Celebrating Juneteenth with Max Roach's Story and Music

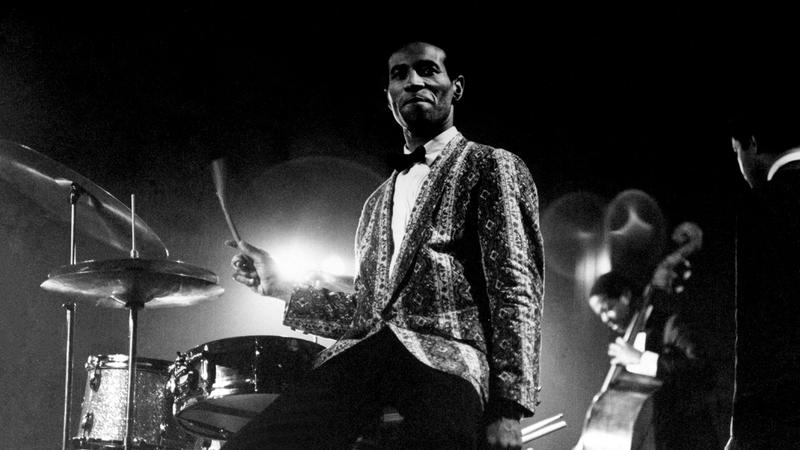

( The Max Roach Collection, the Music Division, The Library of Congress / courtesy of Rooftop Films )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. This weekend at Vaughn King Park in Brooklyn, Rooftop Films will hold a screening and live music event pegged to the centennial of the birth of drumming icon Max Roach. The film is called Max Roach, The Drum Also Waltzes and Von King Park is right by where Max Roach grew up in Bed-Stuy. Here's a remarkable short clip from the film in which Roach, who was also very committed to civil rights and the Black community, drums to Martin Luther King's I Have a Dream speech.

Martin Luther King Jr.: I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its dreams. We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equally.

Brian Lehrer: Martin and Max there. As for those of you not familiar with his music, maybe get a hint of both what an original artist he was and why this film is being screened in Brooklyn in the context of Juneteenth weekend observances and celebrations. We'll hear a few more clips as we go, and as we're honored to have the filmmakers, Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro, co-directors of this film, Oscar-nominated Sam Pollard is the director, producer, editor of so many great things.

He's got another new documentary at the Tribeca Film Festival right now called The League, about the Negro League in baseball. He made Mr. Soul a few years ago about the first major late night Black television show called Soul on public television way back when with a host Ellis Haizslip. He made Sammy Davis, Jr.: I've Got to Be Me in 2017. He produced the seminal documentary about the civil rights movement Eyes on the Prize for PBS going all the way back to 1990.

Sam Pollard is with us, and co-director Ben Shapiro, Emmy, DuPont, and Peabody winner documentarian who works in film television and very much in radio and podcasts, I should say. His work has been heard here in conjunction with Radio Diaries and many public radio things. The Drum Also Waltzes is a real biopic and a really great story, whether you already know of Max Roach or not. Ben Shapiro and Sam Pollard, an honor, like I said, to have both of you on the show today. Welcome to WNYC.

Ben Shapiro: Thanks for having us.

Sam Pollard: Thank you very much, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Sam, the title, The Drum Also Waltzes, it was certainly waltzing in that clip of him with Martin Luther King. Musically speaking, one of the things that comes through so clearly in the film is that Roach, maybe more than anyone ever, uses the drum as a lead instrument, not just an accompaniment to keep the beat, which might be the way that most people think of drums. Can you talk about his relationship with the instrument and with sound?

Sam Pollard: That's exactly what the Max was all about. It wasn't just about keeping time, which was important to him, but it was also about making sure people understood that the drum kit was an instrument just like the saxophone, just like the trumpet, that could be musical, that could be melodic in his approach. The Drum Also Waltzes is a name of a composition that he wrote to make people understand that drums could be front and center, as you said. If you listen to Max playing from Charlie Parker all the way to playing with Cecil Taylor, he was able to use the drums in ways that made the instrument just front and center in all of his musical iterations.

Brian Lehrer: Ben, as the MLK clip exemplifies, I think Roach was into politics and communicating the Black experience through his music as one of the things that he did. With that remarkable clip in mind, here he is talking about that side of him. [crosstalk]

Ben Shapiro: Yes, that clip-

Max Roach: I became an advocate, I guess, politically speaking. We thought the country was going to change and things were going to be better in education and labor and equality and all this. It was like that dream that everybody was hoping would happen. I got caught up in it intellectually, emotionally, and musically. Since I had the stage and I was recording, if I could say something, I said it, whether it was through my music or whatever, because I have a stake in this country as well as anybody else.

Brian Lehrer: A clip of Max Roach, speaking from the movie Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes. Ben, can you talk about Max Roach as a political artist?

Ben Shapiro: I think as he talks about there, he became particularly involved in the civil rights movement in the 1960s. As we heard in the piece with the I Have a Dream speech, that really encapsulates a lot of his approach. As Sam said, bringing the drums front and center and also using music as a way to engage with the civil rights movement and with the issues that he was facing at the time as a musician, as an artist, as a Black man in America. Also, you can go back to his career even before that, in the 1950s, he started one of the very first record labels, I think maybe the first record label that was started by a jazz musician.

He had a really long-term commitment, even before the 1960s. One thing we see is, in the 1960s, he created this remarkable body of work, as we see in the film of music. There's one piece that is featured prominently in the film and that's performed widely still today called The Freedom Now Suite, that traces the experience of African Americans throughout a long history. That was just work that he did in terms of using his art to explore those issues and bring them to an audience and also merge them with his creative art.

Brian Lehrer: On the Freedom Jazz Suite, I think that's the record that's referred to in the film by one of your sources, Sam, as one of the first ever protest records. Yes?

Sam Pollard: Exactly. That's what it was. It just shows you that Max wasn't just about wanting to be a swinging drummer who played Vee Bobby, Charlie Parker, or played [unintelligible 00:06:52] Brown. He was an activist drummer. He was a drummer who said, "I want my music to have a message. I want it to mean something." When he created the Freedom Now Suite, he had such great new musicians play with him, like Coleman Hawkins and Abbey Lincoln. It just shows that Max always understood that the music was just not about tapping your feet, it was about also providing a way to produce a message.

Brian Lehrer: Although, Sam, I'll stay with you on this, there's a great quote in the film about Max using music for politics, but I think the phrase was, "But usually for joy." I wonder if you can expound a little bit on how those two things intersect in his work. People may think, I don't think, but people may think that those things can be the opposite of each other.

Sam Pollard: No, they don't have to be separate at all. Max understood that you can make the music swing, but you could also make the music have some meaning beyond just swinging. If you listen to the the music in Freedom Now Suite or listen to any of the albums he did in the '60s, like Percussion Bitter Sweet or Time, Max is always a swinging drummer, but he was always putting across his message. The music's infectious. I loved Max ever since I got him to the music at the age of 17, and you can hear the joy and the excitement that he loved in performing his music, and he performed for over five decades his music.

Brian Lehrer: You also have a quote, Ben, of record producers and concert promoters wishing that Max would talk less at his concerts and play more. It reminds me of when the conservative Fox News host, Laura Ingram, just a few years ago suggested that LeBron James shut up and dribble, but was it that bad?

Ben Shapiro: Yes. He paid a real price in terms of being able to get gigs. He had been with a major record label up until one point in the 1960s when he was dropped by the major label and didn't have another one for many years. That was the reality for him and ultimately led to him taking a teaching job. He really faced that pushback from club owners and from record labels and promoters, because he was outwardly committed to his politics

Brian Lehrer: On mixing really great music with politics, very poignant and timely. Right now you have several clips of Harry Belafonte talking about Max's place in political music. Sam, did they have a relationship or ever collaborate that you know of?

Sam Pollard: Yes.If people don't know this, within the late 1940s, Harry was a jazz singer and he performed at some clubs with Charlie Parker and Max Roach and Tommy Potter. He knew Max for a long time. Then when Max became active in the '60s, they'd start to really engage even more back in that period also. Harry knew Max for quite a long time.

Brian Lehrer: I'm curious, just as a jazz fan, if either of you know anything about his musical relationship with Miles Davis. They were both in Charlie Parker's band in the bebop era. You have footage of that. There's one reference in the film to people wanting Max to go electronic like Miles did in the late '60s and '70s, and Max wasn't interested. To me, Miles was another giant of originality, along with Max, just in his own ways, fusing jazz with rock.

Like Bob Dylan in his genre, Miles took a lot of heat, as I'm sure you both know, from traditionalists for plugging in and going electric. He was also very Black experience identified. Max was constantly original in different ways. I'm curious if you saw them as artistically competitive or with mutual respect in that late '60s into 1970s period. Sam, do you have anything on that?

Sam Pollard: Yes, here's what I would say. Max and Miles were the two young acolytes who were surrounded by Charlie Parker, and he had that band in late '40s. They became very close friends and they stayed close friends all through the years. Even though they went in different musical directions by the late '60s, Miles and Max still were very close friends. They weren't competitive. They just had different musical directions. I think probably the only tension that they ever had was when there was a concert that Miles had and Max protested, but other than that, they stayed close as musicians and as friends for years.

Brian Lehrer: Wait, Max Roach protested a Miles Davis concert? What was that about?

Sam Pollard: Yes, there's a picture that we have in the film, and it was from a concert that Miles had performed at. I think Max was protesting something about South Africa, and it was a Miles concert. It's the only time that I ever knew that there was some tension between them from that direction. They were close for years. They're very close for years.

Brian Lehrer: Here's another clip that demonstrates Max always searching. I love this. After going through his periods of bebop and then more conceptual and civil rights-focused jazz, here he is in the '80s celebrating and participating in music that many of his conventional jazz peers denounced, rap.

Max Roach: When the rap craze came, it was another thing that excited me because I said, "Now, this is the same thing I've been working on all these years." Because what they did was just use rhythm without using the rules of music theory. When my peer say, "Max, you're dealing with these rap, that's not music." I say, "It may not be music, but it's part of the world of sound that music is part of it." It created something that was very valid for me.

Brian Lehrer: Pretty remarkable. Ben, what was the context for that clip?

Ben Shapiro: In the film, the context is Max is actually the godfather of hip-hop pioneer Fab Five Freddy. Max was approached in the 1980s to do a performance at the kitchen performance space. He asked Fab if they wanted to do something with him, and so they did this joint performance, where there were rappers and DJs and Max was there playing the drums. They did this performance and it was a landmark at the time.

I also think it speaks to what Sam was saying earlier, that Max was always about the new and the next thing, and was always interested in the new and the next thing, and always interested in broadening the palette of what music could be. For him, as he says in that clip, it could incorporate a wide variety of things beyond the conventional melodies and harmonies that we might associate with "jazz". He was always exploring. We see that over the course of his five-decade career.

Brian Lehrer: Ben, let's talk about the screening coming up this weekend in Brooklyn. Where and when? Tell our listeners who might want to attend.

Ben Shapiro: It's in the park. I don't have the schedule in front of me. I know there's a music before that coming up, and I think the screening is at 9:30, I believe. Hopefully, you can tell that in a more accurate way than I can.

Brian Lehrer: I'm going to have to look that up myself. I think I remember that. It's Saturday?

Sam Pollard: It's this Saturday, June 17th. There's going to be a performance in the park from 7:00, 7:30, seven to eight o'clock. There'll be a little discussion introduction. The film will be shown with dark at nine o'clock. I'll do a Q&A. Ben won't be there. Ben will be in Sheffield screening the film. I'll be in Bed-Stuy screening the film. We're close to where Max grew up.

Brian Lehrer: I see that the two of you will be doing a Q&A. Both of you at the screening, is that [unintelligible 00:15:15]

Sam Pollard: No, I'll be doing the Q&A because Ben will be in England screening the film.

Brian Lehrer: That's great. I'm seeing doors open at 7:30 at Von King Park, film at 9:00, and audience, listeners, you can RSVP at rooftopfilms.com, if you want to go. Rooftop Films is putting this in a Juneteenth weekend context. Maybe there's nothing more that we need to say after the conversation we've been having about Max's life and work, about why-

Sam Pollard: That says it all, Brian. That says it all. Juneteenth is important for this country and for the Black community. This seems the perfect connection to screen Max and film at the park on June 17th.

Brian Lehrer: Ben, I'm seeing that the park is steps, as the press release puts it, from where Max grew up in Bed-Stuy. What was his Bed-Stuy childhood like? Do you get into that in the film?

Ben Shapiro: We mentioned a little bit. We don't talk about a lot in the film, but that community was it. It was an interesting place at that time, of course. His father we know had a political interest, was a follower of Marcus Garvey. It's noteworthy that the film was both screening there and that Max came out of that community.

Sam Pollard: The other thing to know that, Brian, other great jazz musicians came out of that community, too, like Cecil Payne and Randy Weston. It was a community that was a great incubator for great jazz musicians, also-

Brian Lehrer: There is going to be live jazz at the screening, right?

Sam Pollard: Exactly. There will be live jazz. Yes.

Brian Lehrer: Let's see. Oh, it's a Luther Allison trio presented by Jazz at Lincoln Center collaborating with Rooftop Films on this, so that's awesome. The film, again, is Max Roach: The Drum Also Waltzes. We think, the co-directors, Sam Pollard and Ben Shapiro so great to have you both. Thanks for talking about this.

Sam Pollard: Thank you, Brian. [crosstalk] Enjoy your day.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.