After Uvalde

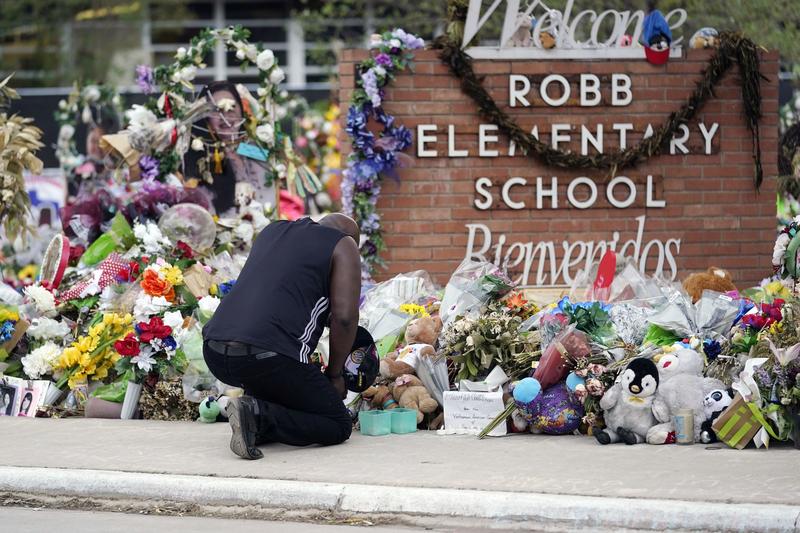

( Eric Gay / AP Images )

[music]

Brian Lehrer: It's The Brian Lehrer Show on WNYC. Good morning again, everyone. May 24th, a week ago today, is a day Uvalde, Texas will not forget because it was a year and a week ago today that 19 children and 2 teachers died after a teenager legally bought two AR-style weapons, walked into his old 4th Grade classroom at Robb Elementary School, and opened fire, as almost all of you know.

Coping and grieving with the loss of children who should have been able to go home to their parents and families that day, and of the teachers who died trying to keep them safe, parents, community members as well as children like 10-year-old Caitlyne Gonzales, push for change one year later, and though confronted with the reality of Texas gun politics, they continue pushing.

Veteran journalist Maria Hinojosa examines politics and the grief one year later in a new documentary from FRONTLINE, Futuro Media and the Texas Tribune. The documentary is After Uvalde: Guns, Grief & Texas Politics. With us now is Maria Hinojosa, founder of Futuro Media and president of Futuro Investigates, anchor and executive producer of Latino USA, and author of the book Once I Was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America, which she released in 2020.

Maybe some of you have now seen the documentary called After Uvalde: Guns, Grief & Texas Politics. It premiered on FRONTLINE last night. You can also hear it on Latino USA on WNYC 93.9 FM this Friday night at nine o'clock or Saturday at 8:00 PM on WNYC AM820. We'll talk about it now with Maria Hinojosa. Hi, Maria. Always great to have you on the show. Sorry it's about something as horrible as this, but of course, welcome back to WNYC.

Maria Hinojosa: No, thank you, Brian, and to all my fellow New Yorkers, when you read that long list of awards, and I'm like, "Yes, yes, yes." I'm just a neighbor from Harlem, and to you an old colleague, so it's good to be with my New York family. Thank you for having me.

Brian Lehrer: A neighbor from Harlem and with ties to Mexico where Uvalde is close to, and so would you remind people first who lives in Uvalde, Texas, what kind of a place it is?

Maria Hinojosa: Yes. It was a year ago exactly, around now when things became, well, somewhat clear about what had happened in Uvalde, which is an hour away from the US-Mexico border. It's a place that even though the mainstream news and the narrative is like, "Oh, my God. The border is so scary," actually Uvalde is a very calm, very South Texas, rural town where not much happens except for people driving through to and from Mexico.

What stood out was this kid from the community legally buys an assault weapon, and because he was 18, he could do that, and basically takes out his own-- Uvalde is small. Everybody knows each other. He probably had seen these kids at some point. What happened that there would be-- I'm going to go, and I'm going to go into my old 4th Grade classroom, and then that coupled with the response, rather lack of, that we became witness to 77 minutes of heavily-armed, burly, law enforcement men from Texas who were immovable for 77 minutes.

All of those things made me want to be in Uvalde, and then when I was down there, to my surprise, Brian, because I know about these thing, but I didn't remember that Uvalde and Crystal City, right next to each other, really are the birthplace of the modern Chicano, Chicana movement in the country. Uvalde has a historical importance for the entire country, for people who understand Latino and Latina history. The Chicano movement was part of the civil rights era. That's part of what we look into in the documentary as well, and I'm so pleased that people, mostly Caitlyne and her family, have let us know that we-- they're giving us a thumbs up on this documentary. That means the most to me.

Brian Lehrer: We'll play a clip here in a minute, but I'm glad you brought up that cultural and sociocultural political history because mass shootings have happened in all kinds of communities, with all kinds of victims and perpetrators in this country. Your show is Latino USA. Is there a cultural context that matters for this particular school shooting or does it so follow the pattern of what happened elsewhere with all kinds of Americans that it's not really relevant?

Maria Hinojosa: Yes and no. It is, in fact, in the most horrific way, a young man getting a hold of an assault weapon that sadly can kill this many people in a minute. That's what makes it common. What makes it uncommon is yes, this was the first time where you had a Latino kid taking out kids who looked just like him. By the way, most of those who were killed were 10 years old, 10 to 11. That is the median age of Latinos and Latinas in the United States right now, 10 and 11. People don't realize this. We are the youngest population right now in this country, and we're the second largest voting cohort.

Everything about what happens with Latinos and Latinas, particularly in the place like Texas, just immediately draws my attention. I will tell you this, when we would turn off the cameras and the microphones because we did it for television and for Latino USA, two different investigations, people would say the thing is that we also are a very divided town. They remain a divided town on the issue of race, and class, and ethnicity, but no one really wants to talk about that.

Brian Lehrer: You talk about the youth population there. One of the things I hadn't known before engaging with this documentary is that Uvalde, Texas, a city of some 15,000 people, has just one pediatrician. Really?

Maria Hinojosa: Yes. They had one psychiatrist for the whole town before the massacre. It's a small town. There's not a lot of people who are like, "Oh, yes. I think I'll just go establish my pediatric practice." Doctor Guerrero could have been based anywhere. He's from Uvalde. He's very public about being gay, and having his husband, and they run a practice there. He is the person that people trust, and as you know, he gives the most shocking testimony in our documentary. It is shocking, and I think that's why people are focusing on him. Also, because he's just such a huggable guy. You all wish we had that guy as our pediatrician.

Brian Lehrer: There's a whole other documentary that could be done, therefore, on the dysfunction of our healthcare system, and how it does not distribute pediatricians and other doctors evenly across populations-

Maria Hinojosa: Correct.

Brian Lehrer: -with the finances of healthcare in this country being what they are, but that is a different documentary. Do you want to talk about any of the victims? I know one of the things that we all try to make sure to do, as responsible journalists, and you definitely do it here, is not just focus on the perpetrators, not just give the people who commit mass shootings all the attention, but also some of the people who died or some of the people who are in grief. Do you want to tell any particular story or two as representative?

Maria Hinojosa: Brian, after September 11th when I was at CNN, and we had to make those phone calls, and many people wanted to talk about their loved ones who were lost on September 11th. For me, approaching Uvalde from the outside, I wanted to be very sensitive. I did not want to be like a journalist who's like, "You lost your child. Talk to me," like that. We actually focused on Caitlyne because she's a survivor, and because she's taken this activist perspective.

She's turned this tragedy into her becoming a full-blown activist at 11 years old right now. What was shocking to me, Brian, was hearing from people, because I was like, "I want to be respectful of the families," and they were like, "The families feel ignored. They don't feel heard." The families have heard people say to them, "Can you guys just move on." I was like, [Spanish language] This was shocking to me.

We did meet the families, but the story that we tell is focused on Caitlyne Gonzales. Anybody who looks at The New York Times, they did something extraordinary on the one-year anniversary of Uvalde, which is why this massacre, I hate to say, cuts differently. Above the fold, more than half of the page, was Caitlyne Gonzales dancing on a cemetery plot for her very best friend, Jackie Cazares. Uvalde is transforming the mourning into, in this case the cemetery is beautiful, gorgeous, it's where people have breakfast with their kid. They may have lunch with their child. Many of the plots have benches. They just go and sit at any time of the day, any day of the week. The Mexican Uvalde cemetery is full of life. That is part of, I think, what cuts differently about Uvalde.

I know this is going to be like, this has nothing to do with Frontline and an investigative journalist, I'm just going to be Maria Hinojosa here from Harlem. I learned this actually after September 11th. The families taught me, if you are open, you will feel them present. I felt these 19 little angels and two adults present with us as we made this film, accompanying us, because you know, Brian, getting a Frontline done, period, and getting a Frontline done in basically five months, almost impossible. That's what we did. I believe that the little angels have been with us.

Brian Lehrer: Let me play a clip for our listeners from the documentary of Caitlyne Gonzales's best friend, Jackie Cazares' parents, Gloria and Javier Cazares. Here we go.

Speaker 3: We're not trying to take anybody's guns away.

Gloria Cazares: It's just gone on for so long that we have to meet somewhere in the middle, and how is raising the age not in the middle?

Javier Cazares: I'm a gun owner. I can still carry. We just want to make this a better, and safer place [unintelligible 00:11:30] anymore, but somebody else's child.

Brian Lehrer: I don't even know what the question is. What's it like for people like Gloria and Javier and Caitlyne, I guess not to be just in grief, but to be pushing for change, Maria?

Maria Hinojosa: Well, what Caitlyne's mom, Gladys, said to us is we should all be in mourning. We should be spending this year in mourning. Instead, we're having to spend this year demanding accountability. Because Uvalde may not be front and center in our minds here in New York City, but the families have not been given any information regarding the investigation. As The Washington Post reported on the one-year anniversary, there has been no accountability in terms-- Pete Arredondo was fired, but besides that, what about all of these law enforcement officers who broke protocol and did not, frankly, as Caitlyne Gonzalez says, do their job.

It's a very shocking thing, because the Hollywood narrative on law and order, which we all love, and what we witnessed here on September 11th, is that our law enforcement and our firefighters went in. That's what we experienced. They went in. In Uvalde, they stopped in their tracks when they realized that it was an assault weapon, because as we documented in our documentary, they say whoever went in first was going to be taken out. You can't really investigate your way out of the fear of man. There's no way that you can data crunch it and investigate, because how can you do that?

I think we have to talk about the elephant in the room, which is that yes, they were absolutely terrified of that assault weapon, which is strange that law enforcement is like, "Legalize, make them available to 18-year-olds," because it's like, well, those are the weapons that have the bullets that will shoot through your police armor. I don't understand this picture.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, anybody out there right now who saw the Frontline documentary last night by Maria Hinojosa or who wants to call in with anything regarding the one-year anniversary of the school shooting in Uvalde, Texas, 212-433-WNYC, 212-433-9692. Is it your understanding on what you just said, Maria, that law enforcement members generally are so pro-Second Amendment that they are for widespread distribution of AR-15s, even though it leaves them outgunned in situations like this, even though it was the nature of these military-style weapons that was a factor in deterring the police from going in and doing their jobs on that day?

Maria Hinojosa: Brian, I don't understand it. I've spent basically, since January, back and forth from Texas, from Uvalde, from Austin, and I cannot wrap my head around this. I don't understand why more of our colleagues are not putting this on the front page, which is, "Just so we're clear, y'all want to make assault weapons available including to 18-year-olds." We need to be clear, the assault weapon will take out the police because it will shoot through their regular police armor.

The only way you're not killed by an AR, and this is stretching it, is that if you have war armor, and you have war shields. That's where we're going? It just doesn't make sense. We interviewed a representative from Gun Owners of America and really trying to understand that side and what their answer is, "Arm teachers with assault weapons in the classrooms." You just wish that there was more, but that's where they're at. Take the law into your own hands, have teachers armed.

Brian Lehrer: Here's another short clip from the documentary. This is from the part where you're speaking with Texas Tribune reporter Zach Despart, who reviewed hours of footage from that day.

Zach Despart: Most, if not all of the killing, took place before police had the opportunity to intervene, but there's a lot of evidence that builds throughout this time, that yes, there are students and teachers in the classroom, that some of them have been shot, and that some of them need immediate medical attention. Even when more reliable information is coming out about the seriousness of the situation, that information is not flowing well on police, but they are well aware that these type of rounds, because of their high velocity, will penetrate their normal body armor.

Brian Lehrer: You want to just expound on that clip, Maria?

Maria Hinojosa: There was a time when then President Bill Clinton banned assault weapons across our country in the '90s. That lasted for a decade till 2004. Then assault weapons were made legal again and accessible. I think it is a very difficult conversation. I beg forgiveness for anyone who has had to go through this, but the other thing that we touched on in the documentary is talking with the pediatrician, Dr. Roy Guerrero, about what he saw. This is for those of you who have watched the movie Till, which by the way, is a beautiful and powerful movie documenting American history, it was the decision of Emmett Till's mom to open the coffin.

I'm just saying what I saw, Brian. I'm deep in conversations with my therapist now because I'm finally done traveling, and she's insisting that I have to talk about what I saw because I was privy to things, and I don't want to. At the same time, my immediate reaction after some of the things that I saw was like this needs to be-- I'm sorry, again, I apologize. My human reaction was like, "If everybody saw this, there would be an uprising of people saying [Spanish language], take these things away." That's what Dr. Guerrero says. I'm sorry, again, a trigger warning, but he says, "You're going to look at a decapitated child, what more is there to say? That you have to identify your child by what they were wearing."

This is the horror. It is the place where we are at in this country, because we all saw the images of Hollywood, Florida, where again, those were shocking images, and the media decided to show them. It's like, this is what it looks like. I don't believe that our country is entirely desensitized. Again, to Emmett Till, men, Black men, Mexican men, Chinese men, Indigenous men were being lynched. People would go to see the lynchings and send postcards. Yet, after Emmett Till's mother makes that decision, history changes. Where are we in the place of American history of realizing that guns are the number one killer of children in our country?

My children are grown now, but soon I'll be in a place where I'm like, "Oh my God, it's my grandkids." I think that we are coming to some-- I don't know, but I'm feeling like there's a bit of a turning point. By the way, let us not forget that today, one year ago, it was the Buffalo massacre, where we at Futuro Media lost somebody very close to us at the Buffalo massacre, which was a racist massacre. Here we are, Brian. I just never thought that I would be a journalist doing this kind of work on this issue right now, but after the families of Uvalde, I'm more committed than ever.

Brian Lehrer: I hate to reinforce one of the darkest parts of what you were just saying, but one of my colleagues just sent me a note, a colleague who is a parent of young children, that because of incidents like these and the frequency of school shootings in the United States these days, that parents are now being trained to remember what clothes they send their kids to school in.

Maria Hinojosa: Oh my God, no. Oh my God. See, [Spanish language] I just think our country, this is where you're like, "What is going on with the United States of America? How is that happening? I don't understand." This is my personal feeling. The documentary, the research that we did, the investigation that we did, the data that we show actually is that the majority of Texans are good with raising the age of legal purchase of an assault weapon from 18 to 21.

I do believe, as I said in Binghamton yesterday morning, I actually think our country is cooler than we think, but the power of the narrative of we have to have access to weapons to defend ourselves from the federal government, which is-- I know I just threw that at people, but in Texas, that is part of the ethos. You arm yourself, this is what we heard from the representative of Gun Owners of America. You have to arm yourself because you never know when the federal government is going to take over. It's just like, "Whoa."

It's approaching this conversation where we are so far apart, yet I believe that the majority of Americans really want to handle the issue that guns have become the number one killer of our kids in this country. [Spanish language] In the world's leading country, modern, et cetera, et cetera, then no, it's not true. We're not a leader.

Brian Lehrer: Rick in White Plains, you are on WNYC with Maria Hinojosa. Hi, Rick.

Rick: Hey, Maria. Both sides are misinformed. Both sides are exaggerating. I have to say this, I've spent over 30 years in the criminal justice system. The easiest gun to shoot out there, one of the easiest guns is the AR-15. That's why maniacs pick it. However, any hunting rifle, including hunting rifles you can buy in Canada and in other countries, will go right through both sides of a bulletproof vest. You'll get the gun enthusiast saying, "Listen, this is just a gun like any other." No, it's not. It's extremely easy to use. However, part of the issue, and this is the thing. If you go around trying to define what an assault weapon is, if you go up to West Point, it says it's a select-fire weapon that can be fired while walking.

That's what the US Army's definition is if you go to the gun museum in West Point. None of these are machine guns. The definitions have to get straightened out. I don't have any issue either with raising the age to 21, but here's the problem, you've got extreme people on both sides and a lot of the issues aren't being talked about. One of the most important ones is that the HIPAA laws right now prevent people in law enforcement from knowing who shouldn't get a firearm.

There are people out there who are on all kinds of psychoactive medications. Not only should they not be driving a car, which they certainly shouldn't be doing, but the media doesn't report when somebody who's on psychoactive medications takes an SUV and kills five or six people.

Brian Lehrer: Rick, let me follow up on one thing that you said about the AR-15 and hunting rifles. My understanding, and I'm no expert, is that the AR class of weapons does fire more bullets more quickly, therefore, it can do more damage to more people than something like a conventional hunting rifle or a pistol. Are you saying that's wrong?

Rick: No, I am saying it's wrong. If you take a standard pump, 12-gauge shotgun, you can buy in New York City tomorrow, and you put four rounds of 12 gauge magnum in it, each one of those rounds hold 16 32 caliber bullets. 16x4, as fast as you can pump that shotgun, you can get lead flying out as fast as an AR-15. The difference is it's difficult to use a 12-gauge shotgun.

Brian Lehrer: Rick, I'm going to leave it there for time, but thank you for everything you put on the table.

Maria Hinojosa: Here's the problem that I have, Brian.

Brian Lehrer: Go ahead.

Maria Hinojosa: Thank you, Rick, for your call. I think there's a particularity, and by the way, some of the people who I interviewed who are doing security at the Capitol say, "Raise the age to 35." When you're like, "Well, you could kill this many people with the same amount." The gun owner of America said, "Well, you could drive a truck into a classroom." It's like, "What are you talking about? We cannot go down that route of, "Well, what about this?" This is a weapon of war. You're exactly right, Brian. It is that because it will kill, and I hate to say this, efficiently, which is why it is, as we said in the Frontline, the weapon of choice for mass shooters from people who want to commit a massacre. I'm sorry to say that the-- if not all of the death in Uvalde occurred in the first minute. We have to wrap our head [crosstalk]

Brian Lehrer: The bullets, from what I've read, also do more damage.

Maria Hinojosa: [Spanish language] That's the thing. You cannot survive. You cannot survive getting shot with an AR.

Brian Lehrer: We're going to have to leave it here for now. Listeners, Maria Hinojosa has done it again.

Maria Hinojosa: Hold on, Brian, hold on, hold on. I just need to say because I can't leave it there. I cannot leave it with-- we're talking about guns. I want people to understand that in the process, there's a saying in Spanish from Mexico, [Spanish language] there is no bad from which good cannot come, and something is happening in Uvalde that is different. That is what I want to focus on. I want to focus on the fact that the kids and the adults in Uvalde are trying to come to terms with this by becoming part of a democratic process, by owning their voice and their agency to demand answers and to demand from their local Texas government, action.

That to me is the story of Uvalde. Yes, we will never forget, and by the way, look at the murals. We're about to drop an additional piece just about the murals because there is tremendous beauty in Uvalde. We're far from Uvalde, New Yorkers, but you can also go and look at the murals and become part of the healing and the learning of the story. Brian, I'm so thankful that you gave us this time to talk about the documentary and I hope people will watch and I hope they'll engage and let us know what you think. Again, Brian, so thankful to be on with you talking about this.

Brian Lehrer: Listeners, you can hear the Latino USA radio version here on 93.9 FM Friday night at nine o'clock, here on AM820 WNYC, Saturday night at eight o'clock. It originally aired on the TV version on Frontline last night. Can people still see the video?

Maria Hinojosa: Yes, yes, yes, yes. The video is up. You can watch it on demand on YouTube or at pbs.org/frontline. Just check out our Futuro Investigates or my handles because we're dropping-- I have a piece dropping actually, a written piece that I don't know what the final title has been, but where I basically challenge the narrative of the all-powerful Texas law enforcement man who is afraid of nothing because I think we all saw, well, actually, no, they are afraid, and so we just need to talk about that elephant in the room. That will be published sometime this week on our site at Futuro Investigates and Futuro Media. I hope people will engage with that.

Brian Lehrer: Maria, thanks.

Maria Hinojosa: Thank you.

Copyright © 2023 New York Public Radio. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use at www.wnyc.org for further information.

New York Public Radio transcripts are created on a rush deadline, often by contractors. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of New York Public Radio’s programming is the audio record.