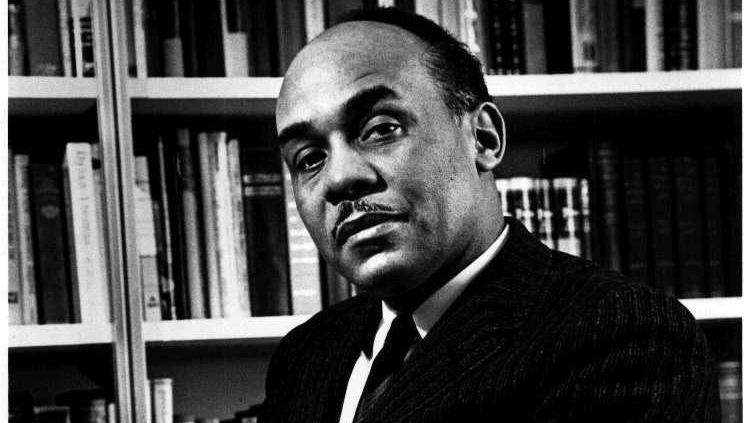

Celebrating Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man

( Wikimedia Commons )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. We're doing Black History Month segments Wednesdays and Thursdays this month. On Wednesdays, it's all about Afro-Latino history. Thanks for your great calls yesterday on your Afro-Latino icons. On Thursdays, it's a variety of Black history topics. Today, we note that this year marks the 70th anniversary of Ralph Ellison's classic novel, Invisible Man, winning the National Book Award for Fiction.

The story has been described as a meeting of realism, and surrealism like how being Black in America can seem both surreal and much too real, how being Black in America can sometimes make you feel invisible, and sometimes much too visible. On the Invisible Man side, the narrator-protagonist is not given a name. What a story with so many twists and turns and themes that will sometimes seem all too familiar to readers with connections to Harlem, and the rural south, for example, even today, to college life, to the health care system, to the tensions in politics between capitalism and socialism is ways forward for Black Americans group versus individual identity. It's all in the book.

We're lucky that our next guests are involved in a series of events beginning today, celebrating the book, it's called Invisible Man at 70: A Harlem Celebration. It's going to continue through the spring with a bunch of different events and discussions about the novel. With us now, Patricia Cruz, Artistic Director and CEO of Harlem Stage, the space on Convent Avenue that's sponsoring this, and Carl Hancock Rux, Associate Artistic Director and Curator in Residence, also at Harlem Stage. Welcome to the show, Patricia and Carl. Thanks so much for coming on today.

Patricia Cruz: Thank you. Can you hear me?

Brian Lehrer: I can hear you just fine. Carl, are you there too?

Carl Hancock Rux: Yes, thank you so much for having us.

Brian Lehrer: Carl, you can hear Patricia, and Patricia, you can hear Carl?

Carl Hancock Rux: Absolutely.

Patricia Cruz: Yes, I can. That's great.

Brian Lehrer: We're all good.

Patricia Cruz: I'm learning technology, Brian. I'm so happy to be with you. I've been a longtime fan of your show. The way you've covered, the breadth of information that you've brought into my home has been remarkable, and I just wanted to say that I'm a fan.

Brian Lehrer: I'm very touched by that. Thank you very much. To start us off, Patricia, can you tell us a little bit about why a whole season of events on one book? Why is it that seminal?

Patricia Cruz: For us, a part of it is, I think Ralph Ellison and many other major artists especially in the African American Black community have been raised up for a minute, some of them, and as you've said, gotten the National Book Award. I think that one of the purposes of what we do at Harlem Stage every day is to really look at and examine the work that has been seminal to our culture. I can't think of a book more seminal than Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man, or an artist more seminal. He really has charted and really laid out a map of our existence in America. As he has said, the aim is realism dilated to deal with an almost surreal reality. I think that that is what this book does. You commented on that as well.

You should know that 40 years ago, I attempted to stage one of the scenes in Invisible Man, The Battle Royale, which I was doing with high school students at the time. It was a complete flop, of course, because the work is so massive, there was no way that we could capture it. Those images from this book have lived with me for over 50 years, and I was determined to do something about it. We came into a wonderful relationship with the Maysles Documentary Center, and Dale Dobson. We came together to say Invisible Man, yes, this is the 70th anniversary, let's do something big. Then we brought six Harlem institutions together to celebrate this work.

In answer to your question, the idea of celebrating this book in Harlem is critical because for those who have read it, and those who I hope will read it as a result of this performance that we're doing in this celebration that we're doing, will understand how much Harlem is the set for this novel. Once he leaves the south, he's in Harlem, and around New York, of course. For us to work together with these organizations, the Studio Museum, the Schomburg Center, the Ralph Ellison Memorial Committee, and the National Jazz Museum, is just a joy, a dream come true.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we invite you in. If you read Invisible Man, what does the book mean to you today? 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Carl, you want to just keep going and pick up where Patricia left off?

Carl Hancock Rux: Sure, absolutely. I think that there's a history that should be acknowledged about Ralph Ellison and his relationship, not only to Harlem but to the writing of this book. He arrives in Harlem a year after the Harlem riots of 1935, which is really considered to be the first contemporary or modern riot of the 20th century that involves African American people, in that it was not a riot, specifically, between Black and white people, but it was a riot that was in response to racial injustice, racial discrimination, and unfair employment practices, and housing practices, and all of those things.

There was an organization that helped fuel that Harlem riot of 1935. Three people died, there were over 200 people or whatever who were arrested during that riot. It signified the end of the Harlem Renaissance. That glorious period where we all thought Harlem was feathers and sequins, and jazz music, and everything was fine and everything was beautiful, and white people were coming from downtown and hanging out uptown to "slum." For me, it has so many allusions to even the Black Lives Matter movement in a way or other movements, or riots, or events that have happened, that have been about announcing an injustice against the people in an organized way.

Brian Lehrer: Amy in Manhattan is calling in with a particular scene that sticks with her from the book. Let's find out what it is. Amy, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Amy: Hello. It's been a long time since I read the book, I was in high school and around the end of the '60s. There's [unintelligible 00:08:22] character falls in with leftists, maybe even communists. There's a scene where he's at a party, some kind of gathering and there are people from the left and the right, I think. Some of the people voted more to the right and asked him to sing. One of the leftists is like, "My brother does not sing." It's interesting to see how-- I wonder how often it happens in real life that the people who might even be well-meaning presume to speak for Black people. [unintelligible 00:09:07]

Brian Lehrer: You want to take that, Carl, or do you know the scene that she's talking about?

Carl Hancock Rux: I do know the scene and I just wanted to say that after the depression of 1929, there was a huge movement. Actually, there was a huge movement of a communist and leftists all around the country and certainly in Harlem. I think what is little known is that there was a very big community of African American communists or people who were beginning to join the Communist Party or become interested in it or even people who had not joined the party but were interested in another form of democracy other than the one that we were all adhering to. Ellison was one of those people, and he, along with writers like Richard Wright, who was his mentor.

They both had become disillusioned with the Communist Party because they felt that the party was not really addressing race issues in the way that it should be. In fact, Ellison's book is not only a response to the race riots of 1935, but it is also a response to Richard Wright's book Native Son in that he feels that Richard Wright leans on a Marxist-Leninist approach to excuse Black criminality or African American criminality or what's happened in the Black community.

Ellison does not feel that that's the point, that it's not a Marxist-Leninist philosophy or theology or any such thing. Ellison finds his own voice in writing this dystopian science fiction that is not such a science fiction but is absolutely rooted in a realism that speaks to what Black people were thinking about and talking about and dealing with at the time.

Brian Lehrer: You talk about the tension or just public disagreement that existed at the time between Ralph Ellison as a writer and Richard Wright, who wrote Native Son as a writer. I actually pulled a couple of clips of Ellison so we could hear his voice in this conversation. These are both from a 1966 interview on public television. One of the clips, he doesn't mention Richard Wright by name, but it goes to Ellison's thought about the place of the writer in society. We will hear him in this minute or so clip, talk about not becoming explicitly political spokespeople as writers. Here's Ralph Ellison.

[start of audio playback]

Ralph Ellison: I think that the nation is still in a process of becoming, of drawing itself together, of discovering itself. When the writer fails to contribute to this, then he's-

[end of audio playback]

Brian Lehrer: I apologize, that was my fault. That's the other clip that I pulled of Ralph Ellison. We're going to play that one in a few minutes, but let's hear the one that I was setting up.

[start of audio playback]

Ralph Ellison: You can take advantage of all of the theories, all of the insights, of anybody that we burke through Emson to Sir James Frazer but you still got this crazy, highly mobile country with ever damn thing happening. About the only people who are not trying to deal with it, seem to be novelist. This is unfair in a way, but not so very unfair.

I would, as a kid, listen to the Pullman Porters when they started telling what was happening up the line. You knew that you were the same people living in Oklahoma City as against those who were living in St. Joe, Missouri, or Chicago or Kansas City, but you also knew that things were a little bit different in Kansas City. Kansas as against Kansas City, Missouri. They were Twin cities, so to speak, but they were always reporting the variety and always giving you a report on the manners but God, you could pick up novel after novel after novel now, and you get a sense that there's no United States out there.

[end of audio playback]

Brian Lehrer: Now, I apologize because I got my two clips all jumbled up. I was actually right the first time with the one that we started. The one we just played was Ralph Ellison in 1966 on public television, on what he saw as the detachment of writers from the diversity of American life. Here's the one on not becoming explicitly political spokespeople.

[start of audio playback]

Ralph Ellison: I think that the nation is still in a process of becoming, of drawing itself together, of discovering itself. When the writer fails to contribute to this, then he's played his art falls. I think that he probably also does violence to our political vision of ourselves because usually when a writer becomes a political spokesman, he speaks out of context. He doesn't have the disciplinary forces behind him. He leads nobody really. There's no one to say no to him. He floats on a sea of publicity and on the easy availability of the big media, so to speak.

[end of audio playback]

Brian Lehrer: Patricia Cruz, do you want to comment on either of those? I think we learn at very least, people who haven't heard Ralph Ellison speak before. How thoughtful and introspective and a deep thinker he was on the place of the novelist, the place of the writer in society.

Patricia Cruz: Yes, I love it. I love hearing that because I had not heard those clips before, Brian, so that's wonderful. A couple of things come to mind. My grandfather was a Pullman porter and it's so interesting to me to see how those individuals at that point saw the entirety of America. That really is what Ralph Ellison does. I think that a part of it is like Faulkner, he can take a piece of what he knows and then explode it out so that you see the whole country and its complexity and in its richness, but also in its failings.

I think that was one of the things that he wrote about so clearly. That's one of the reasons that so many people during the period that we were talking about earlier had started to look toward communism to see something that would represent a fairer form of economic equity that could be experienced by both Black and white folks and all of the people who are in America. I think they got disillusioned, as Carl has said, but clearly, Ellison was dealing with the whole journey from the southern schools into Harlem, looking at both the despair as well as opportunity because he was so smart in looking at those things.

Brian Lehrer: If just [crosstalk], go ahead, finish. I'm sorry.

Patricia Cruz: I was just going to say that the other part of it is there's a real joy for us at Harlem Stage as we present the readings and music that we will be a listening session and this is going to be tomorrow night. Carl Hancock Rux, who has joined us as an associate curator and artist with us is going to be reading, and we will be working with Ryan Maloney of the National Jazz Museum in Harlem to have, they've collected and received Ellison's record collection. What we'll be doing is alternating between readings from Ellison's book and then hearing and listening to the music that he collected.

Brian Lehrer: Wow.

Patricia Cruz: We're hoping to have a whole picture of Ralph Ellison tomorrow night at Harlem State.

Brian Lehrer: I want to go to some great looking call who we have, but you've got to tell me what did he listen to?

Patricia Cruz: He had a large classical collection. He had a ton of Duke Ellington and I was surprised because he was fairly conservative in his musical taste, but he had Ornette Coleman's The Shape of Jazz to Come. We're listening to Money Jungle, which is a part of Duke Ellington's work. We're looking at Come Sunday with Mahalia Jackson singing with Duke Ellington's Orchestra.

A lot of Ellington. He had a great deal of respect for him. Some blues as well. He had Count Basie. We'll be listening to a lot of that music and showing the album covers because that's what has been bequeath to the National Jazz Museum. We are working together out of the larger collaboration, we're working together on the first program that will really introduce an entire series of programs that will go through the remainder of this season that are being produced by our colleagues at these other institutions.

Brian Lehrer: We had a lot of classics and he also had the more avant-garde shape of things to come. Listeners, if you're just joining us, we're talking about Ralph Ellison's 1953 National Book award-winning novel, the seminal Invisible Man at 70 years old with Patricia Cruz and Carl Hancock Rux from Harlem Stage. As Patricia was just saying, one of the organizations participating in a series of events that begins today celebrating Invisible Man at 70. Kwame in Chicago. You're on WNYC. Hi, Kwame. Thanks for calling us from Chicago.

Kwame: Hi. Thanks. My foundational trilogy includes Ellison and Wright. It starts with Black boy, native son, which tells the story of my father and grandfather, and then Ralph Ellison tells my story. I think those clips that you called the wrong clips were the right clips. I think he resolved the tension there, but I called in to say the reason I read the book over and over again is that it reminds me of a privilege I have.

I connect Ellison to his -- The key quote for me is he says, "I'm invisible because you cannot see me." I connect that to Dubois's statement that the Negro is gifted with the second sight. I always feel like I have this ability to see in at least two dimensions, whereas I feel like a lot of white readers don't get that from the Invisible Man that they don't see their blindness. I'll just stop there.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, I think there's a concept that almost in any society, probably extremely in the case of African Americans, but almost in any society, if you are in the minority, you have a kind of double vision. You can see the majority in a way that they can't see themselves because they are the majority. What they do, what they think, what they see just looks normal to them and universal. That's a wonderful point to raise. Kwame, thank you very much. Let's go on to Deborah in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Hi, Deborah.

Deborah: Hi. I am a very long-time listener. Wow.

Brian Lehrer: I'm glad you're on.

Deborah: You and I go way back long time. I truly admire you. You have such a profound influence on the thinking of New Yorkers, and I'm grateful for that.

Brian Lehrer: Very kind.

Deborah: I read Ralph Ellison. As a 13-year-old kid living in San Antonio, my family was military, so we had moved around the country and we had just moved away from Albany, Georgia, where the Albany movement was going on. Ralph Ellison really helped me to have a clear understanding of what it means, as the caller ahead of me was saying, to be in a situation where you have two perspectives on where you are in the culture. What I came away from that with was the understanding that I not only belonged to the dominant culture, I'm a member of a subculture. He, like Morrison, who came later, helped me to move out of the white gaze in terms of determining for myself who I am and my value.

Brian Lehrer: Deborah, thank you so much, and I'm glad you finally called in. Please call again. One more in this set. Lester in Manhattan, you're on WNYC, who I think he's going to say met Ralph Ellison in person. Hi, Lester.

Lester: Yes. After the success of Invisible Man, Ralph Ellison made a lecture tour around colleges around the country, and he stopped at my college, Antioch College which was a radical college at the time, and still is probably. He gave a lecture on American literature, and the next morning in the cafeteria, he was having breakfast by himself. I sat down at his table to speak to him, and he was very welcoming. I must say I was a cocky kid, and I was never impressed by professors and things like that, but the guy radiated pure intelligence. It was almost scary.

[crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Do you remember any individuals?

Lester: Yes. What I was going to say was that he mentioned that he was forced by his editors at Radnor House to cut over a third of the manuscript of Invisible Man.

Brian Lehrer: Wow.

Lester: Which explained to me why I found it part of it structurally as disjointed. I often wondered whether the original manuscript ever existed. Still exists.

Brian Lehrer: Interesting. Lester, thank you so much. Carl, I don't know if you know the answer to his question, but isn't it wonderful as we celebrate the 70th anniversary of this book to hear from all these older callers who've been influenced by it their whole lives?

Patricia Cruz: Yes. Carl, are you still with us?

Brian Lehrer: Oh, did we lose Carl's line?

Carl Hancock Rux: Oh, no. I'm sorry. I had muted myself, but here I am. I'm back. Yes. I absolutely hear you. I was raised by my father, I was born in Harlem in 1915, which is a year after Ellison was born. My adopted father, so he is much older than me. I inherited, I think, a history that was concomitant to Ellison's reaction to the world in a way, or at least the experience of African Americans. For me, reading this book, and not to disagree with the caller at all, but just for me, I don't know that I find the novel to be disjointed. I find that it was in response to one H.G. Wells' scientific novel, a science fiction novel from the 19th century.

Brian Lehrer: Called The Invisible Man. Right?

Carl Hancock Rux: The Invisible Man, exactly, right. Where a scientist devotes himself to research into optics and invents a way to change a body's refractive index so that air neither absorbs nor reflects light. I think he was saying, "Well, this is a perfect metaphor, really for Black people." I think that's what Ellison was talking about. I would love to know where the remainder of the manuscript exists, but it is full and complete for me.

Patricia Cruz: What I was wondering-

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead, Patricia.

Patricia Cruz: -was I would just love it if Carl has an opportunity to read a short passage from Invisible Man, because I think your listeners will get another sense of the writing, but also to get a preview of what we'll be doing tomorrow night with Stephanie Berry and Ty Jones joining him in the reading.

Brian Lehrer: Oh, that would be-

Patricia Cruz: Is that possible?

Brian Lehrer: -such a treat. Carl, do you have anything at your fingertips like that?

Carl Hancock Rux: Sure. Absolutely. I would love to. I'll read the beginning of the book. Here it goes da da da, I'm finding it. It says, "I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allen Poe, nor am I one of your Hollywood movie Ectoplasm. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids, and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows.

It is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard distorting glass. When they approach me, they see only my surroundings themselves or figments of their imagination. Indeed, everything and anything except me, nor is my invisibility exactly a matter of a biochemical accident to my epidermis. That invisibility to which I refer occurs because of a peculiar disposition of the eyes of those with whom I come in contact.

A matter of the construction of their inner eyes, those eyes with which they look through their physical eyes upon reality. I am not complaining, nor am I protesting either. It is sometimes advantageous to be unseen, although it is most often rather wearing on the nerves." [crosstalk] Yes, I'll stop there.

Brian Lehrer: What a classic opening. Just as you were talking about how he was influenced by H.G. Wells, The Invisible Man, I believe he was influenced by so much, right? Like by [unintelligible 00:29:24], people have said, from notes from the underground, which starts, "I am a sick man." People think it was a riff on that, opening the book with that first line you read, "I am an Invisible Man." I don't know if that's your take.

Carl Hancock Rux: Absolutely. I think he was also responding to Langston Hughes's poem, What Happens to a Dream Deferred. You're speaking about the interiority of invisibility, the interiority of blackness, the interiority of not being seen or understood or heard or even being not really considered a full American while living in America.

Brian Lehrer: Let's end just by inviting you, Patricia, to tell people how to find out about the events in this series, celebrating the 70th anniversary of Invisible Man. I know that one of the events today is about poetic contributions, responding to the question, invisible to whom? Maybe start there and say what else people can see, or just where they can find out information about the whole set.

Patricia Cruz: That's one of the programs and thank you so much for allowing me to do that, Brian. There is a page on our website that all of us have. It's called HTTPS\InvisibleMan70Harlem.org. There is one landing page in which people can find out about these programs. Certainly, one can go to the Harlem Stage website, Harlemstage.org, and you'll have a whole collection of all of our programs, which are very much connected.

I did want to say that as well. Tomorrow night, we'll start at 7:30 with the reading that Stephanie Berry, Ty Jones, and Carl Hancock will read. Then following that, there will be programs that unfold across Harlem, and we do hope that people take advantage of all of that. Also, this fits in, I would say, quite nicely to a series that really Carl has conceived.

I think your listeners should know that Carl is a highly published and noted novelist and poet performer, and we're very proud to have him. He has had a 30-year relationship with Harlem Stage, just as we're about to embark on our 40th anniversary.

We've got a lot of programs that he has conceived on the Black Arts movement, and I think, interestingly, we will follow the program that we're doing this weekend with the program next weekend with looking at We Insist by Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln. There is really a connection between everything that we're doing. We hope that your listeners will be able to join us because we have fun.

We have fun because we sit at the intersection of art and social justice. There's a real link between all of the programs that we're doing, and we're thrilled to have Carl be with us. We are the beneficiaries of a Mellon Grant, and I know you had Elizabeth Alexander on your show recently. That was fabulous. There is a connect-- We're all connected, Brian, in this effort to have art show us the way. I think Ellison is a critical voice to do that.

Carl Hancock Rux: I should say that I'll also be in conversation with the writer Ishmael Reed, about the work of Max Roach the week after we're doing Ellison. As well as, having musicians and artists reinterpret the music of Roach. Pat is absolutely right, all of this is a continuum of Ellison into the Black Arts movement into the now.

Patricia Cruz: Yes,

Brian Lehrer: Patricia Cruz and Carl Hancock Rux. This was really special. Thank you both so much for joining us for this today.

Carl Hancock Rux: Thank you so much.

Patricia Cruz: Thank you for having.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.