The Cost of a Year Without Cancer Screenings

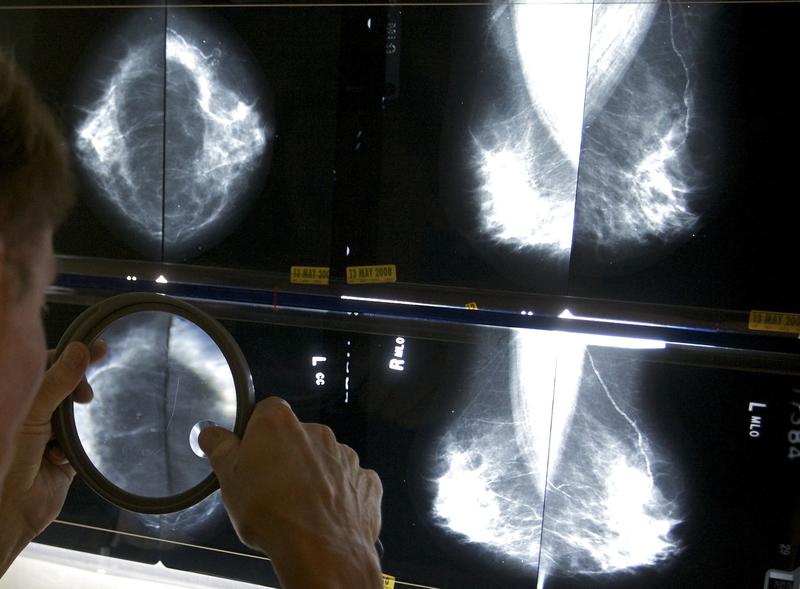

( Damian Dovarganes, File / AP Photo )

Brigid Bergin: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. I'm Brigid Bergin, a politics reporter in the WNYC in Gothamist newsroom, filling in for Brian, who's off today.

According to the current estimate for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, over 561,000 people have lost their lives to COVID-19 in the United States. Among the many things that the pandemic has disrupted, is diagnosing and treating cancer. In the next decade, we could see over 10,000 excess deaths from just breast and colorectal cancer alone according to the National Cancer Institute. That's because so many people couldn't get the screening they needed in order to catch these cancers earlier.

Joining me now to talk about her reporting and how avoiding health care settings during the worst of the pandemic has led to some cancers being found later when treatment options are more limited, is Duaa Eldeib, investigative reporter for ProPublica. She's joined by Dr. Pam Khosla, Chief Hematology/Oncology at Chicago's Mount Sinai Hospital, where she's a cancer committee chair and associate professor of internal medicine at the Rosalind Franklin University of health sciences.

Duaa and Dr. Khosla, welcome to WNYC.

Dr. Pam Khosla: Thanks for having me on.

Duaa Eldeib: Thank you.

Brigid Bergin: Duaa, you write, "Advances in prevention increased early detection, improved treatment, and new drugs fueled a 31% drop in cancer death rates from 1991 to 2018." How disruptive has COVID been? Has the medical community seen anything like this before?

Duaa Eldeib: This has been the most disruptive to cancer care and research that the United States has ever seen. Like you said, there's been steady progress over the past two decades, but when COVID hit, what it really did was risk all of that progress, risk the lives of so many people who weren't able to go in to continue treatment or to get screened or to go to their primary care doctor. It set back all of the research that was happening in a lot of different cases on cancer care and prevention and treatment.

Brigid Bergin: Duaa, you profiled the experience of a woman named Teresa in Chicago, who's been diagnosed with stage four inflammatory breast cancer. She's also one of Dr. Khosla's patients. Can you tell us more about Teresa, her symptoms, and why she delayed going to the hospital?

Duaa Eldeib: Teresa is a 48-year-old factory worker and mother. She spent almost half her life working at the same Chicago Candy Factory. She has three children whom she loves. This is a woman who sleeps in the living room because she wanted to give each of her children their own room. For her, her job was really a way to provide for her children, and that's why when the pandemic hit, many of us were able to work from home, she kept working at the factory. When her colleagues called in sick with COVID, she worked even more. She was afraid of losing her job, afraid of falling behind, again, on the mortgage, afraid of not being able to provide for her family, and she was also afraid of going to the doctor or the ER in the middle of the pandemic.

When she started to feel symptoms last year, she ignored them. Her right breast was swelling, so she stuffed the left side of her bra so no one would notice at work. She grew more tired, but she kept going to work until really the pain was unbearable. That's when she decided to schedule a telehealth visit. Unfortunately, during that visit, the doctor wasn't able to physically examine her. She told her that it looked like an infection. She prescribed her antibiotics. The antibiotics didn't work because obviously it was an infection. It wasn't until a few days later when she broke down crying that she went to the emergency room at Mount Sinai, and later she met with Dr. Khosla who diagnosed her with stage four inflammatory breast cancer.

Brigid Bergin: Dr. Khosla, when you saw Teresa after her initial visit to the ER, what was your first impression of her case?

Dr. Pam Khosla: I think whenever we see a very inflamed-looking breast and with the skin findings which even without you palpate think the breast, you can just look at it and tell this is a very aggressive inflammatory breast cancer. Her whole breast had been lifted up all the way almost to her collarbone. The right arm was swollen, that's called an orange peel or peau d’orange appearance. There was already a punch biopsy that I had the ER doctors call the surgeons and do it then and there in the emergency room, so I had results the same day. This case moved very quickly because we knew this woman had waited a long time before coming to seek appropriate medical evaluation.

Brigid Bergin: Listeners, we're wondering if anyone out there listening has had an experience with delaying cancer screening or seeking treatment due to COVID-19, whether yourself or a loved one. If you want to share your stories, call us, what decisions did you have to make? You can tweet @BrianLehrer, or you can call us now at 646-435-7280. That's 646-435-7280.

In Duaa's article, Dr. Khosla, you were quoted as saying, "If she would have come six months earlier, it could have just been surgery, chemo, and done. Now she's incurable." Can you talk about the importance of early detection? Six months isn't a lot of time. How much of a difference does that make when it comes to cancer treatment?

Dr. Pam Khosla: Right. Within most breast cancers, three to six months is not a big time frame where a cancer would go from being curable to incurable. Inflammatory breast cancer, which is what my patient had, is less common, less than 10% or so of patients, and goes very fast. It's one of the most aggressive breast cancers that we have in women. There's nothing subtle about its presentation. It's very distinct from a small lump that a woman feels, is not sure if that really is cancer or not, is it growing or not. Those have a long doubling life for a long time before they become clinically significant.

In inflammatory breast cancer, the moment there are changes of the skin overlying the breast, that's a red flag to see treatment right away. Unless a woman is in her postpartum period, or is lactating where mastitis and infections of the breast are more common in a younger woman, or a woman that's had surgery of some kind that she could have an infection, but in a woman who does not fit those criteria, she needs to seek immediate medical attention when there are changes in the nipple or the skin unrelated to any of the other preceding causes.

Brigid Bergin: You started a program at Mount Sinai in Chicago last year in order to encourage patients to come in for cancer treatments during COVID. What outreach did you do, and what did the patients really need to hear to come in?

Dr. Pam Khosla: Right. Our figures dropped for screening mammography by like 96%. I think across the country, many, many cancer centers in the spring of 2020 March and April had many of the screening programs shut down. We were prioritizing, taking care of the emergency room influx of COVID-19 patients.

Right after we opened up in May of 2020, late May, we started partnering with one of our organizations within the Sinai Health System, is the Sinai Urban Health Institute, which is very well known for its community health worker programs and outreach into the community. We also offer free mammograms through some grants and Illinois breast cancer and cervical cancer screening programs.

I think it was really reaching out into the community through community health workers and advocates, and making everyone aware that screening was up and running again. Especially, I think the group within cancer that took the biggest hit was lung cancer, which is relatively fast-growing. Patients were delaying these low dose ct scans, and there's enough data that's already come out showing patients that would normally have only 8% or so of lung cancer [unintelligible 00:10:00] being cancerous in the lungs now had about 30% of them. This came out of Cincinnati, but that's being felt across the board with breast cancer. Like I said, fortunately grows a little slowly. You do have room to postpone by three months, six months, or until it's felt safe. Again, normal screening had to resolve, and I don't think we've caught up all the backlog yet. We're still struggling with catching up all the backlog from last year.

Brigid Bergin: If you're just joining us, you're listening to The Brian Lehrer Show at WNYC. I'm Brigid Bergin from the WNYC in Gothamist newsroom. I'm speaking with Duaa Eldeib, investigative reporter for ProPublica, and Dr. Pam Khosla, Chief of Hematology/Oncology at Chicago's Mount Sinai Hospital.

Let's go to the phones at Dana in Queens. Welcome to WNYC.

Dana: Yes. Hi. I was diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma on one shoulder, and it was a small grouping of bumps, and they [unintelligible 00:11:15] shaved it off, apparently. There's no scar, but I was told I have to be followed up every six months, but that was a year and a half ago. You can see that I haven't been following it up. It was because of fear, and it seems to be like a habit, keeping away from all doctors now. I'm over 70, and it was started off as having a usefulness. Oh, it's still useless. I don't know how to get started again. You think the doctors want to see me or are they fearful themselves? I'm not sure.

Dr. Pam Khosla: I think that's an excellent question. One of the things is, for skin cancers, it's the physical exam is very important. If you could connect with your dermatologist or your surgeon again, and try to do a telehealth visit where some kind of pictures of the area may be at least feasible, but if you've had your vaccination, I would say it's probably time to go in and have that looked at. It's not just that area, but the other areas of the skin that needs to be under surveillance.

Brigid Bergin: Dana, thanks so much for calling. As with so many aspects of American life, the pandemic has exposed the racial disparity of cancer rates. Duaa, can you talk about what you found in your reporting?

Duaa Eldeib: Yes. Like you said, what we saw from the pandemic, is it exacerbated these racial disparities, and we saw the communities that were hit hardest were communities of color. Unfortunately, the same thing is expected when we look at the impact of delaying care because of the pandemic on cancer. A large part of that is because these groups were already vulnerable, to begin with. Black Americans die of all cancers combined at a higher rate than any other racial group. For Latinos, cancer is the leading cause of death. For women, specifically breast cancer is the leading cause of death for Latino women. All of this already made them vulnerable. Then when you talk about access to care, health insurance ability to seek treatment, all of that is exacerbated by the pandemic, and unfortunately is expected to lead to even worse outcomes.

Brigid Bergin: Duua, as much as your reporting looks at the impact of these delayed screenings, it's really also a story about the demands on essential workers, and people whose jobs are demanding and who are afraid of losing their jobs, as you described. Is that something that you've seen in other cases? You certainly saw it in Teresa's case.

Duua Eldeib: Yes, and it's something that I've heard from readers across the country. Once the story ran, there was a woman who emailed me and who said, basically she was almost Teresa. She started having symptoms, but she was not inclined to go in. She did not want to go in, but she had a flexible job. She had good insurance. She had a support network that really pushed her to go in. She was diagnosed with cancer almost one year ago, but she had been able to undergo treatment. With essential workers, with Teresa, her son kept encouraging her, "You should go into the doctor, mom, let me take you to the hospital". Her response was, "As soon as I get a day off of work. I'll go in as soon as I can get off of work," but she never had a day off of work to go in.

We have a similar-- I'm sorry, go ahead.

Brigid Bergin: No, go ahead, please.

Dr. Pam Khosla: I think we've learned about, any time there is a recession of an economic impact from a pandemic right now. Back in 2008, after the financial recession, there was internationally loss of jobs and insurance. We saw a surge in cancer stage at presentation due to delayed diagnosis. This was later accompanied by a transient increase in cancer mortality at that time back in 2009. Since then, cancer mortality has decreased by about 28% from 1999 to 2018, the latest figures, especially for lung cancer. New drug development has led to, and smoking cessation has led to about a 37% decrease in lung cancer mortality. I think, we as oncologist, are fearing a surge in mortality because of these delayed diagnosis. We will not find out, for years to come, the true impact of the financial burden that the pandemic created.

I was interviewing another colleague and myself, and they worked for Kaiser, and she informed me that Kaiser had done a full showing 49% of women lost jobs as compared to much less number for men during the pandemic. That resulted in about 11.5 million of women overall versus 9 million on a pure research as well. Then women also tend to skip medical and dental care in order to take care of family, especially if it's a single mother, as compared to 33% of men skipping medical or dental care last year. I think the worst on the statistics is still to come. Teresa was the beginning of that story in January. I have to say, I've personally feeling exhausted with the amount of delays that we're seeing now that have led to cancers that would easily curable. It just brings in everything that the pandemic has done upfront and bold in a very sad way.

Brigid Bergin: I can imagine how hard it must be to witness and to work in that, Dr. Khosla. I'm wondering, we've talked earlier in the show about COVID vaccines. People who are in treatment for cancer can have suppressed immune systems because of their treatments. What was it like as a healthcare provider in terms of keeping your patients safe, not only during their screening, but afterward during treatment?

Dr. Pam Khosla: Right. I think that's one of the calmness questions we're getting these days. Is it safe for me to get the vaccine? I have friends, family members across the board internationally asking the same question. So far, the recommendations from both CDC, NCI or ASCO, our parent organization for oncology American Society of Clinical Oncology, is that yes, all patients should be vaccinated, except if they've had a stem cell transplant and are on immunosuppressive therapies. Probably it would have to be delayed until they have immune reconstitution, but again, they need to talk to their oncologist that are some hematologic malignancies or blood cancers like myeloma CLL. Those patients may not have a robust immune response to the vaccine. Still doesn't seem like there's a downside to it.

Convincing patients, I have made it my personal agenda because I know CDC is currently looking at how to reach out to the patients that have been refusing, or even general public that has been refusing, just reach out through the providers. Because we have a relationship with the patient. Just met with a patient yesterday. She's a survivor. We have more survivors, by the way, now as compared to patients just in general in cancer.

She was like, "I'm really skeptical, my mom got the J&J vaccine, she is 80." The patient herself was about 65. She's like, "I'm skeptical, but if you say, I'll take it." I was like, "Okay, I have to tell every patient, ask this question. It's very much behooves on all of us to try to inspire and instruct and, tell our patients it's really more prevention than they could think of any other way.

Brigid Bergin: Let's talk to Dante from the lower east side. Dante, welcome to WNYC.

Dante: Hi, I'm calling because actually, my aunt passed away this summer. She had multiple myeloma for over 10 years. Due to the pandemic, it really interrupted her regular visits to the hospital, and I think for multiple months, she just wanted to go to the hospital and complicated her response, and led to her passing, in some way. I just want to fill in that side of the story as well for cancer patients during the pandemic and their access to care.

Brigid Bergin: Dante, thank you for calling and sharing your story. Go ahead, doctor.

Dr. Pam Khosla: Sorry about that. Yes, the moment you mentioned multiple myeloma, I have a patient of mine who survived breast cancer 10 years ago and then got diagnosed with multiple myeloma three years ago, and yes, felt the same. We had barely got her into complete remission and, during the pandemic, it was juggling between when we did reopen two months after a complete shutdown, which patients should come first. Luckily, my patient's doing well, but, I'm wondering if your aunt could get some oral treatments, pills for maintenance.

Brigid Bergin: Dante-- Go ahead, doctor. I think we don't have Dante anymore.

Dr. Pam Khosla: I think most oncologists do have some strategies to switch some of the drugs from IV to either self-administered at home or oral. Please do talk to your own doctors for directions. Patients shouldn't just sit and not try to engage with their healthcare team. Telehealth has been a great, great benefit during this time. In fact, sometimes I feel very nice seeing the family, the home, the surroundings, and seeing patients in their own comfortable surroundings rather than have to come in, especially when the weather was bad during the winter months.

Brigid Bergin: I just want to acknowledge, I think our caller, Dante, I think his aunt has already passed away, but your advice, Dr. Khosla, I think is useful for other folks who may be still trying to determine treatment options with the type of cancer that she passed away from.

Doctor, I wanted to just ask you one question related to, again, the COVID 19 vaccine. Other vaccinations can cause temporary enlargement of lymph nodes. Should women be waiting to get mammograms after their COVID shot? If so, how long?

Dr. Pam Khosla: I think the NCI actually came out with a statement about that because we started seeing a lot of consults in the last few months since the vaccine came out, referrals for two big reasons which jumped in the hem-onc world, which are related to the vaccine. One was the lymph node enlargement under the armpit, creating unnecessary alarm about lymphoma or breast cancer. Then the second has been more of blood than hematology related, thrombocytopenia, low platelets, bruising, and clots. Yes, the recommendation is to wait four to six weeks after completing COVID-19 vaccination before getting a mammogram so that it does not create unnecessary alert.

We always ask patients to have an exam done by their physician after doing the self-exam, if there is anything that they feel or are seeing any tenderness or pain under the armpit. Also on mammography, we can easily, and ultrasound, can easily distinguish between a malignant looking lymph node versus a benign-looking lymph node in many cases, but still, it does create a lot of anxiety, and sometimes unnecessary biopsies being done. Six weeks is a good time to wait. If it's still palpable or still felt under the armpit, first have your physician examine you and reconsider when good mammography be done in a better way.

Brigid Bergin: Okay. Duaa, Just as we get near the end of this segment, I know that some of the human costs will be due to the lack of screening and early detection, but COVID has also impacted by cancer research and delays there. Did you come across much of that in your reporting?

Duua Eldeib: I talked to a couple of oncologists who told me about grants that they had applied for, or in the pipeline, and then were told that they actually had to redistribute the money to COVID research. That was something that I heard a couple of times, and I read that as well, that when COVID came in, as we all know, it was this new deadly virus, and everyone was rushing to understand it, which is completely understandable, but the long-term effects of that is what was being researched at that time had to be put on hold, and the cancer world that delay has fatal effects, unfortunately.

Brigid Bergin: Just to clarify, Dr. Khosla, we got a caller with a question about a comment you made related to the time that someone could wait to do a checkup. I think the caller heard you say six months as a follow-up for a cancer screener. Did I hear that correctly?

Dr. Pam Khosla: I said somewhere between three to six months. Each case is different. Mammography is a better tool for an older the woman is, and has much more sensitivity in picking up abnormalities. A breast exam for a younger woman may be much more likely to pick up abnormalities. Tests like lung cancer screening with the low dose CT probably should not wait more than three to six months at the most. Cervical cancer, pap smears can wait if they've had one done within the last three years, the recommendation is every three years.

Colorectal cancer screening, if they cannot get to a colonoscopy, the fit test and the DNA test done at home are excellent alternatives. Every patient is different. If there's something that's being already watched on a screening exam that was abnormal the year before, that patient probably should not wait more than three months. These are very rough estimates, and there's no form guidelines at this time. It's more of stay in touch with your doctor. If you have a strong family history of cancer, or have a genetic mutation that's related to cancer risk, those patients definitely need to go within the shortest delays that they can afford to do. Your physicians will guide you through that process.

Brigid Bergin: Well, I want to thank you both for your reporting and for your hard work. We're going to have to leave it there today. My guests have been Duua Eldeib, investigative reporter for ProPublica, and Dr. Pam Khosla, Chief of Hematology/Oncology at Chicago's Mount Sinai Hospital, cancer committee chair at Mount Sinai Hospital, and associate professor of internal medicine at Rosalind Franklin University of health sciences. Thank you both so much for coming on today.

Dr. Pam Khosla: Thank you.

Duua Eldeib: Thank you.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.