Reconciliation

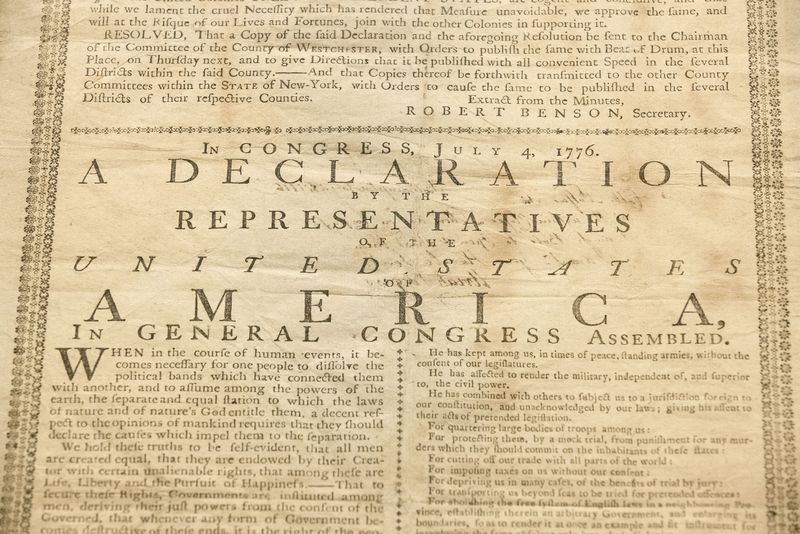

( AP Photo/Matt Rourke / Associated Press )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's the Brian Lehrer show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. This week, we've been launching our pre-election series 30 issues in 30 days, including our three nights of national call-in specials. For this morning's show, we are re-airing last night special, which was called America, Are We Ready for Truth and Reconciliation? We just did an hour on truth, now comes reconciliation, as in, how do we reconcile our debts to go forward together as one nation, closer to a level playing field? Kai Wright is my co host, it's America, are we ready for truth and reconciliation on the Brian Lehrer show, after the latest news?

[music]

From WNYC in New York, it's America, are we ready? Good evening, everyone. I'm Brian Lehrer from WNYC radio this hour, are we ready for truth and reconciliation?

Kai Wright: I'm Kai Wright, host of the WNYC podcast the United States of Anxiety. This hour will focus on the reconciliation part of that equation. The national reconciliation doesn't mean everyone smiles and all is forgiven, when you reconcile a financial statement, for instance, you determine who owes what to whom and where the money actually goes.

Brian: We want to ask, who does what to whom to approach real racial equality, real racial justice in America? In the context of the presidential race, what are the Trump and Biden approaches to looking our debts in the eye and making a larger reconciliation possible? Do they even both have any?

Kai: This is a national call-in so we invite you to suggest something. Given the history of systemic racism in this country and the massive inequalities they produce for today, how do you think we need to reconcile these accounts for a more equal future at the national level? It's a national issue, with a national historic roots, so what should the federal government do? At the presidential level, what would you like a President Biden or a second Trump administration to do? Call us at 844-745 talk? That's 844-745-8255.

Brian: Now for the sake of this conversation, we're thinking mostly about the savage and long standing economic inequalities and inequalities of power that Black Americans have had to endure, obviously, there are other kinds of inequality, but in the context of a presidential election year, do you trust either candidate to take reconciliation of debt seriously, and in case they are there people are listening, tell Donald Trump, tell Joe Biden, what do you want them to do? How do we reconcile this country's historical debts, especially economic debts, to build a more equal future, especially with respect to African-Americans 844-745 talk, 844-745-8255, 844-745 talk.

Kai: As we take your calls, we are going to be joined by Barbara Smith, who has both chronicled and participated in some of the most important moments in our country's history with racism and the fight for racial justice. She is a Black feminist scholar and co-founder of the Combahee River Collective, 2005 she was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. Barbara, thanks so much for joining us today.

Barbara Smith: Hi, how are you doing? I'm glad to be with you.

Kai: You have written two striking essays lately, first, in the Boston Globe, and then in the Nation Magazine, where you call for a martial plan for ending systemic white supremacy. You call it the Hamer Baker plan named after Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker. First off, one point you make is that people aren't even clear what these words mean, what the words systemic white supremacy means, so what do you mean by that phrase?

Barbara: I think that's a great place to start. Systemic white supremacy, is the engine that really runs much of what happens on a daily basis here in the United States, and it doesn't have malice aforethought necessarily. People hear white supremacy and they think that it refers to organized hate groups, people doing hate crime, night riders, Ku Klux Klan members, et cetera, but white supremacy is that system that does maintain a vast white wealth inequality, that does maintain redlining, whether the person who you see at the bank, where you try to get that mortgage likes people of color or not, it's just built in or baked in.

Systemic white supremacy, some people use the term systemic racism, it's those inequalities, that discrimination, that oppression, that is just so pro forma, it's really, really difficult to get to unless you have a really big initiative like a martial plan.

Kai: Why is that language important? You say it's an important thing to say systemic white supremacy and not something else, that's part of the plan, why, if some people hear it and don't know what it means, or some people hear it and it turns them off? Why do you think it's important to use those words?

Barbara: I think it's important to use the term white supremacy, because it implies, indicates that it's a system of power. When you say systemic racism, it sounds like, it's everywhere, it's big, it's happening a lot, but it doesn't necessarily immediately say to the person who hears the term, and it's enforced by a power structure. When you say white supremacy, you begin to get to that issue of differential power and why is this happening and who does it benefit?

Brian: Let's take a phone call. Here's Elle in Fayetteville, North Carolina. Hi, Elle.

Elle: Hi.

Brian: Hi, there. You're on America, Are We Ready?

Elle: Oh, hello. I would like to have my presidential candidate or my future president to talk about seriously considering reparations for people of color and Black people specifically, who built this country. I'm 27, I'm Black. My great, great, great grandmother's was a slave, and though my family has been one of the families who've pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, like people say, it's not a common thing for us, it's not as common as people would think it is, just because we have a lot of Black entertainers and stuff like that. That is not a common thing.

I wish people would get rid of the narrative that if they just work super hard, they'll be rich or they'll be as great and better off as our white counterparts when that's just simply not the case. We need additional help. It's owed to us because we built the country for it. We paid for everything.

Brian: Reparations means different things to different people, what does it mean to you?

Elle: I would like to see, for the value of what my family contribute to this country and for the people who benefited from that, I would like a $1 amount given to my family and to all the other families who have the same story, who had slaves in their families, because it gives us an opportunity to create the generational wealth that you were talking about in the first half of the show, or if we just simply feel like we are just unsafe that we just cannot be in this country anymore, because a lot of people are saying, "Go back to Africa, [unintelligible 00:08:47]."

It gives us an opportunity to say, "Okay, you don't like me, fine. Pay me what you owe me and I will gladly leave and find somewhere who will appreciate me."

Brian: Elle, thank you so much. Barbara Smith, your Hamer Baker plan, your martial plan isn't built around reparations, per se, though you're right in the nation that we could consider those as a part of it perhaps. What's the difference between what Elle is saying and what you're proposing?

Barbara: I think that reparations is so complicated in the United States for many, many reasons. I think that in order to really come up with some good solutions, that there needs to be people who have expertise and the means to analyze what would be near to fair. I don't know that it will be absolutely fair, because the person who just spoke, Elle, she knew exactly where her enslavement happened in her family. She mentioned a great great, great grandmother. I have the number of greats. I think I said the right number, but not everyone can do that. As I said, it's challenging. I believe that there has been legislation in the House of Representatives from time out of mind.

I think it was Representative John Conyers who introduced this many decades ago, to have a committee or a body of congress investigate reparations, not to give reparations willy nilly, but at least to have a governmental body to examine and investigate the issues. That's how I think that would go. I would not presume to say what the outcome would be. Sometimes people, when they talk about reparations now, they are talking about not necessarily dollars paid to individuals, but vast monetary resources poured into underserved communities. It has a lot of possibilities, but it certainly is something that should be considered.

Kai: Let's hear from Mark in Detroit. Mark, welcome to the show. Do we got you there, Mark?

Brian: Let's see if we can get Mark's line up. Mark, I think we have you now. Hi.

Kai: No.

Brian: Mark, once.

Kai: Okay.

Brian: Mark, twice. Let's try someone else. How about James in Lexington, Kentucky. You're on America, Are We Ready? Hi, James.

James: How are you today? My feeling is that we're never going to get anywhere until the government, the president's policies, or whatever else, begins to hold police officers accountable for the small things that they break within society. I mean, when was the last time you saw a police car buzz past you, past the speed of the speed limit, but you would be really freaked out if a garbage truck flew past you past the speed limit. It's the small things that lead to the culture of elitism that, "I'm allowed to do this because this is my job.

I'm putting myself on the line, and so I should be allowed to do this." It's that culture that we have to break before we can make any real change because even emails that the Louisville officer sent this week talked about being disrespected, being a warrior, and "This is what you're supposed to do to hold the line." Have people yell at you and not be able to do anything about it. That goes against everything that they were taught in the academy.

Brian: Just so everybody knows--

James: My feeling is as a police officer-- You're the government. You're preventing freedom of speech even if somebody's yelling.

Brian: Just so everybody knows what you're talking about, James. This is the email that one of the officers who was before the grand jury in the killing of Breonna Taylor sent out. An email to fellow officers, sort of saying that they believe that they did, in fact, do the moral and ethical thing that night. James, just so we're clear on what you're saying. If we still have him-- I don't think we've still got James, but Barbara, what--

Kai: I think we do, actually, but go ahead.

Brian: Oh, great. Are you saying that never mind race, it's not about race. On the issue of police accountability at least, on reconciliation around police, we do not have to talk about race. We need to just deal with this culture of impunity at the most minute level first and foremost.

James: Well, the culture of impunity because you'll notice that in most of the cases where they have a police officer up on charges and so forth, is judged against the standard of police policy rather than civil law that everybody else would be judged against. I'll give you a prime example. In Richmond, Kentucky, there's Eastern Kentucky University, and that's where they offer a law enforcement degree. That's where most of the police officers go for continuing education and so forth. On a Friday night, you're going to see everyone of those police cars blowing past regular drivers, and they're from two hours out of the district.

Brian: James, thank you very much for your contribution. This is America, Are We Ready? We'll continue in a minute.

[music]

This is America, Are we Ready? I'm Brian Lehrer from WNYC Radio with Kai Wright, host of the WNYC podcast The United States of Anxiety. We're taking your calls this hour on the national call-in that is about the reconciliation side of truth and reconciliation in this country. To achieve a true and good faith racial reckoning, what is needed to reconcile our debts? Who owns what to whom with such vast inequality still a reality in this country? 844-745-TALK. 844-745-8255. Still with us, and helping to take your calls, is scholar, writer, and activist Barbara Smith. See her recent widely-shared articles on the topic in The Boston Globe and The Nation.

Kai: Barbara, I want to get your response to the conversation we were having with James just before the break there about reconciliation on police violence. I'm thinking about Breonna Taylor, of course, and we have this news today that no officer is being indicted in her killing. In the context of your plan, of your Hamer-Baker plan, how would we reconcile what has happened to the Taylor family, and what has happened to the Black community in general over something like that in that moment? What is the step to take there?

Barbara: Well, I'm not sure this is really a Hamer-Baker plan solution, but I think that I'm just going to respond to what's happening right now without a Hamer-Baker plan being in place. I really disagreed with the last caller because it's not just about a culture of impunity, of breaking rules, and driving fast in police cars. Something happens when white officers encounter Black bodies. We have seen it all spring and all summer long. There's a way that the white mind, white culture, white system, call it structure, whatever it is, just can't quite conceptualize that Black people are valuable.

That's why the name of the movement is so brilliant, "Black Lives Matter." It had to be asserted a few years ago because the movement is now at least five or six years old. It had to be asserted because of the fact that there's no common agreement that that's the case. When we compare how white people who break the law are treated when they're apprehended versus the way that Black people who did not break any laws are treated and end up dying, we have a problem, and it has to do with race. I think about the Jacob Bell case in particular because of the fact that that police officer shot-- I said Jacob Bell.

I meant to say Jacob Blake. I'm sorry. The fact that that officer shot Jacob Blake in the back at close range seven times, and his children, his babies, are in the back of the car screaming while their father is being shot. These children were three, five, and eight years old. It's just really hard to imagine that a white police officer would peek into the back of that car, see a three, five, and eight-year-old white group of children and think, "I think I'm going to kill their daddy in front of them." It's like Tamir Rice. I mean, there's so many examples.

There's so many examples that just show that there's something operating here that doesn't just have to do with functional rule-breaking or impunity of ignoring rules because you're a cop, and you can. That's why I said at the very beginning of this period: the problem is white supremacy. Until we deal with that, we can't deal with the rest of that.

Brian: Let's try Mark in Detroit again. I think we have his line working now. Mark, we apologize for the snafu before. You're on the air.

Mark: Yes. No problem. Hello Brian, Barbara, and Kai. I'll try to make this very quick. Mark [unintelligible 00:19:10] from Detroit. I understand that right now, we're speaking about reparations. All right, to repair some injustice to a group of people, several groups, or cultures of people. That being Black and brown. My question is before we begin to look at reparations, it can't only be of monetary value. There's no more just 400 acres and a mule, and all of that. It has to be an understanding of what you're repairing. That is the actual racism that's a part of this.

My first thought would be to repair the syllabus. You have so-called "Black colleges" that don't even touch the essence of what Black is. What is the hue in human? The hue that we're referring to is melanin. We have to have an understanding of what it is that we're repairing before we get into the genetic and the hereditary racism that is attributed among Black and brown people, probably not validated people that don't even realize. They'll tell you a front door, I'm racist. I don't have a racist bone in my body yet your actions will betray a whole lot different almost inertly, almost instinctually.

It's simply from not understanding of true Black history, Black culture. The first you'd have to start with the educational portion. We started put school learning from slavery behind some 400 years, that's [unintelligible 00:20:30] what we talking about history. First, we will have to understand historical accuracy from Black and brown people. We should go four or 500,000 plus years ago, such as the judgment scene, which is a carbon dated. [unintelligible 00:20:44] live in the Vatican under lock and key by the Pope lived there for years and years of this carbon dated four to 500,000 years ago before Christianity was even thought.

Brian: Mark, I'm going to leave it there for time. Barbara Smith, anything you want to say to any piece of that?

Barbara: I think education is really important. I think that's one of the things that Mark was speaking about. I think that professor Blain also was talking about that the attacks on critical race theory on the 1619 project with the current administration in a really unprecedented way. I don't remember ever presidential administration picking out specific things that were being taught on campuses and in pre-K through 12. I don't remember that ever being singled out. We're talking about subject matter and I've never heard a presidential administration get into that, but I think it really is important that people become aware just as again as professor Blain described, people come into her classes as they have come into my classes over the years and they may have very little idea of what the subject matter is and what that history is.

I teach literature actually, but literature and history are very akin to each other, but the thing is that they come into our classes and they do leave indeed transformed. We need to have that widespread access to accurate information about the history and the culture that fills our country so that people can begin to change.

Brian: For people just joining us recently, Barbara Smith is referring to Dr. Keisha Blain from the University of Pittsburgh, who was a guest in an earlier segment on this show. Let me drill down with you then on the presidential and vice presidential candidates and how they talk very differently about systemic racism or white supremacy or white privilege. Here's president Trump from those Bob Woodward interview tapes, listen to the answer after Woodward asks him about own white privilege.

Bob Woodward: Do you have any sense that that privilege as isolated and put you in a cave to a certain extent, as it put me and I think lots of white privileged people in a cave and that we have to work our way out of it to understand the anger and the pain particularly Black people feel in this country. Do you see?

President Trump: No, You really drank the Kool-Aid, didn't you? Just listen to you, wow. No, I don't feel that all.

Brian: Believing you have white privilege is drinking the Kool-Aid and vice president Pence at the Republican Convention uses Joe Biden, stating that there is systemic racism as an accusation against Biden. Listen.

Pence: Joe Biden says that America is systemically racist and that law enforcement in America has and I quote "an implicit bias against minorities."

Brian: At the Republican Convention, by contrast, here's Kamala Harris on NPR giving one example of the consequences of one form of systemic inequality and the need for policy to intervene as she sees it.

Kamala: You can look at the issue of untreated and undiagnosed trauma. African Americans have higher rates of heart disease and high blood pressure. It is environmental. It is centuries of slavery, which was a form of violence where women were raped, where children were taken from their parents, violence associated with slavery and that there was never any real intervention to breakup what had been generations of people experiencing the highest forms of trauma and trauma undiagnosed and untreated leads to physiological outcomes.

Speaker 1: We are talking about the same thing as post-traumatic stress from a war. That's the kind of thing-

Kamala: Absolutely, unless there's intervention done, it will appear to be perhaps generational, but it's generational only because the environment has not experienced a significant enough change to reverse the symptoms. You need to put resources and direct resources, extra resources into those communities that have experienced that trauma.

Brian: Finally, after hearing the two vice presidential candidates sound so different from each other, here's Biden on a piece of systemic racism that he cites from the criminal justice system that becomes economic.

Biden: We’re also going to have to remove another piece of systemic barrier for too many Black and brown Americans. What’s holding back too many people of color from finding a good job and starting a business is a criminal record and follows them every step of the way. Getting caught for smoking marijuana when you’re young, surely shouldn’t deny you the rest of your life being able to have a good paying job, or a career, or a loan, or the ability to rent an apartment but right now that criminal record is the weight that holds back too many people of color.

Brian: We can say Barbara Smith, that people certainly have a choice this year and compare and contrast?

Barbara: I just want to get back to, 45. I usually don't call him by his name, but the fact that he said to Bob Woodward, that Bob Woodward had drank the Kool-Aid, because he actually believed that there was such a thing as white skin privilege. This is the same guy who doesn't ask God for forgiveness. It's all of [crosstalk] seems to me. Did you hear what I said?

Kai: Brian has saying he missed that one particular Trumpism that he doesn't ask God for forgiveness, but I heard what you said.

Barbara: Oh no, he was asked, this is some time ago he was asked probably doing some prayer breakfast or something like that, "Do you ever ask God to forgive you?" He said, "No, not really. I just try to do better. I just change." It was so dismissive because of course Christianity that he purports to be a member of is based upon being forgiven of misdoings and sin. As I said, same guy don't drink Kool-Aid, hasn't drank the Kool-Aid and [crosstalk] he's just impenetrable.

Kai: Listening to those tapes listening to that conversation, you’ve talked about this a little bit already in this hour, but it seems to me, one of the great unspoken truths of this is that we are not all looking for the same thing in the United States of America. That everybody is not actually the premise of this truth and reconciliation conversation we're having here is that everybody wants to tell the truth and reconcile, but that's plainly not true. In your conceiving of your Hamer-Baker plan that you said it has to be ideological as well as economics. Talk to me about that ideological piece. Where do we go from the fact that not everybody wants truth and reconciliation on race?

Barbara: I actually addressed that in the article. I talk about it several times. I say, I don't know what it will take for us to get to consensus those pieces that you played, the four candidates speaking shows how far apart people are in their points of view, they're running for the same offices, but they have polar opposite points of view about what it is. They don't even agree that there's such a thing as systemic racism. The kind of structuring of our thought processes around whether systemic oppression and systemic racism are real, that's the heavy lift of the Hamer-Baker plan.

That's really, really challenging. I don't know how we come together about this particularly given how polarized our political culture is at the present time. It's like two parallel universes that are operating in the same physical space, but other than the fact that they are the same physical space, the value system the reality checks, what we think is real, what was happening to us versus what they think is happening to us are not happening. It's very, very challenging. I think it can be done though. I do want to say that. I think it can be done.

Kai: Let's go to Muhammad in Raleigh, North Carolina. Muhammad, welcome to the show.

Muhammad: Hi, thank you very much. I'll try to be brief. I have just two points. Number one is that when we talk about reparation so this problem is an ongoing problem. When we talk about reparation and if we lets say come up with a dollar value and hypothetically we paid out, it's not the problem is not solved. It's not even half-solved because it's an ongoing thing. If we come up with a number and then let's say [unintelligible 00:30:49] out definitely somebody would say that, okay, this is done. We have solved this problem, which is not the case. That's one point that I like to mention.

My second point would be that as an engineer by profession, as a problem-solver, anytime I come up with a very unique problem, I try to see that if a similar problem has been solved by anyone else. I would like to know that if there's any research where I know this is a uniquely American problem, but still if something similar has been tried in other parts of the world successfully or unsuccessfully and if we can learn anything from it, thank you very much.

Kai: Thank you. Barbara, is there either on reparations or reconciliation or frankly on your Hamer-Baker plan, is there any preexisting example of this?

Barbara: I think that after World War II, that there was a form of reparations that were allotted to people who had been affected by the Holocaust in Germany and perhaps in other countries as well. I think that, that's an example of monetary compensation for harm done, egregious harm done, genocide and also in the United States with internment of Japanese Americans. There was also not so long ago, it took decades, but there was a small amount of reparations given compensation I don't know what term they use, but there was definitely compensation given to every person who could demonstrate and verify that they have been affected by the experience of internment as Japanese Americans, during World War II. That happened in the United States.

Brian: There's even a historical example right here in this country. This is America, Are we ready? We'll continue in a minute.

[music]

This is America, Are we ready? I'm Brian Lehrer from WNYC radio with Kai Wright, host of the WNYC podcast, the United States of Anxiety. By the way, let me recommend Kai's podcasts to you. If you are interested in the issues that we're dealing with on this program and how our country's history ties to our country's future sign up as Kai blushes in his bedroom, sign up for the United States of Anxiety wherever you get your podcasts and unsolicited plug there. We're taking your calls this hour on the national call-in about the reconciliation side of truth and reconciliation in this country to achieve a true and good faith, racial reckoning, what is needed to reconcile our debts.

Who owes what to whom with such vast inequalities, still a reality in this country to the degree that they are 56 years after the Seminole Civil Rights Act was passed. We don't even have to go down the list of wealth and income and health disparities and life expectancy and so many other things that are so persistent. How do we reconcile our national debts? 844-745-Talk, 844-745-8255. Let's go to Mark in Phoenix. Mark, you're on America, Are we ready? Hi there.

Mark: Hi there, Brian. Great program and a really important program so thank you for putting it on. I've got input on two topics that came up the first one is on the reparations. I certainly agree with systemic racism, that's just actually there that the data shows that everywhere you look for it, but I think reparations for past acts, especially historically past act is something to be very careful about because it's-- the easiest way to put it as man's inhumanity on man is legend. There really is no end to trying to undo that, after you get done with one, you go back to the Native Americans and then you go back to the subjugation of women, which is long for the Black slave trade in colonialism.

What I think as I look at the conversation, I think as you do too, you'll see that most of the issues focus around current disparities. I think that's the most fruitful place to focus because that's what needs to get corrected. I don't think there's any amount of money that would bring back an ancient family member who was enslaved but there were income gaps. There are wealth gaps and there are justice gaps that identifiable. I think if the commission or you formed a commission to focus on those gaps in groups, Blacks for now, because they're the most aggrieved, the most clearly needing reparation, but it would be if there's a wealth gap in a group of people, then allocate money to close that wealth gap.

What's the difference? Great, allocate that cash to everybody and do that on an annual or a five-year basis, after that's done and you find there are no discrepancies between Blacks and whites, great. The main thing there is focus on what the gaps are and address those because that's the real issue. The second thing was on the Black shootings and that's another one where just far too many Blacks were being shot and it's just Black and white justice for Blacks is very different than justice for whites. I would really suggest looking at a model of the FAA and the NTSB.

The NTSB investigates every single aviation or transportation crash in the United States regardless and produces a report, tries to be as subjective as possible saying here were the causes and here are things that should change in order to keep this from happening in the future. I think forming a federal organization that simply and objectively investigated every single killing by a police officer will find the most of them are probably justified. At least I certainly hope that's the case, but the investigation shouldn't be resisted by the police.

The investigation is going to find what needs to change to make sure that this doesn't happen, which generally I think everybody would agree it's not a good thing to have cops killing people, even cops don't like doing that.

Brian: Mark, thank you so much for that input. Barbara Smith, he had two big topics there. You want to comment on the first one, because it may not be the ultimate system. People could debate that, but he had a system for cash transfer over a period of five years to start to even out the bottom line so people could go forward on a more level playing field.

Barbara: We've talked a lot tonight about the issue of reparations. There's one sentence in my article about reparation. It's not a reparations plan.

Brian: [crosstalk] That's why people are trying to. It's interesting that's the word that people know.

Barbara: Yes and the thing is, I talk about such things as quality education, universal access to quality health care, housing, paid family leave, high quality child care, all kinds of things that would begin to address the great gaps that we see in the socio-economic conditions between people of color and people who are white. I think that that's just something that I really want to make sure that people understand that this is not about reparation solely and also it's not about who owes what to whom. I'm really writing about justice and justice actually benefits everyone.

If we have a just society that benefits everyone, it's not like a zero-sum, you get some and I get less. It's really about what kind of society do we want to live in.

Kai: It's interesting. Why do you think it's the case? Maybe it's about the way we frame the night, but so often when you have a conversation like this and you say, okay, let's talk about truth and reconciliation. Let's talk about thinking about how we resolve the issues it goes to people here reparations and goes to reparations. Why do you think that's the case and what does that say?

Barbara: I don't think that there's anything wrong with having that discussion. It's just that, it wasn't what I was proposing that people think about. The original Marshall plan after World War II to bring Europe back from such great devastation, economic devastation, physical infrastructure, devastation, governments disrupted because of World War II. That was not solely a reparations plan. That was like let's rebuild societies and cultures and countries that have been very much devastated by the results of major war. That's the thinking that I was trying to do, big picture thinking around a lot of issues, not just focusing on dollar amounts being transferred from one bank to another.

Kai: Let's rebuild them because it was a good idea for the world to rebuild Europe, right? That was the plan. This positive to-

Barbara: Absolutely.

Brian: Let's draw a long diagonal line from our last call, Mark in Phoenix to our next caller Jamil in Boston. Jamil you're on America, Are we ready? Hi there.

Jamil: Hello. How are you doing?

Brian: Doing all right. What would you like to add?

Jamil: Excellent. I think what we do is a lot of people are getting away from humanity. I think we need to get back to the boil down to the basics of life, where a lot of people don't understand that to solve all the outward problems, the biggest outward problems that are inside society, it has to be solved within inward first. You have to solve your problems within first and then all the outwardly problems can be resolved. I agree with Biden when he talks about the soul of American needs to be healed, you can give a person a lot of money, but if they don't have the education to use it correctly, then it can just be spent unwisely.

Now I'm African-American. I do agree with you reparation, but I know it's a very complex situation. I wouldn't even dare try to talk about it now, but historians have said that slavery was for African Americans were termed peculiar, sorry about that, peculiar slavery. It was never-

Brian: The Peculiar Institution of Slavery yes, somebody said.

Jamil: Exactly. This type of slave was never done before ever. It's almost like if I give you a vase or some people say, boss, I'd give you a vase. You go to the highest building, the potential building in the world and you throw that vase off the building. It will shatter it to millions, billions, trillions of pieces. This is what slavery has done to the African-American soul, its education nature. It's sociology. This is what happened to our dignity. Our dignity has been splatted into millions of pieces. Our health, our spiritual nature. They said during slavery that we couldn't even have businesses because we were in slavery and now you see a lot of African Americans don't even have a lot of businesses. A lot of African Americans are now suffering from the ghosts of plantation life. Now [crosstalk] is in white people.

Brian: Go ahead. What were you saying? Together finish it up. Go ahead.

Jamil: I tell many Caucasian people. I have good friends. I don't blame current Caucasian people at the bus stop or at my job or whatever, because you didn't have anything to do with slavery. You sound like a couple of Caucasian, excellent white orator on a radio station and that lady is a nice orator lady. You sound like nice people. I don't blame you. Now maybe your father's, father's, father's, father's had something to do with it. They're going to be in trouble, hot water, but you-

Brian: Jamil, I'm going to leave it there. I should say that there is one Caucasian person in this group, that's me.

Kai: I certainly suspect maybe my mother's, mother's, mother's, people were white. Certainly not as an African-American [unintelligible 00:44:16].

Brian: Nor Barbara Smith for the record.

Barbara: Yes, I'm also a Black person.

Kai: Can I just quickly put this to you Barbara, because there's something in there about this and I think we heard it in another coller too, this idea of not looking back, but looking forward and that the reconciliation is not about fussing around in history, but dealing with the right now. I wanted to get you to respond to that perspective because I hear that a lot from Black, white, all sectors of society.

Barbara: I think that the plan that I am proposing and suggesting it is forward-looking, it is from now until we get it done. It's the present and the future but in order to understand what the repercussions are, we do have to look at the past. I had never heard that statement from VP candidate Kamala Harris before, but I thought it was an excellent statement. Her talking about the generational trauma, the PTSD, that results in physical illnesses, that level of psychological trauma and stress results in physical illnesses.

You have to look at the past. If you are a doctor or a public health person, you're trying to figure out why is there so much hypertension in the Black community? You have to look at the past so it's not either or. I think that, yes, we're going to be proactive into the future so that we can get to a place of hear communal justice for people of every background. In order to understand what we need to do, we also have to look at, what happened? How did we get here? What do we do next?

Kai: In the, what do we do next? One of the things that you point out in your really thought experiment about a plan for dealing with this is that it has to be intersectional. That's another one of these words that we're now hearing in the broader conversation. What do you mean by that and why is that an important part to getting to something that is good for everybody?

Barbara: As a long time a Black feminist and also someone who has been out as a lesbian since the mid-1970s, that's quite a few decades. I have a perspective that is important to look at, not just race as a single factor, but to also look at gender, sexuality and class. My perspective about what would be an effective plan would be to take all of that into account plus more like living with disabilities, being an immigrant and having a mixed status family. All kinds of things that we would need to take into account in order to make things work.

There are people of African heritage living in the United States who don't have documents, so we need to be intersectional in how we look at what the problems that we face that we want to solve.

Kai: I'd be remissive if I didn't quickly say that as a Black gay man, who's been out since the 80s, your real writing on intersectionality was part of what shaped me. Thank you.

Barbara: That's really nice, Kai. I appreciate that.

Brian: Autumn in Brooklyn. You're on America, Are we ready? Hello Autumn.

Autumn: Hi thank you all for having this conversation and this very important moment. What I want to talk about in terms of reparation is how I see it as multifaceted that while yes, there needs to be monetary money I believe being given back to direct descendants that were in the African slave trade and brought to America. I think that there's also a need to look at how we give reparations back to Indigenous populations and getting stewardship back to them in terms of the land. I think if we look at California right now, we can see that taking stewardship away from Indigenous population there and the burning has caused massive fires that are out of control.

There's just so many facets to what we should be doing and what we could be doing. I think another side of it is in the political realm our politicians don't serve our people. They serve their big donors who keep getting them elected. There is money for them to not do what's right, is to not be passing comprehensive immigration reform, to not be passing laws that could be giving these type of reparations either monetary or programs and money piling the programs into Black and Brown communities. There's no incentive for them to do that and big money and big donors want them to not pass that type of stuff because there's money to keep people in a lower class, there's money-

Brian: Autumn, I'm going to jump in here only because the show's about to end. I want Barbara Smith to have a chance to respond to your comment at least briefly because at very least Barbara, and I know it's in your article, you do refer to Indigenous people in your pieces, that's the other massive injustice in American history. Can there be a similar plan for them or where do they come in the big picture as you see it?

Barbara: I think that the beauty of the thinking and the plan that I'm envisioning is that it is all encompassing. One of the things I say is that if we were to really fully implement the kinds of ideas and suggestions that I am proposing and it's not just me this is like the template. I'm just [laughs] like patient one or whatever. This is like has to be a big collective group of people figuring this out, but if we were to begin to do full implementation, it would mean we would have the kind of robust social safety net that would help everyone that we've never had in the nation before. Yes, it is for everyone. I also mentioned Latinx people too, it's for all of us.

Brian: Even for white people. That's another part of her Boston Globe and Nation articles worth reading about why Barbara Smith argues that everyone, including white people specifically, will have freedom from the terror and hypocrisy that poisons life on both sides of the color line, as she puts it, and so you'll have to read her Boston Globe or Nation article. to find out more about that. Barbara, thank you so, so much.

Barbara: Thank you so much, Brian and Kai.

Brian: We are out of time for this hour of America, Are We Ready? Produced by Megan Ryan, Lisa Allison, and Zach Gottehrer-Cohen. That's Jason Isaac at the audio controls, with Kai Wright host of the podcast, the United States of Anxiety, I'm Brian Lehrer. Thanks so much for listening.

Copyright © 2020 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.