Evaluating New Jersey's Bail Reform Model

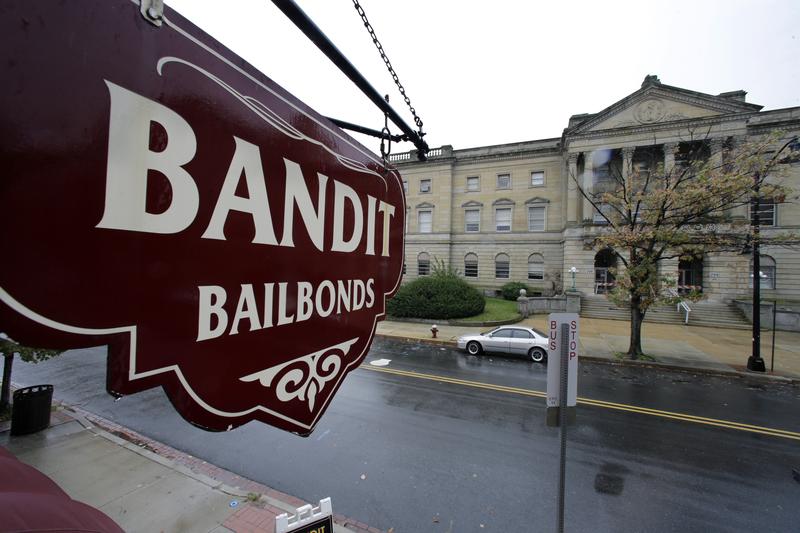

( Mel Evans / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. We've been inviting you to take Mayor Adams up on his suggestion to read for yourself his Blueprint to End Gun Violence and post a comment or a question about it with the #ReadTheBlueprint. Remember the mayor said this when it came out.

Mayor Adams: Read the plan. My plan cannot be defined on a tweet, it's defined by picking up the document and reading it.

Brian Lehrer: It's very short. It's 15 pages of large print, clearly sectioned, minus even the cover page and the Table of Contents page. It's a quick read, and read the blueprint. #ReadTheBlueprint. We will spend the first full hour of Thursday's show discussing the blueprint. See the link on our Twitter feed to the blueprint or our website at brianlehrershow.org. The hashtag for comments again is #ReadTheBlueprint.

We've also been digging into specific aspects of it in recent days. As most of you know, one thing the mayor wants is for judges to have discretion to detain defendants on gun charges as well as other things before trial on grounds of dangerousness as assessed by a judge. On this show, the mayor said data could help prevent judges from seeing dangerousness based on biased perceptions by race.

Mayor Adams: I know, based on the failures of the past, how our criminal justice system was unfair, was biased, in some cases, it was racist. What we must do is use the data on those judges that are not fairly using the dangerousness standards to retrain them or to use my power as appointing criminal court judges to determine they're not suitable to sit on a bench.

Brian Lehrer: Mayor Adams here the other week. Well, as bail reform remains a contentious issue in New York, it seems to have been settled, at least for now, in New Jersey. A 2017 law in the Garden State abolished bail altogether, New York has not done that, but set up that discretion for judges based on dangerousness as measured by specific data points. Some say New Jersey is a good model for New York to learn from. Let's take a look.

With me now, Elie Honig, some of you know him as a CNN legal analyst and author of the book Hatchet Man about Donald Trump's Attorney General William Barr. He was here for a book interview on that. Elie Honig was also the director of New Jersey's Criminal Justice Division and oversaw the implementation of the new bail reform system when it took effect five years ago, and he just wrote a piece on nj.com recently called New York please Read This. Your bail reform is in trouble because you're making 2 big mistakes.

Also with us, Alexander Shalom, senior supervising attorney and director of Supreme Court advocacy at the ACLU of New Jersey. Elie, welcome back. Alexander, welcome to WNYC.

Elie Honig: Hey Brian, thanks for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Elie, would you explain the basics of New Jersey's 2017 bail reform law and how it's different from the 2019 bail reform in New York that the mayor wants to revisit?

Elie Honig: Yes, absolutely, Brian. For centuries, New Jersey had based bail on cash. A person would get arrested, go in front of the judge, and the judge would say, "I hereby set your bail at X amount." The only thing that judges were technically allowed to consider in New Jersey was the risk of flight. The risk that this defendant would take off, become a fugitive, not come back to the court and, importantly, not dangerousness. Prosecutors were not allowed to stand in front of a judge and say "He's too dangerous, we need to lock them up." Judges were not allowed to consider that.

Now, there were two big problems with this system. One we had thousands upon thousands of low-level, nonviolent arrestees who were stuck behind bars for months leading up to trial, waiting for trial, not yet adjudicated guilty. Two, the system did not allow us to lock up without bail the most dangerous offender. If somebody was charged with a double murder but could post the money bail, he could get out pending trial. We fixed that system.

As you said, Brian, we essentially all about got rid of cash bail and we switched over to a database risk assessment system. We can talk more about the results, but it's been a success really based on almost any metric that you look at and we're now four, almost five years into it.

Brian Lehrer: Well, of course, we will talk about the results. Listeners in New Jersey, we want your comments or questions about the no-bail, yes-dangerousness standard system that's been in effect in the Garden State for the last five years. 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Any lawyers in New Jersey or judges in New Jersey or defendants past or present, or crime victims, or anyone want to weigh in with your own experience, 212-433-WNYC. Help New York learn from New Jersey's experience.

Anyone with a question, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer. Elie, what are two big mistakes that New York is making that you referred to in your nj.com headline?

Elie Honig: I want to say, first, I applaud the effort and the impetus behind New York trying to do this. In fact, when Alex and I and others were doing this in New Jersey, we actually went up to New York and met with leaders in New York to give them our advice. They took most of it, but not all of it. The two problems that I see with New York system; one, they do not allow judges to consider danger, they're still stuck in this mode where the only thing judges can technically consider is, "Is this person a risk of flight? Is this person likely to appear or unlikely to appear?"

In New Jersey, like I said, we changed our law. We actually amended our state constitution, which was an arduous process, to allow judges to consider danger. The second thing is, the New York law has this long list of automatic release crimes, where if you're charged with these crimes, you automatically get released. Now, some of them are what you'd expect, your petty stuff, and that's fine, very low-level drug cases.

Here's just a sampling of some of the offenses that are listed on the automatic release list that I think are huge problems and endemic of the problem here. Second-degree manslaughter, stalking, assault as a hate crime, grand larceny, aggravated assault on a child under 11 years old. That's just a sampling, but this automatic release list of offenses is way too long, way too broad, and way too permissive.

Brian Lehrer: Before we bring in Alexander Shalom from the ACLU and see if he disagrees, because I know the New York Civil Liberties Union is very against the dangerousness standard. How is dangerousness measured by judges in New Jersey? Using what data to cite Eric Adams' promotion of the use of data to prevent judicial bias?

Elie Honig: We use an algorithm. We have an algorithm that geniuses at the Arnold Foundation, which is part of NYU, developed for us, which they had tested over tens of thousands of real-life cases. Whenever someone gets arrested, they actually get two scores, one to six. One is low, six is highest on risk of flight and on dangerousness. The factors that go into those scores, the dangerousness score are essentially the person's prior record of convictions, of violent convictions, the nature of the current offenses. It's all objective, there's no subjective judgments, it's just, has this person previously been convicted of a violent offense? Yes, no. How many? One, two, three, whatever.

Then the system spits out a score. This is really important, Brian, because I know people are a little bit skeptical of these numbers. They don't want to end up like that movie from the '90s Minority Report with Tom Cruise where they're arresting people for future crimes. That's a dystopic view of this. There is the data system, but it's not binding. Everyone who's involved in the system, prosecutors, defense lawyers, judges, gets to start from there, but then make their arguments and use their judgments. I think it's a nice blend of the analytical, but also the classic judgments that you'd see in a court.

Brian Lehrer: Let's bring in now Alexander Shalom, senior supervising attorney, and director of Supreme Court advocacy at the ACLU of New Jersey. Alexander, I understand that the New Jersey Civil Liberties Union Chapter was involved in development of this bail reform, along with stakeholders from law enforcement and others. How much was that the case? How much did your group, does your group, approve of the law as it stands?

Alexander Shalom: Hi, Brian. The answer is we were intimately involved in the creation of it, but I think it's important to contextualize where we were coming from and why we were so involved. As Elie, I think, noted, the system that we were replacing was a deeply flawed and deeply broken system, where the size of your wallet dictated your freedom. We recognized how fundamentally unfair that was, and we also recognize the pernicious impact it was having on people, coercing plea bargains and ruining their pretrial liberty.

We helped, with Elie and his colleagues and many other community organizations, build a system that we thought was far better than the one it replaced. That doesn't make it a perfect system and we've never pretended it was, there are still deep flaws in it. I think, fundamentally, the idea of pretrial incarceration is in deep tension with our belief in the presumption of innocence. These are people who have not been convicted and so it's a system that's very challenging for us but it's a system that we do think is a vast improvement. Just to quickly correct one thing that Elie said or refined one thing he said, the risk measurement that we use doesn't actually evaluate a person's dangerousness, it evaluates the risk that the person will be rearrested while on pretrial release.

Look, sometimes that says something about the person, but oftentimes, it also says something about the police. The act of being arrested takes two to tango here and we know that there are deep disparities in what police do. I think people who talk about the fear of disparities in the system have lots of data to support that because we know that certain communities are more likely to be arrested than others. Again, going back to your original question, this is a system that is a vast improvement over the one that it replaced, though still far from perfect.

Brian Lehrer: Well, you mentioned police bias, what about judicial bias, where the presumption of many people and with hundreds of years of experience to back this up, is that judges, as a group, who are likely to disproportionately see Black people and other dark-skinned people as more dangerous than white people who've committed the exact same things and have the exact same backgrounds?

Alexander Shalom: As Elie said, and I agree with him, by almost any metric, the New Jersey system has been a rousing success. The one metric on which it has admittedly not been a success is in reducing racial bias. It hasn't increased racial bias, because I think the old system also was deeply embedded with racist decision-making, but we've seen the same rates of disproportionality in the pretrial incarceration of people of color as we did before, and that's troubling. I think people who look to New Jersey as a model have to grapple with that. It's inescapable.

I do think, if I can, one of the common threads between New York and New Jersey here is this talk that Mayor Adams is doing about data, but I actually think he has the acquiesce wrong. What I would say is, if what he's saying is, "Look, we need to fix New York's bail law because gun violence is out of control, or because violent crime is rising," well, then we have to actually say, "Well, but is the New York's 2019 bail law to blame for increased gun violence?"

We're having the same conversation, frankly, in New Jersey. Elie is mercifully, for his sake, out of New Jersey politics now, but we're seeing the same thing where people are saying, "Oh, wait, gun violence is increasing in some of our cities. We have to change our bail law." The problem is if you identify the wrong cause of the problem, you're also going to identify the wrong solution. That's what we're seeing in New Jersey. I fear that's exactly what's going on in New York, which is, let's not blame the bail law when we see increased gun violence in cities across this country, those that have had bail reform and those that haven't, those that have democratic-- after you.

Brian Lehrer: Elie, Alexander is saying this system in New Jersey is not as big a success as you claim, because the very thing that New Yorkers in the state legislature are resisting that Mayor Adams wants, imposing this dangerousness standard at a judge's discretion, Alexander says not working in New Jersey, there's still racial bias at the same levels as before, from the bench. That means people getting locked up who shouldn't be locked up.

Elie Honig: A couple of things on that, Brian. Bail is far too complex to ever offer a perfect solution. What you are doing is you are releasing people who've been charged with crimes, you are releasing thousands upon thousands of those people. There are going to be several them who get locked up again, there's just no way around that. I agree, it's not every single thing has been a success.

Let me take two points here. First of all, on the notion that racial bias has not been lessened by this, one of the hopes of the data-driven system is that we would impose some consistency, some common fence posts so that all judges across the state could see this number 123456, the risk score or as Alex said, actually, more precisely the risk of re-arrest score, and at least be operating from the same page.

Where you go from is up to you, bail reform can't control that. I will note this though, our statewide pretrial incarceration numbers are way down in a good way. This is something, even as a prosecutor, I was very much in favor of, pushed for, and I'm proud of now. Essentially, from the time we started this, the beginning of 2017 till now, our pretrial incarceration population is down 20% and change, and the vast majority of those people who are out now who would have been in because they couldn't post very low bails are Black and other minority arrestees.

I think that's a good thing we are now incarcerating fewer people and fewer minorities. I also do want to say, let's be very careful. I completely agree with Alex on this. Let's be very careful of bail reform just becoming a boogeyman essentially, where we say, "Oh, everything wrong in the streets, everything wrong with the system, blame bail reform." It became a joke candidly in my office because everyone was blaming bail reform for everything, even if it had nothing to do with bail reform. The air conditioning would go out in the office, and someone would jokingly say, "Oh, it's bail reform's fault."

Let's be very careful what we are attributing to bail reform and what we are just blindly throwing up against the wall and saying, "Blame bail reform."

Brian Lehrer: Are you saying that the numbers in New York do not bear out that the bail reform that got instituted in 2019 is contributing to the rise in crime?

Elie Honig: Well, no, I'm not saying that at all. I'm not defending New York system or defending New Jersey system. What I would want to note though is not just what's happening with crime rates, but how much of that can be attributed to people who've been released on bail. If there's data showing that some percentage of the crime is attributable to people who've been released and that's more than before, then I will be convinced by that.

I do think the data has a story to tell here, but it doesn't necessarily tell the same story in New York and New Jersey. We took a very hard line in New Jersey on firearms crimes early, and I don't mind telling you, we didn't get it exactly right. Our bail reform went into effect January 1 of 2017 and five or six months in, I was at the AG's office, we realized, well, too many firearms offenders are getting released and that's not a good thing.

We changed our guidance to prosecutors and police across the state and said, "You need to be seeking detention more aggressively," and the judiciary, our judges, agreed with us and went along with that. You don't have to hit it perfectly the first time. There is room to amend, to tweak. We've done it in New Jersey, I think, effectively. New York, I hope can do the same.

Brian Lehrer: This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York, WNJT FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are in New York and New Jersey public radio definitely being the connective tissue between the two in this segment as we're looking at whether New Jersey's bail reform law, enacted in 2017, can serve as a model for reform in New York as some people say it can, with Elie Honig, who you may know as a CNN legal analyst, but he was also the director of New Jersey's Criminal Justice Division in 2017 when this was getting instituted. We have Alexander Shalom from the ACLU, New Jersey Chapter.

Dino in Paterson, you're on WNYC. Hello, Dino, thank you for calling us.

Dino: Hello. Let me just pull over one second because I was driving. Like I said to your call screener, Brian, I'm older than her, I can tell by your voice, I'm older than her. In '85, I left, went to Europe for a month, spent 11 years, didn't come back till '96. The difference I saw in New York was, oh my god, 42nd Street was accessible, it turned into Disney World. We reduced 2,400 murders a year and it went down to 400 and everybody's coming with this new blueprint books, this new we're going to do the gun run retraction, [unintelligible 00:19:18]

Why reinvent the wheel? We know it works. We've seen it in New York. Brian, you know what I'm talking about. Is that correct?

Brian Lehrer: I think that it's complicated, because if crime goes down, but unnecessary mass incarceration goes up, then you haven't solved the problem. Maybe you've solved one problem and created another problem. Also, even as mass incarceration was coming down in recent years, and stop-and-frisk Bloomberg-style was abolished, and the crime rate continued to come down under Mayor de Blasio until the pandemic started. Well, I don't know that we've determined that the lock-them-up-and-throw-away-the-key system necessarily made that difference.

Dino: I'm not talking lock them up and throw away a key. I'm talking saving 2,000 lives a year. Over 10 years, that's 20,000 lives. How many more lives do you want to save?

Brian Lehrer: What are you saying did it? What are you saying accomplished it?

Dino: Obviously, Giuliani, what he did back then accomplished it. The no windows rule. In other words, a small crime leads to a big crime. He was obviously right. Obviously, you could better it a little, that I understand. With the no cash bail, I'm not totally against that, but it's got to be done slowly and see how it progresses. Obviously, what they did in New York is wrong. I agree with them there to look at it. If it's done correctly and slowly, I can understand that.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you. I'm going to go and I'm going to get a response. Thank you very much. Elie Honig, do you want to jump in on that?

Elie Honig: Yes, I do.

Brian Lehrer: He represents the broad strokes conversation that a lot of the media is having, yet I don't think it's that simple.

Elie Honig: Dino, I really appreciate the passion from you. I spoke all around the state to people voicing very similar ideas before, as we were in the process of implementing this. I think, Brian, it's a perfect example of what I said before, how bail reform has just become this scare term for let's blame everything wrong, let's blame all crime, let's blame the condition of Times Square on bail reform. Here's the point I want to make. It's not a question of reform or no reform. It's a question of smart reform that works versus reform that does not work.

I think that's what we're aiming for here. It's not just the question, "Does bail reform work or not work?" You have to look at the specifics, the differences we talked about before between New Jersey and New York. The trick is to find that balance to where you are prosecuting, locking up people who are truly dangerous, truly at risk of recidivism, and you are not though at the same time, locking up thousands upon thousands of low-risk, poor people who cannot post very low money bail.

Let me you about one study that was done in New Jersey that really spurred the bipartisan, I should mention, support for this. We passed this with a Republican governor, Chris Christie, you may remember him, a Democratic state senate, a Democratic state assembly with the support of prosecutors, me, ACLU-- Alex, we don't agree on much, we agreed on this. The study that really galvanized us was a study that showed that 12% of our entire population in this state are incarcerated population. 12% of all the people behind bars were held pretrial, not yet convicted of anything, on money bail of $10,000 or less.

If you're a prosecutor, I was a prosecutor for 14 years, if your goal is to just lock people up on low-level offenses because they're too poor to post a few thousand dollars, you should be in a different business.

Brian Lehrer: Marvin in Tinton falls, you're on WNYC. Hi, Marvin.

Marvin: Hi. My thought is, I'm looking at the new bail reform in New Jersey, it hasn't worked, because police officers are not going out there doing the job that they should be doing because before the paperwork is done, those defendants are let out back on the street to commit other, as you call, low-level crimes such as shoplifting, burglaries. They do it 5, 10 times before a judge finally says enough is enough. There has to be some kind of equilibrium between a cash bail system and the bail reform that we have in its current form.

Brian Lehrer: Marvin, thank you. Alexander Shalom from the New Jersey Civil Liberties Union, that sounds like a challenge to your position.

Alexander Shalom: It is, but unfortunately it's not supported by the crime rates in New Jersey that, since 2017, we've had five years of bail reform and the crime rates have dropped precipitously over that time. Let me be clear, I'm not saying bail reform reduced crime in New Jersey. What I'm saying is people like Marvin who say it increased crime, it's not supported by the data. It's not what the facts on the ground actually show.

We've seen crime reduced, we've seen violent crime reduced. It's true, there has been, in some places, since the pandemic, an increase in some violent crime, particularly with respect to shootings, but that's been true in New Jersey, it's been true in Anchorage, Alaska, it's been true all across the country. There are no criminologists out there who say, "Oh, the recent spike in violent crime gun-based crime is caused by bail reform."

We know the things that increase crime. We know also what the solutions are. If we identify the wrong problem, we're going to identify the wrong solution. Rather than investing in community violence intervention, if we invest in gutting bail reform, changing bail reform, then what we're doing is we're leading to the same problem that Dino talked about of increased harm to communities. If we want to prevent that, we need to be smart and we need to be data-based.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to leave it there with Elie Honig, again, some of you know him from TV as a CNN legal analyst, some of him from his recent book Hatchet Man about Donald Trump's attorney general William Barr, but Elie Honig was also the director of New Jersey's Criminal Justice Division and oversaw implementation of the new bail reform system when it took effect five years ago. He wrote a piece on nj.com recently called New York please Read This. Your bail reform is in trouble because you're making 2 big mistakes.

We also thank Alexander Shalom, senior supervising attorney and director of Supreme court advocacy at the ACLU of New Jersey. Thank you both very much for this conversation.

Elie Honig: Thanks, Brian. The pleasure as always.

Alexander Shalom: Thank you. Take care.

Brian Lehrer: Hopefully, that will inform the debate going on in New York right now. Remember, again, listeners, we've been inviting you to take Mayor Adams up on his suggestion to read for yourself his Blueprint to End Gun Violence and to post a comment or a question about it with a hashtag #ReadTheBlueprint. We have posted a link on our webpage to the blueprint, the webpage brianlehrershow.org.

We've also tweeted it out again this morning. Go read it for yourself, it's only 15 pages of large type and we'll have a larger conversation about the blueprint on Thursday's show. We'll also talk about it tomorrow with the New York state majority leader in the Senate, Andrea Stewart-Cousins.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.