Climate Change Stories from Around the World

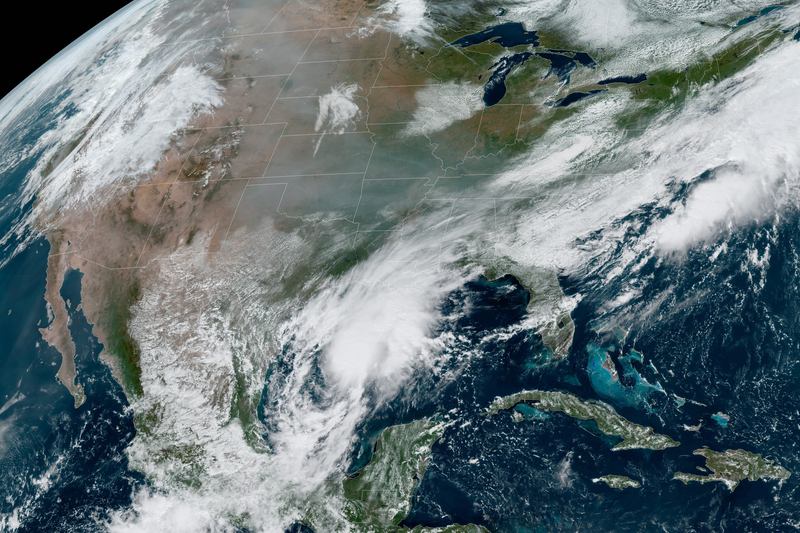

( NOAA via AP )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. Right now on The Brian Lehrer Show, we're going to take a trip around the world, except we won't be sightseeing in the usual way. No espresso or Chianti in Italy, no hikes up Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania, no Aurora Borealis in Sweden. Instead, we're going on an end-of-the-year world tour of 2021 in extreme weather events. You know the ones in this country, destructive fires in California, hurricane Ida battering Louisiana, and then flooding New York City businesses and apartments, and the tornadoes last weekend in the Midwest where the death toll has now hit 90.

There have been droughts, the hottest month on record in history globally, July 2021. Oh, yes, it's going to be 60° in New York City again today in mid-December, but what's going on in Lithuania? How about Qatar? How about Freetown, Sierra Leone? Interesting story from there that we'll get to because The New York Times opinion page has a sweeping new project called Postcards From a World on Fire, in which they compiled stories on the different ways climate change is affecting all 193 countries in the United Nations.

As it feels like we as a country in the world might be trying, but also spinning our wheels on real policy to address climate change, the harrowing project ends with a message from The New York Times editorial board, "Open your eyes, we have failed, the climate crisis is now." Joining us now is Meeta Agrawal, she led the project as a Special Projects Editor for New York Times Opinion. Meeta, welcome to WNYC. Thank you for coming on.

Meeta Agrawal: Brian, thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start by just diving around the world a little bit before we talk about the big picture. Tanzania, what happened there recently?

Meeta Agrawal: There were massive wildfires in Tanzania last October. One of the things that we tried to do as you said, is really look at the extreme weather events that were happening, not just in our backyard, but around the world. Fires, flooding, we got it all.

Brian Lehrer: Let's go to Freetown, Sierra Leone, which I mentioned a minute ago. I see that they just appointed their first-ever chief heat officer, or the first-ever chief heat officer in all of Africa. I don't know if any country has ever had one before. Tell us about that.

Meeta Agrawal: That's right. In Sierra Leone, they just announced in October that Eugenia Kargbo would be their first chief heat officer, and effectively, her job is to get Freetown ready for what they know will be a hotter, drier future, and to be really focused on the policies that they need to instate, and how they should get ready for that.

Brian Lehrer: Now, listeners, we're going to open the phones and our Twitter feed, and invite you to help us report the story. Help The New York Times opinion page for that matter, report this story indirectly, and add to this climate change around the world reporting project, this end-of-year world tour. It's 212-433-WNYC, 433-9692. How? Well, call in and tell us how climate change is affecting your country of origin if you're an immigrant, or maybe a place outside the US that you have any connection to if you're even not from there. 212-433-WNYC.

We are so US-centric in reporting in this country. We try to do these on this show from time to time, callers from anywhere, originally from anywhere, or with connections to anywhere, call in and talk about this, or call in and talk about that. Well, today, it's how climate change is affecting your country of origin, or any country outside the United States that you have connections to. 212-433-WNYC, 433-9692, as we talk with Meeta Agrawal, Special Projects Editor for New York Times Opinion, who led their new project out this week, called Postcards From a World on Fire.

I want to play a clip that actually comes with your piece, and listeners, I'll say this is not just text as you might think of a newspaper editorial. This is a lot of video. It's a lot of sound. It's amazing when you see it on their app or New York Times website. Let's listen to an audio clip. This is a birder from the Lithuania postcard, and for you birders out there in our area, this sort of story might sound familiar.

Birder: Each day I hear birds. I hear them in the sky. I hear them flying. I hear them migrating. They make this world much richer. I remember quite well, 10 years ago, the first time I saw wintering starlings in Lithuania, there were several birds singing, singing in January. I thought it is just an accident, but next year, again, more starlings started to spend winters in Lithuania. Just in several years, it has become normal, something is going really, really wrong. Of course, there are species who don't like those changes, like willow grouse, those birds were almost totally white. Last several winters were really warm, we had almost no snow, so it has no camouflage in winter, and the predators can catch them quite easily. So, it's gone.

Brian Lehrer: Meeta, enter this where you want, talk about Lithuania, or maybe talk about birds.

Meeta Agrawal: Sure. I think that what we were trying to do with [unintelligible 00:06:10] story is get at people's personal experiences of climate change. Sometimes I think climate change can really just seem like this existential threat, this invisible force that's out there that you know you should be worried about. What we really wanted to do is pin it down for people and show them how climate change has already changed the world around us.

It's changed every aspect of your life. It's changed how we live, it's changed how we work, it changed our leisure interest. Are you a skier? Well, it's changed that. Do you like wine? It's changed that. I think that [unintelligible 00:06:48] story is just as anybody who is a birder or knows birders, is well aware, they pay a lot of attention to what's happening, it's a very detailed pastime, kind of a focused pastime, and he saw the differences in the sky, it's just undeniable.

Brian Lehrer: Let's take a phone call from Manassa, originally from Pakistan. Manassa in Westchester now, you're on WNYC. Hi, there.

Manassa: Hi. I am originally from Pakistan, and I spent a lot of time in rural Pakistan as well. We are an agricultural society mainly. Since I've been here and go back, I see a difference in the landscape, there are less trees, more buildings, more concrete, and that is considered an advancement, or we are becoming a more advanced society, but, in fact, we are losing out because we're water deficient, our agriculture is going down. There is less and less emphasis on a green society because people are more concerned with their day-to-day needs.

The green spaces are lessening, the landmark is taking over. We have more international companies coming in now into the northern areas where there will be much more cutting down trees and building of new resort areas, which I think is going to lead to more heatwaves and more water deficiencies in the future. Also, with India going back on their deal with Pakistan on how the water from the rivers was going to be split-

Brian Lehrer: Shared, yes.

Manassa: -and what would be given to [unintelligible 00:08:41], that's a problem too, because when the international community stays silent on their own economy, and they don't act as a global village, there will be pockets that are going to suffer. That's going to have widespread impact, not just on the agriculture in the local society, but on the humanity in general, because the same people, if they're hungry, they're not having food, they're going to start migrating, and when they migrate, it's going to cause a crisis in other countries.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, that's right. Manassa, thank you so much. Yes, we did a segment just recently on climate-generated migration that's already taking place, voluntary migration, and refugees. Let's go next to Jennifer in DC. Jennifer, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Jennifer: Hi, Brian. Happy holidays. I wanted to share, I'm Caribbean-American, and my island of birth is very close to the US. We experience everything that we are experiencing. My thought is, and I returned recently, I was not able to come back because of COVID for a while, so I'm back in the US, back home, and I'm looking at the level of ignorance that permeates all of our landscapes. The fact that climate change is real. We have a virus of ignorance coexisting with the COVID. What is going on? Why isn't America taking note and doing something about climate change? These deniers, they really need to be put in a camp. I'm sorry. I'm really feeling really serious about this. My point is let us look within and take care of it right away.

Brian Lehrer: Jennifer, thank you very much. I know we'll take that as a metaphorical camp, lest we get letters and tweeters who think it's something else. Lisa in North Port who used to live in Japan, you're on WNYC next. Hi, Lisa.

Lisa: How are you, Brian? Thanks for taking my call. The issue is the complete drop in the diversity and the number of insects in Japan. It's really noticeable there because the diversity was so high to begin with, but we also see that here. Insects are the bottom of the food chain for all sorts of animals, and a lot of people think, "Get rid of insects. It's fine. No more mosquitoes," but a lot of animals are going to really suffer if there aren't insects around to eat.

What happens is their food resource and their timing of emergence become out of sync. The plants will emerge at one time and then the insects emerge a little bit later because they're using different cues to emerge after the winter, and so they come out and there's no food. That seems to be a big reason why a lot of insects are declining around the world, and it's going to be a big problem for everybody.

Brian Lehrer: Lisa, thank you very much, as we're taking your calls on your end-of-year climate reports from any country besides the United States that you're connected to. Justin in Brooklyn originally from Jamaica. Hi, Justin. You're on WNYC.

Justin: Good morning, Brian. Thank you for taking my call. Listen, I'm from a parish called Manchester in Jamaica, and we have this popular place called Alligator Farm where we go and eat fish and lobsters. Where I used to sit and eat, like 2009, comfortable and these people have the stalls there for years, it's totally underwater today. Like 50 feet under, and they have to keep moving inland all these stalls. To the degree I heard sea level is rising, I see a different result there in Jamaica. It seems like it's going up faster to me.

Brian Lehrer: Justin, thank you very much. As we continue with Meeta Agrawal, the special projects editor for New York Times opinion who led their new project out this week which is inspiring this call-in called Postcards From A World On Fire. Meeta, anything from any of those calls from pretty far-flung places relative to each other that either touches on a country that you mentioned in the article, or that you just want to respond to?

Meeta Agrawal: Sure. I think that what the caller from Pakistan really touched on about local issues becoming-- What's funny about the way we did this project is we focused on 193 countries, but countries are just divided by political borders, the political entities. Climate change doesn't recognize that, and what we saw was a little bit of what she had talked about, about these issues that are going to reach across countries and are going to cause even more political conflict. The fight over water rights when there's less water, there's not enough to go around. That's been an issue, it's going to become a bigger issue.

I think that that's very much something that resurfaced as we were doing this global look at the effects of climate change. Also what the caller in Japan talked about the timing of insects, their rhythms, and their patterns being thrown off. The truth is everything's being thrown off. There's so much of the natural world and even our very, very long-held traditions are pinned to calendars that were really dictated by seasons. As those seasons shift underneath us, as the monsoons are not when they were supposed to be, then all of a sudden, what's been considered wedding season in some countries or when New Years' is often celebrated is all of a sudden during monsoon season, which was never meant to be the case. It's very hard for individuals and communities to understand why that change is happening. I think you have really smart callers, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. We have really smart callers. I will definitely confirm that. This is WNYC FM HD and AM New York WNJTFM 88.1 Trenton WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcong, and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are in New York and New Jersey public radio. A few more minutes with Meeta Agrawal from New York Times opinion. Let's just dot around a few more countries before we run out of time. The feature from Italy is an example of how climate change is changing what we eat. Will bruschetta soon be replaced by mango bruschetta?

Meeta Agrawal: [chuckles] We'll see. We talked to and photographed a family in Italy who has had a lemon grove, lemon orchard for many years in their family. In 2015, what the younger generation noticed was that the climate had gotten more tropical since their great-grandfather had started the orchard, and they realized they could start planting mangoes instead of lemons. I definitely don't associate mangoes with Italian cuisine, but that's what they're growing, and they can sell them at such a higher premium than what lemons go for that it's absolutely worth it. Will we see that trickle down into Italian cuisine? I'm sure we will.

Brian Lehrer: I'm looking at this almost slapstick video on your site for the postcard from the Netherlands. Funny, not funny. Do you know which one I'm talking about?

Meeta Agrawal: Yes, I do. That's a favorite, I guess I could say, of many people's. Canal skating in Amsterdam is obviously something that's very intrinsic to their culture. It's been a motor transportation for just local residents to get to their grocery store. They go ice skating on the canals, but the canals haven't been freezing over and they haven't been able to do that. When they did freeze over, I believe it was this past year, we have video of somebody who went out canal skating and fell through the ice. Now, he was fine. [chuckles] You don't see the second half of the video, but got out. He was totally fine, but while it froze over, it just wasn't thick enough, sturdy enough to sustain a human body. When you think about how it used to sustain an entire city of people skating around, I hope hits home for how much has changed.

Brian Lehrer: Chip in Posey County has a view from above of all of this. Hi, Chip, you're on WNYC.

Chip: Hey, Brian, nice to talk to you. I just ended a 47-year flying career. Started with Pan Am, and ended up with Delta Airlines last year, and the deforestation I've seen every continent except Antarctica is unbelievable. We used to leave out of JFK and fly down to Santo Domingo in the south side of Hispaniola. Back in the '70s, it was probably 90% forested. When we hung up my spurs last year, there wasn't much left, same with Africa and going to Brazil over the Amazon. It's just getting scary. The smoke's coming up all the time, so we got to do something quick before it's too late.

Brian Lehrer: Hey, Chip, how did you even notice it? Because when things change really gradually like the frog who doesn't realize that it's boiling to death in the pot of water, we don't often see it. If you flew over one of those countries one day and it looked one way, the next day you flew again, it would look just the tiniest bit different. How do you even notice?

Chip: I'm talking about a career that's spanned 47 years. Like I said back in the '70s, there was plenty of forestation in Hispaniola, and last year it's probably 85 or 90% gone. It's over the years, you notice it and I was fortunate enough to be looking out the window a lot, but it's pretty scary.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you very much. I really appreciate that call. Before you go, Meeta, two things. One, we talk so much about the harmful effects of climate change, and that is true for the overwhelming amount of the earth, but your project also touched on a community in Canada where climate change might provide a better future. You want to at least mention that one?

Meeta Agrawal: Sure. Yes. In Churchill, Manitoba, there is a port city, and that port is inaccessible or has been inaccessible for much of the year because the water's frozen over. With warming water and less ice means more open water days for Churchill. It means that that port can perhaps become a much more year-round or if not year-round, for many more months of the year it can be open. It can be bustling, and that really changes the fortunes of that community. What we want to show is that there's going to be these trade-offs constantly and that as temperatures warm, that that might be good for some places, actually, but that's in the short term, what's going to happen to Churchill in 20 years or in 40 years, we're in the middle of this transition, but it's already started.

Brian Lehrer: It certainly seems to be based on where people actually live on Earth. A minority of people who might benefit over some period of time, and a large majority of people who would be harmed, not to mention just the disruption from change, and how much the climate change will kill people, frankly, and cause great devastation of other kinds to their lives, even as maybe things in a few of the coldest climates of the world get a little better.

Last thing, for the USA postcard in this global project, I'll tell people, there's a tool where you can enter your county, and it'll tell you what the top climate risk is in your area, spoiler alert, heatwaves Manhattan, Queens in the Bronx, flooding for Brooklyn and Staten Island, if you want to do any county in America that's not one of the five boroughs, you can do it on your own at The New York Times website. Meeta, where does this project go from here?

Meeta Agrawal: Well, what we're hoping is that it'll really connect with people who may not have always engaged in climate science before. We really tried to tell the story in a different way, both through form and content. We're already hearing back from people who are on the frontlines of the fight from teachers, and from readers that I think that, hopefully, there's something in here for everyone, so where does it go from here? Action, we hope.

Brian Lehrer: Meeta Agrawal, special projects editor for New York Times Opinion, thanks so much for joining us.

Meeta Agrawal: Thank you.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.