COVID-19 Cases and Deaths Climb in Brazil

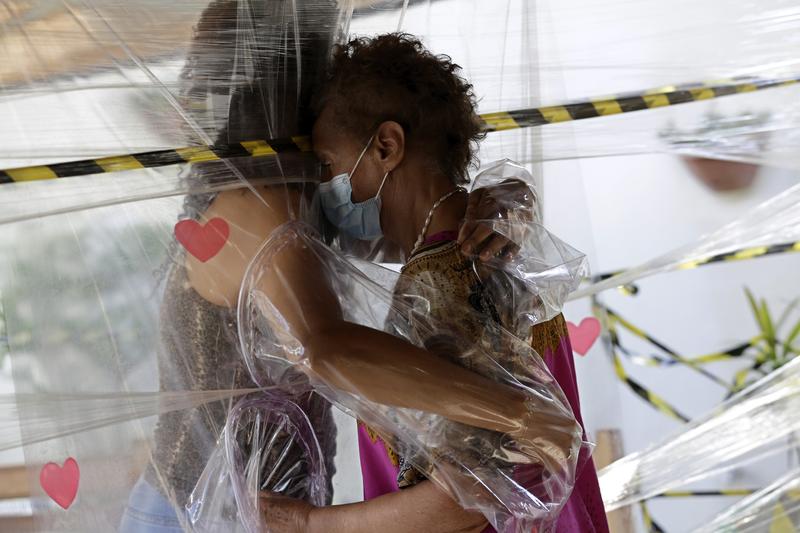

( Eraldo Peres / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC, and now the Brazilian variant as seen from Brazil. The start of 2021 has been exceedingly grim in Brazil, to put it bluntly, with more than 325,000 total coronavirus deaths. Brazil has the second-most COVID-19 deaths of any country behind, yes, the United States. As it stands, the country's recent daily COVID death toll is dismally close to 4,000, which makes it the highest number of daily deaths of any nation at the moment, and several times what we're experiencing in the US right now, even as deaths remain stubbornly high here.

Brazil is the global epicenter of the coronavirus pandemic right now. Hospitals are on the brink. Vaccines are conspicuously scarce, and converging crises threatened to worsen a situation that is already untenable. Medical scientists in the country warn that the uncontrolled spread of the virus could lead to additional Brazil COVID variants besides the one already spreading there, and here, and elsewhere, and threatened to extend the course of the pandemic globally, but so far Brazil's government response has been marked by inaction and mismanagement, and very reminiscent of Donald Trump in the downplaying and denial of the virus by their president, Jair Bolsonaro.

With me now to put all of this into some context is Margareth Dalcolmo, doctor, pulmonologist, professor and clinical researcher for the Public Health National School of the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, it's all known as Fiocruz, in Rio. Dr. Dalcolmo, thank you so much for your time today. Hello, from New York, and welcome to WNYC.

Dr. Margareth Dalcolmo: Hello, Brian. Very good morning and since now is, a Happy Easter if you can, for you all. It's very difficult times. It's very difficult, even for us doctors to say Happy Easter, but at least the peaceful days, this is what I wish you all.

Brian: Thank you and I understand. I gave some headlines from the news accounts there. How would you, with your involvement, begin to describe the situation further in Brazil to an outsider?

Dr. Dalcolmo: The summary you did provide is correct. The figures you did mention are also correct. The situation we are living actually these days in Brazil, the worst moment of the pandemia since the very beginning. There are some facts or milestones that it's worse to be mentioned, Brian. Since the very beginning of the pandemic in Brazil, the first problem that we faced, I'm speaking on behalf of the academic community, the medical community. We didn't have, for instance, comparing with previous epidemics, that we lived in Brazil, we always lived with a central coordination harmonized between the authorities, the minister of health and the scientific community, but this time, since the very beginning, we didn't have it.

Because I did participate in the very first group of consulters from of the Ministry of Health with Minister Mandetta, who was the first minister of health of this government, and since he left, we never more had a harmonized kind of conversation and that this is a real problem. This has been a real problem. Why? Because the civil society has been confused to whom they have to comply with.

To me, Dr. Dalcolmo, that says every day on televisions or medias, that you have to keep social distancing, you have to use masks, the vaccines are the very, I would say solution for an acute viruses like the other ones, but the president and some other authorities says the opposite, and so it created a very tense and confused, I would say, environment in the Brazilian population, and the outcome of this is not good. This is the first problem.

The second problem is that we knew in this last month, Brazil has been a very good place to develop very good quality phase III trials using good vaccines like Pfizer, Johnson, AstraZeneca, and even the Chinese CoronaVac, but we did two good things. The two public good big institutes like Fiocruz and Butantan, we established tech transfers projects, and so we started to develop different projects. I have to mention, but in Fiocruz, for instance, where I work, we established a complete, a full tech transfer process, and so we started to make this submission to our regulatory agency since September. This is a good thing.

The problem is that the Brazilian diplomacy didn't work in a proper, I would say, manner with the Chinese, for it to give you only an example, and so, because of this, despite having this process already signed with AstraZeneca using its site in China, we didn't receive the raw material to produce the vaccine here in Rio de Janeiro, in Fiocruz, in a good moment, in the proper moment, and so we are late in our calendar of providing vaccines.

Brian: So the vaccine rollout is going much more slowly than in this country, where now we have almost a third of the United States with at least one shot.

Dr. Dalcolmo: Absolutely, so we need to improve the rollout of the vaccination. This is another Brazilian paradox, Brian, because you have to figure out that Brazil has a very traditional knowledge in vaccinating. The national program of immunization is recognized, and even internationally, so we know, we could be vaccinating at least two million peoples a day. Now we are reaching, in these last three days, we are almost reaching one million, almost, but in these last three days, so the rollout is too low, so it's too slow.

We have to scale up this vaccination, but for this, we need more vaccines. Following the example I did give you, that we were a good site to develop a good phase III trials, but in contrary, we didn't negotiate with this producer, the procurement to have this vaccine.

Brian: I understand, to get enough. I want to invite listeners with connections to Brazil, or those of you who have questions about the coronavirus situation in Brazil, and even its implications for here and elsewhere. We can take your calls with Margaret Dalcolmo, doctor, pulmonologist, professor, and clinical researcher for the Public Health National School of the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, or what they call Fiocruz in Brazil, 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. Especially if you are from Brazil or have personal connections with Brazil, help us report this story, or ask Dr. Dalcolmo a question, 646-435-7280. Natalia in Fort Greene, you're on WNYC. Hi, Natalia.

Natalia: Hi, Brian. First, I want to thank you very much, and thank you, Mayor de Blasio for standing with us against the Bolsonaro award in May 2019, which helped us create the Cancel Bolsonaro Coalition and we were able to cancel his visit back then. We have been protesting and part of the Defend Democracy in Brazil Committee in New York. I have relatives in Sao Paulo who are in lockdown right now, and the lockdown is really affecting the middle class, but the poor people in Sao Paulo and in Brazil they have to work.

They have not had any emergency aid from the government, and that's a very big problem. They're not able to stay at home, and social isolate, and also the vaccines are very slow in coming. The ambassador of Bolsonaro in Washington has come to Harvard this week, and lied about the campaigns and how the vaccines are going to get there in April, it's impossible. They say they have accelerated the contract with Pfizer. It's not true. I think Lula Da Silva has called for G20 to reconvene. He has asked Biden to do that. I think it's very important that we really call in the G20 leaders who have not, surprisingly, met for a global solution to the pandemic and I think Brazil needs to be included in that global solution right now.

Brian: What's your sense Natalia, from what you're hearing down there, or from down there, about how much Bolsonaro's downplaying of the virus has affected the spread?

Natalia: It has really, because right now we still don't have a mask mandate that affects the whole country. The Bolsonaro supporters have played into this wistful scenario by persecuting people who have asked for mandates and governors and local mayors, I think persecuted by haters of the Democrat or the Social Democrat leaders, or even if you're a center right wing politician, you've been persecuted if you do not agree with extreme right view of Bolsonaro, I think that's a huge problem.

We actually have a public act tomorrow in New York in Manhattan at Union Square at 4:00 PM. We call all our friends to stand in solidarity with Brazil. It is really a global threat because the variants are getting to the US, and then again to neighboring countries in Latin America.

Brian: Natalia, thank you very much. Interesting that there would be an event in New York tomorrow, as you say, to stand in solidarity with Brazilians. Dr. Dalcolmo, can I get your take on the role of the president there, if you feel free to say, in allowing the spread of the virus to accelerate?

Dr. Dalcolmo: Yes, Brian. The examples that Natalia just has just mentioned are correct. The role of the president did not help. This is something to summarize, its role, and so far he's still insisting. For instance, today he is in newspaper saying that maybe one day, after the last Brazilian has been vaccinated, he can think about to be vaccinated. This is a very bad example because Brazilians use to comply with vaccination.

We have a very, as I mentioned, a very good experience in vaccinating Brazilian people. Now, he's sort of not helping, at least, to say the least, that he's not helping people to comply with the vaccines. We are studying, for instance, Brian, a way to respond whether the two vaccines that we are using in Brazil, CoronaVac either, and AstraZeneca one, whether they did cover the new variants. So far, they are covering the P.1, which is how it's called the Brazilian variant, the SARS-CoV-2, and they are both well responding so far, but we are doing a cohort, big cohorts of people vaccinating from Manaus.

For example, in the north of Brazil, we had very heavy first wave and second wave, as you mentioned, as you know, and so we are studying this through Fiocruz. Fiocruz is a national institution, so we are in Rio, Manaus, and the northeast of Brazil.

Brian: Let me ask you a follow up question about the P.1 variant. I know the Wall Street Journal reported last week that a rise in deaths among younger Brazilians is fueling fears about that and possibly another variant. I'm curious if you think there are global implications from Brazil's failure to control the P.1 variant in your country.

Dr. Dalcolmo: Well, I'm not that fear that we are not controlling the P.1. First of all, because Brazil is locked, we cannot wait, all the frontiers are closed, so we have a very few number of flights, international flights to Brazil these days, but the variant is completely spread out in the country. The new one, the P.1 variant is responsible for more than 80% of the new cases in the country now. This is completely clear for us. Because it is much more transmissible, we are having more and more cases in younger people.

To give you an example, because our elder population is already vaccinated, so the very old people are vaccinated so far, but we are having cases of-- all the patients, for instance, to give you one private example, that I am taking care today are under 40 years old, 50, the one over 47, but the younger people. This variant is much more transmissible and the profile of the disease changed a lot.

We are having the pressure over the hospital system and occupied by much younger people. This is something that really worried us about. One thing that Natalia mentioned that I think it's very important for us to focus on Brian, is the question of the social inequality in Brazil. The situation of the new lockdown that we are having in big cities, like Sao Paolo, Rio de Janeiro, Recife, some of the big capitals of Brazil, with more than 1 million, 2 million inhabitants, each one, is the question of the social inequality. Because I don't know whether you are aware, but Brazil has 13 million people living in slums, so under the line of poverty.

For those people, it's very difficult for them to keep at home. It's difficult because they need to move. They need to go to search jobs or to search food. This discussion, that, for instance, the social help, the financial help that the emergencia help, how the government called, that the government provided during six months, stopped. Now, they started again, but one-third of the previous one. It's very low help, very little help. It's not enough.

Brian: Of course, we have that kind of socio-economic inequity with respect to the pandemic in this country, too, so you're describing something familiar. Dr. Dalcolmo, I thought we would wind up just taking phone calls from my country for you there in Rio, but we're getting a call from your country. We're going to go next to Angie in Brasilia. Angie, you're on WNYC, hello from New York.

Angie: Hi, Brian, thanks for having me on. I am an ex-pat teacher at the American school and I just wanted to talk to-- well, I just wanted to talk about the idea of diplomatic intervention. There are more embassies here in Brasilia than there are anywhere else in South America, and I haven't heard much. I know embassies are vaccinating their own, but I haven't heard anything about those embassies vaccinating the Brazilian population, sending in vaccines, aid, and then vaccinating those who support those communities. I don't know if anybody here who is on can speak to that, but it's something I haven't heard about at all, and I'm really interested in finding out more about.

Brian: Dr. Dalcolmo. Can you answer Angie's question?

Dr. Dalcolmo: Well, I couldn't, because I'm not aware of this, whether the foreign embassies. I know that they are vaccinating their own, but I don't know whether they are helping in this kind of thing. I don't know.

Brian: All right, then let me get one more in here, Maria, all right. We took an American living in Brazil, now we're going to take a Brazilian living in Manhattan. Maria, you're on WNYC with Dr. Dalcolmo. Hello?

Maria: Hello, guys. My name is Maria Lima. I am a Brazilian-born scientist who lived in the US for about 30 years, a microbiologist and immunologist. I know Fiocruz well, since I was trained in Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. My comment is somewhat linked to the comments of the last caller. We were talking about a week, a week and a half ago, that the United States going to have a glut of vaccines, we're going to have more doses of vaccinations than we probably can do something with, so why not, working through the diplomatic channels and sending some of those vaccines to Brazil, which obviously we don't have enough there.

We have all the variants that are coming up because they are a lot of people that are infected. This is compassionate, and it is also good public health to prevent the spread, even to the US.

Brian: Thank you so much, Maria. Dr. Dalcolmo, go ahead.

Dr. Dalcolmo: Good question. Very good comments she raised, because I was about to raise the same one, Maria, so thank you so much. It is necessary, Brian, now, because we have this changes. In Ministry of Health, we have a new one, the fourth actually, and we have a new chancellor of the country, foreign affairs minister. We hope that they can retake this diplomatic negotiation.

We know that countries like you US, Canada, they have more doses that it would be necessary to cover the population. For instance, the vaccine of AstraZeneca that you are not using in US, but it is regulatorily approved in Brazil, could be a good example, but this is something that I know, I am aware, so far that it is started, a negotiation, but we have to improve it. I fully agree with her comment

Brian: Before you go, I see that Brazil is having a separate political crisis on top of the peaking of the pandemic. As I understand it, after President Bolsonaro fired Brazil's defense minister, the heads of the country's army, navy, and air Force all resigned this week. On top of that, Bolsonaro replaced six different members of his cabinet. Now, for people in this country who are not following, I know you're a doctor and not a political journalist, but is there any implication to that political turmoil for the public health in the middle of the pandemic?

Dr. Dalcolmo: I don't think that it is directly related, but it does represent a internal crisis undoubtedly, Brian. The question would be located, I would say, between the minister of health, the new one, the politicians from the high chamber, and the Senate, of the low chamber, the deputies, the senators. They are having a good role at this moment, and they are making a pressure over the president.

This has been a good, I would say, kind of dialogue. They are calling us, they are listening to us, they are wanting to take and the Supreme Court as well. We are having a new, I would say profile, the momentum is interesting now, in this in this sense, but this change of minister of defense, particular the army, I don't think they would interfere directly in this question related to the public health. In addition, because they are the new ones, already made manifestations, public statements that they full agree with the public health measures that have been taken by the new minister.

Brian: At least there's that. My guest has been Margareth Dalcolmo, doctor, pulmonologist, professor, and clinical researcher for the Public Health National School of the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Fiocruz. Thank you so much for your time today. We really appreciate it. Good luck to you and everyone in your country.

Dr. Dalcolmo: Pleasure. Pleasure, Brian. Bye-bye.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.