A Call to End Parole and Probation

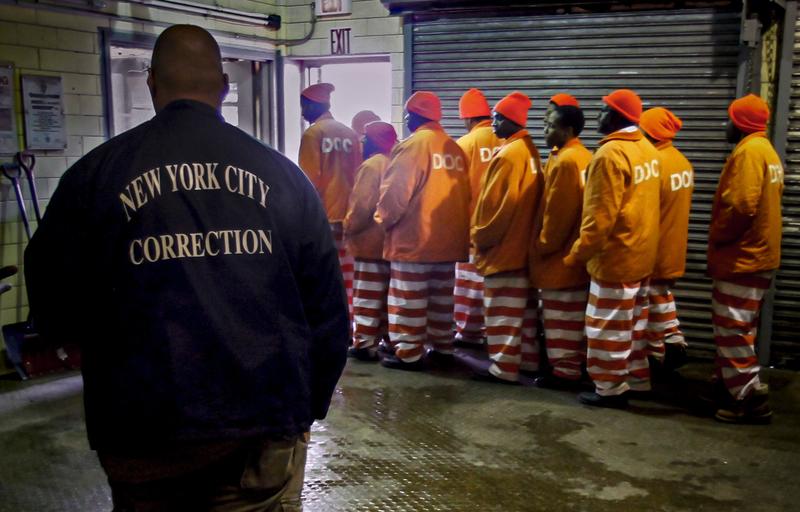

( Bebeto Matthews / AP Photo )

[music]

Announcer: Listener-supported WNYC Studios.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. It's been two years since Governor Kathy Hochul signed the Less Is More Act, which modifies the standard of evidence and certain other procedures when determining whether to end the community supervision of a person on parole. The website lessismore.org reports that more than 5,000 people are incarcerated in the state's, jails and prisons for non-criminal technical violations of parole, like missing curfew or an appointment with a parole officer. Up until 2021, New York State incarcerated more people for parole violations than any other place in the country according to the governor.

Our next guest makes the case to abolish parole and probation saying it does not positively impact incarceration or crime rates. No, he's not an activist, at least not technically. Vincent Schiraldi was the Commissioner of the New York City Department of Probation from 2010 to 2014 and was appointed Commissioner of the City's Department of Corrections in 2021. That is, he ran Rikers as a reformer at the end of the de Blasio era. Now he's secretary of the Department of Juvenile Services in Maryland, and he's the author of a new book titled Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom. He joins us now. Vincent Schiraldi, always good to have you on. Welcome back to WNYC.

Vincent Schiraldi: Thanks for having me on again, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Before we get into the book, can I just ask if you heard that lead story in Michael Hill's newscast, just now, as former correction commissioner, about live insects found in mashed potatoes at Rikers? I'm just curious if, to your knowledge, that would reflect anything systemic.

Vincent Schiraldi: Things were so systemically awful at Rikers for my brief seven months there that it could be idiosyncratic. I think the folks that are advocating for the closure of that awful place and for a federal takeover are on the right track. I've seen other jurisdictions where the leaders, they are actually, acquiesce to and even engage in negotiations around how receiverships could be structured. I know that by the time you become mayor or commissioner of a big place like New York City or a big system like Rikers, you don't want to give up any part of that.

I think, really, people need to take a breath and think about what's best for the city, what's best for people who are incarcerated there, what's best for public safety. I think closing that place in the receivership are two top things that should be on that list.

Brian Lehrer: One more Rikers question then before we get to the book. Mayor Adams recently asked City Council to revise the current law that would close Rikers by 2027 because he says, with the increase in the incarcerated population, with a spike in crime since the start of the pandemic, there aren't enough other beds to put the people in with the anticipated numbers by 2027. I'm curious if you have a reaction or a solution to that.

Vincent Schiraldi: Yes. Getting the population right at Rikers is something that you really need to roll up your sleeves to do. Towards the end of the de Blasio administration, actually, towards the middle of the De Blasio administration, Liz Glazer, who ran the Mayor's Office of Criminal Justice, was doing just that with her team and with the judges and the prosecutors and defense attorneys, and advocates. It really is about taking a look at all the populations there, seeing who can be safely diverted, and most importantly, moving case processing along.

Almost the vast majority of people at Rikers are waiting for their cases to be disposed of, to get convicted or acquitted, or their cases dropped, and if sentenced, to serve their sentences at Rikers, or mostly, to go upstate. It's this really not a set them loose moment here. It's a make the system more effective and make it run better moment, and that should be equally embraced across all ideological spectrums. Nobody should want this system to run inefficiently and slowly. If it was able to move more quickly, then we'd be easily able to fit the population into the four proposed jails that are approved through the ULURP process.

Somebody needs to manage now, not politicize. Step on the gas on construction, work with the courts and prosecutors and defense attorneys on accelerating those cases, and set targets, and hold people accountable for those targets. It's a real management moment, and I wasn't pleased to see a request to slow it down because that suggests that they're not managing towards that end.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you for that. All right. Your book is called Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom. I see you and your colleagues analyze 40 years of supervision data, as you call it, from all 50 states. What did you find?

Vincent Schiraldi: We found that this system of probation that was supposed to divert people at the front end or parole that was supposed to get them out of prison early because they participated in programs and behaved well in prison was originally designed to be both rehabilitative and to reduce the use of incarceration. Neither of those things are true anymore. The system took a turn for the more punitive during the last four decades of mass incarceration, during which we simultaneously had mass supervision and now probation and parole are not being shown to reduce re-offending. They're being shown to increase the number of people in incarceration. Quite the opposite of what they were originally designed to do.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe it's worth distinguishing for listeners not familiar between probation and parole. How are they different, and does it matter to this conversation?

Vincent Schiraldi: It matters a bit, yes. Probation was started in the 1840s by a bootmaker in Boston named John Augustus, who went to court and started bailing people out as an alternative to them getting sentenced to the dangerous House of Correction being run in Boston at the time. Parole was started later in the US context, in Elmira Penitentiary, upstate New York by Zebulon Brockway as a way to take a look at folks who had been behaving well and participating in programs and incentivizing them by offering them early release on supervision.

Most of the book focuses on what happens on supervision, however and in the '70s and '80s, and '90s when we began to get "tough on crime," instead of focusing on rehabilitation, we focused on violating people and returning them to prison for small missteps like missing appointments or staying out past curfew, or associating with somebody else with a criminal record. That's been filling our prisons ever since.

Brian Lehrer: For example, you write about how supervised people get stuck in a "recidivism trap." One famous recent example you write about is Philadelphia rapper, Meek Mill. He was on probation stemming from what I believe was a false charge that he pointed a gun at police officers when he was 18 years old. His probation lasted over a decade. Let's take a listen to how he described it back in 2018 when he spoke to Trevor Noah on The Daily Show.

Meek Mill: If I decided to cross the bridge to go to New Jersey without calling my probation officer with forgetting, I could actually go to prison, or if I got pulled over or got a traffic ticket, police contact is a violation. If I come in contact with the police and the judge decides that she don't like the contact that I came in with police, it doesn't have to involve a crime. You could be innocent. I got sentenced to two to four years for popping a wheelie. I got arrested in New York for popping a wheelie, which actually they charged me with a F1 felony.

When I went to court, the case was thrown out. I didn't even get a traffic ticket for popping a wheelie. I still was sent to jail for that, you know what I'm saying? Just police contact on probation is really jail time basically. For people that look like me and come from the environments I come from, police contact happens on a daily basis.

Brian Lehrer: You want to go into that? That was Meek Mill on The Daily Show with Trevor Noah, a few years ago. What about Meek Mill's story resonated with you that it wound up in your book?

Vincent Schiraldi: Yes. People on probation and parole are only conditionally free, and the early decisions about it that still guide practice today happened in the '70s before mass incarceration, at a time when the probation and parole were thought to be friendly approaches. If this is a friendly activity, Brian, between you and me, and your job is to help me turn my life around, the last thing we want is a lot of due process nonsense in between you and me. Because you're trying to help me find a job, you're trying to help me kick my drug problem, you need to go into my apartment, be able to look through my drawers, and make sure that I don't have cocaine hiding in there.

That's the sort of theory behind all of this. Then when we launched the war on drugs with Richard Nixon in 1972 and things started getting harsher and harsher, 1973 Rockefeller drug laws, and this became a very salient issue, it stopped being a helping practice and became largely a surveillance practice. Now you're not just looking in my underwear drawer to find my cocaine so you can help me kick my habit, you're doing it so you can send me to jail. Now a quarter of the people entering our largest in-the-world prison system every year, enter not because they committed a new crime, but because they're being imprisoned for technical non-criminal violation of either probation or parole.

When I was in New York, I was speaking a lot about this. I taught classes at Columbia before I wrote the book but after I was probation commissioner. I was on one panel with a guy from The Fortune Society, who was living in a homeless shelter. He was sat next to me, and we were chatting. He was living in a homeless shelter, and he couldn't go home even though his mother had a bedroom for him in her home because his mother had a felony conviction 20 years earlier, and that would have been associating with somebody with a criminal record.

Meek Mill got his case dismissed for popping that wheelie and was sentenced to two to four years by his judge. He only got out because he was wealthy. Robert Kraft, and Jay-Z, and other prominent people advocated for him and got his case thrown out. He'd still be in prison if it wasn't for that.

Brian Lehrer: You write that probation doesn't work for local governments either. You write, "Over 1,000 separate courts assigned supervision of people convicted of misdemeanors to private for-profit probation companies. Hundreds of thousands of people are supervised on privately-run probation annually in the United States." You tell the story of Thomas Barrett, who had to pay for his own probation. Tell us that story.

Vincent Schiraldi: Yes. Thomas Barrett was a pharmacist who became addicted to drugs, lost his job, lost his family, and then he had a drinking problem. When he stole some beer out of a local grocery store, he got put on what's called pay-only probation. This is for people who are too poor to pay a fine, traffic tickets, things like that, and so they get put on probation just to extract the money out of them. Many communities, that probation, you have to pay for that as well. By the time this guy is done, so now, he's literally selling his blood to be able to make the money to pay for his fines and his probation supervision.

This $2 can of beer he steals costs him over $1,000 in fines and fees. When he can't keep up with the payments, he gets stuck in jail for a year. He pays $1,000, does a year of jail time for a $2 can of beer theft.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, we have about five minutes left with Vincent Schiraldi, former Department of Probation commissioner in New York, former Department of Correction commissioner in New York, and now the author of a new book that advocates doing away with probation and parole, you hear the arguments he's making. The book is called Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom. He is currently the secretary of the Department of Juvenile Services in Maryland. If anybody wants to call in with an experience that you had on probation or parole that argues for its abolition, or for that matter, argues for maintaining it, if you want to argue against what Vincent Schiraldi is writing from your experience, we can take a couple of calls in our remaining time. Let's take one right now. Almil, in Brooklyn, you're on WNYC. Thank you for calling in. Hi.

Almil: Honorable Mr. Lehrer, your program is always outstanding, so I thank you for the platform to share. The author, excellent point about probation. I would reference just two books. First, the United States Constitution Amendment 13, with the word "except as punishment for crime." The next book is called Capitalism and Slavery, by the Honorable Dr. Eric Williams. I feel the byproduct, crime, punishment, from 1619 slavery continues. As I'm listening to the author explain, I could only associate those two books as a reference to the larger issue that we are facing. Thank you for your great platform, again.

Brian Lehrer: Almil, thank you for the nice words, and thank you for your call. Here's a question that a listener texted in. Vincent, it says, "Wouldn't taking away the possibility of parole remove an incentive for good behavior by prisoners?"

Vincent Schiraldi: Yes. Just to be clear, I am a little more equivocal in the book than I usually am in real life. Writing a book was really a sobering moment. It's like, "What am I going to say about what should happen?" I say that we should reduce parole and probations numbers, make them more helpful and less punitive. We should even experiment with some abolition and study it very carefully. The two places I say we should experiment is, one, misdemeanors because they get very little help right now, they're the lowest-level offenses. A few places have abolished and it does not seem to have had a negative impact on public safety or outcomes for those people.

I think we should more broadly do that, and I think we should study the heck out of it. The other population on parole, remember, that's the backend, where, in some places, you get out early for behaving better and engaging in programs, but a lot of states have abolished parole release. You don't go before a parole board, you just get out, minus good time. 15% off good behavior, but then you're still on post-release supervision, sometimes called parole supervision. That, I would suggest, is a good place to start because if you did it in those states, they call it a determinate sentence, a flat sentence, then you wouldn't be keeping people longer.

You could still incentivize them with good time, but they wouldn't be supervised after prison. There's actually data that shows, and research by the Urban Institute that shows that people just released do no worse than people who are released on parole. Virginia actually did this for a few years in the mid-'90s. When they had nobody being supervised after they'd come out of prison, crime in Virginia still dropped by 30% during those four years. I'm not saying that proves that we can abolish parole for all people for all time, I just think it suggests that we should take a look at it.

Brian Lehrer: Here's Jeff, in the Bronx, who says he's a parole officer, and I think he's going to push back on some of this. Jeff, you're on WNYC. We appreciate that you called in.

Jeff: Yes, thank you, Brian, for taking my call. I think there's, certainly, the system has its issues and should have been corrected, but this Less Is More now has the parolees with zero responsibility. They're not violated based on one curfew violation, it's multiple curfew violations for convicted criminals who have, for the most part, and oftentimes, committed their crimes at night.

That's why curfews are critically important. Also, you do want to be aware of where a person is as far as crossing the state lines and leaving the state. One of the other issues is if this person has committed their crimes using a vehicle and that there are provisions in their release of them not being able to drive, there are ways in which they can drive for employment and certainly to get home. However, this Less Is More has swung the pendulum so far that a person can have multiple, I'm talking 15 arrests, and still not be violated and still be eligible for what's called the 30 for 30.

That is for every 30 days they're out, they get 30 days off their sentence, which basically cuts their post-release in half. I think that there is still a very critical need, and this Less Is More needs to be reevaluated and redone.

Brian Lehrer: Jeff, thank you very much for sharing your point of view. We've just got a minute left, Vinnie, respond to that and your take on the Less Is More Act, now in effect for the last two years in New York State, which does have less supervision after people are released.

Vincent Schiraldi: Yes, Governor Hochul signed that two years ago when I was commissioner at Rikers. Just interestingly, people who are already in for 30 days on technical violations got released, and Isa Abdul Karim had only been in for 29 days and therefore did not get released and died several days later in Rikers, having contracted COVID-19. There are definitely problems on both sides of this. I think what the state didn't do well, with Less Is More, is it should have captured some of the $800 million it was spending every year on locking up people for non-criminal technical violations, and put them into the kind of services that would help people when they come back to their communities, housing, jobs, education, drug treatment.

Then I would stack that up against technical violations for buying a car when you're not supposed to and staying out past curfew. I don't think there's evidence, and I studied this for several years, that supports that locking people up for curfew violations improves public safety. I know it disrupts people's lives pretty heavily, and it costs a ton of money. I'd like to try something else out, and I think after almost 200 years, probation and parole haven't proved their worth, and they need some disruption.

Brian Lehrer: Vincent Schiraldi, now Secretary of the Department of Juvenile Services in Maryland, is also now author of the book Mass Supervision: Probation, Parole, and the Illusion of Safety and Freedom. Thanks so much for sharing it with us.

Vincent Schiraldi: Thank you very much, Brian.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.