Dispatch from COP26: Nationalism's Influence on Climate Policy

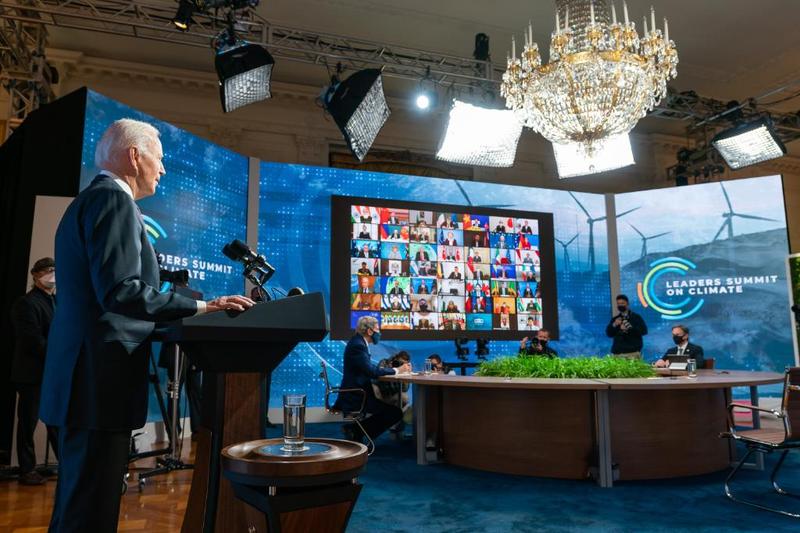

( The White House )

[music]

Brian: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again everyone. Now we continue our coverage of COP26 the United Nations Climate Change Conference going on in Glasgow Scotland that began this week. We're going to go live to Glasgow in just a second for journalist Kate Aronoff who's got some very interesting ideas, not only coverage. This is the second day of the conference's world leader summit where President Biden spoke yesterday touting US climate policy.

We'll get President Biden up here in just a second. I will say about Kate Aronoff that in addition to being at Glasgow and covering the day-to-day, she's also interested in the intersection between nationalism and climate protection. Of course, we're in a very nationalist era right now Trump in the US was not the only example and also democracy and climate protection. She wrote an article in Dissent Magazine in 2019 called the European Far Right Environmental Turn, positing that as climate change becomes a central concern for voters across the continent, right-wing parties are beginning to incorporate green politics into their Ethno-nationalist vision. That sounds dangerous.

She wrote a similar one in The Guardian this summer called Is Democracy Getting In The Way of Saving The Planet. There are a couple of scary thoughts right there that will go over with Kate Aronoff live from Glasgow. Here's 10 seconds of President Biden yesterday at COP26.

President Biden: My Build Back Better framework will make historic investments in clean energy. The most significant investment to deal with the climate crisis that any advanced nation has made ever.

Brian: Will it actually pass? Sometime later yesterday and some 3500 miles away, Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia also spoke about the Build Back Better plan in DC. He doesn't say, "I'm protecting the coal industry," in this clip, but listen between the lines.

Senator Joe: I will not support the reconciliation legislation without knowing how the bill will impact our debt and our economy and our country. We won't know that until we work through the tax. I'm open to supporting a final bill that helps move our country forward but I am equally open to voting against a bill that hurts our country.

Brian: In that speech, Manchin urges the house to instead pass the bipartisan infrastructure bill which leaves out many key climate provisions. Joining me now from Glasgow is Kate Aronoff, staff writer at The New Republic and reporting fellow at the Climate Social Science Network. She's the author of the book Overheated: How Capitalism Broke the Planet--and How We Fight Back. Also co-author of A Planet to Win: Why We Need A Green New Deal. It's clear where she's coming from. Kate thanks for coming on from Glasgow. Welcome back to WNYC. Hello from New York.

Kate: Hello. Thanks so much for having me.

Brian: What's your headline from over there so far?

Kate: I don't know if I have a headline yet. Thankfully I don't have to write those which is a nice part of my job, but it's a fairly chaotic scene in a sort of immediate physical sense. There are hours-long lines to get in the door because the UN and the UK government have put in place, rightfully so of course, COVID protocols, and there are just a tremendous amount of people who are around. It's been more, I would say, having gone to a few of these a slightly more chaotic start to these climate talks than usual.

Yesterday kicked off this World Leaders Summit that the UK government is convening which is layered on to this first week of talks. Those are technical negotiations that usually don't have as much press coverage or usually aren't as high profile. All of those things converged in Glasgow. It's a very, very busy place right now.

Brian: Are they going to do anything that matters to the climate in your opinion?

Kate: We've seen a lot of pledges, which is the norm for these sorts of events. There is a methane pledge where 80 countries led by the US and the EU are pledging to reduce methane emissions by 30% below 2020 levels by 2030. India came out with a somewhat surprising net-zero pledge to go net-zero by 2070. There was an agreement to end deforestation by 2030 by several governments. There's a lot of talk, but unfortunately, the UN is a bit limited in the tools that it has available because it doesn't really have a say over things like trade over these other institutions which really can move capital around, can do things like fossil fuels in the ground.

The limitations of this format are pretty clear and it's really is up to governments themselves and to other international institutions is have more teeth to really make sure that some of the pledges that have been made here, which are positive, can become reality.

Brian: This is the way that these environmental treaties tend to work is my understanding and this is where your interest in nationalism also starts to come into play, I think. The treaties start to work, and correct me if you think I'm wrongly or overstating this, the Paris Climate Accords too that the different countries make pledges about how much greenhouse gas reduction they're going to do by when. There's nothing to really enforce that but the nature of these conferences and these many nation signatory treaties is that they come together, say at conferences like COP26, and they nudge each other in the direction of actually doing what they've promised to do.

Then nationalism, or at least each country's individual interest that might go against the interest of the greater world, comes into play to oppose it. Each country wants to maximize its immediate economic output, for example, and that might work against climate provisions actually being enacted. Do you want to pick it up from there and talk about the intersection between this global mutual nudging that takes place and what you write about with respect to nationalism?

Kate: Mutual nudging is a really great way to put that. I think it's worth a bit of context here. Without going into the very very deep history of the UNFCCC United Nations Framework on Climate Change which was created in 1992 or the history of the UN itself which is very complicated. It's just worth noting where the Paris Agreement, which is where the system of nationally determined contributions comes from of every nation making its own pledge, as you mentioned, to bring down emission.

There is a previous global agreement called the Kyoto Protocols that the United States pulled out of in 1997 under the direction of one West Virginia Senator and another Senator Chuck Hagel. That really sent the world back to the drawing board in terms of how we come together to take on this challenge. One of the United States is real demand in that process and made clear that it would not agree to anything with finding commitments that would require a Senate to pass.

A lot of this process has revolved not only around the United States and its demands, around many wealthy nations of course, but that really shapes the Paris Agreement and what it can and cannot do. As we mentioned, we are in this place of individual contributions, the so-called bottom-up system, as opposed to what was in place with Kyoto which established a firm definition of what's so-called Annex 1 countries, largely wealthier nation who had more capacity to make binding emissions cuts.

That would have required not only that countries who are responsible for the lion's share of emissions historically, not only that they bring down their emissions very quickly and create a framework for that to be binding, but also establish financial responsibility which is one of the big issues in these talks. The Paris Agreement also does not outline a means through which wealthier countries can make it possible for countries who have not benefited from decades and in some cases centuries of development for developing countries to transition as well and to adapt to climate change.

That's the microhistory of why we have the bottom-up nationally based system. That has really led us to a place of having to rely, as you said, on this mutual nudging which someone likened recently to a group of people being in a room trying to decide what movie to watch and the goal-- You can't watch a movie until everyone decide what it is. The goal really isn't to watch a movie, the goal is to keep a big from breaking out that disbands the entire process.

That is really what we're doing here and it is very, very difficult to come to an agreement. Certain players really have an outsized role on that. The United States of course can throw a lot of weight around and house historically in pretty similar ways regardless of if it's a democratic administration or republic administration. Really fighting off firm financing commitments and conversations about historical responsibility. That is not, I would say, a collective action problem so much.

I think there's this received wisdom that governments just can't do this, that we can't come together and figure out a solution to this problem. There are power balances at play. Certain countries drill a lot of fossil fuels, certain countries really do have a lot bound up in this and have an outsized role. Many developing nations are on the losing end of the climate crisis, bear very little responsibility. If the UN were a democratic system if it were one nation, one vote, then we probably would have solved this a while ago. That unfortunately is not how this thing functions and a handful of wealthy countries can really really put their hands on the gears.

Brian: Right. You get into these disputes over things like, and I think this is one of the excuses that Trump used for pulling out of the Paris Climate Accords, the wealthier industrially developed nations like the United States which produced most of the climate crisis because we've been responsible in the US and Europe and maybe Japan, a few other places, these days China, for emitting most of the greenhouse gas emissions while the less industrially developed countries did not.

Those countries are also much poorer and have an interest in developing their economy so the Paris Climate Accord gives the US less right to keep polluting the environment than some poor developing countries. Trump or someone else can come along and say, "Wait, this isn't fair to us. We are not allowed to burn coal so much anymore but we're telling the poor countries, "Yes go ahead and burn coal for a while so you can get wealthier." Even though their coal pollutes the planet just like our coal pollutes the planet." You have to hold two thoughts in your head at the same time kinds of provisions that become political playgrounds for people who want to obscure the bigger picture.

Kate: That is in practice how it works out a lot. I mostly cover the United States and that's part of why it's so frustrating to watch how the Biden administration has positioned itself vis-à-vis these talks. In the months leading up to this, John Kerry has gone around to other countries lecturing other countries about not restricting fossil fuels oil, gas, coal. In the meantime, the United States is the world's third-largest exporter of natural gas. We are a major oil exporter, have not agreed to a coal phase-out, and so it's frustrating and it's frustrating for many delegates from the Global South and Civil Society Organizations to see the US come in swaggering claiming these big commitments and calling itself a climate leader when we have very little to show for ourselves.

We still don't have a climate law on the books, continue to drill oil and gas with abandon, and have not come to match the rhetoric that the administration is putting out. That's of course not only a US problem again, but there is really a gap between what the Biden Administration is saying and what it's doing.

Brian: It does bring us, though, to the unique case of China, where China is currently, I think, the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world. It's also considered a developing economy, so under Paris, it's allowed to pollute more than the US is allowed to pollute even though it's the number one emitter. Certainly, Trump hung pulling out of the Paris Accords largely on that before Biden got back in. How do you resolve the question of China in your head?

Kate: I will just say briefly that there's not, within the Paris Agreement, necessarily a structure by which countries are allowed to pollute more and less. There's no one saying if you do that then you'll get in trouble. It is really a sort of honor system in that regard. On China, this is the major thing that has changed from the days of the Kyoto Protocol until when the Paris Agreement was being negotiated. I will not claim to be an expert on China. Thinking about its commitments on climate requires holding a couple of things in your head at once.

As we mentioned it is now the largest emitter of greenhouse gases in the planet, the United States the second has also been a really massive developer of green energy. Has rolled out things like electric buses, train lines, all this green technology at a really rapid pace since the recession and has per capita greenhouse gas emissions that are about hal, still of the United States and have grown 75%. I think it wouldn't make sense to take the position that was more popular 20 years ago or so and say China's just like every developing nation and should be held to the same standards. China's of course a major emitter but I think it requires thinking with a bit of nuance which is not always the easiest in US media or politics.

Brian: Listeners we can take some phone calls for Kate Aronoff from The New Republic who is in Glasgow Scotland covering COP26. Who has a question for her? A chance to talk to a journalist actually covering COP26 who is there right now. 212-433-WNYC. 212-433-9692 or Tweet a question @BrianLehrer. Some calls might come in here Kate. Let me get more into the nationalism and right-wing authoritarianism connection to COP26 potentially and climate protection in general. I read at the beginning of the segment before you came on, little headlines or lead lines from two articles that you've written in different magazines at different times which raise potentially really challenging questions for democracy.

As you know you wrote in Dissent Magazine in 2019 an article that began as climate change becomes a central concern for voters across the European continent right-wing parties are beginning to incorporate green politics into their Ethno-nationalist vision. Oh-oh, are they hooking their really dangerous stars to green policies and making themselves more popular that way. Then in one in The Guardian this Summer your headline was Is Democracy Getting In The Way of Saving The Planet? First, how do you answer that question? Do you see democracy as somehow hampering climate protection and authoritarians as somehow claiming that they're going to be better at it?

Kate: The spoiler answer to that article is no. I don't think democracy is what's hampering climate progress but really a lack of democracy. Look in our own backyard, one senator elected by less than 300,000 people is holding back the agenda of a president elected by 80 million people. That is not what I would call the tenants a very functional democracy. I don't think is an indictment of democratic institutions writ large. If we had a more democratic government there was a good chance the United States would have passed climate policy.

I think the same holds true for the UN. As I was saying, there was a moment in the United Nations history where there was an attempt to make it a thoroughly democratic process, to have one nation, one vote really coming off of this wave of national liberation struggles, decolonization struggles that was struck down. We find ourselves where we are now. I think the question is really can democracy expand on the same timeline that we need to save the planet on the timeline that we need to reduce emissions in such a dramatic way to keep them below 1.5 degrees Celsius.

I think that's the real challenge and there's this tendency, as you were mentioning for people, to look at some of the failure of these institutions of the US government, of the UN system and say, "Well maybe it would be better if we just had some benevolent authoritarian who wanted to bring down emissions at a rapid pace." Whether- on the national level or some climate Leviathan as Geoff Mann and Joel Wainwright have written but what you see from Trump to Jair Bolsonaro is that the politicians who expels this authoritarianism are not the politicians who want to limit emissions. The 2019 piece is really looking at this phenomenon of right-wing parties realizing that they need to say something about climate change in order to win over voters who are very concerned about that especially in the European context.

That shouldn't be confused with this idea that that authoritarians are some answer to the climate problem. A lot of those riping plans are really disingenuous are not thinking seriously. Do not have some alternative vision of getting to 2 degrees Celsius but really are opportunistically looking at the climate as a way to put forward their really xenophobic and racist agendas of restricting migration, of criminalizing Black and brown people. I think the problem, just to sum up, is really not enough democracy rather than too much.

Brian: When I was in China a few years ago one of the biggest arguments that I heard as just a Xi Jinping's was coming to power from those I met there who supported the Chinese system, was that your democracy in the west is just too messy. Look how China authoritarian, yes, but in the name of the people, makes progress when the US gets stuck in political gridlock with your ineffective democracy. Of course, that completely whitewashes a lot of the horrible things that the Chinese government does to its own people.

The pro authoritarians make that case and it's something that president Biden has talked about a lot too since being inaugurated. He sees one of his missions as reconvincing the world that democracy can actually make progress on things and try to fight the rise in authoritarian states around the world in that way. That's an even bigger conversation maybe than we're having hear about the climate. Let's go to a call. Fritz in Queens you're on WNYC with Kate Aronoff covering the COP26 Climate Conference in Glasgow, Scotland. Hi Fritz.

Fritz: Hi Brian. Hi your guest. I want to put some nuances to what she said regarding China. I have three points. Point number one, you have to keep in mind, remember that the population of China is over 1 billion people. When you're talking about polluting to keep that in mind. Point number two, 20 years ago China was one of the poorest countries in the world therefore China could not be polluting then. Number three, advanced countries have undergone the Industrial Revolution for, I don't know what, many, many years so they've been polluting since then. Please keep that in mind those nuances. Thank you very much.

Brian: Fritz therefore what? Therefore you're reinforcing the idea that developing countries should be given more rights to pollute for a while.

Fritz: They should go easy on them, yes. In a way, go easy on them.

Brian: Fritz thank you very much as anti-poverty measures. That's part of the problem of holding two thoughts in your head at the same time for big policy conversations that we were talking about before, Kate? Because on the one hand, it has to be a priority to fight climate change. On the other hand, it has to be a priority to fight global poverty and inequality. Sometimes even though we would like to say that those two things don't have to be in conflict sometimes they're in conflict.

Kate: Absolutely. It is a really tough problem to think about and the question that comes up a lot here and in climate policy conversations more generally is whether the path toward development is a linear one that involves fossil fuels. Whether it necessarily means a lot of coal, oil and gas. One of the longstanding demands from many countries in the Global South who are vulnerable to climate change is for the wealthier nations in the north who have the ability to transition very quickly is to make a low carbon development path available through real financing commitments. Through things like technology transfer not tying up vital green technologies with patents that give profits to a handful of corporations.

There is a path that doesn't involve just building a bunch of coal plants, which is unfortunately, a reality right now for a lot of countries, but that will not change if there is not a real commitment of resources from wealthier countries to make that possible. China's role I think is an interesting one in that regard because it is a very wealthy country now, a deeply unequal one in some ways but it's not in the position of many other countries within the G77 group of developing nations. I think that tension is good to keep in mind and not one that's going away.

Brian: You bring up another provision of the Paris Accords that we didn't touch on yet which is also kind of a third leg to this stool of the richer, more developed countries cutting back really fast, the poor developing countries being allowed to cut back more slowly so that they can develop their economies. The third leg is the richer countries like the United States are supposed to give a lot of money to some of the poorer countries so that they can develop their economies with greener technology and not just rely on what may seem to them the cheapest short term solution, things like coal. Derek in Brooklyn you're on WNYC. Hi Derek.

Derek: Hey. Good morning. How you doing? I love your show.

Brian: Thank you.

Derek: The reason I think why none of these agreements are going to work at all is because of Joe Biden's history. Instead of coming to the American people and saying we need to fix this problem and we know there are going to be major side effects or major long-term effects and to sell it and I'm going to make sure everyone's protected. If you're any middle-class type of person in 10 years from now if they sign this and everything goes haywire, all my expenses go up and I can't drive my car, everyone's just going to vote for someone who's said as I'm pulling out of the agreements and we are going to go back to the old way.

For example NAFTA, NAFTA was this great thing to sell, we're going to solve all the world's problems. He gutted out white America in the middle of the country Trump came along. The big '94 crime bill, Biden went screaming for it. It decimated an entire generation of Blacks. Mr. Joe Biden is the greatest wrecking ball of a politician that we've had in the century, well see what he's done to the American people. Nobody thinks that Joe Biden thinks strategically and that is the problem.

Brian: Derek, thank you for your call. Kate, he's coming from a particular political point of view, but do you have any reaction to that with respect to Biden who, whether you agree with his policies, agree with Trump's policies, agree with some of the things that Derek was pointing out there or arguing whether Biden is showing himself to be the guy to get this done.

Kate: I wouldn't go so far as to say that Joe Biden is the reason why the Paris Agreement might not work. I think that's a bit of a strong statement. What is true is that the United States has really not made it clear that a transition away from fossil fuels can be one that doesn't screw people over, that doesn't throw people whose livelihoods depend on this under the bus. I think without a real clear commitment that that's going to happen, expanding welfare states, making sure that people are looked after, can retire early from jobs in fossil fuel and producing fossil fuels or in the fossil fuel economy more broadly that that's not going to happen.

Joe Biden's own history aligns with some of the reasons why we can't have those sorts of big welfare state programs, has certainly supported waiving some of those programs. I don't think he's the problem necessarily so much as one symptom of some of the broader problems, endemic to climate policy.

Brian: There we leave it with Kate Aronoff. You can hear more from her at the New Republic and the Climate Social Science Network. She's in Glasgow covering the COP26 climate summit right now. You can also check out her books Overheated: How Capitalism Broke The Planet-- and How We Fight Back and A Planet To Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal. Thank you so much for coming on from Glasgow today we really appreciate it.

Kate: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.