Biden's Winter COVID Plan

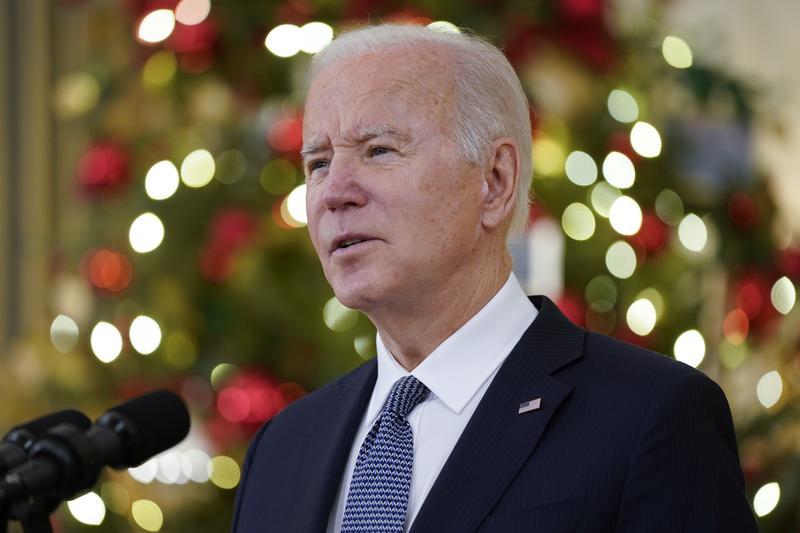

( Evan Vucci / AP Photo )

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Good morning, everyone. We have good news from the weekend about COVID-19, bad news about COVID-19, and news that will make most of you who listen to this show want to call up that certain person in your life and say, "I told you so. Now wake the blank up." The good news comes from Dr. Fauci as the Omicron variant spreads in the United States.

Dr. Fauci: Thus far, it does not look like there's a great degree of severity to it, but we really got to be careful before we make any determinations that it is less severe or it really doesn't cause any severe illness comparable to Delta. Thus far, the signals are a bit encouraging regarding the severity, but again, you got a whole judgment until we get more experience.

Brian Lehrer: Dr. Fauci on CNN State of the Union yesterday. That's the good news, very preliminary about the severity of Omicron, but at least an encouraging start to evaluating it. Here's some of the bad news. Reports from South Africa say the number of children being hospitalized with COVID there since Omicron broke out seems to have taken a sharp increase from before. In this country, the directors of the Center for Disease Control, Dr. Rochelle Walensky, went on the Sunday morning show ABC This Week yesterday to say don't get too focused yet on Omicron at all.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky: The first thing I think we should say is that we have about 90,000 to 100,000 cases a day right now in the United States, and 99.9% of them are the Delta variants.

Brian Lehrer: 99.9% of them are the Delta variants. That's the bad news. Delta is still dominant, the numbers are going the wrong way in this country, and Omicron severity in children is an open question, at least, based on the early data from South Africa. Now, here's the news that will make many of you want to call up that certain someone in your life and say, "I told you so. Now wake the blank up."

A survey by NPR finds people are almost three times more likely to die from COVID if they live in counties that voted for Donald Trump last year than that voted for Joe Biden. Reminds me of the story we mentioned last week about the six anti-vax talk show hosts in this country who have died from COVID since last summer, six if you count one televangelist among them.

There aren't that many talk show hosts in the whole country, so six is a lot. That includes the televangelists, Marcus Lamb, who died just last week, founder of the Texas-based Daystar Television, who had publicly shunned the vaccine even though he had diabetes. He had the huge risk factor for serious COVID of diabetes, and didn't get the vaccine, and railed publicly against it.

The Newsweek story I read about that said he did take Ivermectin earlier this year to help prevent COVID, Ivermectin instead of vaccine, so listeners beware of fake medicine and beware of fake news. By the way, Marcus Lamb was based in Texas, and the Houston Chronicle reported last week. I haven't seen others put this together, but maybe we should. The Houston Chronicle reported last week that more than half the people who have died from COVID in Houston, 52% of the people who have died from COVID in Houston through the whole pandemic had the same underlying condition; diabetes.

Diabetes is a risk factor and so apparently is being an anti-vax talk show host, and so apparently is living in a Trump-voting county. The NPR story on this says people living in counties that went 60% or higher for Trump had 2.7 times the death rates of those that went for Biden. It's a curve. It's not just a binary, which gives it an even stronger statistical foundation.

Counties with an even higher share of the vote for Trump saw even higher COVID-19 mortality rates, and so comes the question, what's the best policy response by Joe Biden this winter to save the lives of people who disproportionately did not vote for him who are disproportionately at risk, as well as, of course, those who did vote for him as we're seeing those numbers go up with the change of seasons in all groups, and amid the nursing shortage that we talked about on Friday, and with the increasing importance of rapid tests, which so far are too expensive for that many people to take very often.

With me now, Dylan Scott, who covers healthcare and other domestic policy for Vox. Among his major projects at Vox have been one-on countries that excelled at their Coronavirus response, and another on how different countries achieve universal healthcare access. His story published on Friday is called Biden's Winter COVID Plan is What a New Normal Might Look Like. Dylan, thanks for coming on. Welcome to WNYC.

Dylan Scott: Thanks for having me.

Brian Lehrer: Let's start with the clips we played from Dr. Fauci and Dr. Walensky. Interesting that so far the Omicron variant seems milder than Delta, though still very few cases to base that on. Do you have anything to add to an early assessment of Omicron based on the indicators you've been watching as a health reporter?

Dylan Scott: No. I think that seems to be the consensus for now. Certainly, as everybody keeps cautioning, including Dr. Fauci in that clip, it's going to take more time for the data to come in, for the statistical analysis to be run, for us to really have a good idea on all of these big questions; how severe of a disease does it cause, how well do the vaccines hold up against it, how transmissible is it? That's just going to take time.

I know from some of the conversations I've had with scientists, there's a fair amount of optimism that the vaccines will hold up well, particularly if people end up getting booster shots. Other than that, it's all very preliminary. Obviously, South Africa has become the focal point because they're great at genetic sequencing. They're really good about data collection and distribution, and so they are giving us an early picture of what Omicron might do.

It's also very different, especially from a country like the United States, in important ways where even as much as we've struggled to some degree with our vaccination campaign, South Africa has about half as many people vaccinated as we do, at least as a share of their population. I know some folks I've talked to said they're going to watch what happens with hospitalizations in Israel, which might be a slightly more comparable-- a better comp to the US because they tend to follow the playbook on COVID, and they are likewise very good about sequencing samples of the virus and reporting data in a timely fashion.

To Dr. Walensky's point, we'll certainly be watching to see whether or not Omicron starts to make up a bigger share of cases in the United States because that's really the ultimate question, is does it have the kind of wherewithal to outcompete Delta? That is something we certainly don't know. It will depend on some of the answers to these questions about severity and transmissibility, and how it interacts with the vaccines. That's just going to be an open question for the time being.

We've had other variants come and go that people have probably already forgotten about that initially seemed like they might be cause for concern and ultimately fizzled out. I think there's good reasons to think Omicron poses more of a threat to Delta in terms of its ability to become the dominant variant across the world, but it's just going to take time, which I know is a maddeningly imprecise answer, but we're just stuck in this limbo period for the time being.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Just to be clear, when you say South Africa and Israel are good at genetic sequencing, what that means is they do a lot of testing to see which variant positive people have, so they have a pretty good handle on what's Omicron, what's Delta, what's something else. Now, one eye-popping stat that I saw about its transmissibility is that the number of cases of COVID at all diagnosed in South Africa went up tenfold in the last few weeks. Did you see that one?

Dylan Scott: I've seen the curves coming out of South Africa. There's been a dramatic spike in the number of daily cases since the beginning of November, which coincides with Omicron being identified and appearing to get a foothold in the country. That's certainly one of the most worrying signs that we've seen as far is just the sheer rise in the number of cases in South Africa.

Brian Lehrer: Did you see the troubling reports about severity in children there because it seems to me that what we heard from Dr. Fauci and most of what we're hearing about the individual cases in this country so far are that the Omicron variant cases are relatively mild, but then we have this thing in the other direction that there's a spike in the number of children being hospitalized with pretty severe cases in South Africa.

Dylan Scott: Yes, I hadn't seen that same data. It does seem like cause for concern. It's one of those things where they're not mutually exclusive. I'm not positive off the top of my head what South Africa's policy towards vaccinations with children or what percentage of children are vaccinated in that country, but here in the United States, certainly the majority of our children, even those who are eligible are not vaccinated. I would imagine it's probably the same there as well. It may be that both things are true at once, that it's certainly especially with vaccinations, Omicron can be-- the severity of the disease can be pretty well blunted, but if we don't do a better job of vaccinating kids, they're going to remain vulnerable to this variant that in the wild, with a naive population, people who don't have any protection against COVID of any kind, it could end up being at least somewhat more virulent. That certainly poses a risk to the unvaccinated populations, a large percentage of whom are children. I think those two things almost work in tandem if that makes sense.

Brian Lehrer: We'll talk about your coverage of Biden's COVID policy response for this winter, but before we even get to that, I want to share some breaking news about COVID policy response here in New York City. This just came out before the show. I don't know if you've seen it yet. I'm just going to read from the New York Times version, which just broke a few minutes ago.

Headline, New York City sets sweeping vaccine mandate for all private employers. That's the headline. Then the body of the article says, "Mayor Bill de Blasio announced a sweeping coronavirus vaccine mandate for all private employers in New York City on Monday morning to combat the spread of the Omicron variant. Mr. de Blasio said the aggressive measure, which takes effect December 27th and which he described as the first of its kind in the nation was needed as a 'preemptive strike' to stall another wave of coronavirus cases and help reduce transmission during the winter months and holiday gatherings. "

That's about all I have on that so far. All private employers, I don't know if that includes small businesses in brick and mortar stores or whatever of just a couple of people, but all private businesses, vaccine mandate, is this the first you're hearing of it?

Dylan Scott: I had just seen it before we hopped on, but otherwise I don't know a ton of extra detail. I think it's worth remembering and it doesn't surprise me necessarily that we'd start to see some cities do this, especially because the policy that the Biden administration issued I think at the beginning of November trying to institute the same kind of mandate nationwide has gotten tied up in the courts. I actually think that the Biden example is instructive because whether-- I'm not a lawyer.

Brian Lehrer: The Biden or the de Blasio?

Dylan Scott: The Biden example because I think it's instructive for what may happen and why Mayor de Blasio may be going ahead with this because I won't pretend to be a lawyer about the legal permissibility of the government requiring employers to require their employees to get vaccines, but what we saw after the Biden administration made its announcement was a lot more companies did institute a mandate even though it was clear from the start that this was a legal open-ended question and the Biden policy might not ultimately stand up in the courts. We saw, as a result of those companies instituting their own mandates, that there was a dramatic uptick in daily vaccinations and particularly new vaccinations, first doses for people throughout the month of November.

I think that was maybe a lesson in that sending the signal of we are requiring mandates both gives companies the cover to institute that policy on their own, and once those policies are instituted at the company level, most people don't want to lose their jobs and don't want to leave their jobs over something like a vaccination. It can have the desired effect in terms of increasing the number of new vaccinations whether or not it ultimately stands up in the court.

I won't pretend to know If somebody is going to challenge what Mayor de Blasio has instituted or whether it would hold up in courts, but I think we have a pretty good and recent lesson from the Biden policy that suggests it can still have a positive effect on vaccinations regardless of how the legal arguments play out.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. We'll see if this sets a precedent for other localities since this does seem to be the first of its kind in the nation requiring all private employers in the city to have vaccine mandates. It's not clear to me yet, from this very early reporting, whether that just applies to employees or whether that also applies to customers coming into stores, I assume it's for the workers.

The time says the Mayor also announced that the rules for dining and entertainment would apply to children ages 5 to 11, who must have one dose to enter restaurants and theaters starting on December 14th, the children were not required previously, and that the requirements for adults would increase from one dose of vaccine to two starting on December 27th.

There's that breaking news, folks, from New York City today, perhaps a template for the nation, at least starting a new conversation in New York. I guess for New Yorkers, we should remember the context that Mayor de Blasio, who leaves office this month at the end of this month, is likely to run for governor and he is now gone further than the sitting governor, Kathy Hochul, who's very pro-vaccine and pro-vaccine mandate, but she hasn't gone this far. I guess de Blasio was trying to establish himself as a leader, the leader, on this.

We'll also see, New Yorkers, what happens with Eric Adams when he becomes Mayor on New Year's Day. They reached him the time stated for an early comment, and all he said was, "It's new. I have to evaluate this." Interesting politically, Dylan, since you cover politics as well as healthcare, that in the New York City context, Mayor de Blasio may make this decree on December 6th, but it's not necessarily going to last past January 1st because it's not up to him.

Dylan Scott: Right, exactly. You know better than I do in terms of how the interactions between the outgoing and incoming administration in New York City, but, yes, it seems like the kind of thing he wanted to lay down a marker. I could imagine that once that policy is put into place, even if it is put into place in the final days of his term, it would be politically difficult to try to roll it back, especially in a city like New York that had the experience with COVID that you all did, especially early on. I have to imagine that that policy will have a lot of purchase with people in New York City.

It seems like the thing where, yes, technically speaking, maybe incoming Mayor Adams could roll it back if he wanted to for whatever reason. Once a policy like that gets put into place, it suddenly becomes a story if you try to undo it. I have to imagine, especially in the first couple of weeks or months of his administration, Mayor Adams may not want to be trying to make the case to the public about why he's rolling back vaccine mandates, especially if we have a winter surge or if Omicron does become dominant. I think that would only strengthen the case for the policy Mayor de Blasio is putting into place.

Brian Lehrer: Yes, good point. Listeners, we're talking about COVID news with Dylan Scott who covers healthcare and other policy for Vox. Our phones and Twitter feed are open for your questions or observations about what de Blasio just announced this morning. You can react to that. Maybe some business owners want to call in. If you have not imposed a vaccine mandate for yourself and your workers yet, or about the early information about Omicron, the much more serious threats so far and still rising of the Delta variant, or that person in your life, or maybe that's you, who is a vaccine rejectionist as a political identity, despite the galaxies of data, like the new NPR survey we mentioned at the beginning,

we'll get back to it and talk about it a little bit, that finds the more your county voted for Donald Trump, the higher the COVID death rate in that county or anything else related at 212433 WNYC 2124339692.

Dylan, I want to go to one part of the Biden response that you wrote about that I think is really important to talk about, and that is rapid tests, their increasing role in pandemic response as opposed to PCR tests, and why Biden's announcement about rapid tests and insurance last week is unsatisfying to many experts. Can you talk about that?

Dylan Scott: Sure. Yes, as you say, a key piece of the Biden plan is they're going to issue new regulations and guidance that basically give people permission like if you order a rapid test off of Amazon or go buy it at CVS that you would be able to submit that bill to your health insurer to receive reimbursement. The idea is to make tests free ultimately to people because tests are such an important part of any kind of pandemic response and tracking. We want people to be taking tests proactively, especially if they have any reasons to think that they might've been exposed to COVID so that they know whether or not they should be isolating themselves or taking extra precautions.

There's been a lot of work done to make these rapid tests both more reliable and more widely available. We're reaching a point where COVID is here with us to stay, and so rapid at-home testing may just become a normal part of life to some degree anyway. One thing that we know about healthcare in the United States is that any kind of cost barrier inevitably discourages people from using a healthcare service. We know since early this year, insurers have been allowed again to require their customers to pay some of the costs of their COVID testing which was a change from last year, and really the heat of the public health emergency.

The government had mandated that insurers cover tests for free. That had started to change over the course of this year, but now as we're approaching the winter and with the specter of Omicron hanging over us, the Biden administration wants to try to make tests free for people again. The way they are proposing to do it is this insurance reimbursement, where you buy the test yourself and pay money out of pocket yourself to get the test but then once you've done that you can send the bill to your insurer.

The idea is they'll reimburse you for that cost. Now, the issue that some experts take with that plan is the idea that you're going to require people to buy the test themselves at the point of sale; at the pharmacy or through Amazon or what have you. That's for the reason that I already stated that if there's any kind of cost barrier people might just not do it.

Even if they know they can get reimbursed for the test from their insurer, they might be like, "I don't have the $25 to spare for this test kit right now," and then on top of that, you could have a situation where, yes, somebody buys the test, but they ultimately don't submit the bill for reimbursement.

It's called the shoebox effects, which was actually something that I learned about in reporting this story, the idea that there's been other examples throughout health policy in the United States of where we were asking patients to pay for their service themselves and then submit the bill for reimbursement to their insurers. What ends up happening is people just throw those bills in a shoebox and forget about them and they never end up getting reimbursed at all.

The problem that experts have with this is if the goal is to make testing free and to encourage people to use testing as much as possible, wouldn't it be much easier to actually provide the test to people for free from the start, rather than asking them to go through this rigmarole of getting it reimbursed by their insurer. The Biden administration, I think, is cognizant of this and trying to balance between, first of all, it would require a lot of money for the federal government to buy enough tests for everybody.

Just like for some loose back of the napkin math, a testing kit for the Abbot rapid at-home test costs about $25 at CVS. If you wanted to provide even just one test for everybody in the United States or one testing kit for everybody in the United States, you're already talking about billions of dollars in costs and so that we- [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: Then if we're talking about these tests being used on a very regular basis, like every time you're going into an in-person interaction with a group, or some people talk about it as a regular thing before going to work, imagine 350 million Americans times $25 times how many days, right?

Dylan Scott: Yes, exactly. It becomes pretty untenable funding-wise pretty quickly, or at least the Biden administration, it's hard for them to imagine going to Congress, as contentious as everything is up there on Capitol Hill, going to Congress and asking for billions upon billions of dollars for COVID testing. From the government's perspective, it's certainly easier to just issue some regulations that allow people to submit their own bills to their health insurer to get paid but you have this trade-off of maybe that means some people don't buy a test, or if they do buy a test, they don't ultimately get reimbursed. That creates obstacles to people getting tested in the first place.

Brian Lehrer: It also reinforces some of the savage disparities in the COVID pandemic so far. I saw your new article this morning on who the pandemic's next phase is likely to hurt the most, and spoiler alert, it's still lower income people of color who have less access to health insurance as the first risk factor that you mentioned.

Dylan Scott: Exactly. Yes, this only serves to deepen disparities. It might not be that big of a deal for me or you to go on Amazon or go to CVS and buy a $25 testing kit but there are a lot of people for whom that is a big deal. Now, the only guarantee they have that they're actually going to end up getting that test for free is if they go through this reimbursement process, which is just a hassle for people who maybe don't have the time to do that kind of thing. There are parts of the Biden plan that try to offer free testing through community health centers and through rural health clinics. They're certainly trying to address that.

They're, in general, I think trying to strike this balance between responding to everybody. Most experts I have spoken with and read anticipated some surge over the winter in cases, and we'll see how much Omicron might exacerbate that. They're trying to balance between being prepared for the next couple of months, but also taking an even longer view of like eventually nobody believes that we're going eradicate COVID at this point, it's going to be something that we're going to have to live with.

We will eventually have to transition to a world where COVID testing and COVID treatment and all of it is a more conventional medical service. I know that's something that the Biden White House has in mind. I think the debate among experts is like, is now the time to be asking people to buy a COVID test and submit it for reimbursement from their insurer when we've got Omicron looming over us and we're already worrying about a winter surge? I think in the eyes of some of these experts, it would be money well-spent to provide tests to people for free, to get through the worst of this for these next couple of months, and then eventually we can figure out, all right, how are we going to treat this stuff more normally?

Brian Lehrer: Longer-term policy.

Dylan Scott: Exactly.

Brian Lehrer: We'll continue in a minute with Dylan Scott from Vox. We'll get into that NPR finding that the more likely your county was to vote for Donald Trump, the more likely you are to get COVID and die from it. We'll take some of your phone calls and a little more on the new normal aspect of this that Dylan wrote about in Vox. Brian Lehrer on WNYC stay with us.

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC as we talk about all kinds of COVID news with Dylan Scott who covers healthcare and other policy for Vox. We're going to go to some of your calls here and tweets. I'm going to start with a tweet, Dylan, from listener Yellow Chick who writes, "Vox reporter on Brian Lehrer Show saying it's too expensive to send everyone rapid tests, but neglects to say that the markup is enormous," and she asks, "In the UK?"

What about that? If we're talking about $25 at the pharmacy for a two-pack of rapid tests the one from Abbot as the example, you and a lot of people use, what about the markup? Could Abbot be forced to eat some of that? As someone who has reported on other countries that do health insurance well, do you know about other countries handling this, UK or anyone else?

Dylan Scott: Yes, no, it's a totally fair question. I certainly have had it in mind as I've been writing about this that I use the retail price just because it's the best reference point that we've got, but certainly you could imagine that if the United States government said the only way you're able to sell and distribute these tests is to go through us and we'll send them out to everybody that they'd be able to negotiate a better price.

I don't know precisely what the markup is, but even so, and nobody likes that this is the way that it works, but even if you come at that price in half or more down to, let's say, $10 per testing kit, now you're still talking about what? Like $3.5 billion to send it out to everybody in the United States. As you pointed out, if the idea is to use these tests routinely every day, maybe not every day, but on a regular basis, then that price tag only increase manifold.

Unfortunately because of the way the federal government works, HHS does have some ability to do some creative accounting and find funding where they might want to find it but once you're talking about dollar figures in the billions of dollars, which I think we would be even at an extreme markup, Congress has to sign off on it. Congress has to appropriate the funding in order for the administration to be able to do that.

That seems to be where the White House is thinking, "With everything else we've got going on right now and with all the money for COVID response that we've already asked for, asking for the money to provide free testing to everybody is a bridge too far." I think it's perfectly debatable whether or not that's true, and certainly, some of these experts that I've talked to think that the cost would be worth it, but that is their thinking based on some of the conversations that I've had. The other question-- Oh, excuse me, Brian, I just-

Brian Lehrer: No, no, go ahead. I guess you're going to go right where I was going to go to whether Abbot or other companies can be mandated to take less profit.

Dylan Scott: Oh, that was not where I was going to go, but I do think in this situation, and, yes, there's like a procurement process where if the federal government were acquiring the test themselves to distribute them then there is a procurement process that would allow the government to set a lower price than what Abbot might be charging it CVS or on Amazon. In terms of the government's ability to regulate normal commercial transactions, like somebody buying it through CVS, I don't know that the government has much-- At a certain point, the market is the market. As long as we're doing it this way where people buy tests on their own and then go to their insurer to get reimbursed, I don't know that the government has a lot of leverage to try to get Abbott to lower their price.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe through their buying power. Jeff in Derry, New Hampshire, you're on WNYC. Hi, Jeff. Thanks for calling in.

Jeff: Thanks for taking my call. I've got a couple of personal experiences and an opinion and a question. One is, one of my uncles died in October of COVID having not been vaccinated [unintelligible 00:30:43] people in my extended family. He did live in a very Republican pro-Trump part of Tennessee, [inaudible 00:30:49] New York. Since then the few remaining [unintelligible 00:30:55] in my family has woken up and been vaccinated. That's great. I'm thrilled with de Blasio's decision partially because I'm a gay man and I lived through the AIDS epidemic in the '80s. In the '80s, [unintelligible 00:31:09] government support at first and watching a friend of a friend die, sometimes while I was holding his hand.

I knew of the served Republicans in this country, including the Texas legislature, that at one point, voted over 40% in favor of a law that would put all gay men, not even with AIDs, all gay men in concentration camps to stop the spread of AIDS. Yes, those people were so adamant about a non-airborne disease to say, "Let's round them all up and put them in concentration camps like Nazi Germany." Then the idea of the government mandating that unless you have a very specific medical problem that you must be vaccinated, to me, is not the least bit a stretch of the imagination. I think legally it can be eventually worked out hopefully.

I would be very much [unintelligible 00:31:59] because I personally believe that thousands of people are dying, including my uncle because of these leaders that you mentioned earlier, Brian, the talk show hosts [crosstalk] if they're still alive, should be charged with manslaughter as well as any political leader, like some of the nut jobs in Congress, because this is manslaughter. This is perceptively encouraging people to take out just the means that thousands of people would otherwise not die are dying. I'm sick and tired of this ridiculous US freedom, choice, blah, blah, blah, that's going on. I would like you and your guest's and anybody else's opinion about what I believe is what exactly what de Blasio is doing, I'm thrilled, should happen all over the country immediately as soon as possible.

Brian Lehrer: Thank you, Jeff. I'll also add that when you bring up the reliance on freedom to control what happens to our own bodies, argument, very prominent in Texas, as you use that state as an example, then look at what they're doing with the abortion law. We're going to talk about that later in the show, what happened to freedom of control over your own body. For those of you just joining us, there is breaking news about a new de Blasio policy for New York City that Jeff was referring to there, de Blasio announcing this morning, a vaccine mandate for private employers in the city to take effect December 27th. Apparently, all private employers in New York City will have to get their workers vaccinated in order to allow them to their worksites by December 27th.

He also added a vaccine mandate for children, 5 to 11, which didn't exist before, if they're going into restaurants or theaters or other entertainment venues that had only applied to older people previously. Starting on December 14th in New York City, kids ages 5 to 11 will need to show proof of vaccine, not to go to school, de Blasio doesn't want that, he doesn't want a barrier to going to school in person, but to go to a restaurant, to go to a theater, another entertainment venue, even kids as young as five. Divine in the Bronx, you're on WNYC. Hi, Devon. Thanks for calling in today.

Divine: That's me. Hi, how are you doing? I was hoping you can help me understand the numbers because they say COVID affects the most people of color, but you just said that more people that voted for Trump died. How do I understand those numbers?

Brian Lehrer: You anticipated my very next question to Dylan Scott from Vox. How would you respond to Divine there who put in context the NPR findings that the more Trump-voting a county that you live in, the more likely you are to die of COVID so far in the pandemic when at the same time we know that it disproportionately has been killing low-income people of color who are the least likely to vote for Trump.

Dylan Scott: Sure. It's a fair question. I think it's a difference between raw numbers and proportions. This is still a country that's 75% white, so there just are a lot more white people out there. That is where that provides the basis for the NPR finding that people who lived in Trump-leaning counties, which tend to be more likely to be white, have seen the highest number of deaths going forward. Generally speaking, most people who have died from COVID have been white, but that's because three-fourths of the country is white. If you compared as a percentage how many white people have gotten sick with COVID or been hospitalized with COVID or died from COVID versus what percentage of Black or Hispanic or American Indian people have gotten COVID been hospitalized with COVID or died from COVID, the share for the latter group, some of our ethnic minorities, are higher than it is for white Americans.

That is the difference, as a matter of sheer numbers, because this is still a majority white country, there's been more white people who have died from COVID. If you look at it as a share of deaths, more Black people are dying, more Hispanic people are dying, more American Indian people are dying from COVID than their share of the population. That is what we mean when we say it's having a disproportionate effect on those populations is that if you just looked at the country as a whole and looked at what share of the country is Black, Hispanic, et cetera, you would not expect this many people of that ethnic background to be dying. They are because of some of the long-standing disparities in health care we have in the United States.

Brian Lehrer: Got it. We'll end with this for now. It's ironic about that finding, showing that curve, that the more Trump-voting a county you're in, the more likely you are to die from COVID. Trump hung his whole COVID response on warp speed development of vaccines. How quickly we forget. That actually happened. His base became disproportionately vaccine rejectionists. How do you explain it?

Dylan Scott: I wish there was a clean explanation. It is one of the bitterest ironies of the whole pandemic, but yes, however much credit you want to give Trump himself, like warp speed was undeniably a success. People might remember at the beginning of the pandemic where people were talking about how the fastest we've ever produced a vaccine is four years and we've ended up getting one in less than one, which is really a genuinely remarkable achievement of government resources, and science, and et cetera. At the same time, I think what set in was Trump himself, obviously from the very beginning, saw COVID as a threat to his political standing.

That's why he downplayed the threat in the first place and throughout the pandemic. Looked for every excuse to place the blame elsewhere or to continue to downplay how much of a risk COVID really played to people or possed to people. I think his base really internalized that message that they were hearing from the guy who was the leader of their whole political project. It's not that big of a deal or somebody else is to blame or there's these-- Trump, I think, also wanted to try to provide some reassurance to people, so he hyped up these treatments like hydrochloroquine to try to make people feel better.

His base heard that message, they believed it, and then there became this, I think, self-reinforcing element to it. I did a story a few months back now that frankly basically compared the psychology of anti-vaxism with the psychology of cults. This was not a comparison that I came up with, it's what happened when I called some social psychologist to say, "Hey, I'm interested in explaining the anti-vax phenomenon through that sociology, anthropology lens," and this is the comparison that they landed on.

What that really meant was, first of all, people had their own information sources. Not everybody was listening to WNYC. They've got their own internet forums, their own news outlets that are sending them very different messages from what your listeners or readers of the New York Times might be hearing. That's the first point. They just had this alternate reality that they'd constructed. Then the power, the reason that people leaned on that cult group psychology comparison was when people are in those insular in-groups, whenever they receive any conflicting information, they either try to fit it into their own preexisting narrative, or they just discard it because it doesn't fit with the story that they're telling themselves. That compulsion is really powerful. It's powerful for all of us to some degree. I think we've seen with the anti-vaccine movement how powerful it can be that despite-- I think you referenced galaxies of data that we've got that show the efficacy of vaccines and now booster shots. For those people, they don't at it that way. They see it as more proof of some one-world government conspiracy or just an example of how the media and the government will make up facts to try to convince things of people.

They take that information that seems empirical, and that seems pretty straightforward and they contort it into this narrative that they and their political movement's leaders have constructed for themselves. It's really, really hard just because of human nature, for lack of a better word, to change how people think about that kind of thing. I think, again, the resiliency of the vaccine resistance that we've seen over this last year basically has been one of the strongest proof points of the lengths people are willing to go to convince themselves that they've been right all along, rather than acknowledging that maybe they made a mistake or that the people they had trusted had misled them.

Brian Lehrer: Dylan Scott covers healthcare and other domestic policy for Vox. Dylan, good talk. Thanks a lot.

Dylan Scott: Thank you.

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. More to come.

Copyright © 2021 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.