Avoiding Conflict with China

( Charles Dharapak / Associated Press )

[music]

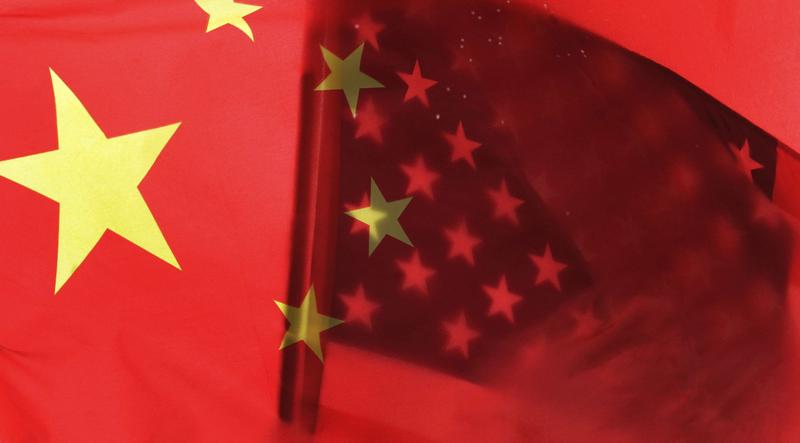

Brian Lehrer: One of the big questions around how the war on Ukraine will turn out is how much China will support Russia's invasion by staying out of the economic sanctions regime and otherwise giving Vladimir Putin its support. For example, China abstained, as some of you know, as almost every other country in the UN General Assembly, condemned the invasion in a recent vote. Well, a new book by the former prime minister of Australia, Kevin Rudd is called The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict Between the US and Xi Jinping's China.

Kevin Rudd was prime minister of Australia from 2007 to 2010 and again, for part of 2013. He is now the CEO of the Asia Society, which is based in New York and he joins us now. Prime Minister Rudd, thanks for some time today. Welcome to WNYC. I hope you can hear me okay.

Kevin Rudd: I can hear you fine. I've been enjoying the groovy music, so there you go.

Brian Lehrer: [chuckles] The groovy music over and over and over again, that same riff, ceases to be groovy after a while, but all right. Your book title there warns of a catastrophic war between the US and China, but the headlines right now, of course, are about prospects for a nuclear or other catastrophic war between the US and Russia. It's already catastrophic for the people of Ukraine. The war entered its second month today. How surprised are you, first of all, that Putin has gone as far as he has?

Kevin Rudd: I'm not surprised really, because if you have looked carefully at what Vladimir Putin has been saying domestically within Russian politics over the last several years and the last several months, in particular, he's made it plain that he doesn't regard Ukraine as a legitimate nation-state. He's made it plain he regards it as simply lost territory of Russia. Then when you mass 190,000 troops on the Ukraine-Russian border, it's usually not for a Sunday school picnic. I think this has been coming for a while. It doesn't, however, reduce the extent to which his action is shocking, brutal, and a total violation of international law and the principles of the UN Charter.

Brian Lehrer: What's at stake regarding what China does next? How consequential could China's policies be for the people of Ukraine?

Kevin Rudd: It's important to step back one bit and have a think for a moment about China's own interest with Russia before we go to what China might do on Ukraine. China, over the last 20 or 30 years, has been gradually normalizing its relationship with post-Soviet Russia. They normalized the border between the two countries. They withdrew troops facing up against each other on each side of the border and that has helped China a lot focus all of its assets on its substantive, strategic adversary in the world and that's the United States.

China is in a competition with the United States for becoming the dominant power militarily, economically, and technologically in Asia, but also globally. This has been a big national interest of Xi Jinping's China to keep that relationship with Russia going. The other factor is this, China is able to import a lot of oil and gas and agricultural commodities from Russia. By working with the Russians globally, the Russians because of their policies in the Middle East, in Syria, in North Africa, and now Ukraine, act, from Beijing's point of view, as a major strategic distraction and preoccupation for America as well.

When we ask the question, what could China therefore do in Ukraine? It's important for us to understand that China's interests are very much--

Brian Lehrer: That's your groovy music.

Kevin Rudd: It is and I'm sorry about that. It [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: That's a nice hammered dulcimer ringtone, by the way. I like it.

Kevin Rudd: [laughs] Now we're 15 all in the tennis match for groovy music. No, what I was about to say is that when we look at the question of what China can now do in Ukraine, that's the background. I think what Xi Jinping is prepared to do is limited. At present, trying to be neutral, at present, his neutrality tilting towards Moscow. It would have to be Putin doing so badly on the ground militarily that he faced imminent defeat the Chinese to step in and try and as it were at one minute to midnight, negotiate a cease-fire.

Brian Lehrer: By the way, I noticed that you gave a tennis analogy for what we're tied on. I think most Americans would give a baseball or a football analogy. I like the tennis analogy.

Kevin Rudd: I didn't use cricket, so I'm sorry about that.

Brian Lehrer: Actually, later in this conversation, I'm going to ask you an Australian Open-related question, but we'll wait for that.

Kevin Rudd: That's okay.

Brian Lehrer: We can talk long arcs of history involving Russia and China, but we can also talk about individuals. This is Vladimir Putin's war of choice because Vladimir Putin thinks it's a good idea. Other Russian leaders, everything else being equal environment, may not have made this choice. Your book isn't just about US-China relations, it's about US-Xi Jinping relations. How much do you think different plausible leaders would be making different decisions in Russia or China today regarding foreign policy, especially war policy?

Kevin Rudd: Your question is a great one because it goes to the absolute core of how much of what we are seeing at present between US and China or for that matter, US and Russia. Russia and China, is driven by structural factors, balance of power, what's in the deep national interests of each political culture on the one hand, as opposed to the discretionary decisions of individual leaders on the other.

My judgment about China is that what Xi Jinping has done since he took over the Chinese leadership in 2012/13, is he's turbocharged China's national trajectory. He's become more assertive in China's foreign policy and security policy and bringing, as it were, China into a much more confrontational position with not just other countries in Asia, but also the US and the rest of the world. It does make a difference. Doesn't explain everything, but it's a turbocharging factor.

Similarly with Putin's Russia, if Medvedev was still president of the Russian Federation, and when I was in office, I dealt primarily with Medvedev, not with Putin, this would be, I think, a different set of circumstances. Putin sees himself like Xi Jinping as "a man of history" and that means a man in the business of, as it were, restoring perceived lost territory to the national flag or the national cause. I think not being a Russia expert myself, but I think what we see with Putin's actions is a much more nationalist course about the former glories of the Russian empire than would normally have been the case in any other leader in the post '91 period in post-Soviet history

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, it's not every day we have a head of state on the show who will take call-ins, but this is one of those days with former Australian Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, now head of the Asia Society. What questions do you have for him at 212 433 WNYC, 212 433 9692, or tweet a question @BrianLehrer about today's news or his book, The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict Between the US and Xi Jinping's China, 212 433 WNYC or tweet @BrianLehrer. Mr. Rudd, what's your worst-case scenario for, as the title of your book puts it, a catastrophic conflict between the US and China? What did you write this book to try to avoid?

Kevin Rudd: The reason I wrote this book and I finished writing at the end of last year, just before Ukraine blew up, although the book deals in part with the emerging Russia-China relationship, as of that time. The reason for writing the book overall, Brian, is simply to describe the current reality of the China-US relationship. It's one of strategic competition. Whether people use that name or not to describe it, that's what's going on. China is seeking to supplant the United States as the dominant power in Asia, economically and militarily, technologically, and to do so also over time, globally. These two are in a competition for, as it were, regional and global dominance.

Washington knows that and Beijing knows that, whatever nice language may be used from time to time to describe it. My argument and why I've written the book is that either you can have unmanaged strategic competition, no rules of the road, no guardrails, which runs a daily, weekly risk of running off the railway tracks completely and producing crisis, conflict, escalation, and even war over incidents like Taiwan, the South China Sea, the East China Sea, where there are deeply unresolved territorial disputes involving China and its neighbors or the alternative, which I argue in the book, which is a form of managed strategic competition, which introduces a series of minimum guardrails, rules of the road so that we do not end up with catastrophic conflict by accident. That's the essential reason for doing the book, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Well, let me follow-up on something that you said there, that there's a competition between whether the US or China would be the dominant power in Asia. What right does the United States have to be the dominant power in Asia?

Kevin Rudd: Well, you see, this is a product of what's evolved in the period since 1945, and the position of the United States militarily and economically in East Asia has been, yes, a product of what America aspired to do after the defeat of Japan in 1945. America abandoned its historical isolationism and instead took a view that it needed to create new strategic stability in East Asia, so that it was not dominated by a rolling strategic contest between, say, the empire of Japan and what was earlier the empire of China.

The second thing is, since the war, a whole bunch of countries in the Asia Pacific region have become friends and allies and supporters of the United States, not just strategically, but also in terms of common democratic values. Post-war Japan falls in that category. They want America to remain. Post-Korean war, South Korea, exactly the same. Taiwan, of course, as a non-nation state has its own Taiwan relations Act with the United States. The Philippines is a treaty partner of the United States so is Thailand and so is Australia.

These countries, as well as a bunch of others on balance, have indicated clearly both publicly and to some extent privately, that they prefer the broad stability provided by continuing US military presence and strategic presence and economic presence rather than a whole brave new world, which would be a sinocentric world.

Brian Lehrer: Tom in Astoria, you're own WNYC with former Australia prime minister, Kevin Rudd. Hi, Tom.

Tom: Well, thank you. It's an honor to speak to a head of state. I've had this thought in my mind for over 25 years. I'm from Buffalo, an industrial city. My family became successful by all those manufacturing jobs and union jobs. My question is, how much would you agree with this? That in a sense, we gave them the future when we invested in their workforce and sent our factories over there. Thank you.

Kevin Rudd: Thanks for the question. I haven't been to Buffalo, but I gather it's not far from the Canadian border, am I right? Up that way.

Brian Lehrer: I've heard that.

Kevin Rudd: I look forward to it. I'm now living in New York. I'm looking forward to getting around the wider state of New York as well. It's good to talk to you. I think it was Tom. Is that right?

Brian Lehrer: That is correct.

Kevin Rudd: The gentleman who called.

Brian Lehrer: In Queens.

Kevin Rudd: You're right about industrial jobs. You've seen a de-industrialization of large parts of the United States. If you go to the old steel factories in Pennsylvania, that's a story writ large and not just of course in the United States, but a number of other European industrialized countries where together, the world offshored a lot of its manufacturing to China over the course of the 1990s and the 2000s and into the decade just concluded as well. They did it for a reason.

They did it because the companies concerned all concluded that they could get their product done much more cheaply there, but the result has been twofold, and you've pointed to it, Tom, the loss of critical manufacturing industries in the United States and many countries in the West, plus a whole bunch of blue-collar jobs lost as well, including in my country, Australia.

Therefore, the real question is, what then is to be done about it? I think one of the big lessons to emerge from this pandemic has been the need to rebuild a number of our national supply chains while still having the opportunity to access international supply chains, but from countries who we regard as strategically and economically reliable. I think therefore there is a way forward.

I know President Biden's talking about this a lot, which is rebuilding manufacturing and blue-collar jobs. There's a way forward to do that, but without [unintelligible 00:14:57] completely to the trade protectionism that we had in the past, so that consumers are not excessively punished with higher prices for the product that they ultimately shell out for the supermarket as well.

Brian Lehrer: Would you say one or two things that could strike that balance? Because I think what Tom raised is arguably the number one issue of the last 30 years in the United States, the hollowing out of the middle class through various forces, not just global trade, but global trade high among them and with China in particular. What would you do that is in protectionism beyond the point that you don't think it should go, but isn't anything goes, our clothes being made at slave wages in China and thinning out the American middle class from the manufacturing sector?

Kevin Rudd: I think one of the key things that we can do internationally is insist on minimum labor standards. You see, there's no point getting cheap clothes in this country, if, as you just implied in your question as the product of effectively slave labor or worse, incarcerated labor in other countries in the world. That's just wrong. Sure, that would jack up the price somewhat of imported textiles, but I think that's a necessary price to pay so that all human beings are treated with dignity.

It also gives people involved in the garment industry in this country, the United States, an opportunity to get back there and to compete. There's a second reason as well, a second thing that can be done, and that is universal environmental standards so that we're not getting product into this country, the US of A, off the back of zero environmental standards in China or elsewhere, because frankly, that just destroys the planet anyway.

These two things go someway towards writing as it were the imbalance or creating a better level playing field than before, but there's one final thing, I'd say is, if there's one lesson which comes out of the experience of the pandemic, it means that in our medical supplies industry, vaccines, pharmaceuticals, and the rest, America is a phenomenally creative, productive, and innovative country in society with some of the best corporations in the world, but all of us have had to look carefully at what we can access quickly and urgently domestically in the midst of a public health crisis.

That would give rise therefore to ensuring whatever the protectionist arguments may be, that on critical supplies for the country, particularly in medicine and pharmaceuticals, that we have secure local lines of supply and a local industry, which is servicing that both for consumers, but also producing good American jobs at the same time.

Brian Lehrer: My guest is the former Prime Minister of Australia, now CEO of the Asia Society, Kevin Rudd. He's got a new book called The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict Between the US and Xi Jinping's China. We're also talking about the catastrophic conflict ongoing in Ukraine. Rob in Nassau County has a question, I think, about, let's say, what might become a parallel invasion. Rob, you're on WNYC. Hello.

Rob: Hi, good morning, Brian, Mr. Prime minister. My question is with the aggression that we see in Ukraine from Russia, and then China basically saying that by 2050 they're going to take Taiwan one way or another, how do we square the relationship between the US, China, and Taiwan with many politicians, entertainers, athletes, executives, being afraid to even recognize Taiwan as a country or as the one China policy that we have? How do we square that relationship? How do we stand up to China to protect Taiwan when we have people who are afraid to even recognize that?

Kevin Rudd: Yes. Thanks, Rob, for your question. If I'm right about Nassau County in Long Island, am I right?

Rob: That's correct. Yes.

Kevin Rudd: I'm trying to brush up on my New York geography. I've now lived in this great city for four or five years. I'm getting around a little bit. On the question of Taiwan, which is probably the most fundamental question of all in terms of peace and war for the period ahead, my argument and I am [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: By the way, Nassau County, for your orientation, is just to the right of Queens and you can take that any way you want, but go ahead.

Kevin Rudd: I like that, and I think I understand your political reference as well. I may be Australian, but I didn't come down in the last shower of rain. On the question of Taiwan, let's think about it in these terms. I have a deep affection for Taiwan, not least because as a kid, when I was studying Chinese and finishing my university studies in Australia, I went off to Taiwan and studied there for a while as well. I've been back and forth to Taiwan many times, and it's turned itself into a robust, effective, creative, dynamic, and tolerant democracy.

China has many objections to that for the simple reason that it demonstrates that in the Chinese speaking world, you can have a democracy that works, because the Chinese historical script has been, or the Chinese communist party is, we Chinese have grown up in authoritarian political cultures, hierarchical political cultures for centuries and generations, and democracy doesn't work in the Chinese speaking world. Well, Taiwan disproves that.

On the core question of peace and war in dealing with Taiwan, here's the challenge. You see, even the Taiwanese do not themselves locally assert that they are now an independent nation. The formal position of the Taiwanese government is that they are the Republic of China on Taiwan and they are therefore contesting ultimately the legitimacy for who rules all of China. That's the current official position in Taiwan.

In terms of preventing, therefore, an armed conflict, which would cause Taiwan to fail, one of the arguments I advance in the book that I've just written entitled, The Avoidable War, is that we need time and space for the United States to rectify the military imbalance across the Taiwan straits, which has been rifting in China's direction now for the last 10 and 20 years. So much so that if there was a conflict tomorrow, most of the desktop wargaming as reported in the public media, suggests that the Chinese may well prevail.

The other thing that needs to be done apart from just rectifying the imbalance of military forces between the US and China is for the Taiwanese themselves to enhance their own national defense and national deterrence. If you've got a strong American military in East Asia, the west Pacific, and you have a strong Taiwanese national military capability of the type that we've seen with the resilience from the Ukrainian people and the military against Russia, that also creates a new and further deterrent factor.

My argument overall is, deterrence is the best way through this and there are two parts of that strategic equation. That's how militarily prepared the United States is and how military prepared Taiwan is, particularly in the domain we've seen deployed by the Ukrainians, which is what we call in the trade, asymmetric warfare. Small things against big things.

Brian Lehrer: Let me ask you a follow up question. People said Putin is in this war mostly for aggrandizement of Russia, like the Russian empire for its own sake, which might actually be the opposite of what's in Russia's economic or the Russian people's other quality of life interest. How much do you see it that way? The same question for China, how much is in the interest of the economic prosperity or general quality of life of the Chinese people with respect to Taiwan is an interest in a greater China even consistent with the interest of the Chinese people?

Kevin Rudd: On the Russia question first, even though I don't pretend to be a Russia expert, I'm a China specialist, not a Russia specialist, but looking at Vladimir Putin's public language on Ukraine for the last several years and going back to the invasion of Crimea and the Eastern part of Ukraine in the Donbas in 2014, it's quite plain that Vladimir Putin sees himself as a Russian nationalist, that he sees himself as restoring Russia's former imperial grandeur. That is a Russia which occupies territories again, that at various points, but not at all points in its history, has it occupied in the past.

It strikes me as a big animating factor, but for those of us who think it's just Putin, I think reliable opinion poll data in Russia today still suggests that he's entertaining some 60% to 70% domestic opinion poll support within Russia itself. This nationalism factor digs deep into Russian political psychology beyond the leader himself. On the China front, the other part of your question, I would argue that if you look at the texts of the Chinese communist party going back to the very beginning, that is 1949, it is part of, as it were, the communist party's religion to reunify the country, which means bringing Taiwan back into Beijing's sovereignty, political sovereignty.

If you're within the Chinese communist party and all 95 million members of it, it's an article of faith that you're going to bring Taiwan back one day and the person whose leader who brings it back then gets this position in Chinese communist party politics as near the top of the Pantheon or the communist party gods right up there with Mao. As I said before, that's been a consistent Chinese ambition since '49, but militarily, why Mao tried to do it on two or three occasions in the '50s and '60s, which we've partly all forgotten about.

We're now back into a stage where under Xi Jinping, if I look carefully at the things that he has said, he's now on a timetable somewhere between 2030 and 2050 to bring this about and given Xi Jinping's determination to remain in office, I suspect that they may seek to do so in the 2030s, by which stage he would be into his late 70s and early 80s.

Brian Lehrer: One more call for you. Sherry in Greenwich, Connecticut, you're on WNYC with Kevin Rudd, the former prime minister of Australia and author of this new book on US-China relations. Hi, Sherry.

Sherry: Hi. Thank you for this opportunity. My question is, how does the war in Ukraine and the US's reaction to it provide a playbook for China on how to conduct themselves in the future and possibly make the Chinese currency the fiat currency in East Asia.

Kevin Rudd: Well, thank you, Sherry, for that question. Once again, it's an important one because it goes to how the Chinese see Ukraine and Russia's action there as creating a series of strategic lessons for them against the time whether they choose to move militarily against Taiwan. I think there are two major impediments in China's mind right now for any decision to act unilaterally and militarily to bring back Taiwan by force to Chinese sovereignty.

The first of those impediments we touched on, and that is the view that the balance of power in the Taiwan straits at present between the US and China, between the US and Taiwan and China, while at this stage to China's advantage, is not decisively to China's advantage. In other words, there's a risk of military failure or military stalemate. The lesson of Ukraine is, however dominant militarily you may think you are, moving militarily to take and invade an entire nation state or in the case of Taiwan, an entire province, is a major undertaking.

Brian Lehrer: With the whole population of people who hate your guts for doing so.

Kevin Rudd: Yes, well, there's 25 million people in Taiwan, there's 44 million, now 40 million in Ukraine because of the refugee outpouring. If that was a land operation from two adjoining neighboring states, imagine the dimensions of the amphibious operation across the Taiwan straits. I said, I think on ABC television here in New York this morning, it would make the D-Day landings look like a cakewalk given how big it would have to be. There's one other factor and I'll touch on it very briefly because of Sherry's question about the currency.

The second thing China is concerned about is if they went ahead and did this, then they would suffer the same financial and potential economic sanctions that they've seen meted out to Russia. Therefore, the Chinese currently are dependent still on the US dollar denominated international financial system. Therefore, by the time you get to the late '20s, that's the end of this decade, will China seek to make the Chinese currency, the Renminbi, tradeable on currency markets? Will they open their capital accounts, which up until now have been closed to very tightly regulated, to give their own financial markets depth and breadth so they're no longer, in their own view, held hostage by the US dollar denominator global financial system? They're the two big impediments against China acting militarily now.

Brian Lehrer: Last question, and I warned you I was going to ask an Australian Open tennis related question.

Kevin Rudd: It's a while since I've played in the Australian Open, so this will be a good one.

Brian Lehrer: A few months at least, but it's really a COVID question. That is how you would compare Australia's COVID response and that of the US politically, or in terms of public health success. We're seeing a specific contrast recently with Australia having kicked the unvaccinated Novak Djokovic out of the country in January, rather than make an exception for him at the Australian Open where he's such a big star. Yesterday, New York City mayor, Eric Adams, specifically exempted Kyrie Irving and Aaron Judge and other New York stars who won't get vaccinated or disclose their status from the requirement for everyone else. Is that difference part of a bigger picture comparison you can make?

Kevin Rudd: One thing I've learned since living in this great country of yours and the great city of New York is not to stick my nose into your domestic politics. I'll quietly swerve around your question, but answer it in this, just talking about back home in Australia. The Djokovic decision was controversial back home and it got a whole lot of airplay around the world. Australians are a funny lot. We have a very simple attitude to life. If you've got to be vaccinated in the general community and we do have vaccine mandates in Australia, then we expect visitors to be vaccinated as well, however important they are.

In fact, the Australian psychology is a bit like this. The more important you think that you are, then the more the Australian public expects you to comply with local rules that apply to everyone else, or our equivalent of Joe Sixpack. Under the circumstances, which pertain here with your own local stars, I wouldn't dare to comment about what the mayor has done and what the context is, but Australians, we are just a difficult lot.

Brian Lehrer: There we leave it with the not difficult to have a conversation with, Kevin Rudd, former prime minister of Australia and author now of The Avoidable War: The Dangers of a Catastrophic Conflict Between the US and Xi Jinping's China. Thank you for the thoughtful conversation. We really appreciate it.

Kevin Rudd: Thanks for having me on the program. Good to talk to a local radio station here in New York, my hometown these days.

Copyright © 2022 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.