Biden's Climate Policies (So Far)

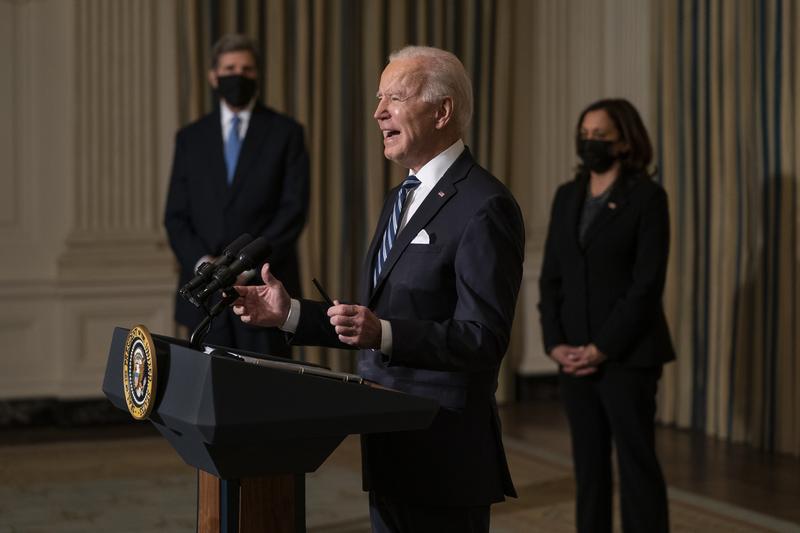

( Evan Vucci / AP Photo )

Brian Lehrer: Now our climate story of the week, and a two-parter for this Earth Day. We'll check in on the Biden administration's climate policies and put its agenda in context as efforts to bring gasoline prices down clash with long-term goals to cut emissions. They've announced some of each on these days leading up to Earth Day. On the one hand, President Biden has reversed some Trump-era environmental rollbacks, but on the other, the administration has resumed the sale of oil and gas drilling leases on federal lands.

Did you hear about that? That's a big story in the West, not so much in the East. That is a big story in the West with implications for the climate. He's tapped into the strategic oil and gas reserve, you've probably heard that one, and expanded access to ethanol-based gasoline. We'll talk about all this news with Matthew Daly, environment and energy reporter for the Associated Press focusing on climate change and policy. Then we'll talk to a leader of the activist group Extinction Rebellion, which is engaging in nonviolent civil disobedience and other forms of direct action to help force government's hand, they say.

First, Matthew Daly from The Washington Post on the Biden climate record. Hi, Matthew. Thanks for doing this. Welcome to WNYC.

Matthew: Oh, thanks for being here. I'm actually from the Associated Press, but our stories do appear in the Post and other news organizations.

Brian Lehrer: I'm sorry. I said it right the first time. I said it wrong the second time. Mathew Daly-

Matthew: That's okay.

Brian Lehrer: -from the Associated Press. I see that for Earth Day, President Biden is in Seattle to sign an order that protects old-growth forests. What do you know about that order?

Matthew: Well, it's interesting because that's been a longtime battle in the Northwest about whether to preserve these old-growth forests. They really are great at absorbing carbon dioxide and helping against climate change, but they're also valuable for their lumber. I don't know if anybody remembers the spotted owl controversy. There was a big controversy in the '90s and in the early 2000s about the spotted owl, which is a rare bird out there that they had to stop logging for a while. It's been a longtime issue.

I think this particular one is actually prompted more by California and the images that we saw of giant sequoias being burned and downed after tremendous fires after the Castle fire and other fires in recent years. They used to be considered fireproof, and with climate change that doesn't apply anymore.

Brian Lehrer: Is there a climate preservation argument that the president is making too? I remember that spotted owl and old-growth forest debate from back then that you refer to. To some degree, it was more like these are beautiful forests with these trees that have taken hundreds of years to grow to this point. We don't want to lose them for the sake of logging or other economic gain. Is there also an argument that the President is making that's, "Hey, folks, we need these trees to deal with carbon dioxide"?

Matthew: Yes. That is the main argument. The other problem though is that we have had-- I don't want to dis the whole wildfire story, but there has been a century of fire suppression. In other words when fires rage we put them out. A lot of the forests are overgrown. That just tends to fuel more fires because once the fire starts there's a lot of smaller trees and vegetation that catches fire and sets them all on fire. We've just been having tremendously more dangerous and long-term fires in California, in Oregon, and all over the West, Arizona, and New Mexico.

Brian Lehrer: There's a cycle there. Climate change makes the wildfires worse, which destroys more of the old-growth forests, which leaves us less prepared to mitigate future climate change.

Matthew: Yes. It's a vicious cycle. There's also some theory that they need to do some logging because if you do clear the smaller trees you can reduce the risk of wildfire. There's a compromise that can be made but it's a very contentious issue out there.

Brian Lehrer: Right. I remember that that's what Trump tried to blame all the wildfires on. That environmentalists didn't want to clear the forest of kindling in effect because they didn't think humans should touch nature. Maybe that is, you're saying, one contributing factor, but we can't say climate change doesn't exist as a result of that.

Matthew: Right. The thing is that we've had 20 years of drought in the West, and so that's really made it much worse. That's definitely related to climate change.

Brian Lehrer: Let's go on to another Biden policy. This week he restored a key regulatory rule that Trump rolled back under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970. This will require federal agencies to assess the climate impacts of infrastructure policy. What can you tell our listeners about this rule and what types of infrastructure projects it would apply to?

Matthew: It applies to a tremendous number of major projects, whether it's pipelines or old mines or oil wells, or even just highways and bridges. NEPA is the law, National Environmental Policy Act from 1970. It's kind of this not well-known law, but it's actually probably in the top three of environmental laws that we've ever passed in this country. It's one of the things that Trump really took aim at. He basically tried to roll it back and say that too much NEPA, which involves public comment and analysis, was making things take too long. It's slowing everything down and he wanted to speed it up.

What the White House is actually arguing is sort of counterintuitive as well. If we actually follow NEPA and do all of the regulations that we're supposed to do, that will actually speed it up because we won't face court challenges that will block the projects in court.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, if you have any comments or questions about Biden administration climate policy today on this Earth Day, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692, or tweet @BrianLehrer for Matthew Daly, environment and energy reporter for the Associated Press, not any other news organization that in error I had mentioned.

Matthew: We love them all.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] Biden restored a few different Trump-era environmental rollbacks, didn't he?

Matthew: Yes. I think one of the things that's interesting about this NEPA thing, which he did a couple of days before today, is that it comes right after the oil and gas report put out on Friday afternoon of the holiday weekend, which is generally a time when you try to downplay stories or bury them. What this did was it resumed oil and gas leasing on public lands. The counter to that is that he raised the royalty rate that energy companies have to pay from 12% basically to 18%.

It's still a betrayal, according to environmentalists, because he campaigned on ending new leasing on federal lands, and that's not what's happening. It's a big issue. It's one of those things where the president wasn't involved in publicizing it, he hasn't really talked about it, and they tried to put it out at five o'clock on a Friday, but it's still out there. That's one thing you can count on with the environmental community, is they know what's going on and they publicize it.

I think this is a particular difficult one for the president because it is a campaign promise that he's not following through on. Their explanation is, "Well, A, we're increasing the royalty rates, but B, we're under court order to do this." There are judges out there including one, a Trump-appointed judge, who said that the moratorium that Biden had imposed was illegal.

Brian Lehrer: How much leeway does Biden have to do what environmentalists want?

Matthew: Well, that's the question. They think that he still has authority. They've appealed it, so the court case is still making its way through the courts. There's that argument that he could say, "Let's wait until we figure out what's happening with the court ruling ultimately." On the other hand, Republicans have been just pounding them. They're connecting this moratorium on leasing to the high gas prices that we're all facing nationwide. In places like California, it's actually $5 or more. It's even worse on the East Coast because of refinery issues out there which are unrelated to this whole thing.

The gas prices are at the top of mind. Having a moratorium is not a good PR move for the Biden administration because even though these leases wouldn't actually produce oil for multiple years, and it's the whole long-term cycle, the immediate effect is the gas prices are up. The war in Ukraine has kind of upended Biden's whole climate agenda, and he's struggling to figure out how to respond.

Brian Lehrer: I know this is a big story in the western states where a lot of those lands are. People listening in New York and elsewhere in the east, or maybe even in California, in more urban centers and things like that, may not have any idea about these oil and gas leases on federal land. Why after all these years of fossil fuel drilling are there even still new leases to lease?

Matthew: Partly because they don't use up all the leases that they have. The oil industry is a profit-making industry, and they will try to use the most productive wells. Even if you have a lease on a well and it's not a good well, or you're not sure it's a good well, then you may not develop it. The Biden administration keep saying, "Well, you've got these 9,000 permits out there that you're not using." To which the oil industry says, "Well, they're no good. If they were good we'd use them."

There's a big long fight about it. It's sort of a proxy fight over climate change as well. How much can we do here in the United States when in fact, if you don't have oil production in the United States, maybe you're going to depend on Saudi Arabia? Maybe you're going to depend on other countries that are not as reliable. Until we reduce demand it's a difficult issue to resolve.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. I see gasoline prices are slightly lower than they were a couple of weeks ago. Is that because of Biden's tapping into the strategic oil reserve?

Matthew: On the margins it may have an effect. The phrase is that oil is a global market, which it is. He's talking about a very limited amount of oil per day. Even as a record amount of release from the strategic reserve, still when you compare it to the overall volume of world oil it's not that much. What it does is it sends a signal that maybe production will be eased, or maybe there will be some restrictions that will be eased that can let the producers produce the oil.

He's got this big short-term and long-term problem. In the short term, he wants the gas prices to come down and oil production to go up. Long term he wants to get off of oil and go to renewable energy like solar energy, wind energy, and things like that that are taking time to develop. All of those forms of energy are at record levels, but they're still lower than oil and gas.

Brian Lehrer: There was another thing that President Biden did. He waived the ethanol rule this month. Maybe you touched on that, but what makes-

Matthew: No, I did write a story about that. That's a complicated story. The idea of ethanol is that it's a biofuel, therefore it's going to help us get off of oil. There's a lot of environmentalists that don't agree with that because it's mainly corn-based and it's produced in the Midwest. What this would do would be allow a higher concentration of ethanol year-round that would allow them to have greater ethanol sales. Some of the reasons they don't do it is because there's been concerns about in the summer months that higher levels of ethanol may contribute to smog. The ethanol industry sharply disputes that, and if you write that in a story you will hear from them that they don't agree with you.

Brian Lehrer: Is it allegedly worse in a climate sense too? Because what you were just talking about is ground-level pollution that might affect people's breathing. That's not the same as climate change. I don't know. Interesting, ethanol, I mean. Then we-

Matthew: There's also an argument we produce so much corn in this country, and a lot of that now is going to fuel rather than for food. It's whether that's really helpful in terms of the amount of energy that's used to produce the corn is significant. One of those complicated issues, it's there's not like an easy it's great or it's horrible. It's a complicated issue, and it's more complicated than a lot of sound bites would have you believe.

Brian Lehrer: Because Iowa is the first state that votes traditionally in the presidential primary and caucus season, there's this parade of presidential hopefuls from both parties over time going to Iowa and basically hugging ethanol. Right?

Matthew: That's correct. It's not a politically winning position to oppose ethanol.

Brian Lehrer: Does it appear that Biden's looking for ways, politically speaking, to show he's committed to preventing climate change that aren't directly related to oil and gas, at least momentarily, while he tries to thread this needle?

Matthew: Yes. There's a bunch of evidence of that. Another story that I wrote this week was-- It kind of went under the radar, but it was a $6 billion bailout of the nuclear industry, where they announced-

Brian Lehrer: Oh, I missed that one.

Matthew: -that it's to make a pool of $6 billion available to failing nuclear plants to keep them going. The main, and pretty much only reason to do that besides jobs is because nuclear power does not produce carbon emissions. That's something that he's trying to do that surprises some people that a democratic administration is very much pronuclear.

Brian Lehrer: Yes. Climate action in Congress has been held up more than $500 billion in funding toward climate emergency measures. Some of that is supposed to be in the Build Back Better bill, other things that, of course, they can't get through the filibustering Republicans in the Senate. Where does any of that stand?

Matthew: Well, I think a lot of people would blame one man and it's not the Republicans. They would blame Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia.

Brian Lehrer: Ah, fair enough.

Matthew: You do need to acknowledge that it's because of unanimous Republican opposition makes Manchin's vote so important. Manchin actually has not really criticized some of these tax credits that they're talking about for clean energy, whether it's solar or wind or geothermal. He just wants to make sure that natural gas and other fossil fuel [inaudible 00:14:58] penalized in his point of view. He doesn't want to par. He wants to support all of them. He killed the overall package because he thought it was inflationary. It's almost $2 trillion. They've already had the rescue plan and he has a lot of concerns about that.

There's this underground effort that's going on which is keeping it quiet but talking to him. There's a lot of Democrats that are relatively optimistic that they can-- If they don't call it Build Back Better, if they call it something else, or don't even give it a name at all but just get these things done, that they can kind of go the quiet route and get it done possibly this summer. Hanging over all this is that there's likely Republicans' gains in the House at least, and probably the Senate as well, which means that they have a very limited time window if they want to get any of this done.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to talk next to an activist from the group Extinction Rebellion. Are you reporting on activists' response to the Biden administration and if they're effective or ineffective to any degree in pressuring them to take more climate-friendly action?

Matthew: No, I think they are effective. They're very visible for one thing. They represent a growing constituency, particularly among young people, that are angry about this, and that for them climate is a voting issue. For years it used to be that people said you would talk about the environment but you wouldn't vote on it. I think there's evidence that among the younger generation they are voting on climate change. If you talk to the Biden people, that climate is one of the top focus of the entire administration, and they talk about it constantly.

They're just frustrated because they can only get X amount through Congress. The infrastructure bill has actually got a lot of green-related policies. Biden will talk endlessly about the number of electric vehicle charging stations. They're doing a lot on clean water. They're doing pipes, bridges. There's a lot of good things in it from the environmental, at least, point of view, but the main thing is getting this Build Back Better production to help the renewable energy basically compete with natural gas and coal and other fossil fuels.

Brian Lehrer: Here's a tweet from a listener posting as Green new deal now, and listener rights regarding gasoline prices. "Please interview commodity traders. Oil companies trade and speculate in their own commodity and can manipulate prices because they largely control the market." Does that play into anything you know about?

Matthew: That is something that Congress is actually looking at. Senator Maria Cantwell, who's the chair of the-- she's from Washington state. She's the chair of the Senate Commerce Committee. She has been having an investigation into whether there is some middleman trading. She compares it to Enron and wants to know whether this is a similar type of thing. The Commodity Futures Trading Commission, which is not a name that trips off the tongue, but it's a federal agency that regulates this stuff, is looking into it. So far there's not been a lot of results.

Brian Lehrer: Maybe that's a topic for a future climate story of the week statement [crosstalk].

Matthew: Yes, that's a complicated one. The whole message for Biden is tough because of, as I've mentioned, the short-term, long-term. He's really got a problem with the gas prices going up because people just-- It's something that you see, it's super visible. You drive down the street, there it is in big letters, and he really wants to call-- He calls it Putin's price hike, which kind of obscures the fact that the prices were going up before the Ukraine invasion. There's just also evidence that the Russian invasion has disrupted the global markets to the extent that that's why prices are up. It's a difficult issue.

Brian Lehrer: Matthew Daly, environment and energy reporter for the Associated Press, focusing on climate change and policy as we've been assessing Biden administration climate policy today. Matthew, thank you so much. We really appreciate it.

Matthew: Oh, happy to do it, and happy to be on any time.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.