Did Amazon Set Itself Up to Fail?

( Richard Drew / Associated Press )

Brigid Bergin: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Welcome back, everybody. I'm Brigid Bergin, filling in for Brian today. It's that time of year when many of us are doing more shopping than usual looking for gifts for the holidays. Although many of us love the idea of taking a day to shop our local businesses, sometimes life gets in the way. When we're looking for convenience, there's one retailer that many of us rely on, and that's Amazon.

According to a new piece in The Atlantic's material world column, many of the tactics that Amazon has employed to dominate the market may render its very existence obsolete. After all, it's no longer the cheapest place to buy goods. You know this if you're one of the 100 million Americans who are active users of Temu, the Chinese marketplace headquartered in Boston that offers $10 AirPods and $3 cooking spatulas. It's also never been the most direct way to get your things as we can all just head over to our local Target if we still need something in a flash.

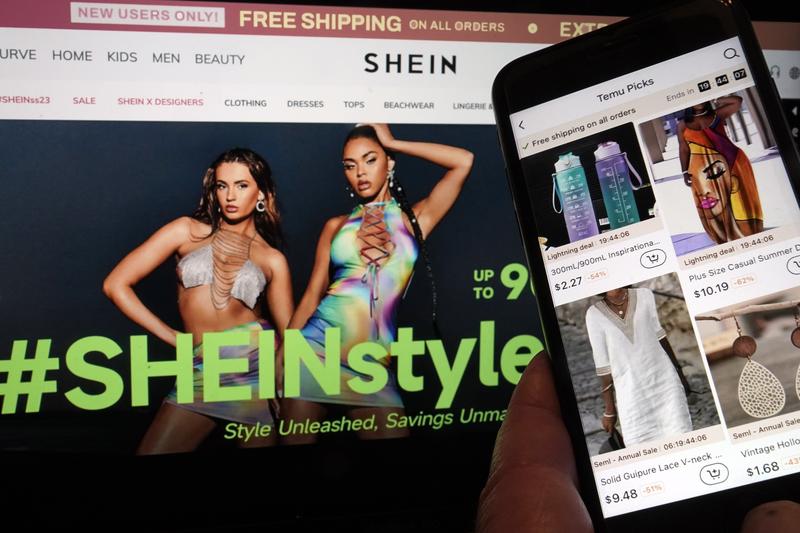

What is it that separates Amazon from rising competitors like Temu and Shein, as well as long-existing ones like Target and Walmart? Is there something that Amazon excels at in particular? Joining us now to answer these questions is Amanda Mull, staff writer at The Atlantic. Her most recent piece is called, Is This How Amazon Ends? Amanda, welcome to WNYC.

Amanda Mull: Thank you so much for having me.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, you start your piece off by describing Amazon's relationship with customers as the balance that resulted in its enormous profitability. What are we expecting when we order from Amazon, and why has it worked out so well?

Amanda Mull: I think fundamentally, what Amazon has trained customers to expect out of the Amazon experience is a product that often enough is good enough. Amazon has incredible scale, it has millions and millions of product listings, most of them listed by third-party sellers who don't go through Amazon directly to sell their products in a wholesale fashion as you would at other types of multi-brand retailers. You've got lots and lots of small businesses or medium-sized businesses all over the world writing their own listings, listing their own products, and that can make the process of shopping on Amazon a little bit confusing and a little bit uncertain at times.

Amazon is really known well for its logistics services and quick delivery, and it'll take things back. People have basically said, "All right, that's fine. I'll do the digging, and I know Amazon will get it to me quickly."

Brigid Bergin: You write about how through shopping on Amazon, American consumers have come to accept a "fundamental jankiness" both on the site and with the goods sold on it. What do you mean by fundamental jankiness, and why is it like this?

Amanda Mull: Well, the experience of using Amazon as an interface, whether it's through the website in your computer browser, or through the app on your phone, is just a little bit old school. It's not very slick. It's a little bit crowded. There's a lot of things going on simultaneously, and that is different than a lot of the apps and websites that we use in everyday life, and especially other types of retailers, which aim to make everything look clean and reliable and straightforward and high end often, even if the goods being sold aren't high end, because those are all marks of reliability and respectability and high quality.

Amazon has a little bit of a different issue at hand in that they have this enormous amount of scale and all of these different people who aren't direct employees making their listings. Everything is just chaos a little bit on Amazon's website, and the products too are a little bit chaotic. When you have millions of individual sellers deciding what they're going to put on your website, that means you're going to have lots of duplicate listings of the same thing, you're going to have lots of people selling things that might be the same thing, but you can't really tell from the photos, things that are from brands that nobody in the US has ever heard of, things that don't really have a brand at all, so it make it hard to evaluate the individual products.

Some of those products are great and as good as the things that you would buy at a store in the US. Some of them are not. Some of them are maybe dangerous or maybe counterfeit. Those are all problems that Amazon has worked to deal with over time, but at the scale Amazon operates, it's just not fully able to deal with all of them and shoppers have to navigate that on an individual basis.

Brigid Bergin: Part of what you warn about in this piece is that our acceptance of this fundamental jankiness may lead to Amazon's downfall and there are competitors like Temu who have come into the picture. What is Temu? How does it threaten Amazon's existence? There's another outlet, I think I mispronounced it, I guess it's Shein, which is in clothing, I think primarily brand. Can you talk about how they are playing in this space now?

Amanda Mull: First, don't worry about mispronouncing Shein because in my head, I still say it Shein, like it's a German word, but no, it is Shein, but I think everybody has a little bit of a problem with that. These companies are-- Shein is based in Singapore now, Temu is based in Boston, but they are both founded and owned in some respect, and it's a little bit hazy as to how, by Chinese companies. The source of a lot of the goods that we buy on Amazon, that we buy in Walmart or Target, or wherever, is China ultimately, they have enormous manufacturing capacity for consumer goods in particular, and they are the largest importer of consumer goods into the US.

What a lot of these sellers in China seem to have decided is that, well, it's expensive to sell on Amazon. Amazon takes enormous cuts of each sale from its marketplace sellers, these third parties. Shein and Temu take much smaller cuts of each sale and they carry a lot of the same stuff. Amazon disputes that, but if you look on a product-by-product basis, you can find a lot of similar things on Shein or Temu. I think a lot of shoppers that are especially price-conscious have started to say, "Well, if this stuff all looks the same, and I can't tell where any of it is coming from anyway, then why not just get the less expensive thing?"

Brigid Bergin: Listeners, this is your chance, have you ventured outside of Amazon and actually bought something from Temu? Did the incredibly low prices tempt you to try it out? What did you purchase? How much was it? Did the item come to you as you expected it? We're going to take your questions for our guest Amanda Mull, staff writer at The Atlantic. You can call us at 212-433-WNYC, that's 212-433-9692. Before I even asked, Gregory in Harlem, I know you have a story about something from Temu. Gregory, thanks for calling WNYC.

Gregory: Hi, thank you for taking my call. Thank you. Listen, Temu is-- I'm sorry, it's just wrong. I ordered shoes from them. The sizes was wrong. I sent them back. They do accept returns very quickly, and it did take like 14 days for them to get to me, so there's that, but they were the wrong size. The same with dress shirts. Well, they're no name dress shirts. I wear dress shirts, and I get them from Amazon, and they are who they say they are and the right size. Nothing seems to be the right size with these guys, except that one time that I didn't order thread. You can't mess up thread.

Brigid Bergin: Did it hold?

Gregory: It takes--

[laughter]

Brigid Bergin: Gregory, thank you so much for your call and being our first listener to tell us about their Temu purchase. We have a board of callers coming in. We're going to get to more of you shortly. Amanda, the point that Gregory raised, I think is really an important and interesting one, sizing. I think he said the sizing was not accurate. Is that something that you found as an issue specific to Temu, or is this specific to the fact that these products are not vetted necessarily in the same way you would if you were purchasing from another outlet?

Amanda Mull: I think that this issue of clothing sizing is a real issue with sellers that are trying to sell more directly from especially Asian garment-producing countries to the US because expectations of what sizes mean are just different. Those producers that have a lot of experience dealing with American companies and American brands will have a lot more experience in understanding what Americans expect of their sizing. Those that have less experience that supply mostly domestically in the past or that supply other countries, are going to have a harder time. This is something that on Amazon is very touch-and-go.

I've ordered clothing from Amazon that has been the correct size, as expected, and I've had the same experience as Gregory where I ordered something and it was like, "This has no relationship to the size that I ordered in what an American would expect." I think that clothing is an especially difficult problem to work out because there are so many sizing issues with it. I think that it is to be expected that Temu and Shein are not doing quite as good of a job figuring out sizing with their sellers as a company that has more experience selling to Americans.

Brigid Bergin: Jodi in Maplewood, you're on WNYC.

Jodi: Hi. Thank you for taking my call. I'm currently wearing Happy Fri-Yay earrings that I bought from Temu. Yes, I have bought from Temu here and there. I will say the quality is definitely not great, but the prices are really, really hard to beat. I am a teacher and I buy a lot of teacher stuff on Temu, things for my classroom and things like that. I really want to buy [unintelligible 00:10:59] and locally, but I think something that a lot of us struggle with is we don't make a ton of money, we don't have a huge cash flow, so when we see things that we might need or want for $10 less than we buy them otherwise, it can feel hard to pass that up. On the other hand, I really don't want to support unethical business practices and things like that. I think a lot of us feel torn. [laughs]

Brigid Bergin: Jodi, thank you so much. Your earrings sound great, by the way. Amanda, the point that Jodi raises leads me to my next question. When you see items for sale at, say, Walmart, there's a $10 spatula at Walmart, might be $8 at Amazon, but on Temu it's $4. Are we talking about the same products here? It's understandable why someone like Jodi might want to buy the one that's cheaper if it's the same thing in all these spots.

Amanda Mull: It's totally understandable to look at those prices and look at products across a variety of retailers and go, "I don't know what the difference is here." None of these are clearly better than any of the other ones, especially when you shop online. You're just looking at a picture, you're trying to predict what something will be when it's in your hand. I think that that is what drives a lot of people to give Temu and Shein and similar types of retailers a shot. Some of that stuff is going to be the same, is going to be indistinguishable when you actually get it in your hand. Other things are going to be much lower quality. It's hard to say when you're ordering and when you're looking at these stock images, exactly what is going to yield what kind of result.

That is something that is a fundamental issue with online shopping, with shopping on Amazon, with shopping anywhere, is that as a buyer, as an individual, you have so little information about what it is that you're actually going to end up with in your home. When you combine that overall lack of understanding with the information available to you and price pressures and monetary pressures that people feel because of inflation, because of their own budget issues, because of a variety of things, that is ultimately why a lot of people go, "I don't know the difference anyway until I get something in my hand. I can't tell why I should spend twice as much on this." People just give it a shot.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, how do companies like Temu and Shein manage to make money when their products cost next to nothing and how do their profits compare to Amazon or other retailers that maybe we're more familiar with like Target and Walmart?

Amanda Mull: Well, it's a little bit hard to tell on the fine grain financials of these companies because Shein I think either recently filed for an IPO or is about to, or has said they will. We'll have some more transparency from them soon, but otherwise, they're private companies and they disclose what they feel like disclosing. What the reporting has shown so far is that Temu, in a move that it is really normal for tech companies especially, is pricing things so low that they are not making a profit on many of the things that they sell. That they are choosing to lose money in order to acquire market share from their earlier competitors who already have more of established market. In that case, that is Amazon.

They're saying, "Right now the most important thing for us is to buy market share. We're investing in acquiring customers, and that won't last forever." You see that across tech. That's why Ubers and Lyfts cost more now. That's why things on Amazon cost more now, quite frankly, that's among the reasons, is because once you've acquired a significant market share, once you've established a consumer habit in people, the prices can tick back up and you can start to make more of a profit.

Shein I think has said that they are profitable and have been profitable recently. Part of what happens with that is that Shein and Temu have enormous investment, enormous scale, and are able to put a lot of pressure on producers of their products to absolutely cut as many costs as possible. They hold wages really, really low, the suppliers work people for really long hours. There have been accusations of forced labor in the supply chains for both of them. There are multiple fronts on which they push to lower these prices and sometimes that means they will be profitable, sometimes unprofitable, but there is always that backend of pushing material qualities low, pushing production times shorter, and pushing people to produce more products in their factories.

Brigid Bergin: Well, on that labor point, I want to go to Brian in Harlem. Brian, you're on WNYC.

Brian: Hi. How are you doing? Can you hear me?

Brigid Bergin: We can hear you loud and clear.

Brian: Great. Anyway, I started using Temu a while ago. My daughter's not in New York, so I was able to send her sorts of packages and all sorts of little tiny things like pins and stuff. Some of the quality was good, some of it wasn't. Then of course, there were the congressional hearings in May of this past year, was it May or June, in which both Shein and Temu were accused of not being transparent about their supply line, and were accused of using forced labor. My daughter was no longer interested in getting things from Temu, and I have stopped using Temu at this point.

I never used Shein before. I think the race to the bottom in terms of pricing has clear negative aspects. It certainly does in terms of safety protocols at Amazon warehouses, but this is beyond that. This is the question of where are these things made? There are also issues-- I'm speaking on an iPhone so that there are issues with Apple and Nike as well, but they're new places and they're not being transparent about anything.

Brigid Bergin: Brian, thanks so much for that call. Amanda, this conversation about the labor practices you touched on, but is that something that you're seeing more coverage of and more concern from consumers about as they start to get to know these companies a little bit better?

Amanda Mull: Yes, I think definitely this is something that I've seen more coverage on and I've seen more questions about, just from regular people who are trying to figure out if they should use these websites and how exactly these prices are so low. When you see a really low price for anything, whether it's on Temu or Amazon or in a store in your local community, that has to give somewhere in that supply chain whether it's manufacturing or shipping or materials or safety protocols. Somewhere something happened that meant that a significant portion of the price could be knocked off. In a lot of situations that is in labor.

That means that forced labor, very, very low wages, really long hours, sweatshop conditions are somewhat rampant, not just for Temu and Shein, but all over our consumer market.

They are necessary honestly for the system that we've created that just requires so much abundance and such low prices. Instead of buying fewer things that are more expensive, people understandably want to make their money go as far as it can. There are just trade-offs for that. We live in this system that requires all of these abuses and all of these horrors and all of this degradation to our environment and to people.

I think Shein and Temu definitely seem to be trying to take this system to its most logical extreme. I think it's pretty safe to say that this system that they've adopted and that Amazon helped create, honestly, is more dependent on this process than probably any other retailer that I can think of personally or that I've reported on.

Brigid Bergin: Amanda, you quote a Bloomberg piece that raises concerns about Temu's rise possibly leading to Americans accumulating "Chinese piles of junk." Not only is this a bit tone-deaf, but you also note that it's a bit late. How long have Americans been accustomed to consuming goods in this way?

Amanda Mull: Right. It struck me as funny in a dark way that this concern was being raised in those terms right now because it's retro for decades since outsourcing began in the '90s and then really accelerated in the early 2000s, or I guess, I mean, some outsourcing started in the '80s. We have seen this transition in the consumer goods that people buy are more and more from other places. They're from China, they're from Vietnam, they're from South America, they're from Korea, all over. Wherever there is inexpensive labor and lacks environmental standards, there are companies looking to move manufacturing there in order to manufacture things cheaper because all of those things go into the ultimate pricing of the products that we buy.

This has been going on for decades. Chinese junk, or cheap Chinese junk as Bloomberg called it, has been at the top of American Christmas lists for, since the '80s, since the '90s. This is a phenomenon that is not brand new. I think that it unsettles people that so many Americans have suddenly become comfortable buying directly from Chinese companies, that we're no longer seeing the universal need for an American mediator, which is what Amazon is. That unsettled some people who think that that makes America less powerful or America less influential in the world. Maybe that is an indication of our changing economic place within the global economic system, but that process has been in the offing for decades.

Brigid Bergin: We have a listener who texts a question, the listener writes, my main concern with products from Shein and Temu is the risk factor for contamination. I feel like a lot of things on those sites have lead or heavy metals due to the price point. Do we know if this is the case? I would assume that those companies would deny it. Have you found any of that out in your reporting, Amanda?

Amanda Mull: Those companies do deny it. When reporters have contacted them with more pointed questions about materials usage and contamination and potential safety issues, they say that we hold our sellers to a high standard and yada yada yada, which is what every company says. That's what Amazon says. That's what pretty much any retailer that imports products is going to tell you. The reality of the situation is that when you're dealing with a really large scale of products, there are going to be lots and lots of products that are just not made up to safety standards that you hope they will be made toward.

Especially when you're looking at a business model like Temu or Shein, where a lot of those products are shipped directly from China to American customers, they receive a different amount of scrutiny than they would if they were imported as wholesale lots that were then going to be stored in a warehouse here and sold by an American retailer. The import controls are different, the level of scrutiny is different. I think that you're definitely at an increased risk in buying from these companies just because of the regulatory differences and because of the inherent scale.

I think that Amazon still has some risk of that as well, because they can't inspect every single one of their products. I don't think that they want to, I don't think that that is a level of involvement in their third-party sellers that they are looking to have. When you buy at this scale and from the layers of middlemen that take different types of responsibility and shirk other duties, you're always going to be at something of a risk of contamination or safety issues.

Brigid Bergin: Gregory in the Bronx has another issue that I think he wants to raise about purchasing items from Temu. Gregory, you're on WNYC.

Gregory: Yes. Good morning ladies. Also on Shein first, a few months ago, Shein was in the news because designers, western designers outside of China were quoted saying that they had seen, as soon as they would come out with new designs, this is a matter of intellectual property theft, they would see products on Shein's website matching their designs pop up, and they weren't at all consulted or compensated by Shein.

For Temu, personally, I do a lot of shopping online from sources large and small, and pretty much, well, I don't know, several months ago, I've been hammered by ads from Temu for everything that I shop for, and the prices are attractive. I decided, let me look into it, and the information is available out there for anyone to look up online. They have a number of issues, some that were cited by your panelists, but also that-- in relation to your credit card and your information, once you submit it, that's it. You can't just try to purchase from them. You've given them your credit card information, they have it, and there have been questions of identity theft with Temu.

Once I read that, I knew that that's not for me and I just refused to even think about it. I wish I could just block them out from all the ads, but like I said, I get hammered. Every time I make a purchase of one thing, I get variations of the same thing all from Temu. More than 90% of what pops up in my searches after that come from Temu.

Brigid Bergin: Gregory, thank you so much. Those algorithms get us every time. Amanda, Gregory raises the concern about potential identity theft. Is that something that you have seen or reported on or seen in the reporting you've done?

Amanda Mull: It's not something that I've reported on personally. What I would say overall is that anytime you're dealing with a company that is clearly looking to skirt certain types of regulations that might be located overseas, we already know that part of this business model, especially upfront for these companies, is to be able to skirt import rules and import taxes and things like that because of this loophole in import rules if you're sending directly to a customer. I think that the lack of transparency overall on these companies is a problem, and that goes all the way down to data storage and the safety of your personal data, which is a concern across the internet.

Whether or not you're dealing with an American or a foreign retailer, but a retailer that's located overseas is going to have some extra layers of opacity that are going to be more difficult, I think, to sort your way through just by the virtue of different types of bureaucracy that you'd have to deal with. I think it's definitely a good idea to keep those things in mind no matter where you're shopping.

Brigid Bergin: I want to underscore another point that Gregory made and it echoes a message a listener texted us, and that's related to intellectual property. The listener writes, as a local accessories maker who has had their work knocked off by Shein, please just know, folks, shop with real people. Listeners, that's one of your fellow listeners asking you to go local. We're going to go for one more caller. Let's talk to Emma in Woodland Park, New Jersey. Do you have a question, Emma?

Emma: Hello.

Brigid Bergin: Hi, Emma. You're on WNYC.

Emma: Hi. I--

Brigid Bergin: Oh, Emma, I think we're having-- Oh, Emma, let's try that again. Are you there?

Emma: [inaudible 00:28:12]

Brigid Bergin: Emma, I'm sorry. I think we're having some trouble with your line. Go ahead, Amanda.

Amanda Mull: One thing that I did want to say about the intellectual property issues and the rip-off issues is that the thing that these websites, and Amazon to a great extent as well, but Shein and Temu especially, something that they don't have is any kind of creative vision, any kind of imagination of their own. They don't employ, really, people who are in charge of that. What they do is fundamentally reactive, so it's going to feed off of the creative energy of other people, of things in their surroundings.

The question of inspiration is something that creative industries deal with all the time, but because fundamentally, these companies are looking to exploit logistical efficiencies, when you're buying products from them, you are always buying products that are the result of somebody else's good ideas and interesting thought, and the risks that they've taken creatively or economically, and in situations where you can, it's always better to try to find that source material and patronize those people who are out there making interesting creative work.

Brigid Bergin: Let's try Emma in Woodland Park, New Jersey one more time. Emma, are you there?

Emma: Hi, can you hear me?

Brigid Bergin: We can hear you. What's your question?

Emma: Wonderful. I heard you talking about this new societal system we have in place where it was phenomenal now that we're able to shop online. I was wondering if a main contributor to Amazon being this titan of online retailing is the prime factor in which you can receive these items in sometimes even the same day, whereas with something like Shein, it could take a week, two weeks, a month, or you might not even ever receive the package reliably.

Amanda Mull: I think this is a fascinating question, because definitely the rise of Amazon, a lot of that is attributed to the fact that their prime shipping program is so good that you can get things in a day or two, that it's very reliable, that you can send anything back that you want. I think that that program and those policies broke down a lot of the mental barriers that people had about shopping online, because 20 years ago, when this was a much newer technology and it was less normal to buy shoes and underwear and couches and things that you have to physically interact with in a pretty intimate way on the internet, retailers wanted to make it as similar as possible and as risk-free as possible as getting something in person and trying it on and deciding you don't like it.

That really drives a lot of people to those websites in the first decade or so of online shopping and it's what helped to create a lot of loyalty to Amazon. Now, there's some research just starting to suggest that people are like, "Well, I don't really need most of what I order in a day, in two days. If I can get something for half price, but I have to wait two weeks, well, I didn't want to use that today anyway, and it was just a thing I was curious about. Yes, two weeks is fine. We'll see if it shows up."

I think that when you drive prices as low as Shein and Temu have, and when you have a populace that is used to the quickness of online shopping and has begun to figure out when it is not so important, I think that you end up with a lot of people who are like, "Well, I'll give it a try. I'll forget I bought the thing in two weeks and it'll be like getting a little surprise."

Brigid Bergin: [laughs] Just for our last question, Amanda, you've touched on this a little bit, but can you explain what separates Amazon from Temu right now? You write about it as the veil of Americanness. What do you mean by this? Is it enough to keep Amazon going?

Amanda Mull: For much of its history, and especially for the 23 years or so that Amazon has had this third-party marketplace system in place, a lot of sellers, of course, on Amazon, are from overseas. If you shop on Amazon and try to read product descriptions now, it's inescapably the case, because a lot of that stuff is very obviously translated or not written by a fluent English speaker. You've got a lot of indicators in your shopping experience that you're transacting with people who aren't in the US. For a long time, that was something that scared people about online shopping, that it seemed less trustworthy. It seemed like it was going to take a long time. It seems like you might not get what you were paying for.

I think that Amazon, because of its own brand recognition and how much people like Amazon as a retailer and rely on Amazon, I think that it has spread its halo of goodwill among its users to all of these international sellers. It's become less and less important for the millions of people who shop on Amazon to have this illusion that they're buying from another American. People have stopped caring because they're used to the experience and it's fine. They're fine with it.

I think that that Americanness of the experience of shopping on Amazon, when that begins to slip and people become okay with the idea that they're buying something from somebody in Guangzhou or somebody in Shanghai and those transactions go okay for them, then I think that creates an opening where sites like Shein and Temu, that are obviously not American, to woo customers in a way that wouldn't have been possible if Amazon hadn't extended its halo of Americanness to all of these sellers for the past 15 years.

Brigid Bergin: It's so interesting. Amanda, thank you so much. We're going to leave it there for now. My guest has been Amanda Mull, Staff Writer at The Atlantic. Her most recent piece is called, Is this how Amazon ends? Amanda, thanks for joining me this morning.

Amanda Mull: Thank you so much for having me.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.