Is There An End In Sight For The Student Debt Crisis

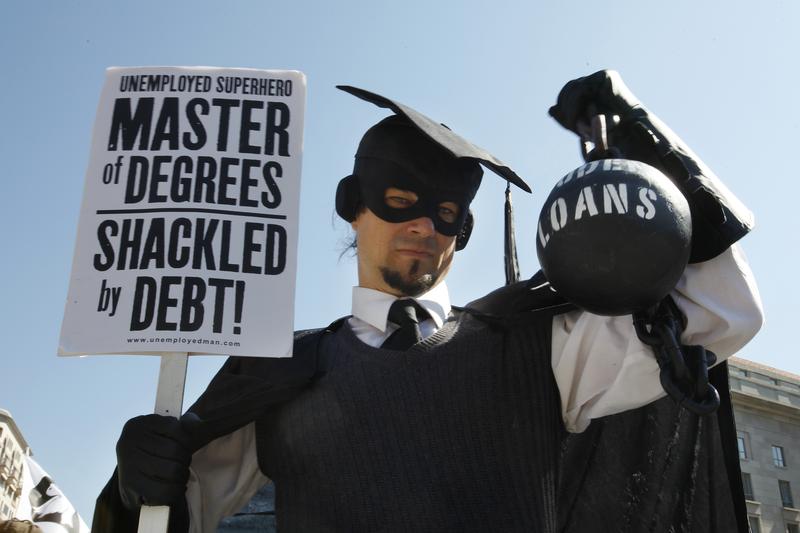

( Jacquelyn Martin / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Earlier this year, the federal government suspended student loan interest obligations because of the economic toll of the coronavirus pandemic, but the CARES Act Relief period that covers that ends on January 1st. That's less than three weeks before Joe Biden would be inaugurated. He was asked this week if student loan debt forgiveness figures into his economic plans. This is how he responded.

Joe Biden: It does figure in my plan. I've laid out in detail. For example, the legislation passed by the Democratic House calls for immediate $10,000 forgiveness of student loans. It's holding people up, they're in real trouble. They're having to make choices between paying their student loan and paying their rent, those kinds of decisions. It should be done immediately.

Brian: Now after that statement, repeating that he would like to forgive up to $10,000 in student loan debt for economically distressed borrowers, his phrase "economically distressed," the criticism came fast. Some said it's not enough. Others said that people with student loans are obviously more likely to have college degrees, which makes them more likely to earn more money, and that debt forgiveness would be unfair because it would be targeted at people already relatively advantaged.

For one perspective, I'm joined now by Sarah Jones, senior writer at the Intelligencer, Intelligencer part of New York Magazine. She's got a student loan article out now with a very straightforward title, "Student loan debt is immoral." Hi, Sarah. Thanks for coming back on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Sarah Jones: Thank you so much for having me.

Brian: What do you make of Biden's position, first of all?

Sarah: It's certainly encouraging to hear that the President-elect views the issue of student debt as such a priority. It does fall short of some proposals that have come out of the Democratic Party to date. For example, there's a proposal from senators Chuck Schumer and Elizabeth Warren that's been endorsed by a number of their colleagues that would forgive up to $50,000 of federally held student loan debt. There's a bit of debate over how much Biden could and should forgive, but it does seem likely that debt forgiveness of some kind is going to happen when he takes office in January.

Brian: Chuck Schumer told an interviewer for a political newsletter called The Ink that he hoped Biden would adopt his and Senator Elizabeth Warren's proposal to erase up to $50,000 in student loan debt. He said he believed the president could do that by executive order, do you ever take on whether that's realistic, either under the law or given Biden's moderate lane that he's trying to carve out in the Democratic Party?

Sarah: On a legal basis, I do think that he has the authority to do this under the Higher Education Act, so it is possible, in my opinion, for him to to actually take up the Schumer-Warren proposal. As you know, he is trying to carve out a moderate lane in the party, but considering the extent of the economic crisis that student borrowers and everyone else is facing at the moment, this really seems like actually quite a pragmatic proposal and not a utopian one by any means.

Brian: Listeners, if you have student loan debt, what do you want President Joe Biden to do about it differently from what President Donald Trump has done about it, and really the Congress, because there is this suspension of at least student loan interest payments, because of the pandemic and the CARES Act that's going to expire in January. 646-435-7280, let's talk about student loan debt. 646-435-7280, with Sarah Jones from New York Magazine, 646-435-7280, or you can tweet a question or a thought @BrianLehrer. How literal and how broad away do you mean the headline of your article "Student debt is immoral"?

Sarah: I mean it pretty literally. When we're talking about the student debt crisis, it's a political problem. It happens because people allowed it to happen. There are political solutions that could resolve it. Debt forgiveness is only part of a package of solutions that would help, but the fact that we've allowed student debt to cumulatively pass over $1.7 trillion in the US, I think that's obscene. It's not like that in other countries, and I don't think that it has to be the case here in the United States, especially when we hold college up as a means to achieve social mobility.

Brian: What's an example from another country that we might learn from?

Sarah: I know in the UK there are caps on how much a university can charge students for attending. I think that's something that we could consider. Certainly, I think that there are ways for us to reform the student loan industry in particular, so that people aren't as subject to predatory interest loan rates. I think that's been a massive problem here, and it's not really the case in nations like the UK and other European countries.

Brian: What do you think the politics of this are? It was very interesting to me that in your article you included some tweets from other people that you included to indicate that there would be a lot of political blow-back to any attempt to forgive a lot of student debt.

Sarah: I do think that we're seeing a bit of a divide here between progressives who have been calling for major reforms to student loan debt for a long time and more conservative economists and other commentators who maybe put more of an emphasis on personal responsibility, or perhaps for ideological reasons as well, don't support some of the more extreme proposals that are coming from the left. I do think the notion that's been raised after Biden and Schumer and Warren have started talking about that forgiveness in a more serious way, are exaggerating the likelihood that there would be significant public backlash.

Brian: One of the tweets that you included from Damon Linkler said, "I think Democrats are wildly underestimating the intensity of anger, college loan cancellation is going to provoke. Those with college debt will be thrilled of course, but lots and lots of people who didn't go to college or work to pay off their debts? Going to be bad." What about those disparities?

Sarah: Those disparities are real, and I don't think it's helpful for progressives, including myself, to minimize them or pretend that they don't exist, but what I said in my piece, and what I still think is correct, is that people that they had to struggle to pay off their student debt, and other people have theirs forgiven, really ought to be angry at the system that put them in debt in the first place.

As for the notions that people who didn't go to college at all might be this as a handout to the elites, certainly it's possible, but thanks in part to phenomenons like degree inflation, where a bachelor's degree is now minimum qualification for jobs in a number of industries. I think that the student debt crisis is more widespread and has broader implications, and a lot of people are giving it credit for.

Brian: Part of the issue is that there are several intersecting crises. How much of the student debt crisis, in your opinion, can be attributed to the college affordability crisis as an underlying reality? In the past 20 years, college costs have ballooned as everybody knows way faster than overall inflation and way, way faster than people's incomes. The cost only continues to go up.

Sarah: I think that's right, when we're looking at this massive number, over $1.7 trillion, that number exists for a lot of different reasons. One of those reasons is, as you note this consistent rise in the cost of tuition and board over time at public universities, but especially private or nonprofit universities. There's also the private student loan industry, which charges predatory interest rates. When we're thinking about student debt, a lot of the debt that people hold isn't even the principal amount that they took out that's interest.

Also, I think you have to consider predatory for profit colleges and universities, because they're an area where people that tend to focus specifically on first generation college students, on students of color, on veterans, people who might not be as familiar with the world of higher education, and they charge extremely high tuitions, and people go into a lot of debt in order to be able to afford those educations.

Brian: Let's take some of the many calls that are coming in. We'll start with Jose in Yonkers. Jose, you're in WNYC with Sarah Jones from New York Magazine. Hi there.

Jose: Hi, Brian. First of all, you're a national hero. I absolutely love you. First time caller, longtime listener.

Brian: Glad you're on.

Jose: I'm just calling because I'm a millennial. I feel like so many of us millennials, we did what we felt was the right thing, what we told was the right thing to do, which was to get in a higher education degree. We were absolutely crushed with the amount of loans that we had to take out to get to that education, bachelor's, master's, whatever it was. Now we're living these menial lives, me and so many of my co-workers and friends, we can't afford anything because we're paying thousands of dollars a month in student loans. Something has got to give. We can't move our lives forward, we cannot really contribute to the American economy because we have these crushing student loans on our back. It's horrible. It's so sad.

Brian: Jose, what would you say to people who might say, "You can't just expect government to wave their hand and forgive loans that you took voluntarily." What would you say to that?

Jose: I think that's tough. I understand that argument. I think, like you were saying earlier, perhaps the problem is the ballooning cost of higher education in this country, which just isn't the case in other developed Western countries.

Brian: You didn't feel you had that much of a choice.

Jose: I think the government should ultimately-- Exactly. I don't feel like I had that much of a choice. I grew up in the South Bronx, I'm a Hispanic. It was my golden ticket out of poverty. I felt like I had to do that and I was doing the right thing. Now I find myself with two degrees, very well educated, and I have to work three jobs just to afford the life that I want to live, and it's crushing. It's horrible.

Brian: Jose, hang in there. We're going to get a response to your story from Sarah Jones in a minute. After we get at least one more on here. How about Alessandro in Brooklyn. You're on WNYC. Hi, Alessandro.

Alessandro: Hey, how's it going? Thank you so much for having me on. I love the work that you've done throughout all these years, you've taught me so much. Thank you so much, Brian.

Brian: Thank you.

Alessandro: I just wanted to get into the point of you asking the question of what sort of strategies can we take right now. I think that the number one thing that we need to get off of our backs are the interest rates of student loan debt. I think it's completely criminal that we are being charged almost 7% for the largest loans that we get from the federal government. I think that this is something that should be completely eliminated for us to really, realistically pay these off. Building on your point, about a $10,000 commitment from the Senate, federal government from Biden's plan to actually put in money to do this. That could be a good economic stimulus, potentially, but you said it's not going to address disparities for

the people who are at most at risk.

I feel like that $10,000 stimulus should be more of a reparation sort of thing in your strategy for addressing African-American Health, addressing Latino health, and people who are experiencing so much of these educational and economic disparities. Give them the $10,000 if anything, if you only have so much money to work with.

Brian: Alessandro, thank you. You and Jose, please, both of you call us again. To Alessandro's point, Sarah Jones from New York Magazine about interest. People are posting some of their own stories on Twitter. One, for example, writes, "I borrowed $80,000 to attend NYU, and I owe $250,000, that is criminal," she writes. What are you thinking after hearing either of those caller

Sarah: Both stories feel very personally familiar to me. These interest rates are a huge part of I called the student debt crisis immoral. It does not have to be this way. It should not be this way. Jose's story, I really resonate with that. My family is not well off. I'm from a rural predominantly low-income area where not a lot of people go into higher education. I really felt like I didn't have a choice. Yes, I took on the loans voluntarily as did Jose, aas did a number of other people, but it didn't really feel like a free choice when my path to financial security was predicated on going to college.

I was not able to complete my education without going into debt. As it stands right now, I will be paying off that debt until I'm 40. I understand where they're coming from, I really do.

Brian: Did the Trump administration do anything, either good or bad? Would there be aspects of this that a Biden administration would have to unwind from Betsy DeVos, or anything like that?

Sarah: There is, and I think that's a really important piece of that conversation. As education secretary, Betsy DeVos did reverse certain Obama-era regulations that crack down on predatory for private, for-profit colleges and universities, which do contribute to the student debt crisis in a really significant way. She's also made it very difficult for defrauded student borrowers to receive debt relief that they're legally entitled to. There have been a number of legal challenges over her failure to process those claims in a timely fashion, and then to grant debt relief, where it's clearly indicated, and evidence suggests that there really should be relief granted in those cases.

The Biden administration could improve the situation, not just by using executive authority to pass some measure of immediate student debt forgiveness, whoever he puts in his education secretary will be in a position to do a lot of good.

Brian: I saw a tweet that said, "There is no such thing as debt forgiveness, and that it would lead to higher taxes." Do you have response to that?

Sarah: I think that's a bit of a strange argument. I have to say, I don't completely understand where that person is coming from. I do think it is true that if Biden does pass a measure of debt forgiveness when he takes office in January, whether that's $10,000, whether it's $50,000, in a real way, he will be expanding our political imagination and encouraging perhaps a broader reconsideration of the way we think about debt and the people who carry it and why they incur it.

Now that could perhaps lead to higher education reforms later on down the road that would lead to higher taxes. What I think you have to ask yourself, what we should all be asking ourselves, is that maybe it would be worth it to pay some higher taxes in order to get a higher education system that actually works for people and doesn't lead to situations like $1.7 trillion in student loan debt.

Brian: I think it's accurate to say the Tea Party movement came about a decade ago, partly in response to student loan debt mitigation proposals in Texas and elsewhere at the depths of the financial crisis. Would you expect something like that again?

Sarah: I think the situation is different for a number of reasons. One is that Obama is not the president. I don't think that you can disentangle the Tea Party's fixation on debt relief and mitigation from a racist backlash to a Black president, who was perceived as being radical and maybe working principally for people who were not the Tea Party base.

Second, the student debt crisis has become worse, not better over time, the pain is even more severe, and it's more widespread. Also, right now we're in the middle of a major economic crisis, again, that is accompanied this time by an ongoing pandemic. I think that the personal responsibility argument falls a little flat in 2020, perhaps in a way that it didn't in 2008, through 2010, which is when the Tea Party really got started.

Brian: We're talking, if you're just joining us, listeners, about one of the issues that will face President Joe Biden after January 20th. That will be the crushing amount of student debt in this country. At a time of pandemic economic crisis to boot the CARES Act, does spend all student loan interest payments, but that expires on January 1st. Biden's proposal during his campaign, and he reiterated it the other day, is to forgive $10,000 of student loan debt for many individuals. Some people want him to go further.

There's already backlash to even that, and we're talking about it with Sarah Jones from New York Magazine who has an article called "Student loan debt is immoral." Jonathan in Essex County, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jonathan.

Jonathan: Hey there, thank you for taking my call. Yes, I'm one of the millions that's been affected by these predatory student lenders and student loans. I went to culinary school and I graduated in 2007. I graduated with $42,000 worth of student debt, and I've done the math, and I've paid about $40,000 of that since 2007. I still currently owe $41,000. My recent monthly payments are $600 a month. I've been doing $600 a month for the past two years, even within the pandemic, which puts me up a little over $14,000 worth of payments for the past two years, and I still haven't even scratched the surface.

What I was telling your call screeners, at this point, I've been paying it for so long. Obviously, I want something to happen, but what's killed me the most is the interest rates. When you buy a car, when you buy a house, you know that after a certain amount of years you're going to be done with this, I don't know when I'm going to be done paying.

Brian: Sarah, talk to Jonathan.

Sarah: I think this is a huge, huge problem. The interest rates are really extreme. I don't understand why we aren't capping them. I wouldn't call myself an expert on the wide variety of regulatory reform [unintelligible 00:21:06] perhaps resolve the interest rate problem in particular, but the fact is that people will focus on the fact that student borrows did voluntarily take on this debt, but the interest rate is so high that even when you're making a good faith effort to work and try to pay down your debt, you really can't do that.

I just think that there's no way to argue sensibly that that's fair, or realistic, or that we should keep expecting people to do that. Addressing the interest rate piece of this problem is going to be huge. I do hope it's a priority for the Biden administration.

Brian: Jonathan, good luck. Someone tweeted, "Where does debt forgiveness money come from?" Is there a simple answer to that? Does it come from the tax coffers? Because it's owed to the federal government? Does it come from the banks? Is there a simple answer to that question?

Sarah: I don't think that there's a simple answer to it, but what I would say is that I do believe the federal government has the money. It's just a question of priorities. What are we spending money on? I have a hard time believing that we can't shift funding, take some away maybe from the Pentagon and put it towards making life better for people living right here in the US.

That's a conversation that's really overdue. I think we should have started it a long time ago, but maybe, if anything good comes out of this pandemic, if anything good comes out of this recession, it'll be having these conversations. I'm thinking a little bit more creatively about what we can do here to make people's lives better.

Brian: I think Susan in Ridgewood wants to bring up the banks. Susan, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Susan: Hi, I have a couple of points. First and foremost, when you graduate, you're no longer earning what you were maybe earning before. The rate of pay is lower. Second, you're immediately during college targeted by credit card companies, so you are also getting credit, and those things are adding up. Then thirdly, this is deeply impactful to your credit rating, so you get out of college, your credit debt to income ratio is so low that you don't qualify for any kind of assistance, and everything you pay more for, including car insurance in case you have a car.

Fourthly, the reason why the government, I think, should step in, and I wanted to ask you about this, is it because they've gone out of their way to deregulate and subsidize this industry? In fact, some of our politicians, including Betsy DeVos have ownership stake in some of these companies. You're more likely to be able to renegotiate your loan or debt to the IRS before you can get a renegotiate this loan. We bailed out the savings and loan industry, and did we go around asking people, "Why did you buy that house?" I just wanted to hear what your thoughts were. Thank you.

Brian: Thank you, Sarah.

Sarah: Susan, I think you're right on the money. I think that's a huge problem. We tell people in this country to pull yourself up by your bootstraps, go to college, get a good job, but it's true we aren't making as much as we were after completing college, maybe even a decade ago. Now we have these gigantic student loans with extremely high interest rates, and credit card debt on top of that.

In fact, most debt held by millennials is credit card debt. It's not actually student loan debt, student loan debt generally is the second most common form of debt. My interpretation of that data is that you graduate from college, you have this extremely high debt burden to begin with, whatever income you're bringing in as a result of the qualification you've earned, isn't enough to offset all of your expenses. Now you're taking on credit card debt on top of it. There certainly been the case for me personally in my household. I think it's actually quite a common problem.

Brian: Daniel at West Point has a suggestion. Daniel, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Daniel: Hi. I'm a first-time caller, but I listen to your show almost every day. Thank you so much for what you guys do. You bring great, great conversations to the New York area, but my comment and question for your caller is, my dad sat me down when I was 17 and said, "Hey, there's several pathways to college. One of them is taking up a tremendous amount of debt, and one of them is going to the military."

I did the National Guard and ended up going active duty. I find myself so far ahead of my peers when it comes to the student loan situation. Why don't we think about expanding public service or national service as a means of compensating or justifying debt forgiveness? One of the things, I think, I get a lot of traction with, with all kinds of people on this topic is this avenue of maybe allowing the Peace Corps or AmeriCorps, or some type of work program to allow people to work and connect themselves deeper to the nation while at the same time getting the same kinds of GI benefits that military members may get. I would just like to hear what your caller has to say about that.

Brian: Sarah, talk to Daniel at West Point.

Sarah: That's an interesting point. My partner is a former marine first-generation college graduate, and he still ended up with student loan debt despite the GI bill. The GI bill certainly is a major reform, but it doesn't cover everything. I don't have a problem with the idea of expanding public service in general, in this country, especially in the middle of an economic crisis. I think that could be really interesting and creative way of keeping people employed and paid. I'm not sure that I think that it should be tied to access to college and college affordability though.

I personally believe that education is a right and it should be accessible to everyone whether or not they're able to go into AmeriCorps, or the Peace Corps, or the military. I think you expanding public service, doesn't get it. Some of the deeper issues that are causing the student debt crisis. It doesn't really address predatory interest rates. It doesn't address rising tuition costs and rising costs of board on top of it. I think that it would end up being a bit of a superficial solution to what's actually a fairly significant and complex problem.

Brian: Daniel, thank you so much for raising that, and thank you for a first-time call, please call us again. We really appreciate it. We're over time, but I want to sneak in one more because James in the Bronx, I think, is going to bring up a proposal that was central earlier this presidential campaign season, but it hasn't come up yet in this conversation. James, you're on WNYC with Sarah Jones from New York Magazine. Hi there.

James: Hi, Brian, thank you for taking my call. Brian, I was actually telling that I took a loan when I was younger. Now I'm retiring, and I cannot afford to pay my loan now, and I couldn't afford to pay then.

Brian: You mean you're retiring and you haven't paid off your student loan yet?

James: No, but the point is, I can't even afford to pay now. I have $50,000 to pay. At my age, I can't even think how I'm going to pay it. Now to make a long story short. We have been given amnesty to everyone. This life is going on weeding to find a solution to our financial crisis. Money is designed by human to serve human. We've been all over the place when it comes to numbers, we have to think outside the box, otherwise our leaders will be repeating the same thing for thousands of years to come.

We can reset these-- Student loan, human need to be given a room for them to reassess, and to the new generation of humans to believe that it's worth going to school. In Europe, they're able to do it. Bernie Sanders and the other people are trying to let people know we can do better by just putting the human first, and then money second.

Brian: James, I'm going to leave it there because the clock is our enemy right now, but I think yours is the first-time call too. Please call us again. He said a name in there that we hadn't said earlier in the segment, and that is Bernie Sanders. Let's end on that, Sarah. Bernie Sanders ran on free public college. Certainly Joe Biden hasn't adopted that, at least not like that. How much do you think that's the solution? We have 30 seconds left.

Sarah: I think it will help. I do think it's true to this underlying principle that we've been talking about, which is that if education is a right and needs to be more affordable for people, but most student loan debt is actually for graduate school, for for-profit or colleges and universities and to private non-profit colleges and universities, plus professional schools like law and medicine. It would help, but there is more that we would have to do in order to really tackle the crisis.

Brian: Sarah Jones's latest article for the Intelligencer, part of New York Magazine, is "Student loan debt is immoral." Thank you so much for joining us.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.