Black Women's Long History Leading American Political Movements

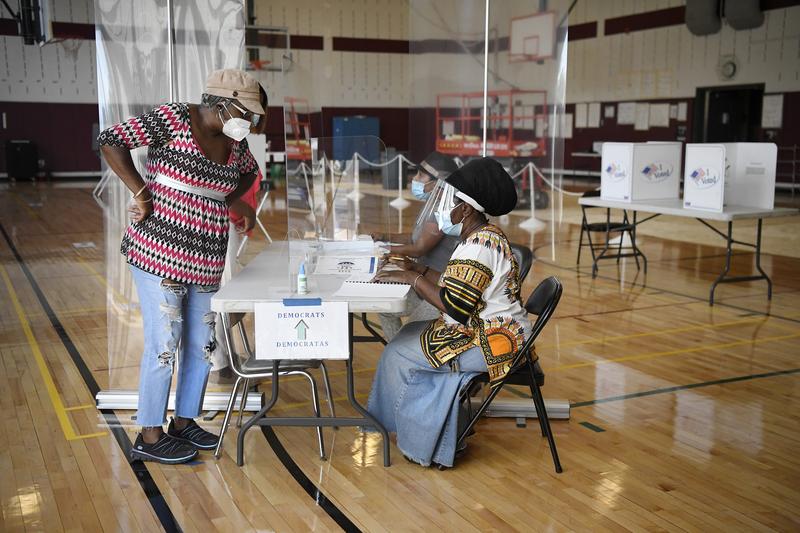

( AP Photo/Jessica Hill )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. Interesting timing on Democratic convention week that yesterday was the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which gave women the right to vote in the United States. Shocking when you first learn American history to realize that that took until 1920 and with Jim Crow and other racial barriers in effect, it really meant mostly that white women could vote starting in 1920. Joining me now is Martha S. Jones, legal and cultural historian at Johns Hopkins and author now of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. Professor Jones, thanks so much for joining us. Congratulations on the book and welcome to WNYC.

Martha Jones: Thank you. Thanks for having me.

Brian: You write about how racism ran through the early suffragette organizations like the National American Woman Suffrage Association and AWSA, which was founded by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who probably for most Americans are the only two names they associate with the women's right to vote movement. How did the National Association of Colored Women and its first president Mary Church Terrell strategically interact with the NAWSA and its founders?

Martha: Mary Church Terrell understands anti-Black racism very well. She's been raised in the American South, but as a suffragist, she both thinks it's important for African-American women to organize independently, to set their own agenda, to steer their own ship when it comes to rights. At the same time, she's an admirer of women like Susan Anthony, who really were path-breakers in their careers. Strategically, Terrell is going to keep, if you will, a couple of fingers in the work of organizations like NAWSA, but the foundation and the center of her political work is going to be in this lesser-known organization, the National Association of Colored Women.

Brian: In the spring of 1913, the National American Woman Suffrage Association planned to march in Washington to demand the right to vote. That's seven years before the final ratification of the 19th Amendment and you write, "In the prospect of Black women participating unsettle the organizers," what were they worried about?

Martha: What the organizer are worried about is that Southern suffragist will refuse to participate in the parade if they're required to march alongside African-American women if they're required to share the spotlight with Black women. Alice Paul, who is the mastermind behind this parade, ultimately fumbles and will require Black women to or attempt to require Black women to march separately. Women like the formidable, Ida B. Wells who will in the end march precisely where she intended to march, which was with the Illinois delegation comprised mostly of white women from Chicago. Alice Paul, if you will, is complicit with and gives in to the white supremacy logic that steers white suffragist and minimizes and marginalizes African-American women on that historic occasion.

Brian: You mentioned Ida B. Wells so I noticed you also give credit to in your books, acknowledgments. She's, for people that don't know, one of the founders of the NAACP, an investigative journalist, led anti-lynching campaigns in the US as early as the 1890s. Why does she loom so large over your work?

Martha: Wells really exemplifies Black women's style in politics by the end of the 19th century. As you described, she's never a one-issue activist. She really comes to national repute as the chief advocate of anti-lynching legislation, but she is also a suffragist founder of the NAACP and much more. I really admire Wells because she is in her own way profoundly audacious, which is to say she is not someone who minces words, she's not someone who lets folks off the hook and in fact, leaves a record for us that for a very long time, was our only documentary record of scourge of lynching in the United States.

She was even a pseudo-social scientist in her approach to her activism. She learned how to work with white women but her home, as was true for Mary Church Terrell, were in the clubs, were in the suffrage organizations led by African-American women.

Brian: You open your book with a story of your own matriarchs starting with, "Nancy Bell Graves, who was born into slavery in 1808," you write and who, "had kept the homes, cradled the children and laundered the dirty linens of white Americans. People who thought that she and her daughters were worth little more than meager shelter or paltry wages. Steely raped by 1920, Nancy's daughters were women of learning status and enough savvy to navigate the maze that led to the ballot box." That's an amazing family history. When did you learn about it with respect to voting?

Martha: I was finishing Vanguard and I write in an office with the photographs of these women, including my own grandmother, Susie Jones on the wall, and someone who thinks of myself as accountable to those women when I write my histories. I became self-conscious and even a little bit embarrassed because I realized I didn't know the story of their attempt, their efforts. They're getting to the ballot box. Finally, these women who were the descendants of enslaved people, some of them have been enslaved themselves.

I start on a journey that takes me to St. Louis in Missouri, Danville in Kentucky, and finally to Greensboro in North Carolina, which is where my grandmother, Susie Jones, along with her husband, David had moved in 1926 to begin a college for African-American women and a college, which is still there today. I went to the archives in North Carolina in Raleigh thinking I would find her somewhere on the rolls, only to discover that those records hadn't been kept. That the state of North Carolina has not valued those quotidian documents that would tell us who voted when and how after the 19th Amendment.

I had to continue and pull the thread. I was lucky to happen on an interview that she gave in 1978 with historian Will Chafe at Duke University. She lived in Greensboro and Chafe was interested in the civil rights movement and the [unintelligible 00:07:46] in the city of Greensboro. The story my grandmother told was about the '50s and '60s and the ways in which Bennett students had gone into the Black community in Greensboro and registered folks and gotten them to the polls in those very troubled, very dangerous years before passage of the Voting Rights Act.

It was a lesson to me, Brian, in the way when we take the perspective of Black women and we want to write the history of voting rights, we can't stop in 1920 at all because for my grandmother, 1920 is a story I'll never know. Her real triumph, if you will, and as she put it, she was thrilled when in 1950 and 1960 and the modern civil rights era, now African-American women are part of that decisive push that brings Black Americans finally to the polls. I couldn't end my book in 1920 at all. I had to bring it all the way to 1965.

Brian: We're going to do that too in a way that I hope you'll appreciate and our listeners will appreciate in a minute when we come back from a break. I pulled a classic clip of Fannie Lou Hamer. Since this is convention week from the 1964 Democratic convention that relates to everything you're talking about and I'm going to play that clip, but also listeners I want to invite anybody who might be listening, African-Americans who might be listening, who might have a story from your own family like the one Martha S. Jones just told from hers.

If you're just joining us, our guest is Johns Hopkins historian, Martha Jones, and her new book is called Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. On this day, 100 years and 1 day after the ratification of the 19th Amendment, which really didn't apply to Black women at that time. Does anybody listening have a story like this from your own? Again, just to repeat the subtitle of the book, How Black Women

Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. Anybody have a Black woman's suffrage story from your own family, maybe a little bit like the one Martha Jones just told from hers, just in case. If any of you're out there with a story like that, we would love to hear it. 646-435-7280. 646-435-7280. We'll continue with Dr. Jones and that Fannie Lou Hamer clip right after this.

[music]

Brian Lehrer on WNYC. As we continue with Johns Hopkins historian, Martha S. Jones, author now of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. I pulled a two and a half minute clip from the 1964 Democratic convention of Fannie Lou Hamer, who you write about as a civil rights activist, obviously, including a voting rights activist centrally. She also ran in a Democratic primary for Congress that year, for listeners who don't know that.

Even in the context of today's shocking times, the story she tells here is truly extreme by today's sensibilities. This is from an era when conventions had much more suspense about how things would turn out. There was no suspense that year about Lyndon Johnson being the nominee, that was a foregone conclusion. In this clip, Fannie Lou Hamer is addressing the Credentials Committee of the Democratic convention, looking for recognition of delegates from what they called the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which was different from the pro-segregation Democrats who led Mississippi at that time. This is the first two and a half minutes of her presentation.

Fannie Lou Hamer: Mr. Chairman, and to the Credentials Committee. My name is Mrs. Fannie Lou Hamer, and I live at 626 East Lafayette Street, Ruleville, Mississippi, Sunflower County, the home of Senator James O. Eastland, and Senator Stennis. It was the 31st of August in 1962 that 18 of us traveled 26 miles to the county courthouse in Indianola to try to register to become first-class citizens.

We was met in Indianola by policemen, Highway Patrolmen, and they only allowed two of us in to take the literacy test at the time. After we had taken this test and started back to Ruleville, we was held up by the City Police and the State Highway Patrolmen and carried back to Indianola where the bus driver was charged that day with driving a bus the wrong color.

After we paid the fine among us, we continued on to Ruleville, and Reverend Jeff Sunny carried me 4 miles in the rural area where I had worked as a timekeeper and sharecropper for 18 years. I was met there by my children, who told me that the plantation owner was angry because I had gone down to try to register. After they told me, my husband came and said the plantation owner was raising Cain because I had tried to register.

Before he quit talking the plantation owner came and said, "Fannie Lou, do you know-- Did Pap tell you what I said?" And I said, "Yes, sir." He said, "Well, I mean that." He said, "If you don't go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave." Said, "Then if you go down and withdraw," said, "you still might have to go because we are not ready for that in Mississippi." And I addressed him and told him and said, "I didn't try to register for you. I tried to register for myself." I had to leave that same night.

Brian: Fannie Lou Hamer at the 1964 Democratic convention. Her statement goes on for another six minutes. If you think what you heard there was bad, her story gets much worse, including being arrested and being savagely beaten by multiple people. You can find the whole thing online later if you want to hear the whole thing, but Martha Jones, where would you say that Democratic convention fits into the big sweep of history in your book and, of course, that Fannie Lou Hamer presentation?

Martha: Fannie Lou Hamer makes plain as she speaks on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party that delegates from the state of Mississippi who have been seated at that convention without the ascent, without the vote, without the consultation of Black Mississippians are not legitimate delegates. That American democracy will no longer tolerate the notion that voting rights are realized when Black Americans like Hamer and thousands upon thousands of others continue to be kept from the polls in a state like Mississippi, as we heard by intimidation and violence along with literacy tests.

Fannie Lou Hamer states the claim on national television and so unsettling that Lyndon Johnson will step to the podium and preempt her live on television in an attempt to suppress her remarks but of course before the evening is over, the network will, in fact, play her remarks and we have them now to help us appreciate how vexed a struggle Fannie Lou Hamer and the many other heroines of the civil rights movement, how vexed their circumstances were.

Brian: Lyndon Johnson stepped in to interrupt the remarks that we were just listening to?

Martha: He did. He came on live television because Hamer was calling into question the very legitimacy of that convention that was going to, of course then, nominate Lyndon Johnson as their candidate. Hamer said, "Delegates who are here that haven't been elected by all people, by all Americans, by all Mississippians, are not true delegates and should not be seated." She looks to have the Black Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party delegations seated in their place.

Brian: What happened?

Martha: She doesn't succeed and we know that, of course, that Hamer will spend an extraordinary amount of time in the back room. She will be implored by party activists, including figures like Martin King to step down and to compromise. Perhaps you can hear it Fannie Lou Hamer's voice, she had not come to the Democratic convention to compromise and she will go home without her delegation having been seated, but she will have gone home after making this remarkable record that we hear the delegitimation of a national party convention and her struggle, of course, for voting rights will continue back in Mississippi where there is a tremendous amount of work to do on the ground.

Brian: An example there in 1964 of continuing to try to get the right to vote in real terms for Black women as well as Black men that long after the 19th Amendment was ratified in 1920.

Martha: Yes. Here we are almost 45 years after 1920 and Black American women like Hamer are doing the work that had been started by Black women way back in August of 1920. What they are seeking is federal legislation that will give teeth to the 15th Amendment that had been ratified in 1870, the 19th Amendment that had been ratified in 1920, but that were still supported by state level, Jim Crow laws along with violence. This is the work of the voting rights movement that begins in 1920 and takes us all the way to the Voting Rights Act signed by Lyndon Johnson in 1965.

Brian: We have a few minutes left with Johns Hopkins historian, Martha Jones author now of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. I want to spend our last few minutes bringing it up to the present. Senator Kamala Harris has achieved a lot of firsts. She was elected as the first African-American and first woman to serve as California's attorney general, as you know, as most of our listeners know. The first African-American to represent California in the United States Senate and the first South Asian-American senator in history and yet when she's asked about her first, she often responds with a quote from her mom, "You may be the first to do many things, but make sure you're not the last." What do you make of that response?

Martha: I'm someone who thinks it's time to dispense with the honorific of the first. With all respect to Senator Harris and her achievements, she represents to my mind a force. The force that begins in an important degree with figures like Fannie Lou Hamer. Today, Senator Harris was not the single contender, the single woman of color, the single Black woman contender for the VP slot. In fact, there were six Black women because Black women have spent generations since 1920 preparing themselves, positioning themselves for this national leadership. Kamala Harris will run in November alongside more than 120 Black women who are vying for seats in Congress this year. These are not first anymore. These are women who represent a true force in American politics.

Brian: I notice that in The Washington Post appeared that you wrote the other day, you noted that that number 120, 130 Black, or multiracial women seeking seats in the US House and Senate this November. You contrasted with 2012 not that long ago when only 48 Black women ran. It's like triple.

Martha: Yes, and that's why I think the term "Force" is apt. That each generation but even in these quick successions of election cycles, what we're seeing are the ways in which Black women who have long been mayors, city council members, in state legislatures are now coming to national prominence and vying for national office. These are women who are connected with, for example, the 98% of Black women who voted in 2017 for Doug Jones in Alabama and flipped that Senate seat from red to blue in that Southern state. The 96% of Black women who voted for Hillary Clinton. These are parts of a whole story about the ways in which despite having to wait until 1965 to fully win voting rights. African-American women have made themselves real contenders for political power here in 2020.

Brian: I imagine that your book was completed and was gone to press before the police killing of George Floyd in May and the current burst of protest activity that's been going on ever since. If you could add an addendum to the book based on the last few months, would you?

Martha: I think I'd have to. There's no question but the intersection, if you will, of the coronavirus and the uprisings in response to the continued police killings of Black Americans has only sharpened the urgency that undergirds the role that Black women will play in November. Voting rights were already, if you will, facing a challenge going into this election now as was true frankly in 1920 when Black Americans had just faced Klan violence. If they dared go to the polls today in 2020, Black Americans are being asked to face the scourge of the coronavirus in order to cast ballots. For me, I think that parallel is too powerful to have passed up on. I appreciate the opening to make that point here.

Brian: With that, we will leave it with Martha S. Jones, legal and cultural historian at Johns Hopkins University and author of Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All. Let me tell you about a couple of virtual book events that she has coming up on August 26 is one of them. That's next week at 6:00 PM Eastern. She will join the National Archives in conversation about the book to mark the ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Let's see. Let me do the math. What's today? The 19th and seven. That's a week from today, Wednesday, August 26 at 6:00 PM. That's at archives.gov and on the books official publication date which will be Tuesday, September 8 at 7:00 PM Eastern. The Harvard Book Store will be hosting a virtual talk with Martha and a special guest. Both virtual events are free with RSVP online to the National Archives for August 26 and the Harvard Book Store for September 8th. Thank you so much for this history and for sharing it with us today.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.