[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC, we will end today by talking baseball. The new rules that have significantly changed the game now that the first season with those rules is about a third of the way done, and about baseball books that indicate to our guests that the crisis that caused baseball to change the rules is only the latest in a long history of a game that is beloved by many, but seemingly always in a state of crisis of one kind or another.

Our guest is Patrick Sauer, writer and co-host of the live online talk show, Squawkin’ Sports, and he has a Washington Post article that reviews three new books about baseball that all make his point in one way or another, I think. His article is called Varieties of baseball: New, old and bananas. Patrick, thanks for coming on. Welcome to WNYC.

Patrick Sauer: Happy to be here, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start with the new rules, then we'll get to the new books. Major League Baseball games are meaningfully shorter this year because of a new pitch clock. You have to throw the next pitch in most cases in 15 to 20 seconds, and the batter has to be ready. Do you like the change?

Patrick Sauer: So far I do. I looked up just before I came on here. If you take three of the major changes, the games are currently 28 minutes shorter, which is significant. Batting average of balls in play basically balls that aren't hits instead of strike walkouts or home runs are up, stolen base attempts are up 1.3 a game to 1.78, and the success rate is almost 80%. The changes are working. I would say it was most noticeable to me going to a game at City Field. It was a game with a decent amount of offense, but my daughter and I were able to get from Brooklyn to the stadium and back in under four hours, which never happens. On that simple point, I think it's great.

The game had gotten too long, stagnants too many, and part of it things that aren't that important to baseball, stepping off the mound, stepping out of the batter's box, walkup music. I think some of the nips and tucks here have really helped. Stolen bases are fun, triples are fun. From that standpoint, I would say yes, I think there are unintended consequences that have probably not been thought through. There are reports of pitchers already burning their arms out quicker, which was already a huge problem because they've been sped up and even though this has been in the minors for a few years, those guys have some taste of it. There was a full steam ahead all of a sudden without-- I'm not sure that it has entirely been thought through.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, interesting.

Patrick Sauer: From a fan perspective, I think it's better.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we're going to invite texts for this short segment with Patrick Sauer. Do you like baseball better now that the new rules have been implemented? Give us a text, not a call for this segment, but it's the same number, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. I wonder if anybody thinks that younger people are being more attracted to watch the game of baseball, which I think is the point because of this already, maybe it's too early to tell.

Listeners, text your reaction to the new rules in baseball to 212-433-WNYC, that's 212-433-9692. I guess the other thing I'd ask about your take on the new rules is the other one is they banned the shift, that is playing fielders mostly on one side of second base, which critics think had resulted in much less interesting situations. I always wonder how it took 100 years for them to figure out that the shift was statistically the most effective defense because this massive trend toward shifting only started a few years ago. How did it take them 100 years to figure it out? It only took us a few years to figure it out that it made the game boring.

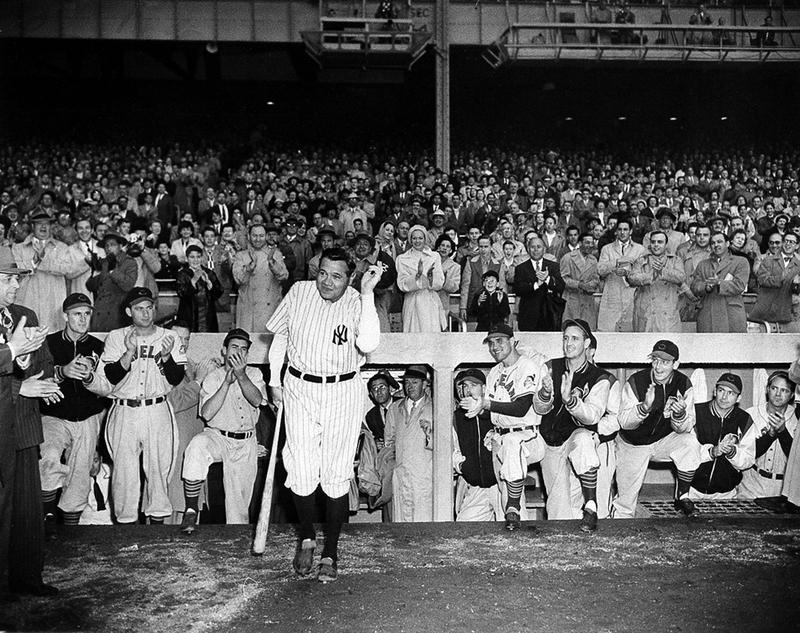

Patrick Sauer: [laughs] Well, I will actually correct you on this. One of the books in this story is called Baseball at the Abyss: The Scandals of 1926, Babe Ruth, and the Unlikely Savior Who Rescued a Tarnished Game at the time. Going back to 1920, teams did use the shift against Babe specifically including one team that put their first baseman into shallow rights. Babe being Babe, just learned to hit the other way. It didn't last that long. I don't know if it was effective in the way that it is now.

Yes, as part of a mass strategy, I think it's because when it became a game of what they call three true outcomes, a walk, a strikeout, or a home run, meaning a ball that the defense doesn't have any say over, the batter started raising their launch angle, which is trying to hit the ball out of the park. If you're not hitting ground balls play as much, you're going to have more pole hitters, lefties in particular. I believe it was the Rays that probably started most interesting offbeats, thinking seems to come out of Tampa for some reason.

They began shifting probably against the Yankees, if I had to guess, and it works. The thing is it works and while it seems cheap, we can get into the book that's most important to this conversation, The New Ballgame by a writer named Russell Carlton of Baseball Prospectus. He said part of the reason though we think that hitters are getting "robbed of hits" is because the game is presented to us from the hitter's perspective. We always think of it from the hitter's perspective. The game is shown from the hitter's perspective, but how is that any different than if you look at it from a fielder's perspective?

Baseball has taken away the ability to make outs, which is their primary job, so it's their only job. I don't know why it took so long to figure out that it works other than I think players use the total field a lot more until the '90s. I also do think there's a case to be made that yes, I didn't love it. It didn't look right, but on the other hand, if you are a manager, your job is to get 27 outs. If you're a fielder, your job is to get three of them per inning, and if it makes that happen easier, then it's the success, but I don't think the average fan likes the shift. Even reading this book intellectually I can get it. I don't know, I don't like looking at it.

Brian Lehrer: It's the paradox that something that can be more effective from an offensive or defensive standpoint can make it more boring to watch and then the league has to decide, what are we in this for? They chose the side of entertainment which is probably what they should do. Some of the texts that are coming in somebody writes, "I love the new pitch clock. It speeds up the game and they should have done it years ago."

Indifferent on the rules about the shift, somebody writes, "I love the slowness of the game. It is a metaphor for summer, nice and easy." Someone else, "To me, baseball's problem is that it's too steeped in nostalgia. I understand history, but to me, it feels like it's always trying to look back." Those are a few things that are coming in. Maybe that's a good jumping-off point for you to talk about another of the books that you reviewed for the Washington Post, the one called, The New Ballgame: The Not-So-Hidden Forces Shaping Modern Baseball.

Patrick Sauer: If you're just going to read one book to understand how we got here, that's basically what this book is. The writer looks at all sorts of aspects of changes ostensibly over the last 50 years, but mostly from the last two decades. It explains a lot of things that people complain about rightly and wrongly. For me at least, the book has me thinking about the game differently or at least acknowledging that some of these things are not outlandish, even if they're not maybe as aesthetically pleasing as one might hope.

Here's a great example. He talks about the difference between something that's good for A game of baseball versus D game of baseball. Starting pitching is a great example. Historically, every time a pitcher goes through the third time through the order, and this is not just recently, that he goes back to the '70s for this, the offense has an advantage. If the idea is that pitching is a shared effort, if you look at pitching as a shared effort of your pitchers, you can take even out reliever starter, and if the job is again, to get people out as a communal effort as a team, then there's not really any reason to have a pitcher go more than six innings.

It just doesn't make any sense statistically. That being said, who doesn't like watching a complete game, 120 pitch complete game with a warrior out there staggering around on the mound, just trying to get these last outs because that's the thrill of sports, even if logically it doesn't make a lot of sense. The last live event we had with Squawkin Sports, author of a different book called Road to Nowhere said, "The difference is though watching one guy strike out 14 batters is fantastic. Watching five guys strike out 14 batters is boring."

Brian Lehrer: Interesting way to put it. I guess the question that you probably can't even begin to answer now is will it "save the game" in terms of interest to the next generations? Baseball, which used to be the national pastime, is not the number one sport anymore. We could argue that baseball doesn't have the violence of football, which disgusting as it can be at times is attractive to a lot of people to watch. It doesn't have the big personalities that pro basketball has and with the slowness. We don't live in an agrarian pastoral country anymore. The conditions under which baseball is invented, does it have a future? Does this change the future? Speeding up the game in these ways? Do you have an opinion about that?

Patrick Sauer: I have a mixed opinion on that. I also want to add one thing about the NFL or college. I think people underrate how easy it is to be a football fan. It's just three hours a week. Fantasy football is a lot easier to play and it's a much easier sport to bet on. I think sometimes that is a simple part of it. You give up half your Sunday, it's cold outside anyway. As far as the pace of game and that, I don't know what the answer is because whoever texted said they like the slow pace. I think there's something to be said for slowness but not stagnation. Sometimes those are just run parallel. I don't know if young people are going to come back to baseball in the same way.

I believe it was 5% of a 2020 pole, people under 45 said it was their favorite sport to watch. It is going to be passed by soccer. I am certain of that. Also part of me thinks people's tastes change. Baseball's not going away. If you like baseball there will be baseball. I think that cool factor, that it factor is nebulous and somewhat overrated. It's not going to be the NBA. The game doesn't work the same. I think they have a big problem minting superstars.

Brian Lehrer: Even if it's the number three or number four sport, it's going to be there for people who like it. We thank Patrick Sauer. His online talk show is called Squawkin Sports, and he reviewed three new books about baseball for the Washington Post. Thanks so much for joining us.

Patrick Sauer: Thank you and let's go Mets.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.