Biden's Climate Agenda and the Obstacles Ahead

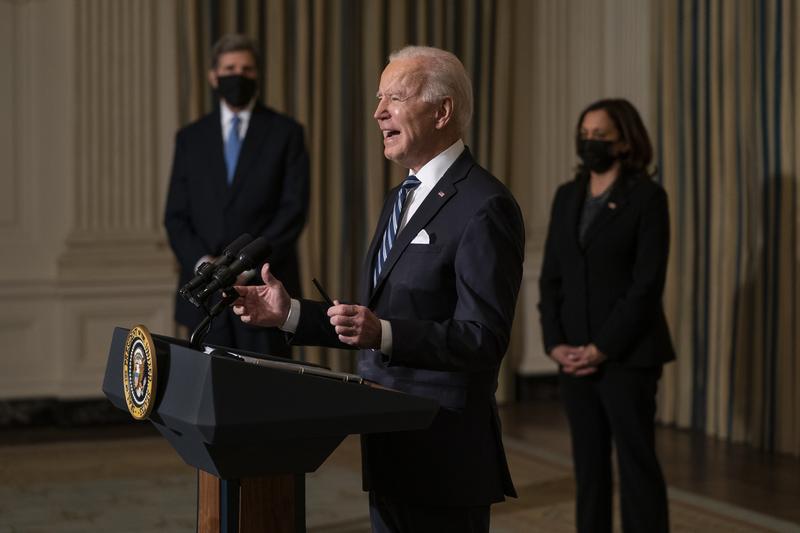

( Evan Vucci / AP Photo )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: Brian Lehrer on WNYC. By the way, one more slight clarification on the Israel Palestinian situation to be fair, is Israel is not not delivering vaccine to Palestinians who are Israeli citizens. Listener wanted me to make that correction too and that is accurate as a correction. It's not that they're just giving it to Jewish Israelis. They're giving it to all Israeli citizens, Jewish and Arab, but not in the Palestinian territory. I just want to be as accurate as we can about that.

Now, President Joe Biden has made climate change one of his four central priorities, along with the pandemic, jobs, and racial injustice. This week, Biden signed a slate of climate focused executive orders. He put a temporary moratorium on oil and gas activity in the Arctic national wildlife refuge, revoked the Keystone XL pipeline permit, set climate change as a key consideration for US national security and foreign policy, and he paused new oil and natural gas leases on public lands and in offshore waters, and he reestablished America's commitment to the Paris climate agreement.

That's a lot, and it might be driving private sector change as well. Maybe it's a coincidence but maybe it's not. Yesterday General Motors announced a goal to stop making gasoline powered cars entirely by 2035. Nonetheless, the president is going to need Congress to go much further than he can with executive orders, so let's take stock of climate policy here on Biden day 10 with Lisa Friedman, reporter at The New York Times covering climate and environmental policy. Hi, Lisa, welcome back to WNYC.

Lisa Friedman: Thanks so much for having me.

Brian: Before we get to Congress, can you take stock of these climate executive orders as a whole? How much are they just words? How much do they actually reduce greenhouse gas emissions?

Lisa: Well they're more than just words, but they don't in themselves reduce greenhouse gas emissions. On the whole this executive order, which includes dozens and dozens of executive actions, really sets the tone at the top telling, I mean, the first and biggest thing that it does, I think is tells every lever of government that climate change is going to be a priority in everything you do. One of the things that didn't get a lot of attention, because it's a task force and every president creates task forces and commissions.

One of the main task forces that this executive order can create is a national climate task force that is made up of members of every agency in the government to weave climate policy into everything they do. All the things that you mentioned, the pause on leasing, the move to get rid of fossil fuel subsidies or tax breaks for oil and gas industry, many other things in here, will ultimately perhaps lead to emissions reductions, but nothing in this executive order does the job of reducing the United States share of emissions right away.

Brian: Another executive order, Biden said Wednesday, is all about jobs, and this is related. He said his administration wants to revitalize the economies of coal, oil and gas and power plant communities, by creating jobs in those communities. To be clear, he wants to revitalize those communities, not those industries. Coal, oil and gas. Can you have it both ways? Put so many people out of work? Because it would put a lot of people out of work, right? All these things cumulatively that he wants to do, and get them retrained for green jobs at the same time?

Lisa: Yes. President Biden is walking a very interesting line here. On the one hand, they have framed the entire effort around climate change as a jobs focus. President Biden said this is climate day in the White House, which means it's jobs day in the White House. Their job is to convince states

and the people who work in these industries that they won't be hurt, they will be helped by new jobs. It's really unclear at this point.

There are commissions being set up to to address the losses in communities that are tied to fossil fuel extraction, particularly the coal industry. That is an industry that is in steep decline, whether or not there are all of these new climate orders, and that is something that a lot of people feel is long overdue and was ignored by the Trump administration in a failed effort to revive or to tell the industry that they were going to revive it, rather than help look for ways to grow new industries.

Brian: Listeners, we can take your calls with your comments on 10 days of Biden and the climate, or your questions for Lisa Friedman, who's covering that for The New York Times. (646) 435-7280 or tweet @BrianLehrer. Biden said he doesn't support the green new deal, but in response to his climate focused executive orders, Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio Cortez, who of course advocates that progressive proposal, tweeted "It's striking how much of Biden's climate executive actions reflect major elements of the green new deal, tackling climate change while addressing economic and racial injustice." Climate activists who were calling for an outright ban on fracking may have been disappointed hearing this from the president on Wednesday.

Audio clip Joe Biden: Let me be clear, and I know this always comes up. We're not going to ban fracking.

Brian: Lisa, let's take both parts of that. First on kind of the bigger observation from AOC. It's striking how much of Biden's climate executive actions reflect major elements of the green new deal, tackling climate change while addressing economic and racial justice. Even while Biden on the campaign trail had tried to distance himself from pure Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, AOC, green new deal. Where is he actually on that?

Lisa: I think if you take a close look at the executive orders and what President Biden has said and what candidate Biden said on the campaign trail, this is another area where he's trying to please many camps. There is no doubt that the phrase green new deal was deeply controversial on the campaign trail and Biden did his best to both avoid and embrace it by saying things like, "I'm not for the green new deal. I want a new green deal."

What you see in his actual plan is indeed a very strong marrying of what those who have proposed the green new deal say they fundamentally want, which is to dramatically reduce the United States share of greenhouse gas emissions, to create jobs, and to address what many on the left believe have been long time, systemic racial inequities in environmental policy. That's something we see reflected in these orders today. Does he go as far as the left really wants in other ways like the efforts to keep fossil fuels in the ground? No.

The executive orders pause leasing. They also don't end them on federal lands and waters, and they don't do anything to address the permits that may still be issued on already leased land, which is a very complicated issue, but yet one that many environmentalists have urged the Biden administration to take action on, and really put a stop to all extraction. He's not going that far.

Brian: Yes. That's an interesting one, because that executive order got a lot of attention when he said no new oil and gas leases on federal lands and that's where -

Lisa: And waters.

Brian: - and waters, and that's where a lot of the drilling gets done. In the West, the federal government owns a lot of land, and on some of that land they drill for oil and gas, a fair percentage of the oil and gas that gets produced in the United States, as well as then there are the off shore federal lands. That makes it sound like they're really going to stop, but then when you describe it in more detail, it sounds like, well, no, they're just going to not lease additional lands for that purpose, but these companies that already have the leases to drill on federal lands, which is a lot, can keep doing it.

Lisa: Look, pausing on leasing is not a small thing. It is a big deal. Currently, I believe estimates are that about half of the millions of acres already leased, companies are pretty much sitting on and not actively drilling on, but fundamentally, yes, there is a tight rope that's being walked on, on drilling. I think it's clear that particularly in these opening days, if dealing with climate change is both a carrot and stick approach, carrot being money to do research and develop and invest funding into areas that will create jobs, infrastructure, and the stick being regulations and restrictions. The Biden administration is doing both things, but trying to focus rhetorically on the carrots.

Brian: On fracking in particular, in New York state for example, Governor Cuomo has banned fracking entirely. Why would Biden not go that far at the federal level? Is it just political risk or does he see economic or even environmental pros and cons to fracking?

Lisa: Well, there's a lot of reasons. One is that it's not at all clear that a president can ban fracking nationally. A lot of fracking is done on private land. I think that's the first area, but I think this also politically goes back to this dance that we are talking about, where he is trying to, he made a big commitment to the unions. The unions backed him, not universally, but heavily in the campaign. One of the things that union leaders, particularly in places like Pennsylvania wanted to know, was that Biden as president would not ban fracking.

Union leaders have said, and they've said to me in interviews that they know a transition is happening. They're on board with that but they're worried about things happening too quickly and in a way that affects their livelihoods, which they fear a fracking ban, if something like that were to happen, would do.

Brian: Before we get off fracking to other aspects, Biden, if I'm understanding his language correctly, seems to accept the notion that there could be such a thing as clean fracking or cleaner fracking, because he had said his administration will move to implement stronger safety controls to eliminate gas and methane leaks caused by the fracking. Which is one of the big issues, which is why they consider fracking- one of the reasons that they consider fracking a contributor to global warming more than fracking was considered at first. Is there sort of a clean or cleaner fracking technology that Biden is digging in on?

Lisa: No, I think what he is-- I don't want to even start to try to get into the president's head, but what I believe that refers to are regulations around methane. The Trump administration rolled back rules around capping oil and gas leaks which produce enormous amounts of methane, a very powerful, short-term greenhouse gas that contributes mightily to climate change.

Interestingly, we have seen from many major oil companies that they are actually not opposed to regulations on methane and dealing with methane leaks. Many of them actually oppose the Trump administration's rollbacks, and that is one of the many climate change related regulations that we are likely to see reinstated and possibly strengthened.

Brian: This is WNYC FM HD [unintelligible 00:15:11] New York, WNJT FM 88.1 Trenton, WNJP 88.5 Sussex, WNJY 89.3 Netcom and WNJO 90.3 Toms River. We are New York and New Jersey public radio. We have a few minutes left with Lisa Friedman, reporter at The New York Times covering climate and environmental policy, as we take stock of the Biden presidency with respect to the climate on day 10. We'll get into what he's going to need from Congress in this area in just a second.

Listeners, I also want to tell you if you're waiting for our weekly Friday Ask The Mayor segment, it's usually now, but it's going to be at 11:30 this morning to accommodate the mayor's schedule, so Ask The Mayor coming up at 11:30. Here we go listeners, one question quiz. You ready? This is from a 2010 campaign commercial put out by a certain Democratic Senator, then a candidate for office in his state. What Senate candidate, now a Senator, from what state?

Audio clip: I sued EPA and I'll take dead aim at the cap and trade bill, because it's bad for West Virginia.

Brian: If you guessed Senator Joe Manchin, Democrat from West Virginia, you got it right. Lisa, 11 years later, he now heads the Senate energy committee, and he's one of two democratic senators, the other being Kyrsten Sinema of Arizona, who oppose eliminating the filibuster, that and key resistance from Republicans could make Biden's push to address climate at the legislative level more difficult. My question is, after all that, what does Biden want from Congress that he can't do by executive order when it comes to climate?

Lisa: That's a great question. Absolutely, if your listeners don't yet know the name of West Virginia's Joe Manchin, who once shot a hole in the climate bill in a campaign ad, that is a name that folks who care about climate change are going to be hearing a lot of in the coming year. There's a lot that President Biden can do via executive order and he started the ball on doing it, but the major emissions reductions that would come from, and this is not something that is on the table right now, but something that would come from a carbon tax or some other efforts to put a price on carbon, which is controversial in both parties, but which economists say is the fastest way to reduce emissions.

That's something that only Congress can do. Some of the big ticket items really will require Congress. A lot of his $2 trillion over four years climate plan that involves establishing 500,000 electric vehicle charging stations and retrofitting hundreds of thousands if not millions of buildings in the United States. That costs money and that's money that Congress either will or won't appropriate. There's a lot of big things that Biden will need Congress for. I think one of the most significant could be around his efforts to meet a promise he made, which was to eliminate emissions from the fossil fuel sector-- Pardon me, I misstated that. To eliminate fossil fuel emissions from the electricity sector, from our power sector, by 2035.

The Obama administration tried to do that via regulation, something that was known as the clean power plan, which was hit back and forth in the courts. The administration may go that route again, but that takes a long time. There may be an effort to seek, mandate some sort of clean energy, renewable energy standard in Congress. That will require the vote of one Joe Manchin, presumably, and it's really an open question now how far he'd be willing to go.

Brain: Can Biden make good on his promise to prioritize environmental justice, and what does that mean at the level of concrete policies?

Lisa: That's a great question. I don't think we've ever seen environmental justice elevated as much as we have. Right now this is at the level of commissions and task forces, but there are some real substantial things that are being done, including mapping to - and this is an area that I have to admit that I am not as familiar on as I should be - but mapping efforts to ensure that new policies help and don't hurt frontline communities.

This is another area where he's not just elevating it at the Environmental Protection Agency or the Council on Environmental Quality, where they have always been thoughtful about environmental justice, but in every agency. The department of energy is going to have someone focused on energy justice. I'm not sure how that will play out but it's something, again, that they are weaving into every part of the government.

Brain: All right, last question. This news about General Motors announcing that it will stop making gasoline powered cars by 2035. Assuming that that's real and assuming that that represents a reality that the whole auto industry is going to do that at the same time, because I presume General Motors wouldn't want to disadvantage themselves that much. Is that how you take it, and how much would that do in and of itself to stop global warming?

Lisa: Well, look, this is a major company that certainly sees how the wind is blowing. The Biden administration has said very openly that they intend to revive and strengthen auto emissions regulations that the Trump administration had rolled back. This commitment really takes things to another level. Ford declined to comment on GM's move, but other car companies, Daimler which makes Mercedes-Benz has said it would have electric or hybrid versions of each of its models by 2022. Volkswagen has promised more electric versions for its models. The transportation sector is a major slice of US emissions. I think that this is going to be a pretty big deal if other auto companies move in the same direction.

Brain: Lisa Friedman covers climate and other environmental policy for The New York Times. Thank you so much for all this information and analysis. We really appreciate it.

Lisa: Thanks so much for having me.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.