COVID-19 Vaccine 101

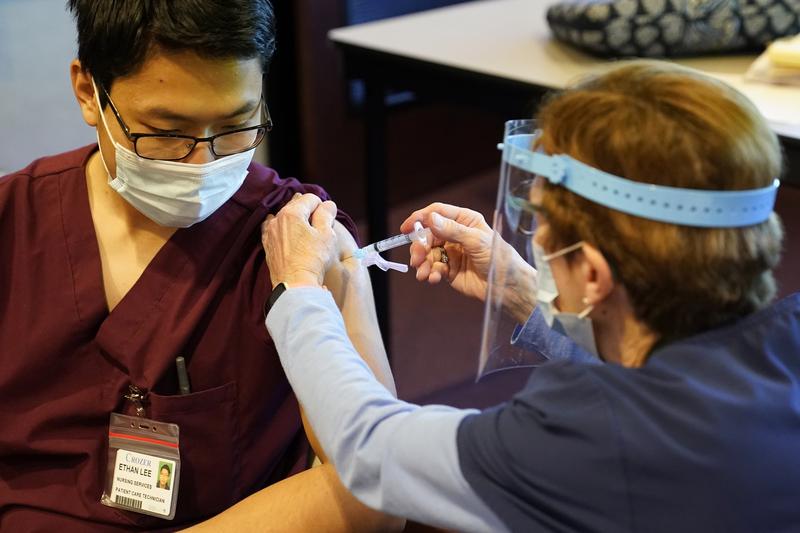

( AP Photo/Matt Slocum )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, again, everyone. Now, vaccine expert Dr. Ruth Karron from Johns Hopkins University to answer your vaccine questions and dispel some vaccine myths. You can call with your questions about the COVID vaccine at 646-435-7280. 646-435-7280 or tweet a question @BrianLehrer. It's clear that while many Americans are scrambling to be the next in line to get vaccinated, people also have questions and people have doubts. For example, last week, Ohio governor Mike DeWine gave us this disturbing fact.

Mike DeWine: Anecdotally, it looks like we're at somewhere around 40% of staff and nursing homes is taking the vaccine, 60% are not taking it. Again, it's my message today, just urging people not to compel anybody to do it but urging people to take that vaccine.

Brian: Governor Mike DeWine, last week. Earlier this week, a pharmacist in Wisconsin was arrested on charges that he, "Intentionally sabotaged more than 500 doses of the COVID-19 vaccine." The New York Times reported he was "An admitted conspiracy theorist" but 60% of the nursing home staff in Ohio and that one lone pharmacist in Wisconsin are not the only ones skeptical of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines, recent surveys by Pew and Gallup found that only 51% to 58% of respondents said they would get a COVID-19 vaccine. Well below the minimum 70% threshold needed for herd immunity.

Joining me now to explain how the COVID-19 vaccine actually works, to dispel some of the myths out there, and to answer your questions, and boy do you have questions, our lines are already full is Dr. Ruth Karron, professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Director of the Center for Immunization Research, and founding director of the Johns Hopkins Vaccine Initiative. Dr. Karron, thank you so much for your time today. Welcome to WNYC.

Dr. Ruth Karron: Thank you, Brian. It's good to be with you.

Brian: What's a vaccine?

Dr. Ruth: A vaccine is a substance that we inject or occasionally give, say, by nose drops or orally to produce an immune response in the body that is comparable to the immune response you would get from natural infection or in some cases, even better than that immune response. It's devised to protect you against infections, against germs.

Brian: Both the Moderna and the Pfizer vaccines use messenger RNA or mRNA. People have been seeing those initials and probably don't really know what they mean or if this makes them different from the measles vaccine or the polio vaccine or what you might get as a kid. What is mRNA, how does it work in the body, and is it unique to COVID?

Dr. Ruth: mRNA, as you said, does stand for messenger RNA. It's what helps the body, it's what tells the body how to make proteins. We have many messenger RNAs in each and every one of ourselves. The way it works, it is different from vaccines that we've had licensed before. It's not alive viruses. For example, measles is. It is injected into the body and it goes into the cells and it tells the cells how to make, in this particular case, the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 which is a protein that induces protective immunity in people. It tells the cells how to manufacture this protein.

mRNA vaccines, we haven't had them licensed before but we didn't start-- WE, and I mean the big WE, the collective WE, the world didn't start working on mRNA vaccines in January from scratch. There's been a lot of work that's gone on before this time. Actually, there have been no mRNA vaccines licensed, but a few that have been tested, for example, against influenza. The technology is not brand new but it was newly used to combat this disease.

Brian: Let me ask you the most common skeptical question that I've been getting and that is, based on the newness of the mRNA technology, how do we know that there aren't going to be long-term negative side effects from the vaccine? We can tell at this point that there aren't many short-term side effects because so many thousands of people have now been vaccinated and they've just been the very small handful of serious allergic reactions which have been treatable. How do we know that there aren't long-term effects?

Dr. Ruth: I would say that there is no reason for us to think that there are long-term effects for these vaccines that are different from any other new vaccines. We have information, as you said, on the short-term. There's no reason, the mRNA doesn't persist in the body indefinitely, it doesn't go into the cell nucleus or it's RNA, it's not DNA, it doesn't change your genes. It can't change your genetic material.

We do for all newly approved vaccines, we will have long-term follow-up, and one of the mechanisms that exist there, there're existing mechanisms for long-term follow-up but there's one specific for COVID vaccines which is called V-safe, which is run by the CDC. It's an app-based platform for people to report adverse events. We will follow these vaccines as we follow any new vaccines for a period of time but there is no reason for us to think that we would have any more long-term effects than we might observe with any new vaccine.

Brian: Lisa in New Rochelle, you're on WNYC with vaccine expert, Dr. Karron. Hi, Lisa. Lisa in New Rochelle, are you there?

Lisa: Oh, hi. Hi. Sorry. I recently was diagnosed with COVID and want to find out if I should get the vaccine or if I'll be required to get the vaccine.

Dr. Ruth: Yes. Thank you for that question. The current recommendations, yes, you should get the vaccine is the short answer. The current recommendations for the CDC is that you wait a period of 90 days before getting vaccinated. The reason that we say you should get vaccinated, ultimately, is that there is evidence that these two vaccines, the Moderna vaccine, and the Pfizer BioNTech vaccine actually induce better immunity, higher titers of antibody than you might have after a natural infection. There's some notion that perhaps you might be protected for a longer period of time or have better protection against severe disease with vaccination. The current recommendation, again, is that yes you should get vaccinated but that you should wait at a period of 90 days.

Brian: Can an individual test their titers sometime after getting vaccinated? Can the individual know a few months down the road or even just a few weeks down the road after the second shot if they are really immune as an individual?

Dr. Ruth: I would say a couple of things about this. One is that we don't today have what's called a correlative immunity. What I mean by that is that's a number where we can say hard and fast, let's call it an amount of antibody where we can say, if you have this amount of antibody, we know you're protected against SARS-CoV-2. We know that these vaccines work and they work extremely well but there's no particular number that tells us that. Yes, you could commercially get your antibodies tested.

I would just say that some of the commercial antibody test measure antibody to the spike protein which is what's in the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines. Some measure antibodies to other proteins which are not in those vaccines. It's possible that you could even have a negative antibody test if the particular commercial assay doesn't measure antibody to the spike protein, but either way it will tell you that you have antibody but it won't tell you how much, and we don't know even if it did tell you exactly how much is needed for protection.

What we do know is from-- These are large studies, far larger studies than we often do to license vaccines, we do know that people who receive these vaccines are protected, not only against serious disease, which is what we especially hoped for, but the protection against any COVID disease with both of these vaccines is remarkably good.

Brian: Frederico in Manhattan. You're on WNYC with vaccine expert, Dr. Ruth Karron from Johns Hopkins. Hi, Frederico.

Frederico: Hi. Brian, my first cousin is a 75-year-old man that has a bunch of health issues. He's had a liver transplant in the last five years. The doctors seem to say that it's okay for him to get the corona vaccine, but I'm concerned because perhaps the liver as an organ of filtration may not be able to handle this new vaccine. What does the doctor think?

Dr. Ruth: I don't think that-- The way the vaccine works wouldn't really involve the liver. I wouldn't be concerned about his body's ability to handle the vaccine based on his liver disease issues. I think something that he should discuss with his doctor is how immunosuppressed he is because of this transplant. I don't know the answer to that, and not so much from the perspective of whether the vaccine would be safe as from the perspective of whether the vaccine would be effective. If he is getting medication to suppress his immune response, it's possible that he wouldn't develop antibodies to the virus just because of the drugs he's taking. That's something probably that he should discuss with his physicians.

Brian: Frederico, thank you. On the topic of myth-busting, the conspiracy theorist, who I mentioned at the beginning of the segment, the Wisconsin pharmacist who sabotaged 500 doses of the vaccine in a hospital, believed that the vaccine could change people's DNA because it's an mRNA-based vaccine. According to the police report, that's what he said. It could change people's DNA. That's what he was afraid of. We've heard that repeated by others. Why do you think people think that, and what would you say to them?

Dr. Ruth: I think people think that because this is a nucleic acid vaccine, and we tell people that, and I think particularly in the early days of our description of this vaccine, people would say what's a nucleic acid and we would say, well, RNA is a nucleic acid and DNA is a nucleic acid, that sort of thing. RNA, mRNA does not enter the cell nucleus. The cell nucleus is where all your genes are. It cannot change your genetic code, your genetic material. This is, as you say, Brian, this is a myth to bust. This is something that just has no basis in science or in fact.

Brian: Marge on the upper Eastside, you're on WNYC. Hi, Marge.

Marge: Hi, Brian. My question is about herd immunity. I keep hearing that, at least for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, that it will protect you from getting a severe disease or getting sick from the disease, but it will not protect you from getting the virus and therefore spreading the virus. Since my understanding of herd immunity is that when enough people have it, the virus has nowhere to go so it can't spread. I am having trouble understanding how you can have herd immunity if the virus can still spread.

Dr. Ruth: Thank you. That's a great question. I would maybe just modify a bit what you said, which is to say, we don't know whether these vaccines can prevent spread. We don't have data one way or the other. That is not to say that they can't, that is just to say that we don't know and because we don't know, we have to act as cautiously as possible. What does that mean? That means that once you're vaccinated, you don't throw away your mask, you don't stop social distancing, you don't stop all of those non-medical interventions that we're all doing right now to stop the spread.

We will find out, we will get more information over time about the ability of these vaccines, as well as other vaccines in the pipeline to prevent the spread of the virus. I would say that right now, really in terms of herd immunity, what we're relying on is that each person would have enough immunity themselves, that that would prevent them from getting sick with COVID but I don't think--

I think, first of all, the numbers that we're tossing around for herd immunity are at best speculation and they may change as we get viruses that are more transmissible. We've all been hearing a lot in the last week or two about viruses that may be more transmissible, and we may need more people to be immune to stop the spread of those viruses. For right now, until we know more, we need to really rely on every person having their own immunity against this virus.

Brian: Even if it doesn't prevent the spread, people would still want to take it because if-- In a way, we're all sharing germs with each other all the time that we don't think about because they don't get us sick. If these become germs, if germs is even the right word, but they don't get us sick, then it doesn't matter.

Dr. Ruth: That's right. I think that's a really important point. It's important for two reasons. One is that we talk about preventing transmission as an all or nothing phenomenon, but that might not be true. It could be that it lessens transmission and that's an important feature in and of itself, but also as you say, Brian, even if the virus is transmitted and can replicate in your nose, but you have immunity such that either you'll be asymptomatic or maybe you'll have a runny nose or something, but you won't have any kind of severe disease, we would still consider that a good outcome, exactly

Brian: Lindsay and Randolph, you're on WNYC with vaccine expert, Dr. Ruth Karron from Johns Hopkins. Hi, Lindsay.

Lindsay: Hi. Thank you guys so much for having my call.

Brian: Sure.

Dr. Ruth: Sure.

Lindsay: I am currently 25 weeks pregnant and a healthcare worker. I am eligible in my state to get the vaccine and actually have an appointment on Friday. There are super limited data on pregnant women getting the vaccine. I was just curious as to your thoughts about pregnant women getting the vaccine and what the potential risks and benefits are to that.

Dr. Ruth: Thank you for that question, Lindsay. I think it's a question that probably many people and maybe many of the listeners here have. What I would say is that unfortunately, we don't yet have a lot of data from studies in pregnant women for either of these vaccines. We do have some data. There were women in the trials who the trials did not include pregnant women, but there were women who became pregnant in the course of the trials. Just a very small number for each trial.

We have not seen any adverse outcomes from those studies, but again, those are very small numbers. I'm sure that you've seen the statement from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology which is somewhat helpful and that it goes through some of the considerations, but at the end of the day says, of course, this is a decision between you and your healthcare provider. There is not evidence that mRNA can harm a pregnant woman or harm the fetus. We do not have that kind of evidence. There is not theoretical reason to think that this product would be harmful.

There are side effects of these vaccines that pregnant women might particularly want to note and fever is something in particular. I believe ACOG has recommendations around pre-medication for fever, considerations around pre-medication for fever particularly in the case of pregnant women. I can tell you, interestingly, of course, recommendations for pregnant women vary in countries. In the US, we have what's called this permissive recommendation.

The UK, Great Britain has recently changed its recommendations, they initially recommended not using the vaccine in pregnant women. They're now saying that pregnant women who are on the front lines, for example, because they're healthcare workers should consider using the vaccine much as we are saying in the US. In Israel, pregnant women are being prioritized for vaccination. There are many pregnant women who are because of their risks, the risks of COVID in pregnant women, pregnant women are at greater risk of serious disease from COVID than non-pregnant individuals. That is why that population is being prioritized in Israel right now for the Pfizer vaccine and likely will be the same for the Moderna vaccine.

Brian: Tom in Morristown.

Dr. Ruth: I don't know if that helps.

Brian: Lindsay, I hope that helps. I think it probably helped a lot of people a lot. There was definitely some new information in there for me. Probably for a lot of others too. Tom in Morristown. You're on WNYC with Dr. Karron. Hi, Tom.

Tom: Hi, thank you very much. I'm 75 years old and I'm still full-time employed working in various multiple hospitals, servicing diagnostic imaging equipment in emergency rooms and radiology departments. Now this Pfizer vaccine, they say is less effective in older adults, but it's available for me to get. My question is out of safety and fear that the AstraZeneca vaccine, they said in the high dose administration would be more effective in older adults. If that becomes available to me later, would it make sense for me to get that later in addition to the Pfizer, or would there be a contraindication for multiple vaccines? I'm just concerned of safety and fear of getting this stuff.

Dr. Ruth: I would just say that I'm not completely certain about the data that you're citing for the Pfizer vaccine. Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines were shown to be highly, highly effective across all the age groups in which they were studied. There wasn't, there was not a decrease in efficacy. The AstraZeneca vaccine is still under evaluation. I think it'll be important for us to be able to see the data from the US for what is considered the full dose of the vaccine. That's data that's still not yet available to us because those trials aren't completed.

I would suggest that if you have access to either the Pfizer or the Moderna vaccines, you should receive them. You should assume that it is likely that you will be afforded the same protection as was seen in the trials for people in your age group.

Brian: Good luck, Tom. Thank you very much. As we start to learn at a time, what do you think you're up against here? With 30% at least of the population so far saying they don't want to take it, 60% of the nursing home staff in Ohio, according to the governor of Ohio in the clip we played at the top. Back in May, a YouGov poll of 1600 people reported that 28% of Americans believe that Bill Gates wants to use vaccines to implant microchips in people. That figure Rose to 44% among Republicans.

It all started in March when Bill Gates said in an interview that we will have some digital certificates, used that term eventually, which would show who had been vaccinated according to the BBC. A, can vaccines inject microchips or nano transducers into our bodies. What are you up against in terms of false conspiracy theories that sound plausible to people?

Dr. Ruth: The first question is a whole lot easier to answer than the second one. No, these vaccines don't have microchips and that's not what's being injected into people. I think that the statement was misinterpreted. Everybody will get-- Everyone who is getting COVID vaccines gets a certificate. There are paper versions of those. There are also electronic versions of those that can be printed. That fact somehow got spun into microchips, but that is simply not true. I think that people who are vaccine-hesitant as we describe it, are vaccine-hesitant for a variety of reasons.

There are some people who are hesitant about all vaccines and there are some people who are hesitant in particular about these vaccines, and they're hesitant, and for that population, those people are hesitant in part because these vaccines were developed so quickly. They're hesitant in part because this past year, people have been concerned about government agencies perhaps pushing vaccines through prematurely. I think that we've certainly seen on the part of the FDA, really very clear guidance on what we would need to approve a vaccine under EUA. They've been absolutely open, transparent, clear, and not driven by politics and in their processes.

I also think that one important thing for people to understand is the reason we were able to move so quickly is that we invested, you and I and the taxpayers and our government invested in large scale trials. We did trials in 30,000 people or 45,000 people. That's many, many more people than we're able to typically enroll in a vaccine trial and part because of resources.

What that meant is two things. One is we were able to get our answer quickly about whether these vaccines worked because the more people you test them in, the more quickly you can get to that answer. The second thing is that we were able to assess safety in large numbers of individuals. 30,000 to 45,000 is somewhere between 5 and 10 times the number of people usually in studies. We have a much larger and better, if you will, safety database to examine.

The other thing I will just say is, I think what's important for people to understand is it is vaccination that is going to allow us to get back to those things in life that we enjoyed and for different people, that means different things, but it is vaccine that will allow us to get back to some semblance of life as we knew it. I think that as people come to understand that, and as people, even though there were 30,000 to 45,000 people, we now have millions of people who are vaccinated. As people continue to see that happen, and as they think about how they want their lives to change for the better, my hope is that some of this hesitance will dissipate.

Brian: Dr. Ruth Karron, director of the Center for Immunization Research at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and founding director of the Johns Hopkins Vaccine Initiative. Thank you for answering so many questions. There are so many more, there are so many people waiting on hold with more questions that I hope we can have you back and do round two at some point in the near future. Thank you for today.

Dr. Ruth: Thank you so much.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.