The Climate Emergency

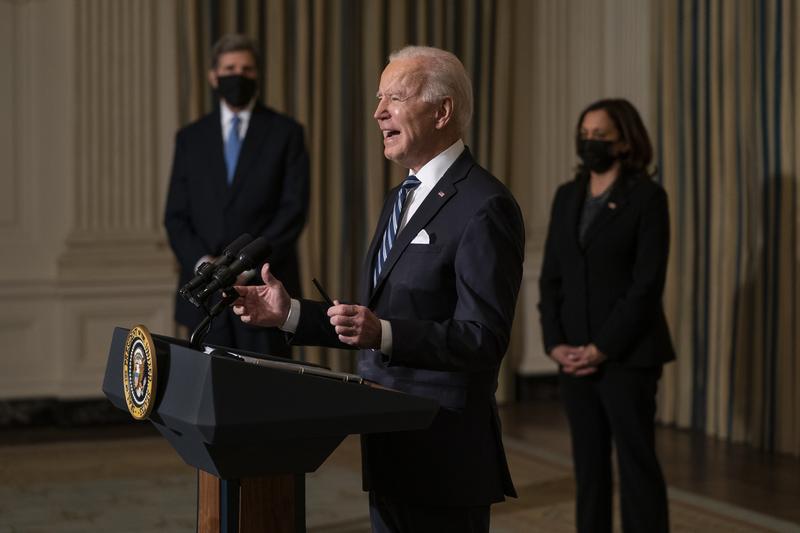

( Evan Vucci / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. Coming up this morning, Susan Page, the USA Today Washington Bureau Chief who has a brand new book called Madam Speaker: Nancy Pelosi and the Lessons of Power. One review of it says it's kind of the big historical figure biography that's usually written about men. We'll also talk to Susan about what's happening under Pelosi's leadership right now, including the George Floyd Justice and Policing Act and other things that can pass the House pretty easily, but probably not the 50/50 senate, how Pelosi is trying to navigate past that dead-end. That's coming up.

Also, with Cy Vance retiring from his job, will assess the race for Manhattan DA. Some interesting endorsements in that race. Preet Bharara endorsed one person, other prominent politicians have endorsed another and on from there, and DA Vance's announcement yesterday that he will stop prosecuting sex workers, a big legacy move from Vance, who I think really wants to be remembered as a progressive prosecutor, not for some of what are sometimes seen as his missteps earlier on with Harvey Weinstein and the Trump Organization. That's coming up, but here's where we begin.

Today is Earth Day. Happy Earth Day, everybody. We are fortunate to have with us right now, three leading scientists and communicators about science. In the media, we all say follow the science. Then most of the time we talk to politicians. This should be a treat, as well as maybe even legit. It comes on a morning when President Biden is holding a virtual climate summit with world leaders and just committed to the most aggressive US climate goals yet to cut greenhouse gas emissions in half by the year 2030. Now my calculator app tells me that's just nine years from now. Some things are going to have to change fast, but the President didn't say what, maybe our guests can give us a clue.

With me now, Laura Helmuth, Editor-In-Chief of Scientific American. She was previously the science and health editor for The Washington Post and president of the National Association of science writers. Sir David King, a chemist who has held many prominent positions including Chief Scientific Adviser to the government of the UK, Special Representative for Climate Change to the UK Foreign Secretary like our Secretary of State, chair of the Physical Chemistry Department at Cambridge, and much more. David was knighted for his accomplishments back in 2003.

Dr. Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, professor of soil biogeochemistry, at the University of California at Merced. She specializes in research on how soil helps regulate the climate, and how the effects of the warming climate like more severe wildfires and droughts and an earlier spring affect soil and the food produced for people who depend on it. She was also a member of former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan's millennial ecosystem assessment in 2005, which forecast rising poverty in parts of the world based on degradation of ecosystems because of warming. Last year, she won the Carnegie Corporations Great Immigrants Award. So Laura Helmuth, Sir David King, and Dr. Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, welcome all of you to WNYC.

Sir David King: Thank you.

Laura Helmuth: Thank you. Happy Earth Day.

Asmeret Asefaw Berhe: Thank you.

Brian: Listeners, later in the segment, we will open up the phones for your climate science questions, hold them for the moment. Laura, as editor of Scientific American, I see you in a group of news organizations under the umbrella of covering climate now that has decided to begin using the term climate emergency rather than climate crisis, which you had been using. What's the difference between a climate emergency and a climate crisis that made you decide that's the proper journalistic term?

Laura: Yes, thanks for asking. Also, WNYC is a partner in the Covering Climate Now consortium. There are about 400 media organizations that are sharing our stories about climate change. A lot of us have decided that climate change was a fine word for a while, there were political reasons to call it that. Climate crisis is also accurate, but really we need to start saying climate emergency because it's emergency right now. We can't just wait and think about it and debate anymore. The longer we wait, the worse the emergency is, and basically emergency means we must act on it.

Brian: Well, in your article on this, you likened it to an individual who was chest is pounding and lips are turning blue as they stumble on the sidewalk, but many people think of climate change as a more gradual threat to the planet and humanity, rather than something so acute as that medical emergency on the street analogy? Can you give a scientific example or two of the conditions that led you to adopt the word emergency?

Laura: Yes. Last year, of course, we were all focused on that COVID pandemic, but just last year, we ran out of names for hurricanes, there were record-setting wildfires in California and Australia, Siberia hit 100 degrees Fahrenheit for the first time, there were floods and landslides all over South Asia that displaced more than 12 million people, so it's an emergency. Terrible things are happening already and it's just going to get worse and get worse quickly.

Brian: Now, Sir David, by earlier this month, I see more than 13,000 scientists had signed a report warning of a climate emergency using that word, as a statement of science, not politics, as Scientific American describes their choice as a scientific choice, not a political one. Are you a signatory to that letter as a chemist? Scientifically speaking, how would you make that distinction between crisis and emergency?

Sir David: Right, not only am I a signatory but well before that in 2017, working within the British government, the British government said, "We are now describing this as a climate emergency." Let me very quickly try to answer your question, Brian. In the Arctic Circle region, we have things happening that are already but will impact on the whole world. The Arctic Circle region is heating up at about three times the rate of the rest of the planet, and the reason is very simple. The Arctic ice covering the Arctic sea has been disappearing much more rapidly than the climate science community predicted.

Today, during the Arctic polar summer, the sea is exposed to the extent about 50%, 60% of the total sea is exposed to sunlight. The sunlight is absorbed by the blue sea very efficiently, and the sunlight was efficiently reflected by the white ice before that, and that is the reason it's heating up so rapidly. Sitting in that blue sea during the polar summer is, of course, Greenland. When all the ice has melted on Greenland, and it's already beginning to melt more rapidly than was predicted, we know that global sea levels will have risen by about 7.5 meters, about 24 feet. What we can anticipate is actually in the near future.

We're looking at, for example, Jakarta, which was underwater, for much of January, February this year. We're looking at the whole of the Southeast Asia region, which is most impacted by rising sea levels, partly for the reason that Laura has just said because we're seeing much more intense hurricanes than before because hurricanes pick up their energy from the ocean itself, and the oceans are getting warmer, and so there's more energy to be taken up into the hurricanes. That means, that in Southeast Asia, in just 30 year's time, we're predicting that something like 90% of the landmass of Vietnam, the whole country will be underwater once a year, at least.

Jakarta will be fully flooded by then and the government of Indonesia, we've been advising them, have already decided to move the capital to other ground. That's an enormous city, 13 million-plus people. It's a bustling modern city that has really been built up in the last 20, 25 years, because of the rapid growth in the economy in that region.

If I then take you to Kolkata, that is not going to be viable for much longer. If we go over the water to Bangladesh, again, the place where massive flooding will have occurred. We're looking at a region of the world where unless rapid action is taken, we're going to see something like 200 to 300 million refugees. Let's say 200 million refugees by 2050, in just 30 year's time. I think when we describe an emergency, we're saying really, whatever we do about climate change over the next five years, may well determine the future of humanity for the next millennium.

Brian: Sir David, thank you for those very concrete examples. Listeners, on his last one if you're interested in more on climate refugees, that was our Earth week topic yesterday on this show, I refer you back to our file on that if you want to listen at some point. Dr. Berhe as a biogeochemist, I guess you have to know Biology, Geology, and Chemistry. I would definitely have flunked out of school if I had to be proficient in all three of those fields. Do you see climate emergency conditions now in anything you study with respect to soil? If so, could you give us a concrete example or two?

Dr. Berhe: I agree with the declaration to call the climate change crisis an emergency at this point. I think the analogy to health emergency that you made earlier is appropriate one in this case because we're reaching critical points for the health of natural ecosystems. We've already started seeing significant effects to the health of the natural ecosystems, as well as the human communities around the world that depend on those natural ecosystems.

I think first and foremost, I think it's really important that we use the right words, words matter. I assume you appreciate that as a public speaker and a newsperson. I think from the perspective of soil, it's a pivotal moment. I think it's a really important moment that we actually start to address this issue as the significant effect issue that it is because many, many communities around the world, we're talking about hundreds of millions of people around the world, who their lives are getting upended by the climate crisis that is compounding, and already existing land degradation, food, and nutritional insecurity problems.

By this, I'm referring to the issue of how climate change has now become what we call a threat multiplier. It is making the already difficult problems with climate and soil health and that are needed to support plant productivity and food production around the world very, very difficult. When it comes to the soil, just as you ask, just in the last 200 years or so ago, because of how we've been using and abusing soil and the added pressure of climate, we have lost about 120 billion metric tons of carbon that was in soil to the atmosphere.

Meaning the climate change has caused so much carbon that was in soil to be released into the atmosphere making the climate crisis even worse. We need to get this problem in check and we need to act in a decisive manner right now so that we don't make our climate predicament even worse. I think that's important for the livelihood of people that depend on the soil and all the natural living things that depend on the natural environment for their livelihood.

Brian: Here in the middle of New York City or anywhere our listeners are in this great metropolitan area, soil is not usually the first thing they think about, but one of the reasons your work seems so interesting to me is that you seem to be documenting, and I think you were just getting at this a scientific feedback loop if I can call it that in which, for example, the effects of warming cause drought, and then the drought affects the amount of carbon in the soil, which feeds back to the climate, which then causes more drought. Is that a decent and fairly accurate example?

Dr. Berhe: That's a pretty accurate, very accurate example. We call this a positive feedback loop where warming is causing fast rate of decomposition and loss of carbon that had been stored in soil over hundreds of thousands and longer years. When that carbon is no longer in soil and it's released into the atmosphere, it causes even further warming causing even further impact to the soil and causing it to lose the carbon, but the impact doesn't even stop there because soil that lose this large amount of carbon is also soil that no longer can sufficiently support plant productivity. It cannot sufficiently provide all the resources that living communities on land need to survive and thrive.

As a result, this problem just keeps getting worse and worse when soil is impacted in this manner. If you will allow me, I think it's important to mention that the reason why soil is so important in this context is because soil stores roughly about 3,000 billion metric tons of carbon. For comparison, that's twice more than the carbon that's in all of the world's vegetation, plus all the carbon that's in the atmosphere combined. Any small change in the amount of carbon stored in soil and released to the atmosphere makes a huge difference in the warming of the earth atmosphere.

Brian: Listeners, your climate science questions now welcome here for our all-star earth day panel of scientists and science communicators at 646-435-7280, 646-435-7280. Or you can tweet a question @BrianLehrer. If you're just joining us. Guests are Laura Helmuth Editor-in-Chief of Scientific American, Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, professor of soil Biogeochemistry at the University of California at Merced, and Sir David King Chemist and former Chief Science Advisor to the government of the UK.

646-435-7280, Laura in Scientific American's article about the thousands of scientists signing that emergency declaration, it says the adverse effects of climate change are much more severe than expected. Yet I'm sure all our listeners feel like they've been hearing people sound the alarm bells for 20 years or more. It was already expected to be bad. Could you give us an example or two from the science of how the increase in severity is outpacing what we might've expected maybe when Al Gore's movie on this came out?

Laura: It's true. That's one of the great challenges for journalists who are covering climate, which frankly, all journalists should be covering climate because it's the most important story of our time. [unintelligible 00:16:42] you get to understand that this is a serious problem and it just keeps getting worse. It's a little bit mind-boggling. I think the scientists who've been issuing the international reports every few years on what are the projections for climate change, there's always a range because there are so many different factors that go into it, especially human behavior.

Unfortunately, every time there's a new report, the worst-case scenario is what has come true from the last time. As bad as the predictions are, we seem to always do even worse than some of the worst predictions, which can be disheartening. It's really important to have this dual message of, "Climate change is getting worse a lot faster than we even predicted last time we warned you about it, but there's still time to act, and now is the time to act." That's our challenge. It's a complicated message.

Brian: Dr. Berhe, let me bring you in on this pace of change question because I wonder if you have any observations that relate back to your work on the UN's 2005 millennial ecosystem assessment report, which forecasts rising poverty in parts of the world, based on degradation of ecosystems because of warming. Is there anything specific from that forecast of 16 years ago that you recall that you could comment on in terms of what's actually happened compared to what you forecast?

Dr. Berhe: I think the millennium ecosystem assessment, which was at the time, one of the very few ever approaches like that, that were taken to take stock of the health of the ecosystem, documented the rapid pace, which we were degrading the environment as well as changing the environment, including climate. As you can imagine, 16, 17 years in a field like this is a lot of time, but even then it was pretty clear that the pace at which things were going is very dangerous and that the rate of change is accelerating.

I think a lot of the things that we feared then, and that we described in that study at the time has come true when it comes to deforestation if you will, soil degradation, increasing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, and the role that humans are playing in facilitating a lot of these rather rapid and drastic change in environmental conditions. I just agree with what was said before about the pace of change is a really important thing to remember.

Yes, a lot of people like to talk about how the earth system also used to be warm at a different time in Earth's history, but I think it's really important to remember that the pace at which the warming is happening right now is rather unprecedented and if we continue on this pace right now, where we're heading is very dangerous territory in terms of atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide.

We could potentially reach unless we do something big to reduce emissions implements climate smart system management practices to take out the carbon dioxide that's in the atmosphere right now, unless we do both of these things, we can end up in atmospheric conditions that the world hadn't seen in the last 20, 30 million years. The worst-case scenario projections is that if we continue on businesses usual, we can even end up in situations where the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere that the world hadn't seen in the last 100 million years of Earth's history. I don't think any of us would be comfortable living in that kind of situation and it's quite important that we decisively act right now.

Brian: For people who say, "It's just a natural cycle, wait another 100 million years and will go back again," no, not quite. Okay. Before we take some climate science questions from our listeners, Sir David, you have straddled the scientific, academic, and political worlds I see, as chemistry department chair at Cambridge, a University President in Italy, chief science adviser to the government of the UK, how do you approach the role of science communicator to non-scientists politicians, who have to be convinced to make the best decisions based on science, which might not be the decisions most in their political interest?

Sir David: I have a very simple mantra, Brian, which is openness, honesty, transparency. Having that position, for example, when I became Chief Scientific adviser to Tony Blair, I said, "That is my mantra and sometimes you may be uncomfortable with it, but whatever advice I give to you, I am going to put into the public domain. In that way, I can maintain the trust of the public and I will manage to maintain your trust as well."

Now that is quite a big challenge to make. Brian, while I'm talking, let me say, what is currently happening is we have been used to talking about carbon dioxide emissions and carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere, but over the last 10 years, we've seen more than 10 years now, the rise of methane in the atmosphere is faster than that of carbon dioxide and methane emissions are rising for various reasons.

There's fugitive methane from oil, gas, and coal recovery, but also from farming. Because of the rapid growth of the global middle class, particularly in the new emerging economies of the world in Southeast Asia, China, India, and Africa, we're seeing farming producing much more livestock, which is a big methane producer, and much more rice, which is a big methane producer.

Then, we've already heard from Asmeret, about the emissions arising from land where it's heated. If you add methane today to carbon dioxide, carbon dioxide is at about 415 parts per million, but add methane as a steady-state value which you should do, you come to well over 500 parts per million. I don't think there's a climate scientist to believe we wouldn't be in dangerous territory if we exceeded 450 parts per million carbon dioxide equivalent. We are already in a position where there's too much in the way of greenhouse gases up there.

While I welcome very strongly, Biden's announcement of the United States reducing its emissions by 50% by 2030, let me quickly say, our Prime Minister, the British Prime Minister has announced today we will reduce our emissions by 78% by 2035. We've already reduced our emissions by more than 50% and we've effectively phased coal burning out of the United Kingdom, we began that industrial revolution, all backed off on coal mining, that is now finished.

I think we're saying the rest of the world needs to catch up and reduce emissions deeply and rapidly, but the next thing is we need to remove greenhouse gases at scale, and by that I mean 40 billion tonnes a year plus every year through to the end of the century, to reduce greenhouse gas levels to a level that is manageable for our ecosystems and manageable for humanity.

Brian: I hear your UK pride there in your country's accomplishments. Let me ask you one quick follow up question because if I have your bio right, you were chief science adviser, both to the Labour Party government under Tony Blair and a Conservative party government under Gordon Brown, how different were those experiences given who drives the different political interests of the two parties?

Sir David: Okay, so I have served under four prime ministers. A slight correction there. Gordon Brown was the Labour Prime Minister, followed by David Cameron. I served--

Brian: I was mixing them up with David Cameron. Go ahead.

Sir David: Right, I've served under David Cameron and Theresa May and my last boss in the foreign office was Boris Johnson. I have worked with all these different parties and I think it's perfectly feasible. The point is that if you're giving science advice, you're not giving it with some political bias and I think each of those Prime Ministers has understood this. Yes, I'm proud of what Britain delivered. I was I suppose instrumental in delivering all of that because that was my job, but what I'm not proud about is that greenhouse gas emissions are rising around the whole world.

I came into government with the intention of trying to manage the climate change problem, but we have got a very long way to go. I'm delighted that for the first time since 1992, we now have the United States taking a leadership position on real action. I say that with some emphasis because we haven't been helped by the US until now. More importantly in a way, we have China also massively committed to action. I think there's a partnership potential between China and the United States that could lead the world into proper action and this is the first time I can say with some emphasis, that this is the most positive development that has emerged recently.

Brian: You say that since 1992 has the US played this leadership role, you mean, not under Clinton, not under Obama?

Sir David: Well, under Obama, there was a moment when the United States played a leadership role and that moment was critical in getting the Paris Agreement through in 2015. No, I couldn't say that President Obama, much as I admired him, I couldn't say that he was focused on climate change in his first four years. I certainly think that he was rather hampered in his actions by the position of his Congress and Senate on climate change going forward. No, we have not been led by the United States prior to this and I'm just going to say, again, the two biggest emitters in the world are China and the United States and we now have both of them in a good place on this issue, and I hope the whole world will now follow suit.

Brian: A stat that I've cited here many times good for Americans to keep in mind for a little perspective, we have about 4% of the world's population. Based on various estimates, we admit 15% to 25% of the greenhouse gases. 4% of the world's population, but doing 15% or more of that pollution. We will continue in a minute and start to take your phone calls, listeners, with your climate science questions for our all-star Earth Day panel of scientists and science communicators. Stay with us.

[music]

President Joe Biden: The signs are unmistakable. The science is undeniable. But the cost of inaction keeps mounting. The United States isn't waiting. We are resolving to take action.

Brian: President Biden just a short time ago at his virtual summit of world leaders on climate change on this Earth Day and we continue now with our Earth Day all-star panel of scientists and science communicators. Laura Helmuth, Editor-In-Chief of Scientific American, Asmeret Asefaw Berhe a professor of soil biogeochemistry, at the University of California at Merced, and Sir David King, chemist and former chief science adviser to the government of the UK. Let's take a phone call, someone, calling anonymously from New Jersey, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Speaker: Yes. What my comment is that the branding of this whole concept is the problem. It was global warming, which in itself is very benign, and it doesn't alarm anyone and then it went to climate change, which is 10 times more benign. Any company that spends millions of dollars branding their name to get a good name, and nobody is alarmed by global warming sufficiently, and they're 10 times less alarmed by climate change. Where did this verbiage come from I don't get it?

Brian: Thank you. Laura Helmuth, editor of Scientific American, let me go to you on this and for people who weren't listening since the beginning of the segment, one of the premises here is that you and a number of other news organizations have decided to move to the term climate emergency. Yes, what was global warming, which sounded benign, and climate change, which doesn't even tell you the direction that it's changing in?

Laura: That's a good point, and I agree. I think a lot of times scientists and journalists try to use words that are as neutral as possible, and in that way, we end up not really almost obscuring the truth. You see this in journalism all the time, where we call something racially tinged, instead of saying it's racism. [inaudible 00:30:43] said instead of saying somebody just lied.

I think it's overly cautious way of using language that has not been serving the purpose of helping people understand what's happening in the world. Yes, that's why now just in the past few years, and I think especially this year. I think the COVID crisis helped us understand the importance of calling an emergency an emergency and making it really clear that we're not being alarmist, we're not trying to play this softer or quietly or show both sides, but we've got to say what we know, and what we know is that it is an emergency.

Brian: Alan in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Alan.

Alan: Good morning, Brian. Thanks for keeping up the great work. I've got a few questions about public understanding or misunderstanding of basic science that gets in the way of progress. Two of them have to do with maps, and one of them has to do with middle school science. The Mercator map exaggerates the size of the north and south polar regions, to most people who look at maps.

Brian: The Mercator map is the kind of standard flat map of the world that people might see?

Alan: Right, that has all the longitude lines going parallel instead of converging at the top. I think roughly one-third of the visible area in the polar regions is actually extent compared to the amount of BCI on a Mercator map. So we think there's more ice on the north and south poles than there really is and exaggerates our reserve.

The same problem arises because the actual converging longitude lines actually reflect the way heat concentrates like a funnel as they're generated along latitude lines, and they will rise in the same direction, converge to each other toward the pole. So you'll get polar regions receiving part of the contribution of heat from each unit being warmed up, and many other parts below it. That's why you have not just the effect after warming of blue water, where they used to be white ice reflecting sunlight up the North Pole, but that started with the problem of too much heat concentrating like a funnel as it rises toward the north and south poles.

Thirdly, people don't get enough of a reminder of the middle school science. Ice will absorb 80 calories per gram as it melts, only one calorie per gram as it rises one degree as ice or water. At the moment of melting, it's sucking up a vast amount of heat from the air and water around it, and we've lost massive amounts many, many cubic miles of ice over the last several decades.

Every one of those cubic centimeters of ice has absorbed heat from the surrounding area as it melts. Warming causes it to melt, but when it melts, it's momentarily cooling things. It's like leaving your refrigerator door open and being surprised to see that your kitchen might be a little cool as all the ice melts onto the floor, but that's a one-time event. When that ice is gone, you don't have any more cooling effects. People are getting fooled by a momentary cooling from this momentary melting, and they expect that's going to continue. That's why the Jim Inhofe snowball was such a deception. People need better science education.

Brian: Anti-climate scientist Senator Jim Inhofe from Oklahoma. Alan, thank you for all that. You're a good science communicator yourself, and since that was a contribution more than a question, we're going to go right on to the next caller. It's Yuvashree in the Bronx. Yuvashree, you're on WNYC. Thank you so much for calling in.

Yuvashree: Thanks, Brian, so much. Longtime listener, and what a great panel today. I wanted the panel to comment on, I'm going to say four major contributions or impacts from agriculture into climate change. The first one is just to talk about the role of carbon-nitrogen cycling. We have a fixed amount of carbon and nitrogen in the world. In the air, it's the carbon, it's a greenhouse gas problem. In the ground, it is changed into nutrients and one of the challenges today is the reduced nutrient uptake into plants that is due to a decrease in soil fertility largely related to climate change. We'd love to hear a little bit about that from the panelists.

Also, the role of well-managed grazing, not all livestock production is created equal. The role of well-managed grazing in building soil organic matter is actually crucial and critical in our agricultural system. I would love to hear some comments on that.

The third is the role of fossil fuels in agriculture. The amount of, for example, nitrogen fertilizers, which are I believe 250 times the equivalent to carbon dioxide. So methane is about five carbon dioxide equivalence, but nitrogen and nitrogen oxides are 200 plus times. Looking again at our agricultural systems and noting that if you go regenerative or organic, you do not use these synthetic nitrogen fertilizers, which are a huge contribution as well.

Finally, just talking about the solutions we're seeing today, especially in the US, and the role of carbon markets as being a sole indicator of how the soil interacts with climate. We know many of us who've been working in this for a while that carbon is just a single metric, and it is not representative of the actual soil fertility and soil health that you need for optimal carbon drawdown, but also cycling that carbon and nitrogen back into nutrients.

Brian: Yuvashree, thank you so much for all of that. I will say that to answer all those questions, it would probably take a two-week conference. Not one answer on the show, but so much information just in your questions. Let me throw that whole ball of wax to you, Dr. Berhe as a soil scientist. You want to pick up on any one thing in there and give us a little on it?

Dr. Berhe: Yes. I think that was a wonderful comment and questions. She's right. The carbon when it's just too much of it in the atmosphere, as well as CO2, methane, as well as nitrous oxide that could be released into the atmosphere, they're greenhouse gases and they contribute to warming, but when carbon and nitrogen actually is stored in soil, it serves as a really important reserve for food, energy, and nutrients for plants and microbes that call the soil home.

It's really important to think about this, but keep in mind that the biogeochemical cycles of carbon and nitrogen are continuously going, so some carbon is continuously being taken up from the atmosphere by plants during photosynthesis. When they die, or the animals that consumed the plants die, that carbon and the nutrients that the plants picked up from soil, enters the soil environment, and then it there it's cycled by activity of microbes.

That decay or cycling of the residue by activity of microbes is important because, one, it's a way that it acts that our waste is getting recycled, but at the same time, the nutrients that were trapped in the residue can also be made available for the next generation of living things that live in soil. These are intricately linked processes that are really important for health and functioning of the soil ecosystem.

The caller is correct in saying that carbon is just one metric, soil health overall is more like human health. Say if we go to the doctor, the doctor could use our blood pressure or some other health metric to speak about our overall health and how whether it's doing well or declining, but that one metric is just an index. Health is a little bit more complex than that one metric.

By the same virtue, the same thing applies for carbon in soil, but I think what the caller was getting at that's really important is also to remember that there are a number of regenerative agricultural climate-smart land management practices that would allow us to, first of all, just stop or decrease significantly the amount of carbon that is now being released from the soil to the atmosphere because of how we use land. Keep in mind that something like 15% of the greenhouse gases that are released into the atmosphere right now because of human activities come from how we use land.

From deforestation, from excessive tillage, and from how we use excessive amount of agricultural chemicals in agriculture and in the overall conventional agricultural system. If we can manage land better, including in grazing systems that she mentioned, but also in forestry as well as cultivated croplands, then we have a potential to, first of all, slow down that release and also take out additional carbon from the atmosphere and store it in soil, in pools that cycle very slowly. That is a critical component in my opinion of any effective climate change and mitigation strategy that we have to attempt right now.

Brian: Dr. Berhe is this all an argument for veganism to put it in individual behavior choices terms or not necessarily?

Dr. Berhe: Not necessarily. I think that this is more of an argument for being very careful in terms of how we manage land. Of course, reducing our consumption of red meat, in particular, and meat, in general, is an important part of raising land management that is sustainable when it comes to the health of the ecosystem. That's an integral part of it, but I won't necessarily come here and tell everybody that they should go vegan. That's a complicated decision for many reasons.

I'll just say that I think it's really important to realize that these natural climate change solutions that the caller was discussing are really important and they have also been proven to be effective to upset about a third of all the global emissions of CO2 we are now releasing to the atmosphere and can also do it in a cost-effective manner. Once we achieve these goals or even get partway in achieving the goals with climate-smart land management, we get way more benefits than just addressing climate change. We get a much healthier soil ecosystem that can support the needs of the growing human population and the needs of all living things on land.

Brian: Let me wrap up this segment by moving to the news of this morning and getting a final comment from Laura Helmuth since you're the journalist in the room as Editor-In-Chief of Scientific American, to comment on president Biden. This clip from the opening address of the virtual climate summit with other world leaders this morning, after he listed some of the items in his job bill that would cut carbon emissions and argue for those investments

President Biden: By maintaining those investments and putting these people to work, the United States sets out on the road to cut greenhouse gases in half by the end of this decade. That's where we're headed as a nation. That's what we can do if we take action to build an economy that's not only more prosperous, but healthier, fair, and cleaner for the entire planet.

Brian: What are the implications for the United States of that announcement of the goal to cut carbon emissions in half in this country by 2030?

Laura: It's very exciting to hear this and historically the way real change happens is through big policy changes. Going vegan, that's something that some people can do, but what really matters is policy. If we look back to the original earth day at that point, that was when we were getting the [inaudible 00:43:12] Act, the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act. Those policies have had a huge impact on our quality of life and on the health of the environment. I hope that this announcement today, in the future we'll look back and say, "It's another one of those really important changes that made the world a better place."

Brian: There was so much more that we could talk about obviously, but so ends our Earth Day all-star panel of scientists and science communicators for this Earth Day 2021. Laura Helmuth, Editor-In-Chief of Scientific American, Dr. Asmeret Asefaw Berhe, professor of soil biogeochemistry at the University of California at Merced, and Sir David King chemist and former chief science advisor to the government of the UK. Thank you all so much and happy earth day.

Sir David: Thank you, Brian.

Dr. Berhe: Happy Earth Day. Thank you all.

Laura: Thanks so much. Thanks for your coverage.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.