The Life of Frederick Douglass

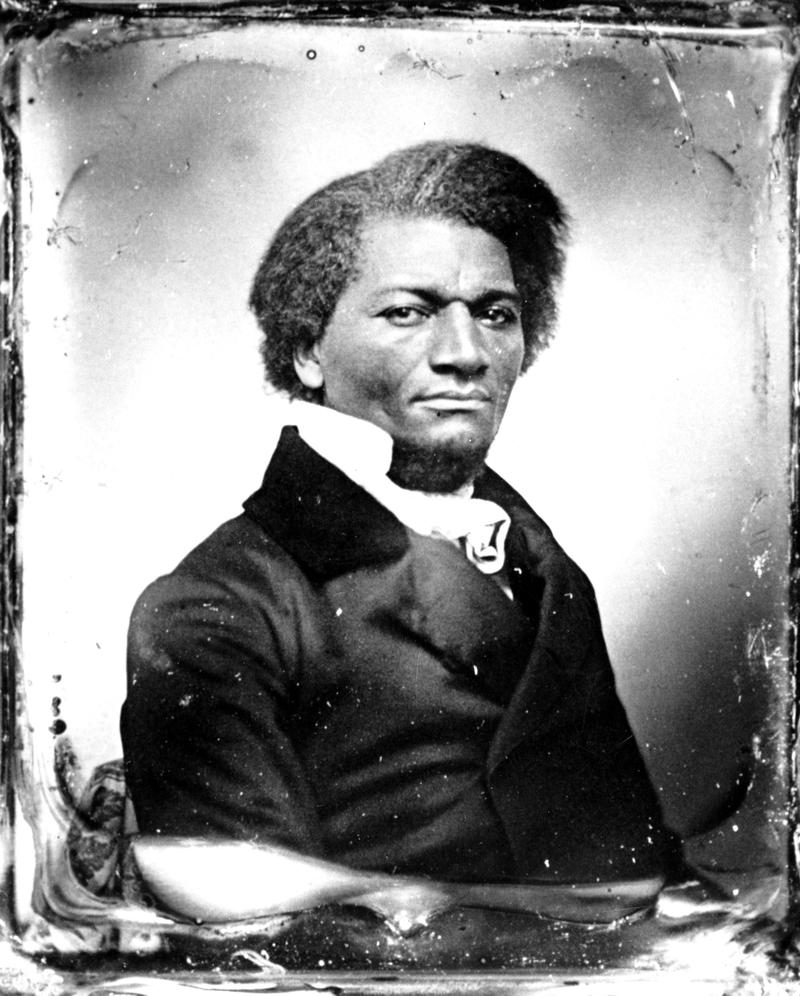

( ASSOCIATED PRESS )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC, and now Brian Lehrer Show history segment but with a weird modern day prelude. Among the many baffling things that President Trump and his appointees have said, came the time that President Trump and Sean Spicer seem to suggest that the 19th century African-American icon Frederick Douglass is alive today.

Donald Trump: Frederick Douglass is an example of somebody who's done an amazing job and has been recognized more and more I notice.

Brian Lehrer: That was Trump in February 2017 as he celebrated the opening of the National Museum of African-American History and Culture at the Smithsonian which is, of course, shut down right now but that's another show. When Press Secretary Sean Spicer was asked to clarify what Trump meant, he reinforced the impression. This begins with a reporter's question.

Reporter: When he made the comment about Frederick Douglass being recognized more and more, do you have any idea what specifically he was referring to?

Sean Spicer: Well, I think there's contribution. I think he wants to highlight the contributions that he has made, and I think through a lot of the actions and statements that he's going to make, I think the contributions of Frederick Douglass will become more and more.

Brian Lehrer: For the record, Frederick Douglass is believed to have been born in 1818 and he died in 1895. Whether Trump knew who he was, the government did create a Frederick Douglass Bicentennial Commission to honor the 200th anniversary of his birth last year. Just this week, on Wednesday, Trump signed into law a bill passed by Congress called the Frederick Douglass Trafficking Victims Prevention and Protection Reauthorization Act. It's an anti-human trafficking bill sponsored by New Jersey Congressman, Chris Smith. Maybe Trump is eager to single out Frederick Douglass for praise because as Douglass biographer, David Blight has said, "Modern day conservatives have appropriated Douglass' advocacy of self-help to claim him as a voice of limited government when nothing could be further from the truth."

David Blight's newest Frederick Douglass book was named one of the New York Times 10 best books of 2018. It's called Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. David Blight is director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale; and he joins me now. Professor Blight, it's an honor. Welcome to WNYC.

David Blight: The honor is mine, Brian. Thanks for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Before we get into some of the book content, what did you mean by modern day conservatives appropriating Frederick Douglass? What's the Douglass reality there and what's the distortion?

David Blight: Well, the right wing in this country has been doing this for a long time. They particularly point to Douglass' frequent advocacy of Black self-reliance in the 19th century. He did indeed advocate Black self-reliance. He often said in answer to the question, "What shall be done with the negro?" He would say, "Let him alone but give him fair play." What modern conservatives have done, from Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas to the Cato Institute in a recent book called Self-Made Man to many others, including Black conservatives I must say, is they go into that part of Douglass' thought, they pluck it out of time and context. And they say, "You see. Douglass was a rugged individualist who believed in self-help and bootstrap philosophy."

To do that is to ignore I would say perhaps at least 90% of the rest of Douglass' life and thought. It is to ignore his long work as a radical abolitionist, and particularly, it ignores that Douglass always and everywhere advocated energetic activist interventionist use of federal power to destroy slavery, to try to defeat the Confederacy, and to establish civil and political rights for African-Americans.

What modern conservatives have done is to try to take the greatest Black spokesman of the 19th century and one of the greatest of all of our history and appropriate him for their cause and their side. It's what we've always done with Lincoln. It's what we tend to do with Martin Luther King. Any major figure in American history will be appropriated like this, but when the past does get misused, we have to say so.

Brian: Do you have any idea if that's what was on Trump's mind, this idea of Frederick Douglass and Black self-reliance when he implied Douglass is alive today and being recognized more and more, or would that be total speculation?

David: It'd be total speculation. I have no idea what's on Trump's mind. All we can say is that that statement did two things. It demonstrated the significance of presidential ignorance, but it also opened up a swath of space for us to try to then educate. It is amazing. I've been giving dozens and dozens and dozens of book talks around the country about this book. I've lectured on Douglass for years. Everywhere I go, this particular Trump quote emerges somehow from the audience in some way or form. Usually, in some sort of humorous way.

Also as a way of saying is it possible that large swaths of this country still don't even know who Douglass is? The answer to that is probably yes.

Brian: To give our listeners a sense of the enormity of Frederick Douglass in his lifetime, you write that he was probably the most photographed American in the entire 19th century. He wrote three autobiographies that became instant classics, and it's likely that more Americans heard him speak than any other public figure of his time. Can you give us a sense of how an African-American would have been the most seen speaker of that era?

David: Yes. It has to do, first of all, with his genius as an orator. His public oratory career begins in 1841 and it will last more than 50 years. He traveled thousands of miles. It's impossible to actually calculate any exact number, but the only American who probably traveled more distance than Douglass as an itinerant lecturer is probably Mark Twain, and Twain went to Asia so it changes the game. Douglass was always on the road, whether it's during his abolitionist career down to the Civil War or his post-war 30-year career of lecturing and traveling and speaking. Sometimes as just a hired Chautauqua speaker and sometimes as a political speaker in election campaigns for the Republican Party.

He probably reached more people in his audiences than any other speaker of the 19th century. Along with that, of course, came all of the both pleasures and perils of fame that go with being such a noted public personality. It needs to also be said that he had, from an early age, a genius with words, a genius with language. He could find in metaphors, he could find in explanations, he could find in his storytelling, which was often rooted in biblical story, ways of capturing what Americans were feeling, experiencing, doing, whether they agreed with him or not; and it is why I put the word prophet in the title of this book.

It took me some time to get the confidence to do that, but he did have that quality of a prophetic voice. That capacity to find the words to explain both catastrophe and triumph, to explain pivots in history, to explain the meaning of events, to explain an idea like slavery, an idea like freedom, as well if not better than anyone else in that century.

Brian: Your book focuses mostly on the last third of Douglass' life, from the years right after the Civil War through his death in 1895. Well, I'm curious if the content or emphasis of his speeches evolved much as he got older.

David: It did indeed. They changed a great deal. I focus on the entire life, the entire trajectory of his 77 years. He lives most of the 19th century, but I became especially fascinated with that last third of his life, the older Douglass that people tend not to know much about. If Americans know Douglass, it's probably because they've read his first autobiography in school and they know about the heroic Douglass. The Douglass who overcame slavery, who became the famous abolitionist, who then became the great advocate of emancipation in the war.

After the war, he became a political analyst. He became the old radical outsider who became a political insider. He became a federal bureaucrat. He became a functionary in the Republican Party, but he continued to lecture on every subject from his famous speech called Self-Made Man to another famous speech called The Composite Nation which was really a very modern imagined idea of a multicultural, multiethnic America to every king of racial issue in American society, from violence and terrorism to lynching to the Kansas Exodus.

He was always, always preaching to his audiences about the power and significance of America's creeds, of the natural rights tradition, first principles of the Declaration of Independence. Above all, in those last 30 years, he was always preaching to his audiences the significance of the triumph of the Civil War and the remaking of the nation through the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments. He was always trying to hold on to his own abolitionist memory of that great pivotal event of the century, the Civil War.

Brian: It's Brian Lehrer show. History segment on WNYC with David Blight, director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale. His book named one of the best 10 books of 2018 by The Times is Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom.

You just said that Douglass had become a functionary of the Republican Party. Of course, that was the party of Lincoln at that time, but you're right about Douglass seeing the Republican Party retreat from the egalitarianism of reconstruction to become the party of big business. Can you describe a little of how the Republican Party changed in the last decades of the 19th century, and how Frederick Douglass responded to that publicly?

David: Sure. It became a big dilemma for him because the Republican Party for him was not just the party of Lincoln. It was the party of emancipation. It was the party that had preserved and saved the union. It was the party of Grant. He campaigned vigorously for Grant in 1868 and 1872, but that party does change. Into the 1870s, as Northerner's retreat from their support of the reconstruction policies, and governments in the south, these white Southern democrats take back control of the ex-confederate states, establish white supremacist regimes.

That Republican Party began to backtrack. It indeed became, by the Gilded Age, the late 1870s and into the ‘80s, a party of big business, a party that argued mostly for the great railroads at the steel companies, and then like a party that became rather anti-labor. It was difficult for Douglass to continually shoulder up to the Republicans, but he did nonetheless. One of the most fascinating parts of Douglass’s story is how does this old radical, when he becomes a political insider inside the Republican Party, how does he cope with that? How does he sustain that? How does he defend that?

The truth is sometimes he had a very difficult time defending them but he always said, “The Republican Party is the ship, all else is the sea.” There really was nowhere else for Black voters where they could vote to go than the Republican Party because the Democrats became a fiercely white supremacist organization. They always had been, but they became more so by the 1870s and 1880s. To his death, Douglas campaigned for every Republican candidate for president from Lincoln's re-election in 1864 to the election of 1892.

It was a difficult dance and he took a great deal of criticism from the next generation, particularly Black leaders who wanted to develop some new fusion politics or tried emerging third-party movements. It's a very modern dilemma. It's a dilemma we've seen in our own lifetime, we've seen in our 20th century, history over and over and over. How do you sustain a political persuasion, a party, a loyalty when that definition of that party changes over time?

Brian: Listeners, do you have a question for historian David Blight, author now of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom 212433 WNYC 433962. Our conversation will continue in a minute.

[music]

Brian: Brian Lehrer on WNYC with Yale historian, David Blight, author of Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom, named one of the 10 best books of 2018 by The Times. He’ll be doing some in-person appearances if you're interested, including at the John Jay Homestead in Katonah next Thursday evening, January 17th at 6:30. He'll be at the Chapin School on the Upper East Side in Manhattan on Tuesday night, January 29th at six o'clock, and at the St. Paul's Chapel of Trinity Church on Tuesday, February 5th at seven o'clock. David Blight coming up in Katonah at the John Jay Homestead, at the Chapin School, and at Trinity Church. We'll put those on our website if you want to look ahead to some of those dates.

Professor Blight, the subtitle of your book as you've just referred to is Prophet of Freedom. You write that Douglass’ words, among many other things, captured the multiple meanings of freedom. I'm curious what you mean by multiple meanings of freedom according to Frederick Douglass.

David: Well, what I mean by that is, in his writings, his voluminous writings, and he wrote millions of words, he talked about the meaning of freedom of the mind, of the body, and of the soul and the spirit. He wrote endlessly about what slavery actually could do to a human being, what it could do to your body physically, but especially what it could do to your mind. What humiliation can do to the soul, how the constant denigration of slavery could in effect ruin the spirit. There's a little line in his first autobiography where he's remembering being a child.

Of course, he's writing this as a 27-year-old adult, but he's remembering being a child and he remembers standing out under the trees of the Wye plantation or when he's in Baltimore and just asking himself, “Why am I a slave when these other little white children are not? Why am I a slave?” Then he goes on to reflect what that means for his mind, body, and soul. When one reads that, there's a reason why that first autobiography, the narrative, has become a worldwide text.

There's a universality in that because anyone can read that from wherever they sit on the planet and say, "Well, it's no different than why those people in that other valley hate us, or why those people of that other religion attack us, or why those people who speak that other language don't like us, or why I'm so judged for my sexuality, or why I'm hated for my race or my ethnicity." It's the same question. Why am I hated as a Syrian refugee child? Why am I hated as a Mexican refugee child? There's a universality in the way Douglass wrote about, talked about, the meaning of having been a slave and then achieving adult freedom and the intellectual capacity to analyze it.

Brian: He was an early male supporter of women getting the vote, wasn't he?

David: Oh, indeed. He was an early women's suffragist. He was the only male speaker at the famous Seneca Falls Convention of 1848. At that point, he lived in Rochester, New York. He had just moved there. He had just founded his own newspaper only about six months before that Seneca Falls Convention occurred. He went back and changed the Masthead on his own newspaper, which was called the North Star to the slogan "Right is of no color or sex". He even advocated the equality of women's economic rights, which meant the right to own property, the right to divorce, and so on and so forth. He ended up having a huge falling out as many people know.

Later in 1869 and '70 over the 15th amendment, that falling-out was with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B Anthony, and other leaders of the women's suffrage movement because the 15th amendment only applied to males and only to Black males in terms of franchising the former freedmen. The women suffragists were just no longer patient enough to wait. The trouble was they attacked Douglass and they attacked Black men with exceedingly racist language that caused a terrible at least temporary break-up between Douglass and the leaders of women's suffrage, parts of which were never really repaired.

He was always consistent in advocating the Black women should have the right to vote. He just knew as everyone else knew in 1868 when the 15th amendment was voted that if you put women's suffrage into that amendment, it simply never would have passed.

Brian: We just have a few minutes left. You do also write about Douglass’s private life, including some struggles with the extent of his fame, including that his second wife was white, and that he had children and grandchildren who were relying on him for financial support. Was it a source of conflict for him internally or in his communities that he married a white woman?

David: Oh, yes, indeed. I read a great deal about Douglass' private life. You have to. That's the craft of biography. He did marry twice. His first wife, Anna, of 44 years was a born a free Black woman who followed him out of slavery. She remained largely illiterate all of her life and when she died in 1882, a year and a half later, he married Helen Pitts, a very well educated woman with a degree from Mount Holyoke College, who was 20 years younger. He was 66 and she was 46.

It was the most scandalous marriage of the 19th century, bar none. The press coverage went on for months and months and months in Black papers and white papers. He was largely condemned in the Black press, although not entirely, and not entirely in the white press either. There were those people who said, "Look, the man should be able to marry anyone he pleases. It's his human right," which was his response always to this question, but it caused great difficulty for his four adult children.

His daughter Rosetta, his oldest who was just about the same age as Helen and his three sons, they always said the right things publicly but they never warmed up to Helen; but by all accounts, it was a very good marriage. The last 11-12 years of Douglass's life, he had a very comfortable and much more public marriage with Helen Pitts. They even did an 11-month tour of Europe and the Mediterranean together in 1886.

Brian: We just have 30 seconds left. Being the prolific writer and influencer that he was, do you ever fantasize about how we might have used Twitter or Instagram?

David: Do I fantasize about that? No, frankly not, because I don't do Twitter or Instagram. Maybe I would if I did.

Brian: Or even radio and television, which we're after him.

David: Oh, well, now that's another matter. Douglass would have been a tremendous US senator and he'd have been on every night on cable television telling the country what he thought about this policy or that policy. He'd had been a media-- He was a media star in the 19th century. He couldn't go anywhere without being recognized. He had paparazzi who followed him wherever he traveled by the latter part of his life.

Brian: I have to jump in there and leave the rest for people to read your book. That ends this Brian Lehrer show history segment. David Blight's newest Frederick Douglass book, his third, was named one of the New York Times' 10 best books of 2018. It's called Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. David Blight is director of the Gilder Lehrman Center for the Study of Slavery, Resistance, and Abolition at Yale. Thank you so much.

David: Thank you, Brian, very much.

Brian: Have a great weekend, everyone. Brian Lehrer on WNYC.

[music]

[00:23:03] [END OF AUDIO]

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.