Dr. King's Legacy and How to Challenge Persistent Segregation

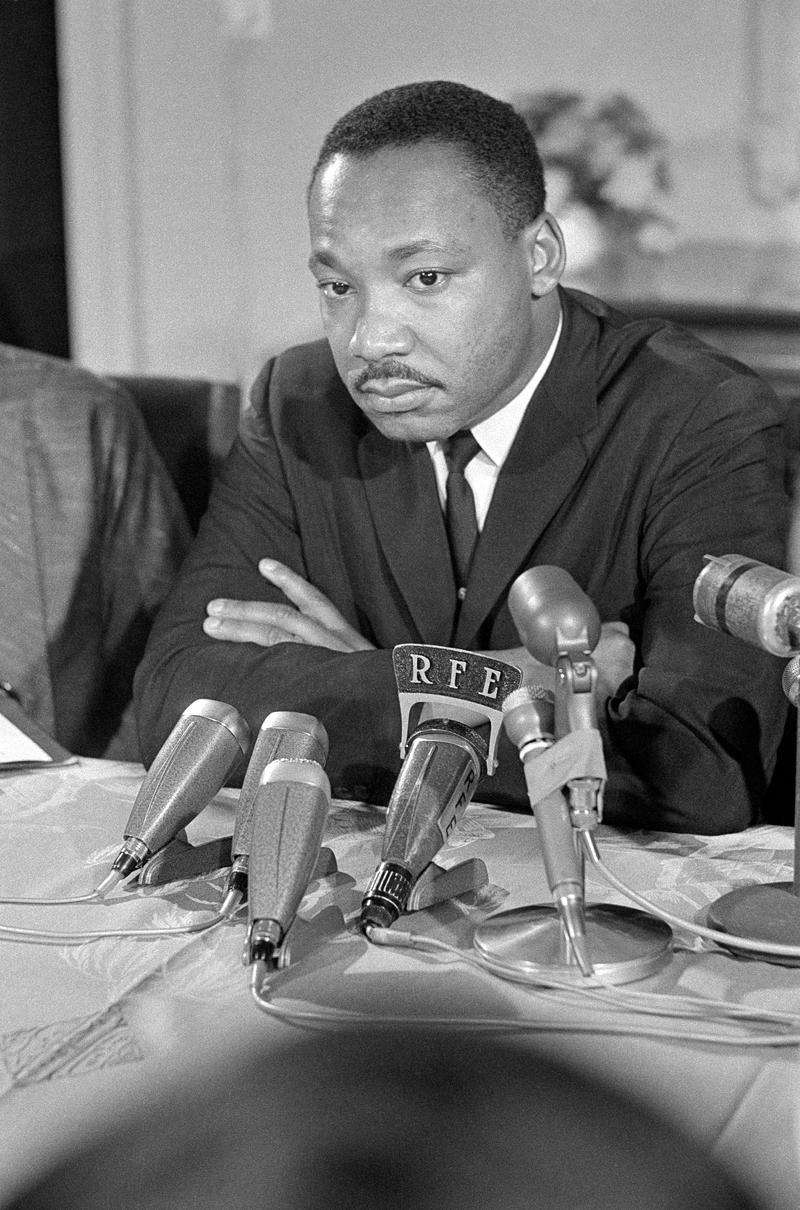

( Kurt Zarski / AP Photo )

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. We just heard Michael Hill, at the end of the newscast there, play an excerpt from our Martin Luther King weekend event at the Apollo Theater yesterday. Now, we're going to play another one because I did an interview that was originally for that event. We're going to air it here. The guests, as you will hear, are Richard and Leah Rothstein, experts and activist in the area of housing segregation.

Talking to the Rothstein's was very timely, given the barriers to affordable housing that we've been talking about a lot on the show recently with respect to our local area. Here's my interview for the Martin Luther King weekend event at the Apollo Theater with Richard and Leah Rothstein.

Hello, Apollo. I am here with Richard and Leah Rothstein, father and daughter. Their passion and expertise is fighting housing segregation. Richard is a distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute think tank and a senior fellow emeritus at the Thurgood Marshall Institute of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and well known for his 2017 book about the history of official housing segregation and discrimination, called The Color of Law.

Leah has led the Alameda County California and San Francisco probation department's research project on reforming community corrections policy to be focused on rehabilitation, not punishment. She has also been a consultant to nonprofit housing developers, cities, and counties, and others on affordable housing policy and finance. Together now, Richard and Leah Rothstein are co-authors of a book called Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law. Richard and Leah, thanks for doing this, and welcome virtually to the Apollo Theater.

Leah Rothstein: Thank you.

Richard Rothstein: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Leah, on the title of your father's book, I will give you the privilege of describing his book to everybody else, The Color of Law, would it be right to say that that title, that phrase, has a double meaning?

Leah Rothstein: Certainly. The book is-- it takes on this notion of de facto segregation, the idea that-- basically, that the law is colorblind, that we are segregated as a society by accident or by personal preference or private actions, that the government had nothing to do with it. The Color of Law took on that idea, basically debunked it, called it an utter myth by brutally laying out all of the government policies that went into intentionally creating a segregated society. The fact that the law is colorblind is also a myth. The Color of Law explains how local, state, federal policy took intentional actions, unconstitutional actions to ensure that whites and Blacks lived apart from each other.

Brian Lehrer: This wasn't just in the South. Richard, I saw a New York example that you wrote about in The New York Times just a few years ago that described how the New York State legislature amended its Insurance Code in 1938 to permit the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company to build large housing projects "for white people only." I think that was in the language somehow, you tell me, first Parkchester in the Bronx, which a lot of our listeners on the radio or audience members of the Apollo know. Applaud if you're from Parkchester. Then Stuyvesant Town in Lower Manhattan. Want to tell our audience a little bit about that story?

Richard Rothstein: Well, sure. The insurance company wanted to build those projects. The president of MetLife testified that he would not rent to African Americans in these projects, but in order to go ahead with the projects on that basis or on any basis, really, he needed authorization from the state legislature. He needed city involvement, as you know. In a project like that, you need to condemn land. There needs to be lots of involvement of the city to permit such a project to go forward and to allow it to assemble the land.

This was not a private development in any meaningful sense. Without government participation and endorsement of a segregated exclusive white community, neither of those projects could have gone forward.

That's a very small example of the kinds of policies that were followed all over the country to create segregation by government. Had the state legislature, had the City of New York followed their constitutional responsibilities, they would have had to insist that the MetLife rent apartments in those two projects on the non-discriminatory basis, but they failed in their constitutional responsibilities.

Brian Lehrer: Now, Richard, since this is our Martin Luther King weekend event, I wonder if you can talk a little bit about Dr. King's activism, specifically on the topic of housing segregation. I'm thinking, perhaps as an example that I think you were involved in, of his work in Chicago in 1966. I'll say by way of historical context, though a lot of our audience members know this, this is two years after the Civil Rights Act was passed, ending official Jim Crow segregation, at least on paper, in the South, but then he and his family, and maybe you, moved to Chicago to make a point.

Richard Rothstein: Well, I was already in Chicago at that time and was privileged to be part of that campaign. Reverend King understood that housing segregation underlay the most serious segregation in all other fields. Housing segregation is responsible for disparities of outcomes in schools for children because you concentrate the most disadvantaged, low-income African Americans in single schools. They're overwhelmed by their social and economic problems.

Housing segregation underlies health disparities between African Americans and whites because so many Black people live in less healthy neighborhoods, more pollution, less access to fresh food. In fact, housing segregation also underlies a good part of the explanation of the police abuse of young African American men that we spend so much time demonstrating against in 2020.

When you concentrate the most disadvantaged young men in single neighborhoods where they have no access to jobs, no access to transportation to get the good jobs, no access to schools that aren't overwhelmed by concentrated poverty, it's inevitable that the police are going to engage in confrontations with them to keep them under control.

Reverend King understood this. He determined to campaign, using Chicago as his primary example, for open housing, for non-discrimination in housing. He planned marches and undertook marches through white suburban and inner ring suburbs to demonstrate for open housing suburbs that excluded African Americans. They resulted in violence against him and against his marchers. That's the reason he came to Chicago.

Brian Lehrer: Leah, to continue with the history, then came the 1968 Fair Housing Act, one of the responses, I think we can accurately say, to the assassination of Dr. King and the outcries that followed. That, again, at least on paper, outlawed discrimination in the sale and rental of housing, but we know how much housing segregation there still is today. What would you say did and did not flow from the 1968 Fair Housing Act?

Leah Rothstein: Well, outlined discrimination in the sale and rental of housing is essential, but like you said, it's on paper. The enforcement of that law has to be taken into consideration, and it's not very well enforced. There's an example from 2019, not that long ago, in Long Island. The Long Island Newsday paper did an expose where they sent testers of potential homebuyers of different races with identical financial qualifications to realtors all over the Long Island area to see how they were treated, if they were treated differently by race.

In 50% of the cases, the African American testers were given fewer options of homes that were available, were steered towards same-race neighborhoods. This idea that the Fair Housing Act itself ended discrimination, is not true. We have to continue to enforce that that discrimination isn't happening both by realtors, by governments. It's constantly having to be litigated and enforced to ensure that discrimination doesn't continue. That's one piece of it.

The other piece is that the Fair Housing Act outlawed future discrimination, which is important, obviously, essential, but it didn't do anything to address the disparities that already exist as a result of decades and decades of government policy that created segregation. You can't just say that we will no longer discriminate in the future and expect segregated patterns to disappear.

One big result of segregated communities is a wealth gap that we see between Black and white households. African American households have about 5% of the wealth of average white households, 5% of the wealth. That's a huge disparity. When you say everyone has equal access to buy this home, but white families have access to so much more intergenerational wealth to be able to afford it, and African Americans don't because of past government policy that kept them out of home ownership when it was affordable and would've allowed them to build up wealth that way.

The Fair Housing Act is an important piece, but we have to also address all of the consequences that we're living with today if we want to truly desegregate and provide equal access to housing.

Brian Lehrer: Leah, your new book together is called Just Action: How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law. I'll bite on the how-to. Where do you start?

Leah Rothstein: What we argue in Just Action is that we need to reactivate the civil rights movement to take on this issue of residential segregation. The civil rights movement did a lot to desegregate public spaces, but it fell short of desegregating our communities. In order to do that, we need to start by building biracial multi-ethnic committees, groups in our own communities, that are ready to take on these issues.

Now, we understand that federal policy played a large role in creating the segregation that we live with today, but once created, to a large extent, it's maintained and perpetuated by local policies. These biracial multi-ethnic groups, once they're formed, there's a lot they can do in their own communities, challenging local policies, adopting local programs, pressuring local institutions and corporations to live up to their obligations to remedy the segregation they helped to create.

The book Just Action that we wrote has dozens and dozens of examples of these local actions and policies that groups can take on. They fall into two main categories—those that are concerned with increasing investments in lower-income, segregated, African-American communities, and those that are concerned with opening up exclusive, expensive, predominantly white communities to more diverse residents. All of these strategies are essential.

Brian Lehrer: Richard, I know you've written extensively on segregation in education as well, and here in New York, I'm not sure, under Mayor Adams-- You can comment on the current administration if you want, but under Mayor de Blasio, he used to say he wouldn't do much explicitly about segregated schools because segregated schools are basically a function of segregated housing, where kids live. He wanted to focus on that and hoped it would trickle down to school deseg-- I wonder how much you would agree or disagree with that as a tactic.

Richard Rothstein: I fully agree with that. That is the primary reason that we have segregated schools is because of segregated neighborhoods. It's actually a little bit less true in Manhattan and other densely populated areas of New York City, where you actually can draw school attendance boundaries in a way that would create more neighborhood schools that were not segregated, but much of the country, that's not possible, and almost all of the country, that's not possible.

You'd have to subject children to long bus rides away from home, take away the ability of parents to participate in their local schools, in the schools that their children attend. If you did that-- What we need are desegregation of neighborhoods so that schools can become diverse and not overwhelmed with concentrated poverty and concentrated disadvantage.

This is actually how I came to write the book The Color of Law. In 2007, the Supreme Court prohibited the school districts of Louisville and Seattle from embarking on a very token school desegregation plan because they recognized that school segregation was not advantageous to the achievement of Black children. The Supreme Court prohibited it from doing it, and Chief Justice John Roberts wrote his opinion prohibiting this very token plan.

It was a school choice plan. It wasn't mandatory. He wrote an opinion saying that the schools in Louisville and Seattle were segregated because the neighborhoods were segregated by private activity only. Government had no role in doing it. I realized, from my reading in the past, that these were segregated by government. The example I gave in The Color of Law about Louisville is a white homeowner in a suburb of Louisville who sold a home to an African American in his community, and the state of Kentucky arrested, tried, convicted, and jailed, with a 15-year jail sentence, the white homeowner for sedition, for having sold a home to a Black family in a white neighborhood.

This was well known. This is no secret from Chief Justice John Roberts. The notion that government had nothing to do with the segregation of Louisville or Seattle is mendacious.

Brian Lehrer: Leah, last question, I want to end by tying your book to the news of just this past week here in New York and New Jersey, where Governors Kathy Hochul & Phil Murphy made affordable housing centerpieces of their State of the State addresses, and yet we see fierce resistance to affordable housing construction, especially in the mostly white suburbs just outside the city.

That particular resistance sank Hochul's housing bills from last year, I guess because they believe lower-income people, disproportionately Black and Latino people compared to who lives there now will bring crime and other social problems. Or maybe they just don't want to live around people who are different from them. We don't know yet if anything will get past this year, but again, going back to the subtitle of your book, How to Challenge Segregation Enacted Under the Color of Law, and what you've both said here about building biracial multiethnic coalitions, do you have any advice for the New York State legislature for this year on how to get closer to yes on a badly needed housing construction bill?

Leah Rothstein: I think it starts by building support in our communities. Now, 20 million Americans turned out for Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, following George Floyd's murder. 20 million Americans is a lot of people. They were Black and white, young and old. They were from suburbs as well as cities, and if we think that we can-- If we can activate and reach those 20 million Americans, they went out to protest to march for Black Lives, and then they went home to put maybe lawn signs on their front lawns or maybe starting a book club to read about these issues, but then they didn't do much more.

We believe that they didn't do much more to really make Black lives matter, because it's hard to know what to do. One thing that they can do is support these kinds of measures to increase housing opportunities in these suburbs. We're facing a housing crisis, in part, because of the efforts that tried to keep these inner ring and outer ring suburbs white. They ensured that new housing couldn't be built in these communities to ensure that they stayed white, and we perpetuated and maintained a segregated society.

Once we understand that history, we can activate all of the people who marched for Black Lives in 2020 and come out to support affordable housing measures, measures that increase housing supply, that reduce zoning restrictions against building a variety of housing in every community, and that's what we need to really meet the demand for housing right now and meet our obligation that we have to remedy the unconstitutional actions that created these segregated communities. They're connected. We can't forget that.

Brian Lehrer: There's an old saying, I think it's actually an African proverb, that goes "Not to know is bad, not to want to know is worse." I wonder if there's something, Leah, in that concept that can be used to help build the allyship that you've been talking about.

Leah Rothstein: Yes. We live in a very segregated country. I don't think anyone here, any of us can deny that. We all live in areas that are segregated by race, particularly whites and African Americans living far apart from each other. If we look at that and think that that's just natural, that's just how it's supposed to be, that's just something we have no control over, then we have no obligation to do anything about it.

We have no desire to learn how it came to be that way, and we also don't have to confront all of the consequences of that segregation. The segregation of our country underlies our most serious social problems. Health disparities, economic disparities, educational disparities. Those who grow up in segregated African-American communities have shorter life expectancies than those who grow up in white communities.

We're talking about quality of life, length of life. This isn't something we can ignore. Willfully ignoring why we're segregated, what the consequences are, just ensures that we continue to perpetuate these issues and these problems, and they affect all of us. It's unwise to think that some of us can get out of the effects of segregation. Once we confront that and start to learn about how it came to be, we start to see in reading, for example, The Color of Law, that the government had a huge role to play in this, took actions that were contrary to the constitution, and when our government does that, we have an obligation to do something about it.

I think The Color of Law was very popular around the country. I think partly because we didn't know about this history. Collectively, we had forgotten the way that the government created segregated communities and once we remember and reckon with that history, it gives us an obligation to act. I think it's worse not to want to know because then we continue to perpetuate these problems and these issues and think that we have no role to play in fixing them.

Brian Lehrer: One other thing on allyship, do you ever see your role in this movement as white people, if you consider yourself white people, in part being to leverage the interest and allyship of other white people because it might be easier to relate to you? Richard?

Leah Rothstein: Definitely.

Brian Lehrer: Leah, go ahead.

Leah Rothstein: Yes, that was it. Go ahead.

Brian Lehrer: Richard?

Richard Rothstein: Well, let me add that there's an enormous desire to know in this country. I don't mean to boast but The Color of Law sold over a million copies. It was on the bestseller list for over a year. The readership was primarily just because of numbers, whites, although large numbers of African Americans read it as well, and they passed it around to friends and colleagues and neighbors and held book groups about it. People were stunned to learn this history, and they were desperate to learn more.

The reason we wrote Just Action was because so many people who read this book, said, "We didn't know this before. Why weren't we taught this in school? Why didn't we learn this in our classes? What can we do about it now?" That led to the book Just Action. I think there's an enormous appetite in this country to learn things that have been hidden from them and forgotten. That's expressed by the readership of The Color of Law and by the interest in this new book, Just Action, which tells people how they can actually do something to remedy it.

Brian Lehrer: Richard and Leah Rothstein, thank you so much for joining us today.

Leah Rothstein: Thank you so much.

Richard Rothstein: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: That interview was originally for WNYC's Martin Luther King weekend event yesterday at the Apollo Theater. Program note, we will also air a one-hour edit of other portions of the Apollo event at two o'clock this afternoon as a special edition of our program Notes From America with Kai Wright. Kai and guests from the Apollo event called The Inconvenient King coming up at two o'clock this afternoon here on WNYC.