparently says he won't testify. What's going on there?

Andrew Weissmann: There's both a political element and a legal element. The political element, that's not really within my bailiwick, but lots of people have talked about how this is a way for him to try and thread the needle to ingratiate himself with so-called MAGA Republicans. It remains to be seen whether that could really work. On a legal front, this is a novel issue. The idea that the vice president has this dual role, they're part of the executive, but at times they have a limited but some role in the congressional sphere.

He's raising the speech and debate argument. The one thing I would say on that is, even if he were right legally, and lots of people including Laurence Tribe think that he's dead wrong. Even if he were to prevail legally, it would only preclude a very small portion of his testimony. There are lots of areas about what Donald Trump allegedly did that the former vice president would be able to be asked about.

Such as, "Mike Pence, did you think that you had won the election and tell me about your conversations with the former president about that?" There is nothing about that that would be covered by the speech and debate clause.

Brian Lehrer: Andrew Weissmann was general counsel to the FBI, and he was the lead prosecutor in Robert Mueller's special counsel's office in the Donald Trump-Russia investigation. He's the author of Where Law Ends: Inside the Mueller Investigation and he is a professor of criminal and national security law at the NYU School of Law. Andrew, we always learn a lot when you come on. Thank you very much for spending this time with us today.

Andrew Weissmann: I love being here. Thanks so much for inviting me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.